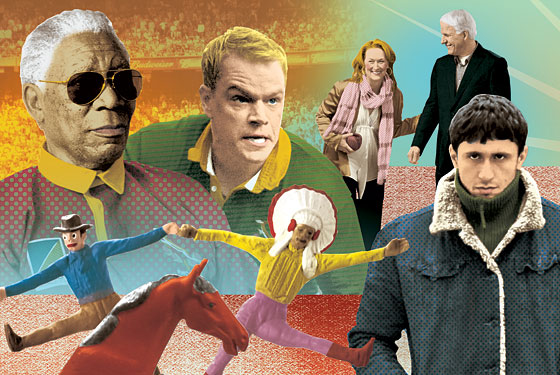

The Nelson Mandela drama Invictus, directed by Clint Eastwood, centers on a true act of political symbolism that went a long way—as national sporting events can, like it or not—toward uniting a divided, potentially explosive South Africa. After his election in 1994, Mandela resisted pressure from his party to wipe out Afrikaners’ cultural institutions along with their vile system of apartheid. He not only preserved the white-run Springboks rugby team (loathed by blacks, who routinely cheered for other countries), he reached out as an ally to the captain, François Pienaar. He attended their championship match against New Zealand wearing the hated green-and-gold colors. And his instincts proved to be dead-on: Mandela helped whites save face, and they in turn began to trust—and admire—him.

Since Mandela is the closest thing to a saint we’ve seen in the last quarter-century, it seems churlish to complain that Invictus is a hagiography. It seems less churlish to complain that there isn’t a surprising note in its 134 minutes—not a line, not an image, not a performance. Eastwood directs as if he’s looking beyond the Oscar to the Nobel Peace Prize—an impressive about-face for a man who once celebrated the U.S.’s trampling of tiny Grenada and who ran for mayor of Carmel, California, as a property-rights conservative, likening an ordinance regulating second kitchens to “Adolf Hitler knocking on your door.” But Eastwood connects with this story on one crucial level: He understands the value of symbolism. Last year, in Gran Torino, he essentially killed off his vigilante icon Dirty Harry in the name of social harmony. Now he does a persuasive job underlining the character of a man whose turn away from arguably righteous vengeance set an example that will outlive us all.

As Mandela, Morgan Freeman transforms his face into an ancient yet childlike mask and speaks in exquisitely measured tones. You can appreciate Freeman’s attempt to convey Mandela’s simplicity—the product of enormous complexity, endless contemplation, and unimaginable suffering—and still get the feeling you’re watching a great actor neuter himself. Matt Damon does fine as Pienaar, donating his stardom to the cause. A scene in which Pienaar visits the tiny cell where Mandela spent three decades is one of the film’s quiet high points—underlined by Freeman’s recitation of the poem that gave the film its title: “My head is bloody but unbowed … I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.”

Eastwood is most in his element when following Mandela’s security team, an uneasy but increasingly firm alliance of blacks and the whites who used to beat, imprison, and kill them. But he makes a hash of the championship rugby match; it’s so choppy that you only know the Springboks have scored because he cuts to a cheering Mandela. Invictus doesn’t acknowledge the irony of that final match—that Mandela is rooting for Afrikaners against a team that included Maoris, a native people who had to overcome their own form of apartheid.

One aspect of Invictus is sadly relevant to our present situation. Barack Obama, who reveres Mandela, came into office thinking he could inspire the same kind of unity, only to be stymied by the opposition’s cynical and corrupt intransigence. Could even Mandela have overcome the likes of Rush Limbaugh, Karl Rove and Dick Cheney?

