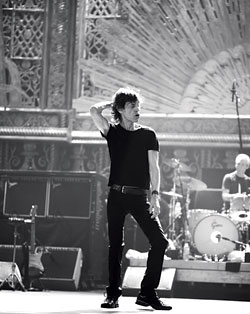

The joke that Martin Scorsese seizes on throughout his megawattage Rolling Stones concert movie, Shine a Light, is that the band’s members have been asked “How much longer can you stay together/productive/alive?” every year since Mick Jagger was a soft-faced boy who looked barely out of grammar school. Does the movie penetrate the mystery of the group’s supernatural properties of regeneration? No: That’s beyond Scorsese’s ken—and, very likely, beyond the Stones’. What motivates him is both shallower and more fundamental. He stands before Jagger like a pagan sun-worshipper. Merely to capture this magical energy—this dynamo—on film would be triumph enough.

The pretty good news is that he pretty much has—and I’ll drop those annoying modifiers if the Imax version (which I haven’t seen) is as transcendent as I’ve heard. Scorsese does everything possible to get inside the event (or, really, the two events, both at New York’s Beacon Theatre, one a benefit hosted by birthday boy Bill Clinton). He brings together a Marvel Comics–worthy assemblage of super-cinematographers (among them John Toll, Andrew Lesnie, Robert Elswit, Emmanuel Lubezki, and Ellen Kuras) under the leadership of Robert Richardson (Albert Maysles—of the Maysles brothers, of Gimme Shelter—is even in there). He comes at the Stones from every imaginable angle. He voodoos the footage into a fluid whole. But Shine a Light needs a little push—Imax, 3-D (it worked for Hannah Montana!), Odorama, Hells Angels … some extra element of liveness. Because Jagger’s animation doesn’t draw you in. The light bounces off him and into outer space.

Scorsese is canny enough to make Jagger’s elusiveness the movie’s launching point: The director appears in a black-and-white prologue, trying to connect with the peripatetic bandleader about the set, the camera placement, the song list … But Jagger’s motor runs too fast—too fast even for Scorsese, king of the speed-freaky motormouths. He seems unwilling to inhabit the same present, to open himself up for an instant. And that’s true in concert, too, especially in signature jitterfests like “Jumping Jack Flash,” where his automatic pilot is faster than ever: He’s like the newest Terminator model, his rope-thin torso flicking determinedly, his cheeks sunken all the way to the armature. If you could replicate his movements exactly—every lightning stutter-step and bob and finger wag—would you be able to discern what he was thinking? More likely you’d spontaneously combust. It’s better when Jagger shares the spotlight with guest stars: with a smitten Jack White, looking like Edward Scissorhands’s pudgy brother; with Buddy Guy, who has a different kind of resonance (lungs, soul) and is smart enough to make Jagger come to him; and with, amazingly enough, Christina Aguilera, who brings much-needed va-va-voom to a stage full of old toothpick men—and who reminds you that Jagger, however self-contained, isn’t just about autoeroticism. Watch the way those pillowy lips form the word “Ag-gwee-lair-ahhh.”

In the old days, Jagger seemed to be taunting us—or, more likely, his stuffy British headmasters and their blue-haired wives—by parading around the stage as everything most fearsome, the cock of the walk as a huffy black androgyne. Now he taunts us with his stamina. Scorsese interpolates old interviews sparingly but with witty precision: “How long do you think this can go on?” “Uh, well, another year…” Keith Richards’s survival is a persistent source of wonder: Rock history is full of people who tried to keep pace with him, drug-wise, and did not survive—Brian Jones among them. Yet here he stands, looking like Freddy Krueger’s gypsy grandmother but alive and ridiculously happy. There’s Charlie Watts in old clips puzzling out his own identity, only fleetingly grasping his own magnificence—and here he is now, still no closer to the meaning of it all but amused by the circus. (That the drummer of the Rolling Stones is a Buddha of centeredness is some kind of great cosmic joke.) Everyone in the band seems to acknowledge that however slick the corporate entity called the Rolling Stones has become, there’s something unstable in its very DNA. I remember Keith in an old Musician interview saying the secret to their sound was that they always seem on the verge of falling apart but never do. That’s not how I’d describe them today—they’re tighter than ever. But the blend of driving rock and ramshackle blues is inherently fraught. It takes a lot of nerve and discipline and, yes, stamina to court entropy while making sure the center holds. (Anyone who saw the Replacements live knows how discomfiting it is to hear a band really on the verge of falling apart.)

My favorite rock-concert movies, Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense and Neil Young: Heart of Gold, are organic: They chart a miraculous path from sound to soul. Scorsese stays on the outside, as befits his temperament and his subject. Yet there is, amid the whirligig spectacle, a spark of connection. Scorsese edits like a rock musician who never had the chops (or the breath—he’s an asthmatic) to take the stage. At the end of Shine a Light, the camera follows the Stones out of the Beacon Theatre and Scorsese waves it up up up over Manhattan Island. The little guy has kept up with his rock-and-roll gods. Now he shows off his own brand of potency by rising above the throng.

On the surface, Kimberly Peirce’s Stop-Loss doesn’t bear much resemblance to her momentous debut, Boys Don’t Cry, the story of a young woman (Hilary Swank) who pretended—joyfully—to be a good ol’ boy and got raped and murdered when her dumbfounded drinking buddies couldn’t process their little chum’s new identity. But something ties the two films together. For a Feminist Studies type, Peirce has an uncanny knack for getting inside the heads of young men, for making you feel how powerfully their identities are bound up in their masculine relationships and rituals. Stop-Loss doesn’t come together, but in its ungainly way it evokes the anguish of American shit-kickers who’ve lost all sense of autonomy.

