Dan Brown’s pointy-headed potboiler The Da Vinci Code might actually be the threat to Christianity that its critics claim, but there are many threats out there—among them works by Deist scholars that speculate authoritatively on the multiple human authors and extra-divine political intentions of the New (and, for that matter, Old) Testament. Where Brown ups the ante is in spinning a matriarchal counter-theology that borders on pagan goddess-worship, and in making the reactionary-Catholic Opus Dei sect a bastion of homicidal zealots. Throw in car chases, gory murders, skulking bishops, a mysterious criminal mastermind, a self-flagellating killer albino, papyri in booby-trapped vials, and cryptogrammatic clues in masterpieces of Western art, and you’ve got yourself a publishing phenomenon that even a lot of churchgoers can’t resist.

The divinely uninspired adaptation by director Ron Howard and screenwriter Akiva Goldsman makes little of all this: The movie is a Shaggy Grail story without a whisper of passion—not even the passion for intellectual gamesmanship that buttressed the glop in the pair’s A Beautiful Mind. Given the furor surrounding its opening, The Da Vinci Code is an embarrassing nonevent. You can imagine Catholic leaders emerging from cinemas and telling their picketers to go home.

For a start (and a finish), Brown’s subversive thrust has been softened. In the book, it’s presented as fact that Jesus wasn’t divine: He was merely a major prophet until the emperor Constantine came along in the fourth century and—to shore up his own power—reorchestrated the religion around the whole Son of God thing. In the film, that’s just a theory—and, more important, a theory disputed by the nice-guy hero and “famed symbologist” Professor Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks). To clinch the deal, its proponent is an eccentric semi-invalid called “Sir Leigh Teabing,” a sodomite moniker if ever there was one, and played by an extra-fruity Sir Ian McKellen. Now, really: Whose side would you be on?

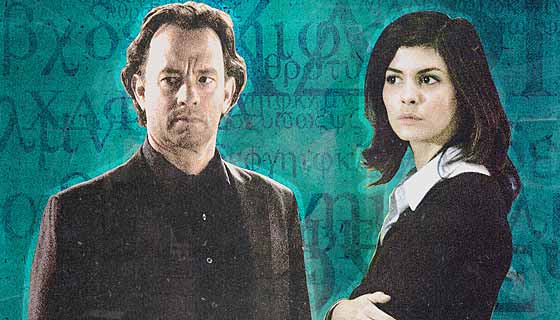

After an Opus Dei bishop (Alfred Molina) fingers Langdon for the murder of a Louvre curator, the symbologist and the French police cryptologist Sophie Neveu (Audrey Tautou) follow the dead heretic’s fancy clues in search of a secret that could transform the modern world. Their trek should at least produce some juicy set-pieces: Think what a haunted Catholic like Alfred Hitchcock would have made of this material. But Goldsman brings nothing—not even shameless Hollywood religiosity—to the party. Was the screenwriter so worried he’d be the target of anti-Semitic fusillades that he kept The Da Vinci Code at arm’s length? Maybe the job should have gone to a Catholic writer who would have identified with and preserved Brown’s wise-ass-altar-boy tone, because without it, there’s nothing left except generic thriller devices and a director too timid to give those a charge. Howard can’t even make something of what should have been a breathtaking murder scene: the Louvre at night. He blurs the backgrounds.

I felt sympathy for Hanks. This is obviously a money job, but it’s probably no fun for an actor with his smarts when there’s nothing to play—no subtext, no strong objective, and no characters of stature to go up against. He’s upstaged by his suit (a trim charcoal number). Pretty though she is, Audrey Tautou is a bigger washout. A textbook gamine (the text being Amélie), she seems bred for airy enchantment, not earthy gumption, and her very approximate English turns even rudimentary dialogue into a linguistic adventure. She was obviously cast because the script said, “French girl,” and the studio execs said, “Call Tautou’s agent”—the way the script said, “French cap-i-tain,” and the execs said, “Call the Godzilla guy’s agent, Jean Reno.” Another bad call was casting the pale blond Englishman Paul Bettany as the demented albino Silas. He’s a fine actor, but he’s slender and diffident; he has to work too hard to convey the volcanic inner life that’s meant as a counterpoint to the abominable-snowman exterior.

If there’s anything to be learned from this dud, it’s that when you adapt an explosive property like The Da Vinci Code, playing it safe isn’t safe: Either swallow hard and make the damnable thing or give it to someone with more guts and/or less to lose. Here is a saga that bombards the very foundations of Western religion. But onscreen, there seems to be absolutely nothing at stake.

X-Men: The Last Stand is, like The Da Vinci Code, undermined by impersonal direction, but this time it isn’t fatal: There are still lots of neat-o special effects. As in the Marvel comic and the last two film installments (directed by Bryan Singer), the gimmick is that evolution has produced a class of special individuals reviled or feared by the rest of humankind (and in heartbreaking cases, disowned by their own parents). We’re talking about shape-shifters, mind readers, telepaths, flame-people, ice-people, people with odd protuberances, and people who don’t just complain about the weather but actually do something about it. Under the care and tutelage of Professor Xavier (Patrick Stewart), more and more of these lost souls have embraced the label mutant the way gays have embraced the label queer: They are Mutant and Proud. The problem is the ones who are Mutant and Angry, led by Xavier’s combative counterpart, Magneto—played by Ian McKellen, once again stirring the pot.

In this (alleged) Last Stand, a mutant’s wealthy and distraught father (Michael Murphy) has developed a serum that can instantly de-mutanize, which enrages Magneto and a like-minded troupe of hothead young’uns, including a guy with retractable porcupine blades and a muscle-bound Cockney (“Juggernaut”) who has never met a wall he couldn’t pulverize. They liken the use of the serum to genocide and vow to destroy the “cure”—along with a lot of Homo sapiens (the term is an insult and always hissed). The movie has a very wild card that could turn out to be the militants’ ultimate weapon: Xavier’s dull assistant Jean (Famke Janssen), who sacrificed herself for her comrades at the end of X2, emerges from a lake with certain protective psychological barriers in her brain removed (long story). Her uncontrollable female fury unharnessed, she’s now called Phoenix and itching to suck dry or disintegrate the men who thought they could tame her. Janssen isn’t the world’s most animated actress, but she doesn’t need to be with FX like this.

Too bad the FX people couldn’t jazz up the new director, Brat—I mean Brett—Ratner, a youngish Hollywood hotshot with the skills of a briskly competent traffic cop but no discernible vision. With all the apocalyptic doings in The Last Stand—including the disintegration of some major characters—there ought to be a sequence or two that is not just impressive but lyrical, awe-inspiring, operatic. But there’s nothing as showstopping as the scene in X2 in which Magneto sucked the iron out of a guard’s bloodstream and, with supreme elegance, sailed out of his prison cell on a sort of metallic carpet. Ratner doesn’t do elegance, so this is just another big-budget B-movie.

It’s a fast and enjoyable B-movie, though, and Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine brings some good stormy drama to the proceedings. (It’s not going to come from the character called Storm, played by the monotonic Halle Berry, or the increasingly stick-in-the-mud Rogue of Anna Paquin’s.) As a mutant-human diplomat, a blue hairy beast, Kelsey Grammer is all backslapping heartiness. Why is it that the only genuine uniters-not-dividers are in monster movies?

The Da Vinci Code

Directed by

Ron Howard.

Columbia Pictures. PG-13.

X-Men:

The Last Stand

Directed by

Brett Ratner.

20th Century Fox. PG-13.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.