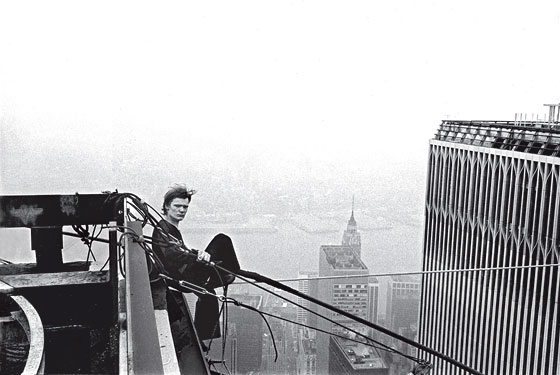

Frenchman Philippe Petit walked on a wire between the towers of the World Trade Center in 1974, and when he came down (in police handcuffs), American reporters pressed close to ask why, why, why. The question, of course, was absurd. A third of a century on, it still gets Petit going: “Very American finger-snapping … I did somezing magnificent and mysterious and I got a ‘why,’ and ze beauty of eet is zat I don’t have a ‘why.’” James Marsh’s rollicking documentary Man on Wire asks not Why? but How the hell? Marsh chooses to tell Petit’s story in the form of a heist picture, part talking heads, part period footage of Petit honing his balance, part Mission: Impossible reenactments of the day and night and day in which the team made it up to the 104th floor with shackles and wires, hiding under tarps from security guards. Those reenactments—usually realism-busters in this sort of doc—are transparently fake but edited with such urgency that they snap right into place. They’re bridges to the main event, the “coup” (as Petit calls it), the hero’s dance from rooftop to rooftop (balance, demi-plié, fouetté) above the great nothingness—and all of it captured on film. “Death ees very close,” Petit narrates. It’s a relief that he’s telling his own story and we’re not stuck with Werner Herzog ruminating on the Wire of Life and the rebel who went splat.

The Wire is Life, though. There’s a girlfriend involved, Annie Allix, who says of Petit, “Each day is like a work of art to him.” This is his manifesto: Seize the space, fill the void, defy society’s soul-killing laws, define yourself through action. Very existentialist, very inspiring, unless you happen to be driving under the Sydney Harbor Bridge when you see a lunatic up high and hit the brakes and someone crashes into you from behind, or something heavy lands on your car roof with a sickening thud and you die. But prudish objections fade. There’s a long shot of Petit on that bridge in which you can’t see the wire, and it’s the damnedest thing: He looks like he’s walking on the air. There’s another shot of him suspended between the towers of Notre Dame: Inside, priests are prostrating themselves before the altar, unaware that there’s a man above them swaying on a tiny wire and juggling. We must learn to take our miracles where we find them.

It goes without saying—and, happily, Man on Wire doesn’t say it—that all this happened in a more naïve time, that today the notion of foreigners with fake I.D.’s slipping past security guards into the Twin Towers has a different meaning. So does the prospect of falling from the sky. The most miraculous thing about Man on Wire is not the physical feat itself, 1,350 feet above the ground, but that as you watch it, the era gone, the World Trade Center gone, the movie feels as if it’s in the present tense. That nutty existentialist acrobat pulled it off. For an instant, he froze time.

What a world it would be if people got as fervent about Man on Wire (that’s a real guy up there!) as they do about The Dark Knight (that isn’t!). Or even one-tenth as fervent. Entertaining, mind-opening docs open every month—this year’s crop includes Taxi to the Dark Side, Operation Homecoming, and Full Battle Rattle—but none has broken through to a wide audience. Now comes the latest winner, Margaret Brown’s penetrating The Order of Myths. Brown explores a potentially enraging subject—rigidly upheld racial segregation in the country’s oldest Mardi Gras celebration, in Mobile, Alabama—but her touch is so unforced and her gaze so open that no one is bruised. The situation is heartbreaking, the people … inured. Set. Following rituals passed down from evil times, too timid or unimaginative or, maybe, although it’s well below the surface these days, racist to challenge them. You just don’t know.

Brown grew up in Mobile, but she doesn’t put herself in the movie and doesn’t tip us off to any insider knowledge until the very last—brilliant, rug-pulling—interview. She takes an anthropological view; she studies the rituals, the props, the antebellum hand-sewn gowns with their long trains, the diamonds and the moon-pies. There’s a white parade and a black parade, a white king and queen and a black king and queen. It’s that way, the whites say, because the blacks want it that way. It’s such a good time. The skinny blond white queen comes from an old family; one of its patriarchs defied the law and brought in Mobile’s last slave ship. But she seems nice. Liberalism is in the air, la la. For the first time, the black king and queen attend the white king and queen’s investiture, and audience members pat themselves on the back for their enthusiastic reception. It brings a tear to your eye. And then the whites go upstairs to the ball and the black king and queen show themselves out.

In the telling, The Order of Myths sounds obvious, and its underlying racial politics might be. But Brown is scrutinizing the surface, the tension between individuals and their ways. You try to read their faces, and it’s as if they’re wearing Mardi Gras masks, held in place by… what? Fear? It’s no wonder. Without the order of myths, what’s left?