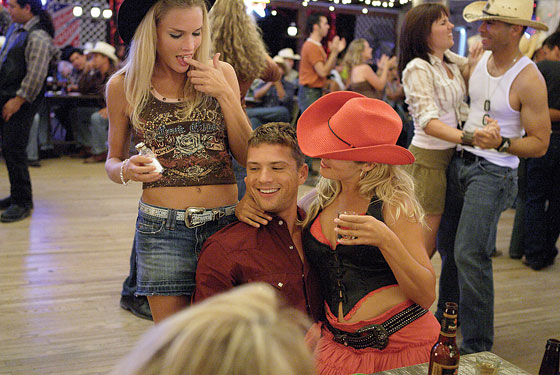

The movie centers on three Texas soldiers (Ryan Phillippe, Channing Tatum, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt) who return from Iraq after an ambush that left some of their friends dead and maimed and another barely suppressing his inadvertent killing of civilians. That battle is the opening sequence, and Peirce makes you understand on a gut level the adrenaline-fueled hyperawareness of these men at a checkpoint, as they almost fire on a car with a family speeding toward them, then the unreality of the moment when insurgents in another speeding car open fire on them. When it’s all over and the Americans roll into Texas on a bus, ready to be discharged, you get a palpable sense of how wound up they are—itching to get drunk and laid and court oblivion. They barely make it through the parade and speech of a U.S. senator before they’re throwing back shots and retching and punching people out and having the requisite war flashbacks.

The film’s title refers to the presidential prerogative of extending a service member’s enlistment contract beyond its expiration date in times of war—a “backdoor draft” that, according to the movie’s postscript, has kept 81,000 Americans and counting in uniform. The most stable of the three protagonists, Brandon (Phillippe), learns he has been stop-lossed when he goes back to base to get his discharge papers, and although he comes from a military family and has no evident problems with the war, he refuses on the spot—then punches out two guards and goes AWOL. Phillippe has never struck me as much more than a pretty face, but his underplaying works here. He doesn’t transform into a grandstanding actor; he looks completely at sea. When his pal Steve’s fiancée, Michelle (Abbie Cornish), volunteers to drive him to Washington, D.C., to get help from a senator who promised him the world, Stop-Loss becomes a road movie—an odyssey that leads the pair to the family of a lost friend, a fleabag motel where another AWOL stop-loss casualty hides out with his wife and sick kid, and a hospital where Brandon’s squad mate Rico (Victor Rasuk) lies blind and severely maimed.

It’s ironic that Stop-Loss loses its momentum when the characters go on the road. Yet Rasuk—the star of Raising Victor Vargas—gives a stunning performance: He plays Rico as upbeat, almost content, knowing that Iraq was “payback for 9/11” and determinedly building up his one remaining bicep. And by rights this part of the film should crawl along and go essentially nowhere. Brandon, whose life is bound up in his role as a soldier, has no real recourse; and Peirce and her co-writer, Mark Richard, have no answers. The power of Stop-Loss—and this is no dumb joke—is that it shows its hero between Iraq and a hard place.

In The Flight of the Red Balloon, the great Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsiao Hsien uses Albert Lamorisse’s 1956 masterpiece The Red Balloon as a springboard for his own masterpiece—a distinctively modern and allusive one, yet so tender and plaintive that you understand what Hou is up to on a preconscious level. Lamorisse’s balloon now floats above Simon (Simon Iteanu), a 7-year-old Paris boy whose single mother, Suzanne (Juliette Binoche), can barely keep her life together, and whose new nanny, Song (Song Fang), is a quiet, attentive film student who thinks about making her own version of The Red Balloon.

The film is built on contrasts, on invisible currents and crosscurrents. There is the steadiness of Hou’s camera and the chaos of Suzanne’s world, with its implicit toll on the psyche of her little boy, lost amid the clatter. Suzanne writes puppet shows in which her mythical characters are transfigured, yet her life is miserably untranscendent. She sits amid piles of paper, her peroxided hair clenched, wailing into her phone, high-strung and bereft. Binoche improvised her lines, fumbling her way along like Suzanne, and the tension between her myopia and Hou’s higher gaze gives the film its center, its meaning.

The Flight of the Red Balloon is full of allusions to filmmaking, even to the art of making a balloon pulled around by a person look as though it’s floating free. That balloon stands in for Hou and Song; at times it has the impishness of a Miyazaki god. It watches over this neglected child, helpless to intervene. Yet its beneficence—and the art that gave birth to it—makes you look to the sky, and hope.

BACKSTORY

After Reese Witherspoon cited “irreconcilable differences” when filing for divorce from Ryan Phillippe, the rumor mill pointed to his Stop-Loss co-star Abbie Cornish as the other woman. With the movie’s release, the old tabloid story is reborn. Phillippe says it’s unfair to direct blame at Cornish: “I don’t think an outside person can ever cause a divorce,” He told W. “I had difficulties … in my marriage long before I ever met her.” And anyway, he described his relationship with Cornish as merely a friendship “in a really difficult situation.” Witherspoon is now dating Jake Gyllenhaal. No hard feelings from Ryan: As he told Howard Stern, “He’s a good dude.” Ryan Phillippe in Stop-Loss.

Shine a Light

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Paramount Classics. PG-13.

Stop-Loss

Directed by Kimberly Peirce

Paramount. R.

The Flight of the Red Balloon

Directed by Hou Hsaio Hsien

IFC Films. NR.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.