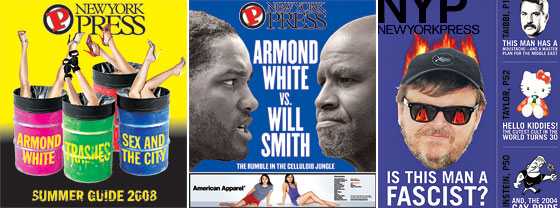

With the commencement of the 75th-anniversary year of the New York Film Critics Circle, Armond White, the newly elected chairman, passed the first morning of what he called “my reign” recounting how he’d barely made it through the 74th season, which had ended the previous night with the traditional awards dinner. For starters, White, whose writings can be found in the downtown freebie New York Press, was appalled by the behavior of the stars, particularly Sean Penn and Josh Brolin, who acted like “bores, or boors, or boars, however you want to spell it.”

Also irksome, if not unexpected, were the circle’s selections for the best films of 2008. The procession of wrongheadedness began with the Best Cinematographer award for Slumdog Millionaire, a film whose cresting hype machine had failed to fool White, who saw the picture for what it was, i.e., a “TV-slick fraud” full of “blithe condescension.” No more worthy was the nearly universally acclaimed Romanian movie 4 Months 3 Weeks and 2 Days, chosen as the Best Foreign Film despite White’s contention that it was nothing more than “a fad based on liberal self-reproach; a hangover from what Susan Sontag criticized as Americans’ ‘triumphalist national self-regard.’ ” Also unsurprising was the Best Picture anointment of the relentlessly middlebrow Milk when it was clear as day that the film was little more than a “silly …celebration of an ambitious pol.” Even the widely beloved Wall-E, the Best Animated Film, was damned by the new chairman, who said it smacked of “ugly, end-of-history cynicism.”

Lest anyone think White is reflexively negative, the critic says he has never knocked a film without suggesting a superior movie a viewer might more profitably spend his time watching. Instead of the usual ten-best list, White offers the “Better-Than List,” in which he expounds on why one lesser-known or critically unfashionable movie is better than another highly touted but ultimately empty product. To wit: In the category of $100 million–budget comic-book action-adventure films, White declared the “genre expertise” displayed by his great hero Steven Spielberg in the criminally ignored Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was “better than” the overpraised “dunglike banality” of Iron Man. Among neo-art films, Wong Kar-Wai’s little-seen My Blueberry Nights was “better than” that “endless, two-hankie Kubrick movie for fanboys,” The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

Most controversial was White’s assertion that the “kinetic art” to be found in assumedly schlocky Transporter 3 was “better than” that favorite of “impressionable teenagers,” The Dark Knight. White’s stance against the industry’s biggest moneymaker in this year of financial meltdown began with his original pan, in which he j’accused the film, saying it “fabricates disaster simply to tease millennial death wish and psychosis.” This opinion generated a mini-firestorm of hate mail on Rotten Tomatoes, the widely skimmed Internet movie-review site currently featuring a forum titled “Armond White of the New York Press May Be the Worst Film Critic Ever.” Among the more than 300 postings—for other critics, two comments is a groundswell—White was described as “sad,” “crotchety,” a peddler of “Cold War platitudes,” a hater of the common people, a “Christian boy,” an abuser of affirmative action, and a mindless typist. But at least none of the Dark Knight defenders suggested he get cancer from stuffing formaldehyde-filled coffins, “you stupid idiot,” as one Iron Man fan did.

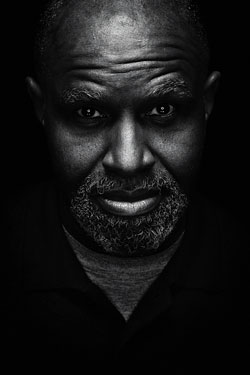

All this, along with sites like Armond Dangerous—Parsing the Confounding Film Criticism of Mr. Armond White, which offers coverage of White’s self- declared “humanist” jeremiad against Williamsburg-style “nihilism” (the page links to an article called “Hip to Be Square: Armond White vs. the Ghost Hipsters Part 16”), brings a smile to the critic’s eternally bemused, goateed face.

