Chris Pratt, played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, is the perfect patsy-hero for the crafty little minor-key thriller The Lookout: a young man who has sinned in his own eyes and is also brain-damaged—compromised both morally and neurologically. When we first see him, he’s “Slapshot” Pratt, a high-school rich-kid hockey star who’s so certain of his indestructibility that he sails along a Midwest country road sans headlights, the better to show off all the fireflies (they’re mating) to his girlfriend, his buddy, and his buddy’s girlfriend—two of whom don’t survive the subsequent collision. Now, he spends his days at an “independent life skills” center and his nights as a janitor at a small bank, where he’ll never have the cognitive function to rise to the level of teller. “Sometimes I cry for no reason,” he writes in the journal he keeps in the battle to make sense of his life.

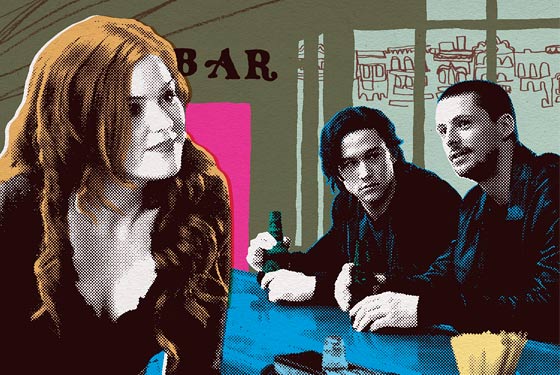

The Lookout is the directing debut of the screenwriter Scott Frank (Out of Sight, Minority Report), who reportedly wrote the script years ago—well before Memento, in which a brain injury plays havoc with both the protagonist’s short-term memory and the movie’s syntax. For those with a taste for neo-noir, it might be disappointing that Chris’s handicap doesn’t generate seismic spatial-temporal dislocations. Frank’s ambitions are comparatively modest: to deliver a nice, tight genre piece with people you like watching so much that you barely feel the director’s squeeeeze until you suddenly can’t breathe. The forlorn Chris finds himself befriended at a bar by Gary Spargo (Matthew Goode) and a babe who calls herself Luvlee (the luscious Isla Fisher). Gary was a big fan of his high-school hockey playing! Luvlee was such a big fan she can’t believe she’s kissing Slapshot Pratt! The poor prat—I mean, Pratt—is the easiest bank-employee mark imaginable.

Gordon-Levitt is a major tabula rasa actor. It’s simpler to say what he doesn’t do wrong—anything—than what he does right. As in Mysterious Skin and Brick, he’s a minimalist: no fuss, no placards, no Method sense-memory exercises. You don’t catch him “playing” brain-damaged. You know his Chris is in chaos by the way he doesn’t seize the space, by what he takes away from the character. His feelings run deepest when that rubber face goes slack. Gordon-Levitt is a great re-actor, and he bounces off some barnstormers here. As his intemperate blind roommate, Lewis, nice-guy-actor Jeff Daniels gets to wallow in the head of another self-righteous jerk (the last one was in The Squid and the Whale), and Daniels’s relish for playing a man with a chip on his shoulder the size of a tractor and nothing left to lose makes you love the character beyond reason.

In Match Point, Matthew Goode played Jonathan Rhys Meyers’s mysteriously welcoming upper-class tennis partner—“mysteriously” because Goode couldn’t help but give the character an impish subtext, as if some skeezy punch line were coming (except that Woody Allen forgot to write it). In The Lookout, he’s playing an American, but the wiles are entertainingly English: It’s that mocking sincerity—that ironic fatuous niceness. Goode’s Gary is just the friendliest guy! He’s seductive even when you know where the movie is heading—and when the editor, Jill Savitt, steals a beat from his close-ups to give you subliminal willies. It’s almost a relief when the double entendres stop and Gary shows his true, feral colors.

Frank’s writing is razor-sharp, his filmmaking whistle-clean. As a fan of sharp razors and clean whistles, I enjoyed The Lookout—yet I did feel let down by the climax, which ought to have been blunter and messier and crazier and more cathartic. It sounds churlish, I know, but a thriller with a hero like Gordon-Levitt’s Chris should be more of an act of sympathetic imagination. The payoff needed to be more brain-damaged.

Reign Over Me is the rare studio film with the fullness of a novel—a novel that reels and overreaches and never finds its footing. The writer and director, Mike Binder (The Upside of Anger), brings his screwball-sitcom temperament to a fictional premise that would stagger our most ruminative tragedian. Five years after the death of his wife and three daughters in one of the planes that crashed into the World Trade Center, Charlie Fineman (Adam Sandler) remains in a state of extreme denial—he seems more brain-damaged than the hero of The Lookout. Whizzing around Manhattan on a scooter, he’s hailed by Alan Johnson (Don Cheadle), his college roommate and dental-school chum. While Alan recalls their relationship, Charlie nods politely (“Cool, cool”) and then prepares to go on his way. He doesn’t want to remember anything.