One of the worst pieces of casting in cinema history was when Milos Forman gave Colin Firth his big break as the title character in Valmont, an aristocrat who treated seduction with the steely logic of a military commander and could slip into any role required by the current object of his attention. That’s not Firth. In his best parts, he is too ill at ease to lie—he radiates an integrity born of discomfort. Embarrassed at revealing too much, he’s apt to retreat into a prickly formality, which made him the definitive Darcy not once (in the BBC’s Pride and Prejudice), but twice (as Darcy’s spiritual heir in Bridget Jones’s Diary). In A Single Man, based on Christopher Isherwood’s novel, Firth goes deeper into his emotional rabbit hole and is even more expressive. He plays George, an aging gay professor whose lover of sixteen years has been killed and who is unable—this is 1962, when there’s little tolerance for homosexuality—to reconcile his private and public selves. George is forbidden to grieve openly, so his face remains tight. Yet the rigidity of his head, the way he turns to acknowledge others a beat too late, the way he moves as if underwater, suggest momentous forces below the surface. Fear of an unmasking makes every word or gesture seem false—not to us, but to George, who looks on himself with disgust, appalled at his cowardice. Narrating from inside his head, with a minimum of motion, Firth gives the performance of the year.

The movie itself is a good try, but it’s not on Firth’s level. The fashion designer Tom Ford directed from a script he wrote with David Scearce, and Ford doesn’t seem to trust his new medium’s dynamism. He drains the color from his protagonist’s stricken present and intensifies it for flashbacks and rare moments of connection. He tries to create tension between the pristine early-sixties surfaces and George’s convulsive inner world. But many of the images feel overplanned, congealed. George’s house is far too opulent for a man on his salary, and the pinkish skies and slow-motion exhalations of tobacco smoke don’t have much to do with George’s point of view. Isherwood made George and his dead lover, Jim, roughly the same age, but Ford has cast Matthew Goode (seen in flashbacks), who looks a quarter-century younger and would barely have hit puberty when the couple came together. As George’s lone confidante, an alcoholic divorcée called Charley, Julianne Moore affects another of her self-conscious English accents, and Ford doesn’t know enough to protect her from looking more affected than her character. Given the awkward staging, A Single Man might make you long, perversely, for George to stay single—anything to watch Firth stare into the mirror, searching for the self behind his eye.

Given that Alice Sebold’s novel The Lovely Bones opens with the rape and murder of a 14-year-old girl, maybe it’s a blessing that Peter Jackson’s film is too ham-handed to get under your skin. But sitting through it is still an ordeal. As in the book, the narrator is the dead girl, Susie Salmon, played by Saoirse Ronan with pale, iridescent eyes. Susie recounts the story of her murder—if she’s raped here, it isn’t mentioned—by a serial killer, Mr. Harvey (Stanley Tucci), who happens to live in her neighborhood. Semi-transparent, she watches her parents (Mark Wahlberg and Rachel Weisz) react to her disappearance and the discovery of blood—no body—in a pit. She eavesdrops on the boy she had a crush on, her younger sister, and even her killer. Halfway between worlds, she moves in a limbo, sometimes romping with another dead girl through a surreal, computer-generated never-never land.

It’s no mystery how Sebold arrived at her premise. In a memoir, Lucky, she revealed that she was raped in college, and that the police said she was “lucky” because the last woman raped there was killed. The Lovely Bones is a fantasy of the death she didn’t have, its limbo likely a metaphor for her post-rape detachment from her body, its fantasy landscape connected to the otherworldly lightness induced by a turn (for a brief spell) to heroin. For The Lovely Bones to work onscreen, it would need a filmmaker who could blur the line between literal and metaphorical—like Lynne Ramsay, who made the semi-abstract Morvern Callar and was briefly attached to write and direct The Lovely Bones before it was even published. Jackson’s demarcations between life and limbo are the opposite of fluid. The fantasy sections are like an illustrated New Age storybook for 6-year-olds, with Saoirse and her blue peepers used for mystical sentimentality.

Never particularly original, Jackson can only replicate the language of other movies: a bit of Hitchcock here, a little Spielberg there, and none of the borrowings apt. The actors are all over the place. Tucci, with his caterpillar mustache and finicky comb-over, is so floridly creepy he might as well have child molester tattooed on his forehead. You can snicker at how over-the-top everything is, but it feels weird to be laughing at a film filled with ghastly images of dead girls. With material this disturbing comes a special responsibility. Jackson’s ineptitude isn’t just disastrous—it’s sinful.