“Shows I’m doing my job,” he says, leaning back from his bento box in a Ninth Avenue sushi restaurant.

Now 55 and bearish-looking in his green down coat, gray-flecked stubble on his shaved, outsize noggin, White might have trashed The Wrestler—one of only four out of the 185 major critics on Rotten Tomatoes to do so—but he doesn’t mind playing the heel, the bringer of illusion-dissolving cold water, the man the peanut gallery loves to hate.

White says, “I don’t say these things to call attention to myself or to get a rise out of people. I say them because I believe them. We’re living in times when critics get fired if they don’t like enough movies. People don’t need to hear what mouthpieces for the movie industry tell them. They need to hear the truth.”

White says the difference between him and other movie critics—whether they write for The New Yorker or blog by the midnight oil, a practice he decried as little more than “a hobby” in a much fulminated-against recent piece—is that “they don’t see what I see. Where I’m coming from, they couldn’t.”

White does have his unique bona fides, including a twelve-year stint (1984–96) at the City Sun, the borderline-radical black weekly where he regularly slammed Spike Lee’s movies, referring to Clockers as “40 acres and a bunch of bull.” The youngest of seven children, and hailing from northwest Detroit, where his family “busted the block” as the first African-Americans to move into what had been primarily a Jewish neighborhood, White grew up in the era of white flight, the civil-rights movement, and Motown. His father played piano and worked for Ford after trying his hand at owning a gas station and a pool hall, neither of which lasted. “He taught us about the rights of the working man, and also that if you didn’t have anything to say, you should keep your mouth shut. But if you did have something on your mind, you should talk up, don’t keep it to yourself,” White recalls.

“We always went to the movies, every Saturday at least,” White says. “I used to love to see stuff like The Long, Hot Summer and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. To me, this was a window into the adult world. Now people watch movies so they can stay kids, which proves how infantilized the culture is. I wanted to see how grown-ups acted, in CinemaScope. Paul Newman and Elizabeth Taylor, the most beautiful people ever, on that giant image: It filled my head … Detroit was a great movie town then. We got Canadian TV, so I got to see stuff like La Dolce Vita, Jacques Demy’s Lola, 8½, all of them dubbed. Boccaccio ’70—these shorts by Fellini, De Sica, and Visconti—I must have seen that one twenty times.

“People would ask why I was watching foreign movies. But from early on, I knew I was different … Our parents raised us Baptist, then they got saved and became Pentecostal. There was always a lot of religion around. It had a big effect on me. I’m a believer. I think God is the force for ultimate good in the universe. He made the movies, didn’t he? If you cut me open, that’s what you’d find: the movies, Bible verses, and Motown lyrics.”

White’s narrative arc would take a turn in his senior year at Detroit’s Central High School, when he was assigned to write a paper on a book, any book. On a twirling rack in a drugstore, he spied a copy of Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, the second collection of Pauline Kael’s movie reviews. White had never heard of Pauline Kael, but he liked the picture of the camera on the cover. He began with the shorter pieces, then the famous Bonnie and Clyde essay, and went from there. Forty years later, long after coming to New York, meeting and befriending Kael, who in 1986 would nominate him for membership in the Film Critics Circle—which makes him something of what is generally called a “Paulette,” even if one critic says “there’s Paulettes and there are Paulloons”—White still retains that original copy of Kiss Kiss Bang Bang.

In between bites of tempura, White pulls out the book, now yellowed and coverless, from his bag, along with an accompanying, equally well-thumbed copy of The American Cinema, by Andrew Sarris, the former Village Voice film critic and grand channeler of the auteur theory that championed B-directors like Samuel Fuller and Nicholas Ray. As any sixties-seventies film nut knows, the pairing of the two books on White’s part was a symbolic act, being as Sarris (whom White studied with at Columbia) and Kael, the two most influential figures in American-popular-film criticism, were often seen as intellectual antagonists back in the days when writing about movies was considered to be something of a life-and-death matter.

