The blistering drama Revolutionary Road has two big ideas: Suburbia suffocates the soul and Titanic sleeps with the fishes. The first idea was still subversive when Richard Yates published his novel in 1961 but is now old hat. The second, which involves transplanting the stars of a dumb but powerful romantic fantasy to the arena of domestic tragedy, is smashingly effective. Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet, the lovers whose hearts were supposed to go on, have aged into Frank and April Wheeler, and this time it’s their relationship that hits an iceberg.

It’s 1955: Frank works in a mindless job at the business-machine company that ground down his dad, and puts drunken moves on a chubby secretary; April stays home in Connecticut with two kids and cleans and stares at patios of other peoples’ houses and feels her creativity and optimism leaching out of her. In a desperate bid for sanity, she proposes they abandon their dead-end suburban lives and move to Paris and reverse roles: She’ll work, and he’ll mind the kids and tackle the artistic projects he talked about when they were young and he was king of the world. Taken aback but touched by her fervor, Frank says, “Why not?” The question is: Will this transatlantic crossing go more smoothly?

The movie is directed by Sam Mendes, the Brit who won an Oscar for another bit of suburban bashing, American Beauty. The thrust of Revolutionary Road is essentially the same, but Mendes’s first film was a broad satire with a glaze of New Age mysticism—and it was postfeminist, so the childlike husband wilted from the pressure to conform, while the castrating-bitch career-woman wife laid down the law. This film is a naturalistic chamber piece, on the other side of Betty Friedan: The woman is dying inside, while the man (also childlike—some things never change) drifts into conformity. Taking a job at his dad’s old company was meant as an ironic gesture—kind of a goof—but now the prospect of money and security is proving difficult to resist. If the novel is more surprising, it’s because Yates largely writes from the male perspective, and the way Frank goes with the flow while telling himself he still has free will (he’s hip to pop-sociology critiques of the suburbs) has more psychological zigzags than April’s mad-housewife epiphanies. Mendes—Mr. Kate Winslet—leans toward April’s point of view, so we see Frank’s vacillations through her increasingly enraged eyes.

Yet those vacillations are something to see. Unlike many child actors who’ve made the successful transition to grown-up roles, DiCaprio hasn’t evolved in predictable ways—there are no clear lines of demarcation. His boys were unusually centered, his adults unusually boyish. His wide face still carries some insulating baby-fat, like Elvis Presley’s and Bill Clinton’s (before the latest weight loss), and Mendes uses that insulation against him, sometimes cruelly: What was self-assured and spring-heeled in Titanic now looks dodgy. Mendes and Winslet push DiCaprio to places he has never been. At the height of her fury, April flays Frank, and both the character and the actor have nowhere to hide. DiCaprio loses his sure balance, his control, and has never been more vulnerable or electrifying: Winslet has forced him into the moment.

Well, she could force anyone into the moment. In Revolutionary Road, her emotions are too big for her face; she’s such an elastic actress, so in tune with her characters’ feelings, that her features seem to expand or contract in every scene. Her movements are wary, overly tight, like a woman no longer at home in her body; and when she releases that tension and moves in on DiCaprio, it’s as if she’s finally able to breathe. There is a cost to that freedom: April demolishes the marriage to survive, yet she might not be equipped to survive its demolition. There isn’t a banal moment in Winslet’s performance—not a gesture, not a word. Is Winslet now the best English-speaking film actress of her generation? I think so.

Though I’ve never been sold on Mendes’s films (the waterlogged Road to Perdition, pulp plus metaphysics, is an eye-roller), the theater work of his I’ve seen has been uniformly wonderful. Onstage, he has a grasp of design as metaphor, and every dramatic beat is on the nose (without being too on the nose). Revolutionary Road plays to his strengths. The visual set pieces, like the sea of hats emerging from the New York train station, are self-conscious, but get Mendes in a room with quick-witted actors and the crosscurrents are dizzying. The Wheelers’ neighbors (Kathryn Hahn and David Harbour) aren’t as vivid as in Yates’s novel, in which we’re privy to their thoughts, but their scenes have a distinctive weirdness, and Harbour’s mixture of the predatory and the yearning is squirm-inducing. The rhythms are organically off.

