Clint Eastwood’s supernatural drama Hereafter starts big and ends small, its hold gradually slackening, its thread dissolving. To be honest, it never had much of a thread. The film introduces three main characters in three different countries, cutting among them more or less at random, laying the groundwork for what we hope will be a killer last act in which they all come together and … what? Cross over to the “other side”? Welcome the dead in a Close Encounters mother ship? No, it’s not that kind of movie. Hereafter occupies some muzzy twilight zone, too woo-woo sentimental to be real, too limp to make for even a halfway decent ghost story.

The picture has one indisputably boffo scene, and it comes at the start: A tsunami smashes into a Southeast Asian beach resort, sweeping through the town and carrying off (among many others) a French TV reporter, Marie (Cécile de France), who gets conked on the head and appears to die. It’s an amazing piece of filmmaking, and not just because of the special effects. Eastwood’s camera remains at street level, watching the wave as it rushes closer and closer, getting picked up and carried along with Marie. The sequence is such a tour de force that it’s heartbreaking when Marie—who’s not dead but not not-dead—has a vision of the afterlife that looks like the old TV promos for Lost, with actors (in this case all streaky and whited-out) at various distances staring into the camera. It gets so tacky so fast.

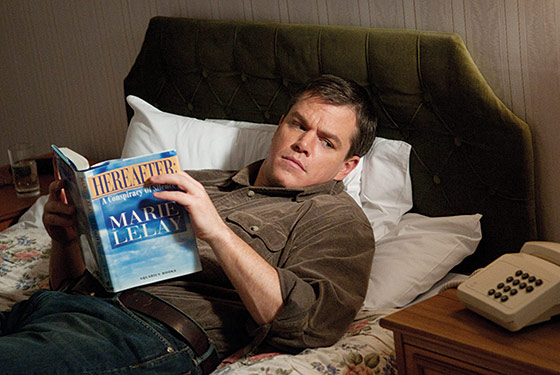

In San Francisco, meanwhile, Matt Damon’s George abandons a lucrative career as a John Edward–style medium because he can’t handle the pressure that comes with being a conduit to the hereafter. Although he sounds like a typically bogus cold reader—“I’m seeing a woman with dark hair: Is that right?”—he’s supposed to be the real McCoy, a man who can grasp someone’s hand and see … those blurry Lost promos.

The final protagonist is Marcus (played by both George and Frankie McLaren), a working-class London boy whose twin brother, Jason (also played by George and Frankie—a curious casting gimmick that pays off), gets chased by bullies into the street and run over by a car. Snatched away from his junkie mom and placed in foster care, the bereft Marcus, who always let Jason make the decisions, Googles in anguish for someone to help him talk to his brother, preferably on a daily basis. A couple of clicks and there’s George.

Peter Morgan (The Queen, Frost/Nixon) said he wrote Hereafter after losing a close friend and longing—as we all do, at some point—to make contact with “the other side.” That, of course, is how unscrupulous charlatans earn seven-figure incomes. But while Morgan is careful to show us some phonies—cold readers asking questions that are bound to elicit “hits”—he’s firmly in the camp that says, “Hey, it’s possible.” Given that early in the film, the existence of an afterlife is firmly established and George’s powers are proved authentic, there’s little left for the movie to do but bring him and Marcus and Marie (now also plagued by Lost promos) together. And that’s exactly what happens—in about an hour.

As usual with Eastwood, the performances are all over the map. Damon is so self-effacing you can almost see Eastwood’s visage superimposed over his, the mole supernaturally shifted from the right side to the left. A long section of the film centers on George and an effusive young woman he meets in an Italian cooking class, which is meant to show how his links to the dead inevitably sabotage his connection with the living. But watching Bryce Dallas Howard madly overact—she looks like she wants to ravish him over his cutting board—while Damon stares at her in a semi-stupor, you wonder if the scene is meant to be played as farce. The final scene, in which George is suddenly able to see the future as well as the dead, is just plain bewildering.

My impression is that Eastwood—while revered by many as a premier auteur with a strong personal vision—picks scripts he likes and shoots them pretty much as they are; and when a script is, like Morgan’s, badly in need of a polish and minus a satisfying windup, he’ll shoot it anyway and figure the lapses will be viewed as powerful artistic choices attributable to his laid-back, jazz-inflected style. That seems to be the case with Hereafter, which closed the New York Film Festival and has already been hailed as a masterly summing-up of his long career—although what Morgan’s first-draft stab at a crossing-over weepie has to do with the rest of Eastwood’s oeuvre is a mystery as unfathomable as what happens after death.

Billed as “two decades in the life of a notorious terrorist,” Olivier Assayas’s Carlos is five and a half hours of border-hopping, bombings, botched attacks, a brutal but bungled hijacking, and many, many short scenes in which bearded men and beautiful, impassive women sit in small rooms and strategize how best to advance the Palestinian cause and defeat the imperialist capitalist world order. In retrospect, it’s a bit of a blur, and you might opt to see Assayas’s condensed version (alternating in some theaters), which clocks in at a trim two and a half hours. I say go for the whole shebang. Shot by shot, scene by scene, it’s a fluid and enthralling piece of work. I wasn’t bored for a millisecond.

As Carlos “the Jackal,” born Ilich (after Lenin) Ramírez Sánchez in Venezuela, Édgar Ramírez gives a strange but magnetic performance, disarmingly deliberate for a terrorist who exulted in his own celebrity. Ramírez shows us a man so certain of his course that he doesn’t need to emote. Early on, he tells a movement leader that his weapons are an extension of his body and admires his naked self in a mirror. Later, he’ll gain weight and find a growth on his testicle and have liposuction for his love handles—but by then he’ll be a liability to the movement, a casualty of his notoriety, a man without a country.

Both in flashy globe-trotting thrillers like Demonlover and in melancholy meditations on impermanence like Summer Hours, Assayas returns to this theme: the unbearable lightness of internationalism. Speaking many languages, moving from Germany to France to Hungary to Yemen to Syria, Carlos ends up homeless and friendless. The government that protects him today will try to assassinate him tomorrow. He’s paralyzed long before he’s imprisoned. Assayas has become such a graceful filmmaker that you don’t actually see Carlos’s world shrinking. You just realize, all of a sudden, that all the doors are closed and the boarding gates barred.

Hereafter

Warner Bros. Pictures.

PG-13.

Carlos

IFC Films. NR.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.