This was White’s point. If the discourse of cinema, as he claims, has reached “the bottom”—victim of Roger Ebert’s thumbs up/thumbs down Roman Colosseum–style methodology, excessive blurb-mongering, fixation on weekend box-office reports, sheer laziness, etc., etc.—the fault lies not with the movies themselves. There will always be good movies. The problem is with the messengers, the sold-out, the politically and historically indifferent movie-critic sheep who have abdicated the passion-filled mantle of Kael and Sarris.

To anyone who used to care about such issues, this can be a compelling complaint. As for White’s corollary to the argument, his however-immodest proposal that he, and he alone, remains to tell the … well …

“Shit, you’re writing a piece about Armond?” exclaims one well-known film critic who would just as soon keep his name out of this. “Armond’s smart and all, I get a kick out of him, but do I really have to see him looking out of the magazine like he’s the last angry, honest man in the film culture?”

This being not an atypical attitude among members of the Film Critics Circle, White’s upcoming chairmanship figures to have its bumpy moments. (It has been pointed out that his “election” was not exactly by acclamation but rather because he was the only one who wanted the generally thankless job.) During White’s last reign, in 1994, he scheduled the awards dinner during the Sundance Film Festival, creating conflicts for some members. White defends this decision. “The circle is the oldest and most legitimate film-critic group in the country. We’re not the Dallas Film Critics Circle. If people wanted to carry water for penny-ante shit like Sundance, that’s too fucking bad. The circle comes first.”

White took a similarly purist stand when he railed against critics lobbying for free DVD screeners. “This is about the aesthetics of film reviewing,” he says. “We are obligated to see movies the way the public has to see them. If not, then become a DVD reviewer, don’t become a film critic.” Asking for product from the movie companies is a compromise of journalistic integrity, White says, declaring “the New York critics have been corrupted.” Despite his occasional soft-on-Bushism (and less-than- triumphalist celebration of Obama), it is his belief in “core values … the stuff I was brought up with” that is responsible for his reputation as “a hard-ass conservative,” White supposes—a characterization he rejects as a “smug and typical” reaction on the part of knee-jerk liberal readers and colleagues alike.

As you might imagine, self-respecting movie critics, traditionally being a touchy sort, have tired of getting called out like this. Last spring, following White’s now-infamous anti-blogger screed, Glenn Kenny, formerly of Premiere and now with his own Some Came Running site, counterattacked. In a post called “White Noise,” Kenny wrote, “White’s known for spewing bile at his peers in print, and then turning around and being quite affable to said peers in person—I’ve experienced it. And I’ve had it. So: Screw you, Armond.”

“I don’t say these things to call attention to myself or to get a rise out of people,” says White. “I say them because I believe them.”

Taking the high road, White says he has always attempted to “keep cordial relations with all critics.” Still, there have been incidents, such as one reliably eyewitnessed encounter during which White, after exchanging words with a well-known critic, asked the writer to step outside, though fisticuffs were averted. Nonetheless, White, who is about twice the size of the usual film critic and once seriously considered legally changing his byline to “The Resistance,” says the incident isn’t over with, not yet. “These people,” he says, “they don’t know who they are dealing with.”

Despite seeing as many as 400 films a year, White makes a point of keeping tabs on what the competition is doing. At a recent screening of Terence Davies’s new film, Of Time and the City, White was ticked to spy a second-string New Yorker reviewer seated a few rows behind him. This was typical of the disrespect to true cinema shown by the cultural gatekeepers, White says. Davies, director of The Long Day Closes, was a major international artist. Of Time and the City was Davies’s first film in eight years. Wasn’t that enough to get either David Denby or Anthony Lane, The New Yorker’s lead critics, to show up, or were they off handing out more mealymouthed awards for Milk?

