The bleak film of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix smothers the final embers of the series’s childish wonder, ushering in a climate of repressed sexuality, paranoia, Fascism, madness, death, and acne. (That last is not by design but comes with the territory.) This is not a family movie. It’s not even a borderline gothic horror movie, in the manner of the third and fourth (scary) Potter installments. Directed by David Yates, Order of the Phoenix is Orwellian. The palette is grainy and dank, the faces dour, the hero’s alienation beginning to fester. Hauled before a hostile tribunal to explain his use of magic in the presence of Muggles, the hormonal, beleaguered Harry recounts the attack of the swirling Dementors: As they drew the breath from his body, he says, “it was as though all the happiness had gone from the world.” That’s how the whole movie feels—Dementored. Adding to the unease is the altered appearance of its out-of-joint trio, now on the far side of puberty, each growing at a different rate. Hermione (Emma Watson) is developing into a broad-shouldered Amazon. Ron (Rupert Grint) is even hulkier and might consider upping his dose of benzoyl peroxide. Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) hasn’t quite kept pace. His visage is pinched: You get a glimpse of the fortyish accountant beneath the teenage wizard. The prepubescent cuties they once were are seen fleetingly, in flashback. Ah, for the halcyon days of vomit-flavored candy and Quidditch.

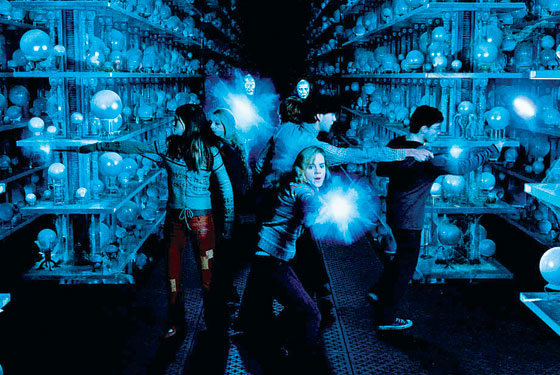

Did I mention that, for all its portentousness, this is the best Harry Potter picture yet? In some ways, it improves on J.K. Rowling’s novel, which is punishingly protracted and builds to a climactic wand-off better seen than read. (I can’t wait to ogle the Imax 3-D version.) Yates directed the great 2003 British mini-series State of Play, a literate newspaper drama with a vein of sublimated violence. (It was too little noticed on these shores when it popped up—with a lot of irritating commercials—on BBC America.) Yates and his crack editor, Mark Day, let loose with horrific montages: Order of the Phoenix is haunted by the image of Lord Voldemort (Ralph Fiennes), his features still primordially puttyish, in a business suit on some sort of subway platform. He stares at Harry inscrutably. Is there the faintest trace of sadness? Voldemort is now Harry’s most intimate companion. The Ministry of Magic has mounted a campaign—through its Pravda-like newspaper, the Daily Prophet—to discredit the notion of the dark lord’s return. Fellow pupils regard Harry warily. A little Irish tuffy called Seamus says his mum thinks Harry’s a loy-er. Hogwarts headmaster Dumbledore (Michael Gambon) has turned frosty and elusive.

Above all, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is dominated—nearly subsumed—by Imelda Staunton as Dolores Umbridge, the latest and most bloodcurdling Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher. Plump and pink, a tea-cozy Fascist, Staunton’s Umbridge is the distillation of every twisted, reactionary instructor you’ve ever had. Palpably loathing her students’ youth and freedom, she metes out punishment with mocking gentility, with a frozen smile more enraging than any angry rebuke. What inspired the creation of this freak? Rowling came of age when the English director Pete Walker was churning out nasty seventies melodramas like House of Whipcord and Frightmare, films that fed on the tension between Britain’s swinging counterculture and its repressed and repressive guardians of middle-class propriety—whom Walker depicted as semi-delusional torturers and cannibals. I wonder if Rowling saw them—and was chilled to the marrow as I was by Walker’s leading lady, Sheila Keith. Or perhaps this figure is universal: In no other book do you feel as viscerally the pagan fury out of which the Potter series must have been born. In addition to being a sadist, Umbridge represents an executive branch of government unchecked—liable to hold an inquisition at the first whiff of insolence, using the citizenry’s fear as a pretext to abolish civil liberties. Where Rowling goes soft is in offsetting Umbridge and her ministry with Dumbledore, a good liberal patriarch—albeit an increasingly fragile one. (The death of Richard Harris, who originated the role, only reinforces our sense of Dumbledore’s vulnerability.)

