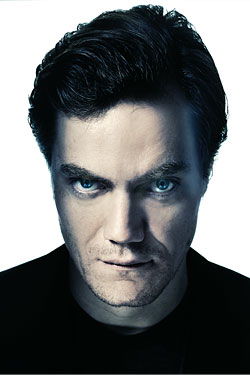

In every role, Michael Shannon makes you wonder, makes you want to know, what the hell is eating him. That magnetism has worked in his favor onstage and onscreen in Tracy Letts’s Bug, in which something supernaturally insectile possibly was eating his (Desert Storm vet) character, and works again, like gangbusters, in Revolutionary Road. Sam Mendes’s film of Richard Yates’s 1961 novel gives Shannon his breakout role: John Givings, a hyperobservant head-case (veteran of 27 electroshock treatments) whose bitter insights shatter the fragile harmony of fifties suburbanites Frank and April Wheeler (Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet). At six foot four, the actor is physically threatening. He lurches, his center of gravity off, and with his overhanging brow, his brood-and-blurt delivery suggests a caveman forced to snatch at his own darting thoughts. Both his scenes are showstoppers, outlandishly funny yet redolent of doom: It’s John who finally tears this couple’s playhouse down.

Over lunch in Carroll Gardens, near his Red Hook apartment, Shannon recalls how badly he’d wanted the part. In his audition, he explains, he pulled out every stop when it was time to tell his controlling mother (played onscreen by Kathy Bates and in the audition room by the casting director) to shut up. When it was over, she told him that in all her years in the business, she’d never felt so personally wounded by an actor’s reading.

He thinks a moment. “I guess for years and years, I’ve been wanting to tell my mother to shut up, and I finally got an opportunity to do it. One of the great things about acting is you can do things that in real life would get you in trouble. I think that’s something I figured out pretty early on. ’Cause I had some issues … ”

Those issues began 34 years ago in Kentucky, where Shannon was born to parents who split up soon after. (They’ve each been married five times.) He moved back and forth between Lexington and Chicago, where his father was an accounting professor at DePaul, and dreamed of being an architect or playing jazz. He only started acting to get out of sports. (His growth spurt didn’t come until his junior year of high school.) His father and stepmother sent him to a therapist: “I just sat there and stared at him, and eventually I got up and threw all the books off his shelves and knocked over a lamp and walked out of the room. But now we’re best friends. If you give me enough time, enough leash, I can become pretty reasonable.”

He fled school and acted in his first professional play at 16, and he can recite his first review: “ ‘Michael Shannon is a semi-attractive youngster who thinks acting is flapping his arms like a bird and rubbing his eyebrows.’ ”

Well, at least the critic was specific.

“Yeah, he was. He was very specific. Yeah. The next night, I taped my arms to my sides.”

He did have a lot to learn. “I had no form,” he says. “I had no technique. I just had this passion that was unextinguishable. I read that review and I kept doing the play. And the next play that same critic came back and said, ‘I still maintain that Shannon has technical deficiencies, but I guess he is pretty compelling, at the end of the day.’ ”

That next play was Fun and Nobody, with director Dexter Bullard and Tracy Letts, then a full-time actor. “He was obviously very raw,” recalls Letts, who most recently won a Pulitzer for August: Osage County. “He was estranged from his family and was maybe spending some nights in the park. He seemed to be at loose ends in his life, and he just threw all his psychic energy into this role. And you couldn’t take your eyes off him.”

Letts remembers that Shannon asked why the fight scenes had to be choreographed. “He didn’t know why we couldn’t really fight,” says Letts. Years later, it was the fighting in Letts’s Killer Joe that Shannon says turned him from an awkward kid into an actor: “You had to be able to command your body or else you’d get hurt or you’d hurt somebody else.”

For Letts, Killer Joe was also the Great Leap Forward. “Watching Michael in ’98 in New York was the first moment it was no longer watching a dog onstage … which is kinda what it felt like earlier, just riveting. You can’t take your eyes off a dog onstage, but a dog doesn’t necessarily help you tell your stories. I remember thinking, ‘I can’t do what he’s doing right now. I don’t know how to do that, he’s so good.’ ”

But for all the craft he’s cultivated, there’s still something feral. His friend and fellow actor Amy Ryan says, “He’s one of those actors you swear is not an actor. You hold your breath ’cause you feel he’s a real person and you’re spying on him.”

After many years in Chicago and two in L.A. (he was in three Jerry Bruckheimer films), Shannon now lives here with his girlfriend, Steppenwolf ensemble actress Kate Arrington, and their 6-month-old daughter. (“I have issues with the marriage thing. But I’m super in love with this woman, so I’ll probably get over it.”) He’s working a lot: His other great role in 2008 was the lead in the haunting Arkansas revenge drama Shotgun Stories, in which he’s relatively subdued (relatively—inside, his character is roiling, at a loss to express his anguish over a father’s abandonment). In just the past year, he’s appeared in Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (Philip Seymour Hoffman killed him), the Off Broadway play The Little Flower of East Orange (Philip Seymour Hoffman directed him), and Craig Wright’s Lady (also Off Broadway). He was supposed to be in Letts’s August: Osage County but dropped out to do Revolutionary Road. Shannon had been in Letts’s other plays, and the writer worried that he was losing his good-luck charm. They laugh about that now.

At lunch, Shannon is very smart and hugely likable, but his easygoingness seems just a mite practiced. The danger is still palpable. Ryan goes on strolls with him and sees people cross the street because “he’s such an intimidating character. He can break your heart and at the same time scare the shit out of you.” Noah Buschel cast him as a stuporous, alcoholic private investigator—the world’s least inconspicuous tail—in the delightfully strange noir The Missing Person (it premieres at Sundance), and says he has heard the actor compared to both DiCaprio and Richard Kiel, who played Jaws in the James Bond films. There’s a bit of both. “He looks like an eccentric slacker who just rolled out of bed,” Buschel says, “but he sees every fly in the room.” Some damaged people are like that.

Shannon wants to keep doing theater—new plays, he says, not chestnuts like A Streetcar Named Desire or True West. He’ll soon head off with Werner Herzog to shoot a movie in Peru, the site of a legendary psychodrama between that German director and his incorrigibly mad leading man, Klaus Kinski. But Shannon promises he has his own madness on a leash. “You have a lot of wind inside you,” he says, “and acting is the kite.”