In some ways, Charlie isn’t a stretch for Sandler. His comic shtick has always depended on him living in his own head and being self-servingly slow-witted. The persona is a hostile one—passive-aggressive with the odd ferocious ejaculation. But Sandler was surprisingly soulful as an overgrown adolescent lashing out at the world for its unreliability in Paul Thomas Anderson’s tipsy romantic fantasia Punch-Drunk Love. And as Charlie Fineman, he’s like a dammed-up Bob Dylan—he even sports a shaggy Dylan-circa-1969 hair mop and a mumble that seems to issue straight from his sinuses. He’s always ready to boogie—especially when someone wants him to acknowledge the death of his family. The worst are his wife’s parents (Robert Klein and Melinda Dillon), who’ve clung to the tragedy and, rather selfishly, feel they need his presence to help them cope. Cheadle’s Alan isn’t that extreme, but he does enlist the aid of a psychiatrist played by an oddly cast—but not bad!—Liv Tyler.

Binder, to his credit, isn’t glib. He doesn’t overrate Freudian catharsis; for Charlie, facing his pain would be only the beginning of a journey ending God-knows-where. But I still found Binder’s psychotherapeutic, well-made-play universe inadequate for exploring a loss so monumentally horrible. And I’m not sure the movie can bear the sociological weight of 9/11. (Is Charlie supposed to be a stand-in for all of us?) The pall overwhelms the film’s lighter subplot, in which Alan confronts the traumas in his life: the tension with his wife (Jada Pinkett Smith) over late nights with Charlie and the screwy ardor of a patient (Saffron Burrows) who tries to seduce him and then charges him with making inappropriate overtures. (Charlie has a funny line about his friend’s stalker: “She’s crazy with a side of crazy.”) Charlie and Alan are supposed to help each other recover their old selves—and the mix of tragedy and deadpan comedy and buddy-buddy uplift is … icky.

Cheadle is a blessedly centered actor, and Sandler is up to his inevitable let-it-all-out Big Scenes. (The timing might be a tad unfortunate for the one in which he points a gun at two NYPD cops, who carefully disarm him instead of shooting him 41 times.) But the film is slick when it needs to be raw, tidy when it needs to sprawl, and amorphous when it needs to focus. The terrible title comes from the Who’s “Love, Reign o’er Me,” and I can imagine Binder vowing to make a movie that builds to the same kind of primal rock-and-roll wail for connection. But his instruments don’t play in tune. And you can’t do primal wails with a kazoo.

Lefty peaceniks who object to the red-meat vigilante action genre on moral and political grounds but down deep wonder if they’d enjoy watching evil right-wing war criminals get their heads blown off should check out Shooter, which is based on a novel by Washington Post film critic Stephen Hunter about a sniper named “Swagger” who’s set up by genocidal mercenaries (led by human-rights activist Danny Glover at his Snidely Whiplash best) to take the fall for a political assassination, then decides he doesn’t need subpoena power to do a little government housecleaning. As Swagger, Mark Wahlberg explains his cynical view of American democracy to a sympathetic FBI agent (Michael Peña): “Gharfrasrt isgotrs isgoivt hjnbfkjstusg trobhforgalit”—which I know will be a powerful statement when I get the DVD and read the closed captions. The best parts are when Swagger and his various spotters trade longitudes, latitudes, rotational-earth vectors, and wind speeds, and then Swagger squeezes the trigger and the top of a bad guy’s head goes “Cush!” On a more sobering note, this is the first big-studio action picture (the director is Antoine Fuqua) with some of the disgusted, bloody nihilism of the post-Vietnam era.

BACKSTORY

Though Reign Over Me is a fictional 9/11 movie, some families did perish together on those flights, and eight children died on two different hijacked planes: five on American Flight 77, ranging from 3 to 11 years old, and three on United Flight 175, which included the youngest person to die on 9/11, 2-year-old Christine Hanson. One set of siblings died on Flight 77, Zoe and Dana Falkenberg, ages 8 and 3, who were traveling to Australia with their parents, Charles and Leslie.

The Lookout

Directed by Scott Frank.Miramax. R.

Reign Over Me

Directed by Mike Binder. Sony Pictures. R.

Shooter

Directed by Antoine Fuqua. Paramount. R.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.