A few nights after the Davies screening, White journeyed up to 42nd Street, where once upon a not so very long time ago, the film freak could put his feet on a sticky floor at the old Brandt Times Square theater and see a triple bill of Sergio Leone’s immortal trilogy, Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly for $1.50. The in-theater entertainment was also memorable, such as on the immortal evening when, right in the middle of Enter the Dragon, yours truly heard some skell in the balcony scream, “You’re sorry? You piss on my date and you say you’re sorry?”

“Only caught the tail end of that era,” White said wistfully, as he entered the labyrinthic, decidedly unsticky AMC Empire 25 theater on the Eighth Avenue end of the Giuliani-renovated touristscape. Ostensibly, White was there to catch a screening of Paul Blart: Mall Cop, a torturously unfunny comedy that would, of course, take in $32 million in its first weekend. White didn’t care about Mall Cop. After suffering through an hour, in true film-freak fashion, he left and snuck up the escalator to see Not Easily Broken, a black soap opera produced by the megachurch preacher T. D. Jakes.

In truth, despite the long-shot possibility of seeing treacle-free “positive” black characters, White wasn’t all that interested in Not Easily Broken either; it was A. O. Scott who persuaded him to go. The Times reviewer pulled what White calls “an Armond White,” i.e., he favorably compared the modest Not Easily Broken with the A-list Revolutionary Road, which Scott said “has energetically solicited the admiration of reviewers and awards-giving organizations.” To White, this was a potential infringement on his “better than” turf. As it turned out, White thought Not Easily Broken might indeed be “better than” Revolutionary Road, but they both sucked, so who cared? As for Scott, White pronounces, “Wrong again!”

Still, a film nut could do far worse than to spend several hours discussing cinema with White, hearing him say that “among Andersons,” the “comically humane” films of Wes Anderson, maker of Rushmore, are infinitely “better than” the “toothless Robert Altman gumming” of Paul Thomas Anderson, whose There Will Be Blood is a “symptom of everything wrong with the American experience.” Personally, I like White’s survival-of-the-fittest approach to film history, a macro version of the “better than” shtick. In this Darwinian praxis, all films must plead their case against all other similar films, with White as judge and jury. It is in this way that White can confidently tell you a film like Blade Runner is “effective for about fifteen minutes” and probably should have never been made, because there was no way it was ever going to surpass Fritz Lang’s Metropolis as a dystopic vision of the future.

It’s cracked, but fun. Sooner or later, however, you know you will crash into the densest of Armondic icebergs, i.e., Steven Spielberg. White regards the maker of E.T., Schindler’s List, and 1941 to be “the greatest of all American humanist directors, every bit the equal of John Ford … the measure by which all films and filmmakers must be judged.” The possible notion that Spielberg, eternal box-office boy-king of Hollywood, may embody the Reagan-Clintonist consumerism White claims has ruined serious film appreciation in this country is rejected with little more than a sardonic chuckle. For White, defending Spielberg is a waste of his breath, “a distraction.” If you can’t grasp the self-evident greatness of A.I. and Munich, that’s your problem, not his.

Light on this most confounding aspect of White’s criticism might be shed by an incident that took place in late 1977, when he was working for the Wayne State University newspaper. White was assigned to cover the local screening of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But Detroit’s being what it was in those days—they called it Murder City—there was no theater nearby deemed suitable to show the picture. A screening was set up in Southfield, then a nearly all-white suburb. White took the bus out there and walked several blocks to the theater. The film, needless to say, blew him away, especially the climactic descent of the giant mother ship, a moment White took to be nothing less than a revelation of the “face of God.” During the time White had spent in the theater, a heavy snow came down, nearly a foot.

“There I was, having seen that film, a truly great film, and I was walking through this blanket of pristine snow in the suburbs. I was the only one around. I’d never experienced a moment of such purity; perhaps I never will again.” As I contemplate White, it is hard to think of an image “better than” this: lone seeker making footsteps across unbroken field of blinding white, under the impression he’d just seen the face of God in a movie theater.