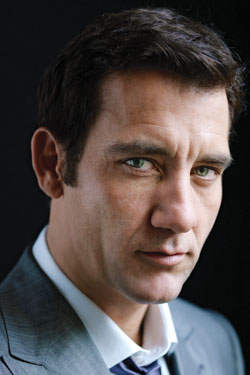

For years, Hollywood has been trying to warn us. From Die Hard to Austin Powers, from Spider-Man to Iron Man, nearly every blockbuster has screamed Evil corporations are gonna destroy you! But did you listen? No. And look what happened. Maybe now you’ll take Clive Owen’s new thriller about a corrupt bank a little more seriously.

“It’s a genre movie, but it also questions whether banks are using people’s money appropriately,” says Owen of The International. “Are these sound institutions? We’re all asking that right now.”

At the Berlin Film Festival last week, festival head Dieter Kosslick said the film was selected months ago but has gone from being a fun action flick to “practically becoming a documentary.” Let’s just say the film is prescient, since it bears little resemblance to reality, playing like a classic populist revenge fantasy, with Owen as the Everyman hero—an angry, obsessive investigator who teams up with a Manhattan assistant D.A. (Naomi Watts) to take down the bad guys.

Owen belongs to a small clique of rugged actors who can walk the narrow line between too handsome (Brad Pitt) and just plain rough (Ray Winstone), allowing them to masquerade as Everymen while still hawking BMWs in Armani suits or pitching men’s cosmetics (Owen is the face of Lancôme’s Hypnôse Homme cologne and anti-aging skin-care line). Much like fellow Brit Daniel Craig, or this country’s Matt Damon (at least since he assumed the role of Jason Bourne), Owen is a hunk with zero pretensions.

“That’s what’s so great about him,” says Naomi Watts, his co-star in The International. “He’s got this movie-star quality, but he’s not too cool or too sexy or too good-looking—I mean, what am I saying? Sorry, I’ve been breast-feeding. I call it my lactose lobotomy,” says Watts with a laugh. “Of course he’s incredibly good-looking! But you can see the flaws, as well, that make him human. When you act with him, he’s just there, seamless, oozing truth.”

“He can look that good and still be me and you,” agrees Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run), the film’s director. “He’s able to be that common man—and if you combine that with his very impressive physical presence, kind of like Robert Redford, that makes him unique as a star.”

And he owes it all to … stubble. A working-class kid from the English Midlands, Owen broke out back home as clean-shaven man-bait on the TV series Chancer. Fresh-faced and dapper in 1998’s critical hit Croupier, Owen was almost distractingly gorgeous, and he seems to have understood this. Since 2001, when he crossed the pond as the smoldering valet in Robert Altman’s Gosford Park, Owen has been cultivating his stubble, and doing (almost) everything he can to shake off the pretty-boy mantle. Indeed, except in product endorsements (as if a close shave is his way of separating art from commerce), Owen’s facial hair has grown heavier and his costumes more sordid in almost every film. He barely seemed to have bathed in King Arthur. And in Children of Men, he tried to convince director Alfonso Cuarón to let him wear chunky, ugly glasses—until the women on set successfully lobbied to uncover his green eyes. “I’m not interested in vanity,” says Owen with practiced finality.

In The International, the actor spends so much of the film getting banged up and thwacked that by the end, his face is a mass of scabs and scars. He doesn’t so much win as survive in three elaborate action scenes: one across the rooftops of Turkey, another through the streets of Berlin, and a third in New York’s Guggenheim Museum.

“Tom and I were doing the first walk-through of the museum after-hours,” says Owen, “and an attendant said to us, ‘It’s about time we had a shoot-out at the Guggenheim.’ But our feeling was that if you’re going to do a gunfight in the Guggenheim, you’d better bloody well do it right. You can’t just shoot shit up.” (And Owen already did that in Shoot ’Em Up.) The result (see below) is a choreographed, De Palma–style set piece that the actor, predictably, turns into a bloody mess. “I could have played it cool with the gun, and looked good,” says Owen. “But this guy is really terrified. If I was suddenly in a gunfight—I’d shit my pants!” (Thankfully, we are spared this lack of vanity.)

Owen’s next film, Tony Gilroy’s Duplicity, is a corporate-insider thriller, too, albeit a shade more escapist, reteaming Owen with pal Julia Roberts for the first time since he told her to “fuck off and die” in Closer. “I get approached all the time about that one,” says Owen. “Julia told me, ‘If we could do a whole movie where you just lay into me, it would make $100 million.’”

As corporate-security experts who decide to fleece their firms, Roberts and Owen engage in an escalating war of vicious zingers. “It’s almost as brutal as Closer, but more fun,” he says. Like how? “Let’s see, I think the best I give her is … now, let me see—it’s important I get this right: ‘Maybe you’re so used to having your legs in the air you don’t realize it, but you’re upside-down, sister, I own you.’” Does she give it back? “Oh, she gets me good.”

Process: Shoot-out at the Guggenheim

The Goal

The stunning sequence pits Owen against a mob of gunmen. Tykwer was going for a set piece “at once orchestrated and experimental.”

The Challenge

Tykwer shot exteriors at the Guggenheim but couldn’t close the museum long enough to shoot the action, which was to take six weeks.

The Set

So the director created a life-size replica of the interior of the iconic building—built in two halves over sixteen weeks—in an empty Berlin railway roundhouse.

The Action

The fight rages for fourteen minutes. “The spiral exerts a vertigo effect on everyone,” says Tykwer, and amplifies the disorientation of Owen’s character.