The really poetic weirdness, though, comes in a pair of encounters with Michael Shannon as John, the deinstitutionalized son of the Wheelers’ realtor (Kathy Bates), who bonds with April over her alienation. Shannon is too large for the space—Frankenstein’s monster in an ill-fitting suit whose movements (post-electroshock) are out of joint, who sees malignancy and self-deceit wherever he looks. The conception is dated: By virtue of his mental illness, John—the nut who comes to dinner—perceives truth more clearly than the “sane” characters. (Yates doesn’t go so far as to suggest, like R. D. Laing, that madness is the true sanity, but they’re in the same ballpark.) Yet there’s nothing musty about Shannon’s performance. In Bug, he played (to the hilt) a delusional paranoiac, but his John has a different vibe—acid, wires humming, ripping off other peoples’ scabs to keep from ripping into his own. His scenes are sick-comic showstoppers, but not so hilarious you can’t see what he’s doing: torpedoing what’s left of the cruise ship.

The protagonist of the leisurely romantic fable The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is born old and wrinkled and ages backward, which means we spend an hour and a half waiting eagerly for Brad Pitt to look like Brad Pitt—i.e., superhumanly pretty—and the next hour and change thinking, Is that all there is? Not much goes on in that face, and Pitt’s resemblance to Robert Redford—pouchy cheeks, quizzical half-open mouth—tends to underscore what’s absent. Redford in his prime was alert and prickly, perpetually dissatisfied, whereas Pitt exudes complacency. As Benjamin, whose heavily symbolic malady has something to do with a supernatural clock designed by a grieving father to move in reverse, he gives you no hint what his character makes of the changes. He doesn’t bring out the tension between mind and body; he just stares ahead with sad eyes and lets his makeup do the acting. Pitt isn’t bad (his noncommittal performance might even appeal to some people, who can project on him what they will), but he lets opportunities slide that other, physically inventive performers would kill for.

The movie, directed by David Fincher, will probably be a hit anyway, because the gimmick (adapted by Eric Roth from an F. Scott Fitzgerald story) is fun to play around with in your head, and because it’s liberating to watch makeup gradually come off an actor instead of getting thicker (and phonier). Fitzgerald spent the later years of his life haunted by the profligacy of his early ones; to reverse time and recover his youthful body and stamina but retain his aged wisdom must have been a blessed pipe dream. Fincher is no humanist (his most vivid film is the clammy, clinical Se7en), and he refrains from milking the material for sentiment—which means the movie isn’t mawkish, but it isn’t especially vivid either. The light is yellowish and diffuse, the backdrops—the clock, a factory wall, the side of a ship—oversize. It’s a gentle expressionism, redolent of death without rattling bones.

Fitzgerald’s alter-ego finds his Zelda—called, aptly enough, Daisy—when she visits the convalescent home where his horrified father abandoned him. She grows up to be Cate Blanchett, whose face is uncannily ivory-smooth. When Daisy and Benjamin meet in the middle, both at the peak of their physical perfection, they’re like two Greek statues basking in each other’s radiance, albeit with dialogue that knocks them down a few pegs: “I was thinkin’ that nothing lasts, and what a shame that is.” As they move toward death, one in the direction of infancy and dirty diapers and the other toward old age and osteoporosis, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button attains a level of quiet grace. It’s too bad that I can barely remember the movie after only a week. Nothing lasts, indeed.

The remake of that fine old fifties alien-invasion picture The Day the Earth Stood Still—a peacenik rejoinder to all the sci-fi movies in which E.T.’s stood in for soul-sapping Commies—comes to a standstill about an hour before the Earth does in the wilds of New Jersey. Trust me, folks, Jersey turns out to be the ultimate momentum killer: The main characters, among them “renowned scientist” Dr. Helen Benson (Jennifer Connelly) and an alien, Klaatu (Keanu Reeves), speed toward the Lincoln Tunnel—and yet, as in a bad dream, the tunnel seems to get farther and farther away. Just when we think they’re going to make it, they pull into a McDonald’s. Then they take a detour to talk philosophy with Professor Barnhardt (John Cleese), who lives deep in the Jersey woods. Meanwhile, the excellent-looking giant robot Gort, seemingly on the brink of going Godzilla on Manhattan, transforms into an unphotogenic swarm of CGI bugs and annihilates Giants Stadium. Atop their tanks in the city, members of various government forces look at their watches and noisily exhale.