The trim adaptation by Michael Goldenberg irons out a few of Rowling’s dissonances—among them the escalating morbidity of Harry’s protector, Sirius Black (Gary Oldman), whose fate in the novel makes more emotional sense. He doesn’t solve the problem of Cho Chang (Katie Leung), still a cipher (and sexless) even in the course of the smooch heard round the world. (For all the hubbub, you’d think she goes down on Harry.) Ron’s sister, Ginny, who’s looking more in the books like Harry’s true love—which means she’ll either die in his arms or bear him little wizards—is virtually anonymous here. But Helena Bonham Carter adds a surreal (and ear-splitting) note as some kind of a shrieking she-demon. And there is an enchanted turn by a young actress new to movies, Evanna Lynch, as the queerly private Luna Lovegood: This flake flutes her lines, but not always on key. (You like her but wouldn’t want to be stuck with her in a train compartment.) The supporting cast is the usual embarrassment of British riches: Maggie Smith, Alan Rickman, Emma Thompson, Robbie Coltrane, David Thewlis, Brendan Gleeson, Richard Griffiths, Fiona Shaw, Julie Walters, Jason Isaacs. (Where is Bill Nighy? Vanessa Redgrave?) After collecting their Hollywood paychecks, these actors now have no excuse not to do more plays for scale.

Having confidently proclaimed that David Chase would learn the lesson of John Updike’s Rabbit and not kill off Tony Soprano too early (Come on, folks, he’s dead, dead, dead), I’m loath to predict what July 21—and the final Potter book—will bring. But the film of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is the best enticement imaginable. It rekindles the dread, the ache in your stomach that says, “He can’t die!”—and at the same time, “How can he defeat everything racist, repressive, and murderously Fascistic in the world without making the ultimate sacrifice?”

George Ratliff’s Joshua is a pretentious, secular, art-house remake of The Omen. It centers on a demonic kid (Jacob Kogan) and the clueless parents (Sam Rockwell, Vera Farmiga) who suspect the truth too late—and when they do, can’t convince anyone they’re not nuts (and who thereby go nuts). The movie works on its own terms. It’s hard not to be creeped out as the boy hovers over his smiley infant sister, and by the bumps and changes of pitch on the parents’ baby monitor. (Those things are an endless source of anxiety, especially when they pick up stray signals; mine once broadcast a shrink telling a friend about what a lousy, inattentive therapist she’d been that week.) But the line between eeriness and tedium is fatally fluid. And if not Satan, what’s eating this kid? The most interesting question posed by Joshua—as well as by the charmingly improbable Swiss comedy Vitus—is whether the average affluent, ambitious parent (in Switzerland or on the Upper East Side) is more disturbed by the prospect of a gifted but deeply screwed-up child or a happy but average one. The answer in many cases might give even Joshua the willies.

The prolific Patrice Leconte takes a break from mythic, life-and-death scenarios with My Best Friend, a sitcom that threatens to take a rockier emotional path before swerving back into the comfy zone. It’s better when it’s threatening, but Leconte knows his audience. Daniel Auteuil plays François, a ruthless antiques dealer suddenly confronted by his own friendlessness. Mais non, he tells his business partner (Julie Gayet), I do too have friends! Prove it, she says, kicking off that surefire farce staple, the potentially bankrupting bet. Auteuil begs a taxi driver, Bruno (Dany Boon), to tutor him in the fine art of eye contact, empathy, etc. Much hilarity (and poignancy) ensues. An hour in, there’s a shattering plot twist, but the shards reassemble themselves magically in time for a pulse-pounding climax on the French Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? The film has been praised for probing “the meaning of friendship,” which I guess comes down to someone you phone when you’ve already asked the audience and used your 50-50.

BACKSTORY

After Daniel Radcliffe finishes production on Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (due out in November 2008), he’s coming to New York in all his earthly glory—in Equus. The 1973 classic just wrapped a West End run and is set to hit Broadway in spring 2008. The hoopla surrounding young Potter’s full-frontal exposure led to advance ticket sales of over £2 million. And the experience seems to have freed his mind as well as his body. “Once you’ve been onstage naked in front of 1,000 people, you really feel you can do almost anything without inhibition,” he said.

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix

Directed by David Yates. Warner Bros. Pictures. PG-13.

Joshua

Directed by George Ratliff. Fox Searchlight Pictures. R.

My Best Friend

Directed by Patrice Leconte. IFC Films. PG-13.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.