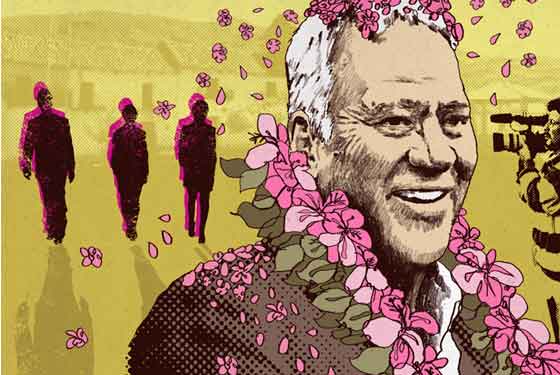

It’s hard to know whether to marvel or weep when James Carville goes into his Bill Clinton–meets–Looney Tunes act in Rachel Boynton’s knockout documentary Our Brand Is Crisis—the context is so morally topsy-turvy. As a high-priced consultant to the 2002 Bolivian presidential candidate Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (“Goni”), Carville gives a dazzling demonstration of how a politician should field an “oddball crap question” and steer it, in as few words as possible, back to the campaign’s message, which in this case is, “We’re in a crisis—and I’m the guy with the know-how to fix it.” The problem is that the blinkered patrician Goni doesn’t have the know-how to fix a stopped toilet, much less a country on the verge of economic collapse, with a disenfranchised indigenous majority howling to be recognized.

The process of “framing” Goni to look like something he isn’t could be the stuff of a rambunctious campaign comedy like Primary Colors or, for that matter, the documentary The War Room, which made Carville a political rock star. And parts of Our Brand Is Crisis are darkly amusing. But Boynton has done her own framing: This campaign is a precursor to tragedy. She opens with footage of an anti-government riot that came less than a year after the election. When the gunfire stops, the camera moves in on a boy sitting on the steps of a building, his head partly covered by his coat as if he’s grabbing a nap. It’s only when the camera is on top of him that we see the pool of blood. The image of that boy haunts Our Brand Is Crisis, so that the U.S. strategists who do a bang-up job of getting the wrong man elected to the wrong place at the wrong time look like agents of catastrophe.

These consultants, who work for the firm of Greenberg, Carville, and Shrum, aren’t the ultrasecret fat-cat right-wing corporatists of most muckraking documentaries. They even give lip service to progressive ideals. While acknowledging the immense profits to be made, they argue that with the export of American-style democracy comes the need for would-be leaders to market themselves to their people as well as to the rest of the economically globalized globe.

The film’s protagonist (Carville only beams into Bolivia to voodoo the troops) is Jeremy Rosner, who looks like Ben Stiller with the proportion of head to body normalized. Rosner describes himself as someone who listens “very aggressively,” although he doesn’t need sharp ears to hear that Goni—who was president of Bolivia in the nineties—is widely loathed for being an arrogant rich guy who gave jobs away to foreigners. What a challenge! While Goni lights his big cigar, members of the U.S. team explain the need to go negative, in ads and whisper campaigns, against the well-liked front-runner, the ostensibly more progressive Manfred Reyes Villa.

Boynton has extraordinary access—bewildering access, given the damning nature of what she gets. We’re right there with Rosner as he scrutinizes focus groups through one-way mirrors and gasps with delight at how ordinary Bolivians parrot the candidate’s crisis-branded message—tickled that he has steered this desperate country away from the charismatic younger candidate with the message of change. One American ideal (representation for all) has been trumped by another (win, win, win).

Only a naïf would be surprised by Our Brand Is Crisis, but only a nihilist would not be alarmed by the endless reverberations of Boynton’s case study—and by its suggestion of a systemic separation of modern politics and the national good. The U.S. good, too: The false promises underpinning Goni’s election paved the way for Bolivia’s current president, Evo Morales, seen here as the anti-imperialist spokesman for Bolivia’s coca-leaf farmers. So the reframing of our export of democracy is complete.

A different kind of reframing saves the by-the-numbers Bruce Willis vehicle 16 Blocks. This is one of those thrillers that come with their own architectural plan, laying out the parameters in the first fifteen minutes: distance to finish line (16 blocks); time (118 minutes); physical handicaps (the villain sneers, “He’s hung over, he has a bad leg, he has no gun!”); and psychological obstacles (“People don’t change!”). Mel Gibson thrillers follow the template “Make Mel Mad.” Bruce Willis thrillers use “Wake Willis Up.” Here he’s a disillusioned alcoholic with a gut. Will he be reborn as a moral man of action—i.e., a real man, with abs?

As the convict whom Willis must transport to the courthouse, the normally superb Mos Def does a Jerry Lewis–with–a–head cold number that only gets points for weirdness. A happier surprise is the smart work of director Richard Donner: 16 Blocks is all jumble and jangle—crowds, snarled traffic, and discordant car horns. The scariest moments have no music, like the sound of the bad guys’ car doors slamming offscreen. As for that reframing, it’s literal: The volatile camera gets in close, slicing off the tops of heads. There’s nothing like a hyper, faux-spontaneous technique to disguise when a movie has been focus-grouped to death.

Given how hyper most Hollywood features for children are, one of the happiest events of the year is the BAMkids Film Festival, on March 4 and 5. The four programs of shorts are routinely crammed with jewels, and the features are refreshingly not-in-your-face. I’ve seen two: the German slapstick fantasy My Brother Is a Dog, and the lovely and moving Swedish adventure Misa Mi, about a cranky 10-year-old city girl, grieving over the death of her mom, who discovers Mother Nature in the Laplands.

Our Brand

Is Crisis

Directed by

Rachel Boynton. Koch Lorber Films. Not Rated.

16 Blocks

Directed by

Richard Donner.

Warner Bros. PG-13.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.