Klaatu is a dream role for the beautifully blank Reeves, since he doesn’t even have to pretend to emote. Versed in the writing of Malcolm Gladwell, he announces that humans will have to be destroyed because Earth has reached the tipping point, although it isn’t clear if he means war, global warming, or the ascendancy of snark. “You treat the world as you treat each other,” he says. “We can change,” pleads Dr. Helen. Despite being shot, shelled, and chased into New Jersey, Klaatu believes her, perhaps because he knows that Obama will soon be president. As he walked to his spaceship, I had an overwhelming urge to call out: “Klaatu, Keanu. Keanu, Klaatu. Klaatu, Obama. Obama, Klaatu. Oprah, Keanu, Klaatu … ”

John Patrick Shanley’s film of his every-award-under-God-winning play Doubt is a heavy slab of dramaturgy, dark-toned and somber, yet intense as hell. Even opened up for the screen, with air and trees and extra kids and nuns, it has a primal theatrical compression: One confrontation forces the next, backs are driven against walls, no points of view overlap. Big stuff is packed into small rooms with the roofs ready to explode.

It’s 1964, and Father Flynn (Philip Seymour Hoffman) delivers a sermon to his congregation and the schoolboys in his charge asserting that doubt can be as sustaining as certainty, and few understand what he’s on about—least of all this Catholic school’s severe principal, Sister Aloysius Beauvier (Meryl Streep), who strides among the pews and classrooms watching for signs of disobedience. Wherefore, she wonders, this liberalism? There must be a sinister motive. A fresh-faced, hopeful nun, Sister James (Amy Adams), notices Father Flynn paying special attention to Donald (Joseph Foster II), the school’s sole—and very vulnerable—African-American student, who returns from a private meeting with the priest looking shaken. No … It couldn’t be … Yet she has a duty: Sister Aloysius must be told.

Whose voice is coming out of Streep? It’s working-class Queens, pinched and nasal: Edith Bunker? Among these naturalistic actors, the accent is distracting, and so is the ever-pursed mouth. Yet Streep is riveting. She shows that Aloysius, however monolithic her exterior, is alive on the inside. The eyes dart about, and the musings under her breath—sighs, asides, exclamations—suggest an openness to the notion of human imperfectibility. Her interrogations of Hoffman’s Flynn are seesaws of power. You can see his inner schism, of which he’s oblivious: generosity (the boy needs a father figure) side by side with entitlement. He has what Aloysius doesn’t: the privilege of patriarchy. Hoffman has a tendency to stress the grotesqueness of his characters, an instinct (possibly self-hating, yet sadistic toward the audience) he mistakes for integrity. His Father Flynn is one of his best performances because, all in all, he’s warm and likable. He doesn’t believe he’s a predator, so we can’t quite either. We understand why Sister James wants to see the good in his motives, and Amy Adams, with her cute little overbite that seems an extension of her eagerness, makes James’s struggle to shine extremely touching.

There is a fourth major performance, brief but breathtaking: Viola Davis as Donald’s mother. For many reasons, Mrs. Miller’s son has not been at home in his world, and the stairs to the next level keep getting knocked out from under him. Davis shows you a woman who, in her desperation, has moved beyond conventional morality, who has become single-minded for the sake of what she sees as her boy’s very survival. The position at first appears unconscionable bordering on actionable. But in the end, it’s her view that makes our hearts bleed.

Roger Deakins’s cinematography could hardly be crisper, more focused. There is no escaping the starkness of this universe: the white flesh, the deep blacks of the nuns’ garb, the gray skies, the brown leaves kicked up by winds. To underline the spiritual discombobulation, Shanley cuts from formal, symmetrical compositions to sudden, slanted ones. It is all, on one level, overdone, and there’s a touch—a lightbulb that explodes at especially fraught moments, as if overloaded by electrified synapses—that might be pushing it. In adapting his play, Shanley makes one serious mistake: Having introduced Donald as a character, he should have written a new scene in which the boy is questioned—especially since Joseph Foster makes such a deep impression in his few moments on-camera, with waves of neediness coming out of that small frame. But Doubt is still overpowering; it took me a while when it was over to stop shaking. It’s the dramatist’s business to sow doubt, to set down points of view that can’t be reconciled, and Shanley makes visceral the notion that one can be right but never absolutely right, that doubt might be our last, best hope.

For two decades, Clint Eastwood has shrewdly resisted making one more Dirty Harry movie: Another cartoon vigilante picture wouldn’t fit in with his Golden Years status as an American Master who continues to evolve, revising his old meathead-genre tropes in ways that compel some auteurists to invoke the names of Dante and Shakespeare. But Gran Torino is his final Dirty Harry movie manqué. His hero, Walt, is the same Cro-Magnon right-wing vigilante racist, but this time, like Prospero in The Tempest, the old man is poised to abjure his magic (his magic Magnum) for the sake of the greater good. The movie is ludicrous, but Eastwood’s consistency is poignant. He has an agenda and sticks to it.