As I watched the star-stuffed screen version of the musical Nine, I had a tough time getting past the central conceptual boo-boo. Let me explain. The musical’s evolution began with Fellini’s 8½, the mother of all self-referential, blocked-artist movie masterpieces, in which a pampered Italian auteur has phantasmagorical visions of various lovers (and his dead but still formidable mama) while he juggles producers, wives, mistresses, starlets, journalists, etc., and labors to generate a script for his new epic. Studded with songs and dances, its title bumped up by half a numeral, Fellini’s cinematic tour de force became a Broadway tour de force for Tommy Tune, whose circusy staging blurred past and present, artifice and reality.

In the film directed by Rob Marshall, Italian director Guido (Daniel Day-Lewis) has visions of the women in his life—on a stage. That’s right: This film about the visions of a visionary film director moves back and forth between life and a theater in which women in lingerie are carefully arranged around a multileveled set. With all the possibilities for Fellini-esque montage, for explosive dances in real settings, for cinema, Marshall maroons us in one big room, editing the numbers so maladroitly you can’t even savor their theatricality.

Not that there’s much in the way of dancing—it’s mostly hip-swinging and derrière-wriggling and sultry posing. Marshall has regressed from the middling heights of Chicago, where the choppy editing was at least in sync with the music’s staccato oomph. Maury Yeston’s lyrics banalize the characters’ emotions and tell us nothing we don’t already know (“My husband, he goes a little crazy making movies …), but at least they’re well sung. Yes, the voices are surprisingly on-key and sound better than they probably are coming out of those gorgeous faces. Kate Hudson croons and sashays, Penélope Cruz spits out her words and slithers, Nicole Kidman … well, her face doesn’t budge but she does hit the notes. As the bear-woman of the beach who introduces young Guido to the highs of low flesh, Fergie pops out of the screen with 3-D boobs and a flicking tongue. We know from Marion Cotillard’s performance in La Vie En Rose that she can sing—but not that she could look so irresistibly demure while doing so. Dame Judi Dench has enough dry wit to survive a horrible number about the Folies Bergère. There is also an Italian woman going by the name of “Sophia Loren,” but I prefer to think it’s someone wearing a mask. Day-Lewis holds the ramshackle proceedings together. He doesn’t dance, but he’s light on his feet, fluid as Chaplin, and his long, stringy body in that dark suit and skinny tie makes him less a Guido than a Linguido.

The Romanian drama Police, Adjective is a deadpan morality play in which a cop (Dragos Bucur) is ordered to tail a high-school kid who turns out to be doing nothing illegal except smoking a little dope. The cop argues that there’s nothing to the case, that it’s the informant who should be investigated. But he gets nowhere with his superiors, who insist his definition of conscience is limited. The second feature by Corneliu Porumboiu (12:08 East of Bucharest) won a Cannes jury prize and raves at this year’s New York Film Festival. I wonder if critics were writing those reviews during the scenes in which the cop walks up and down, up and down, staring ahead, waiting, for three, four, ten minutes. Or maybe it’s the scene when he leafs through a magazine while waiting to see his boss … ticktock, ticktock. Porumboiu means to evoke the absurd, suffocating power of a police state. But the projectionist could double the movie’s speed and it would still drag.

Scott Cooper’s Crazy Heart is a grand pedestal for Jeff Bridges as a bloated, washed-up boozehound country-and-western singer called “Bad” Blake. What makes the performance such a beauty is the contrast between Bad when he’s onstage and off. In his cups, he staggers around seedy venues, top-heavy and reeling; but when he slings his guitar around his neck, he leans back so that its weight literally centers him. His music centers him, too. He sings like he’s making his last stand against the universe. Bad’s songs, written by T-Bone Burnett, have an authentic drive: They’re all that’s left of his life. At least they’re all that’s left until he meets a journalist and single mom played by Maggie Gyllenhaal, who he thinks could be wife No. 5. Why she thinks the same for even a millisecond is one of the movie’s more movie-ish conceits, but Gyllenhaal has such a delectable spaciness that you almost believe she sees something we don’t. The movie turns out to be another ode to the healing powers of AA (Robert Duvall co-produced—or maybe his Tender Mercies character did), and the final scene is a cornball stinker. But there’s a grounded and shockingly credible turn by Colin Farrell as a Toby Keith–like superstar who throws Bad a lifeline—and the way Bridges looks at it, with both rage and relief and then rage at his own relief, would make a great C&W song.