American Teen is the antithesis of The Order of Myths: It overtly ridicules the status quo—then reaffirms it. Maybe this will be the big crossover doc, the hit that’s a hit because it reinforces everything we knew going in. The director, Nanette Burstein, has chosen five teens in Warsaw, Indiana, to illustrate the high-school caste system and the general callousness of teens (big news—when The Breakfast Club came out). You get the geek, the nerdy (but pretty) misfit girl, the jock hobbled by parental expectations, the hunk, and the rich blonde bitch. The blonde bitch turns out to be more human than we thought—but still a bitch. Everyone else is just what they seem. The movie does get under your skin (the tremulous misfit girl, Hannah, might be a breakout role model), but the way it has been put together reminds me of those animal shows where the crew nudges the gazelles in the direction of the lions with multiple cameras standing by.

Maybe the most inapt name I’ve heard for an aesthetic movement is “mumblecore,” the tag applied to films by twentysomething white directors like Andrew Bujalski (Funny Ha Ha, Mutual Appreciation). I’m not sure who came up with the label, but the style in which these youngish characters struggle to frame their chaotic feelings has nothing to do with volume or intelligibility and everything to do with attack—or the wishy-washy lack of it. They speak up; they’re just not sure before they open their mouths what will pop out. If anything, the name should be fumblecore. Running with my new label (which popped out), I dub Baghead the first fumblecore horror movie, or what passes in the indefinite fumblecore universe for a horror movie. Directed by Jay and Mark Duplass, it’s very broad, but the satire—and its attendant babble—actually heightens the scares. The monstrous maniac with the bagged head is like an extension of the characters’ own self-indulgence.

The movie centers on four unsuccessful actors—the dweeby guy (Steve Zissis) in love with the cute girl (Greta Gerwig) who strings him along to boost her ego and keeps everything—yes—indefinite; and his more rugged pal (Ross Partridge), who has an on-again-off-again (indefinite) relationship with a longtime girlfriend (Elise Muller). After watching a bad low-budget movie, the four decide to drive out to a remote cabin to write a relationship movie for themselves—something to get them noticed and maybe (this is only implicit) help define their own mixed-up connections. After lots of alcohol, the cute girl either sees or dreams a man in the dark woods with a bag over his head. Maybe, they think, they should write a horror movie about a maniac with a bag over his head. Or maybe (it’s all very Blair Witch, indefinite) there is a maniac with a bag over his head.

Gerwig played the lead in Hannah Takes the Stairs, which turned Bujalski-type fumbling into shtick. She’s better here—a child-woman whose giddiness turns out to be self-serving. Actually, all four of these people are children; they don’t need a low-rent Jason Voorhees because they punish one another enough. Too bad the movies collapses at the end when we find out what’s really going on. Baghead is so much more vivid when it’s indefinite.

Boy A has a shocking subject and revolves around it artfully—perhaps too artfully, given the rawness of its premise. The deliberateness makes it easier to keep your guard up. The title is what the protagonist was labeled (to protect his identity) after he and a friend committed a horrific—and notorious—crime as minors. Now, at age 24, the young man (Andrew Garfield) is out, with a new name, a new home (Manchester, England), and a counselor (Peter Mullan) posing as his uncle to help him navigate his new world. The tabloids would like to know where (and who) he is; there’s also a bounty on his head. But “Jack Burridge” wants to live a normal life with true friends and a loving mate. Which is hard when he can’t share the most momentous experience of his life.

The novel by Jonathan Trigell has a punchy matter-of-factness—the kind of manly one-thing-after-another tone in which the emotion slowly bubbles up from under the surface. John Crowley’s movie has the same coolness, but it’s self-consciously stark; Jack’s Expressionistic attic bedroom (slanted wall, angled shaft of light) is a howl. Garfield gives an amazingly vivid performance that strikes me as wrong. He’s a simpleton, an innocent—more childish in his affect than the kid (Alfie Owen) who plays him in flashbacks. Boy A comes down to whether Jack is the embodiment of evil—as the tabloids portray him—or someone who did something bad but wasn’t innately bad. In the movie, it’s a nonissue; he’s sweet and befuddled. This is another of those dead-kid dramas in which the terrible event is handled like a striptease—tantalizing flashes until the climax. But when that climax comes, Boy A turns out not to be especially malevolent. He’s the child murderer as sacrificial lamb.

BACKSTORY

Prior to his 1974 WTC high-wire act, Philippe Petit was an acrobatic jack-of-all-trades who made a reputation for himself performing on the streets of Paris. Now 58, the law-abiding citizen lives just outside Woodstock, New York, and spends three hours a day maintaining his gymnastic agility by stretching, juggling, and tightrope walking. And he’s still scheming and fund-raising to engineer what could be his most amazing feat yet: crossing the Grand Canyon.

Man on Wire

Directed by James Marsh.

Discovery Films. PG-13.

The Order of Myths

Directed by Margaret Brown.

The Cinema Guild. NR.

American Teen

Directed by Nanette Burstein.

Paramount Vantage. PG-13.

Baghead

Directed by Jay and Mark Duplass.

Sony Pictures Classics. R.

Boy A

Directed by John Crowley.

The Weinstein Company. R.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.