He ought to have let someone else direct him, though—his acting is all over the map. At his finest, he delivers thesis lines, the ones about how terrible it is to kill a man—as Walt did in Korea—with the subtle but insistent quaver of a great jazz musician filling a measure to bursting: His day wasn’t made after all. But most of his readings would be too broad for even the movies he made with farting orangutans. From his porch, Walt surveys the big family of Asian-Americans (Hmong) who live next door, and Eastwood twists up his mouth and growls that all the real Americans have moved away and hocks a goober on the lawn. “Grrrrr … goddamned slopes … hwick-pitooey.” He upstages Walt’s dog, who is mostly quiet.

The script, by Nick Schenk, requires the just-widowed Walt to discover a new—and better—family in those “slopes,” to commit to them in ways he could never commit to his sons or overly entitled grandkids. So he teaches the boy (Bee Vang) to swear, hurl racial expletives, and pick up pretty girls. He gives him manly discipline. (“You know something, kid? You’re all right.”) And he lets his softer side come out under the probing of the boy’s sassy sister (Ahney Her). Amid the culture-clash jokes, a higher symbolism creeps in. When the family is imperiled by an Asian gang, Walt responds in his macho-vigilante way—then seems to realize that, as with the Vietnamese and Cambodians and Laotians the Americans supposedly fought for, he has made their lives even more violent.

The problem is that for all Eastwood’s twilight-of-life ambivalence about his own mythical persona, his is still a paranoid universe of predators and the preyed-upon, so there’s never a need for distracting shades of gray or the kind of every-man-has-his-reasons drama in every episode of The Wire. These are simpleminded moral dilemmas, and the scenes with the Asian gang are almost as crude as anything in Sudden Impact. To think Gran Torino is a masterpiece, you have to accept the contrived setups and sledgehammer melodrama. You have to grade the movie on that same meathead-vigilante curve. As Harry once said, “Man’s got to know his limitations,” and Eastwood has a gift for making his look like brave artistic choices.

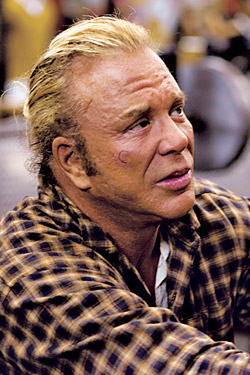

Darren Aronofsky is our most brilliantly druggy filmmaker: His syntax transforms to match his characters’ feverish perceptions—to pull you into their radically altered states. The nature of the drug is different in every movie: swirling and fractured in Pi, transcendentally romantic in The Fountain. In his new film, The Wrestler, he induces a state of masochistic ecstasy—the oneness with the universe that comes from being pummeled and cut and watching one’s blood fly onto the canvas. The tragic hero is Randy “the Ram” Robinson (Mickey Rourke), an aging pro-wrestler, once a star, with nothing real in his life but that Artaudian Theater of Cruelty in which men in mythically garish costumes perform brutal ballets before shrieking crowds. Beside Aronofsky’s bouts, the ones in Raging Bull seem like Japanese tea ceremonies. No matter how choreographed, the pounding is ferocious, and we see the world through Randy’s swimming perceptions. Even cringing, we feel his joy. He secretes a small razor in his costume and, down for the count, slices open his face to make the gore even splashier. We rise with him in triumph: I bleed, therefore I am.

The movie isn’t as world-shattering as those bouts: It’s a regretful-old-warrior weeper, in which God’s loneliest man attempts to reconcile with the bitter child (Evan Rachel Wood) he abandoned and reaches out to the only woman who shows him affection—a stripper (the ever-comely Marisa Tomei) who has the grace not to let him see her eyes wander in search of other lap-dance customers. We know that even if he touches the stripper’s heart and breaks through his daughter’s anger, he’ll screw it up because, after all, he’s only good for one thing in life, even if it kills him. Allusions to Christ are everywhere; the stripper talks about the carnage in The Passion of the Christ. Is Aronofsky being tongue in cheek? I don’t think he’s ever tongue in cheek.

This is a case where an actor makes the difference. Mickey Rourke was once among our most charismatic leading men: alert, wittily self-contained (he always seemed to be smiling at a private joke), with a high but seductive voice. Whatever the hell he did to himself, it worked for Sin City, in which the makeup for his monster-man avenger Marv brought out the freakish poetry in his distended physiognomy. In The Wrestler, his face has that poetry without the makeup. Rourke has long blond hair that makes him look like a battered lion, and his tight, swollen mask makes Randy’s struggle to bare his soul even more momentous. It’s dumb, it’s outlandish, but smashing other people’s heads and getting his own smashed back really does complete him.