Nancy Meyers’s comedies make me feel like someone put itching powder down my shirt—but that’s partly, I admit, the result of envy. Her characters are absurdly affluent and never seem to think about money, and I get the feeling Meyers doesn’t, either, since she never uses their disconnect from the other 99.999 percent of the world satirically, the way Preston Sturges or Paul Mazursky did. It’s Complicated is the most accomplished but also the least self-aware of her films. On the surface, it’s about the mixed-up feelings of a long-divorced couple, Jane (Meryl Streep) and Jake (Alec Baldwin), when they get drunk and have smashing sex on the eve of their son’s college graduation—after which Jake begins to show up on her doorstep panting for nookie. A successful caterer and gourmet-market owner, Jane is, on one level, thrilled, since Jake had abandoned her for a slinky young woman. But suddenly she has another suitor: Adam (Steve Martin), a sweet, divorced architect designing an extension for her (already huge) house. What to do, what to do? Turns out It’s Complicated is not so complicated after all. It’s an older woman’s emasculating revenge fantasy. Meyers lingers on Jake’s girth, the bitchiness of his young wife, and his humiliating infertility, while Jane grows more radiant with each scene. Adam, meanwhile, is a dear. The nice thing about Martin is that he’s so smooth and white and shy that you can project whatever you like on him. Here he is mostly soulfully morose. (I get the feeling it’s his natural temperament.) Baldwin comes on like a rocket but plays the same scene over and over and finally runs out of invention.

It’s Complicated is a celebration of Streep—normally the queen of artifice—as a Natural Woman. And buoyed by her worshipful co-stars, she does look like she’s having a ball. It’s not that ghastly giddiness of Mamma Mia! but something deeper. I think this is the first time onscreen that Streep—famously insecure about her looks—has truly felt beautiful.

The Belgian animated feature, A Town Called Panic, plays as if one day its directors, Stéphane Aubier and Vincent Patar, smoked very strong hashish and stumbled on a chest of old plastic toys—a little cowboy and an Indian in a headdress, a horse, some cows and pigs and a farmer (and his wife), and piles of other bric-a-brac—and free-associated a demented scenario against cutout scenery about roommates Cowboy and Indian wanting 50 bricks for a barbecue for Horse’s birthday and accidentally ordering 50 million and wrecking their house and rebuilding it but having the walls stolen every night by sea creatures and chasing them underwater and getting captured by mad scientists and on and on ad absurdum … and hilarium. The blurty voices and jerky animation recall South Park (which I mean as a high compliment), but the film has a transcendent silliness all its own. Kids might not go for it; all the subtitled French babble could be bewildering. The rest of us will want whatever Aubier and Patar were smoking.

For a royal biopic, The Young Victoria is fleet, modest, and unfussy, which makes it hardly the sort of grandiose wallow that fans of stuffed turkeys like Elizabeth go in for. But the rapport between Emily Blunt as the pre-coronation Victoria and Rupert Friend as her German suitor Albert is witty and mischievous and transporting. They have a meeting of minds, with bodies to follow (in time). With her genuinely poetic beauty—her long neck, cleft chin, and faraway blue eyes—Blunt requires no suspension of disbelief to be taken for a queen. It’s everyone else that’s a stretch.

Invictus

Directed by Clint Eastwood.

Warner Brothers Pictures. PG-13.

A Single Man

Directed by Tom Ford.

The Weinstein Company. R.

The Lovely Bones

Directed by Peter Jackson.

Paramount Pictures. PG-13.

Nine

Directed by Rob Marshall.

The Weinstein Company. PG-13.

Police, Adjective

Directed by Corneliu Porumboiu.

IFC Cilms. NA.

Crazy Heart

Directed by Scott Cooper.

Fox Searchlight Pictures. R.

It’s Complicated

Directed by Nancy Meyers.

Universal Pics. R.

A Town Called Panic

Directed by Stéphane Aubier and Vincent Patar.

Zeitgeist Films. NR.

The Young Victoria

Directed by Jean-Marc Vallée.

Apparition. PG.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.