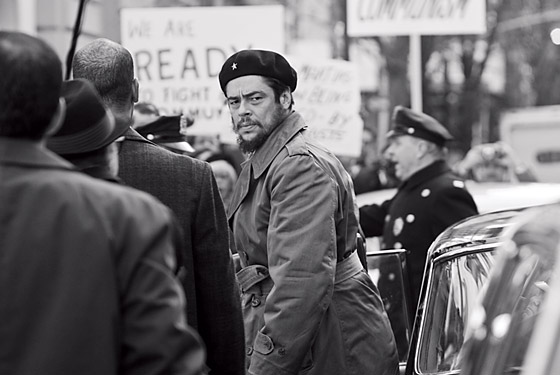

Che, which runs about four and a half hours, chronicles the two big revolutionary battles in the life of Che Guevara (Benicio Del Toro): Part One is Cuba (cigars for everybody), Part Two Bolivia (last cigars for everybody). As movie directors go, Steven Soderbergh is an intellectual, which means that when he has a brainy conception for a film, he has a hard time letting it go—or ringing variations on it, testing it. His notion here is to show you temporally, tactilely, how grueling it is to slog through a jungle and violently overthrow an unjust government; for Che it was even harder because (a) he had terrible asthma, and (b) he insisted on toting books with him to teach his soldiers (who had to be literate) about the historic struggles of the proletariat. Che is an impressive physical feat, but especially in the second part, which gives you day after day of rebels being killed and indigenous poor people not joining the good fight, you start to look forward to Che getting riddled by bullets. The whole movie is a forced march.

In The Reader, Kate Winslet plays Hanna Schmitz, a glum, buttoned-down German with a dark secret, which we know has significance because the protagonist, Michael (David Kross when young, Ralph Fiennes when middle-aged), has a teacher who lectures, “The notion of secrecy is central to Western literature.” The Reader comes with its own reader’s guide. Michael loses his virginity to Hanna anyway, although he should probably have guessed that it wouldn’t end well when, in the course of peeling off her stockings, she gives him a hard stare and asks, “Haff you always been weak?” Nazi ideals die hard. Michael’s face signals hurt, there are sad piano chords, he turns away, then Hanna’s face reveals that she knows she has been cruel. The director, Stephen Daldry, has radar for the obvious, which he imparts to his actors. Hanna insists that Michael read to her before their couplings, but the pall is so heavy that neither the reading nor the sex looks like much fun. In the movie’s second half, Michael tries to understand how not-bad people can do very bad things and whether learning to read can make a difference. It appears that the filmmakers have taken Hannah Arendt’s notion of the “banality of evil” way too literally.

John Leguizamo gives his truest performance on film as a failed boxer in Salvatore Stabile’s emotional roller-coaster Where God Left His Shoes. Axed from the card of an upcoming bout, he loses his apartment and goes with his wife (Leonor Varela) and two children (David Castro, Samantha Rose) into a homeless shelter. The film follows his frantic efforts to get them out of there by Christmas, which involves fast-talking and then pleading with housing directors and a series of potential employers while his belittled son traipses around the city after him. The acting, the on-the-fly atmosphere (the film was shot quickly), and Leguizamo’s increasingly urgent hustle are deeply evocative, but parts of the movie are almost too painful to endure. Like The Pursuit of Happyness—but with a vastly different ending—the film taps into the primal fear of not being able to protect one’s family from the cruelty of the world. Given these times, it’s almost too big a dose—it gives your bad dreams bad dreams.

Revolutionary Road

Directed by Sam Mendes.

Paramount Vantage. R.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

Directed by David Fincher.

Paramount Pictures. PG-13.

The Day the Earth Stood Still

Directed by Scott Derrickson.

Twentieth Century Fox. PG-13.

Doubt

Directed by John Patrick Shanley.

Miramax Films. PG-13.

Gran Torino

Directed by Clint Eastwood.

Warner Bros. Pictures. R.

The Wrestler

Directed by Darren Aronofsky. Fox Searchlight Pictures. R.

Che

Directed by Steven Soderbergh.

IFC Films. NR.

The Reader

Directed by Stephen Daldry.

The Weinstein Company. R.

Where God Left His Shoes

Directed by Salvatore Stabile.

IFC Films. NR.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.