David Edelstein: Do you want the true-true? I think the film of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas is dumb-dumb. Andy and Lana Wachowski (the latter once Larry, and his transformation into Lana might well tie into the notion expressed in this film that physical boundaries are made to be transcended) and Tom Tykwer have seized hold of Mitchell’s literary tour de force, passed it through the Benihana chopper, and extruded the most jaw-droppingly woo-woo piece of sci-fi romantic drivel since The Fountain.

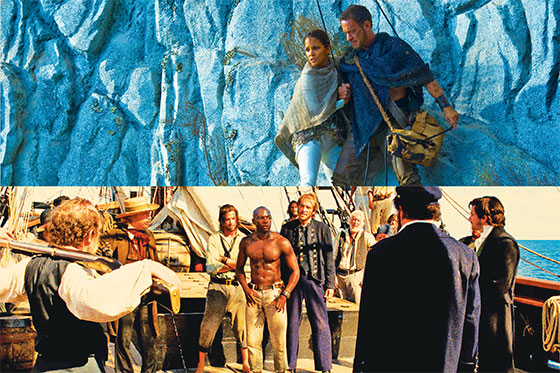

I’ll leave it to you, Kathryn, to enumerate Mitchell’s accomplishments on paper, but one thing I loved about the novel was that each of its six subplots—the “Pacific Journal” slave melodrama of the nineteenth century, the epistolary section from the early twentieth, the paranoid-conspiracy seventies thriller, the present-day totalitarian old-age Kafkaesque yarn, the clone-war adventure of the near future, and the postapocalyptic jungle saga of the distant one—had its own integrity, its own style, its own present tense. From the start of the movie, we get a hash of crisscrossing plots tied together with music (in a desperate attempt at fluidity) and featuring the same actors with laughably egregious makeup jobs. Our dawning awareness in the book of all the echoes and crosscurrents becomes fast-food metaphysics on a cartoony canvas.

The cinematography is indifferent, and the editing too on the nose, but it’s the acting that’s the shocker. The cast comes off like a third-rate stock company on the matinee after the night on which everyone got bombed on mescal (and possibly mescaline). And do you think viewers who haven’t read the book will know what’s going on (assuming they can understand the dialogue, much of which the soundtrack garbles)? It’s all flash cards until the last movement, when such lines as “My life exists far beyond the limitations of me” are like Buddhist placards.

Kathryn Schulz: I’m largely in agreement, although there are some things I liked. Ben Whishaw was terrific as Frobisher; he seemed like he’d stepped out of my mind onto the screen. The seventies section is probably as close as the movie comes to mimicking Mitchell’s feel for genre.

But there are many more things I disliked. To pick up on your question about the garbled dialogue, the linguistic gobbledygook drove me absolutely batty. One of the many things I loved about the book is the way it shows language changing over time. You get immersed in these successive argots, from a mid-nineteenth-century English that feels archaic to an invented 22nd-century idiom that is dystopically new to an even more distant future where the language has lapsed back into something primitive again. It’s slightly difficult to manage that newest language even in the book, but by the time you get there, 300 pages in, Mitchell has earned your trust. The movie, by contrast, opens with Tom Hanks babbling in this made-up lingo.

D.E.: You can tell watching Cloud Atlas why the Wachowskis responded to the material—not only for its notion of a cosmic commingling but its racial themes. The siblings have a yen for miscegenation, both literally and spiritually. The strain of gnosticism in The Matrix has here become a full-fledged transmigration of souls, the body but a weak and temporary vessel. And for the Wachowskis, the Powers That Be are those who preserve artificial boundaries—racial, sexual, economic, and spiritual. Free will in their films is a matter of learning to “free your mind,” as Morpheus tells Neo. And once you’ve freed your mind, there is but one possibility: revolution. Social and economic justice for all!

I’ll concede that the thirties section is smooth, the music lovely, and the performances of Jim Broadbent and Whishaw better than good. The seventies action plot—car crashes, shoot-outs—is standard stuff but hits its marks. Put it all together, though, and you’ve still got multiple B-movies bicycle-pumped into something supposedly momentous.

K.S.: Many have objected to the use of “yellowface” in the film—makeup-ing the heck out of white actors so they can play Korean roles. You’d have to be oblivious to the history of racism in the United States to blow past that objection, but if you were going to mount a defense of it here, you’d point to its literal and figurative contexts. The literal context is that every major actor in this film plays multiple roles, and many of them change gender and race along the way. The figurative context is the one you cite: the thematic emphasis on the transmigration of souls, which I think means we’re supposed to take the “yellowface” and “whiteface” and “womanface” and whatever-face as a sign that oh, hey, we’re all just the same human soul underneath. Radical!

Trouble is, neither of those held up for me in the execution. Yes, each actor reappears in many parts, but I wasn’t able to track the development of a given “soul” over time. So I’m not sure what the cross-casting of all these actors buys us, except maybe an Oscar for makeup. We’re all the same underneath is a lovely sentiment, and to some extent a true one—hey, I’m a humanist, too—but it’s also a cop-out. It lets you drift around in this misty terrain of transmigrating souls, assigning all the blame for evil and all the hope for redemption to individuals without troubling yourself too much over all the structural issues at work.

But I liked watching Cloud Atlas. I never got bored; I was mostly absorbed, and I was interested in watching the way the filmmakers set up and solved a set of problems, even when they did so imperfectly. When Mitchell himself reflected, in the New York Times, on the process of watching his book get made into a movie, he said, “Perhaps where text slides toward ambiguity, film inclines to specificity.” I think that’s right, and it’s one reason I didn’t wholly like the movie; it told me what to think too much. In that spirit, I’m inclined to slide toward ambiguity and tell people they should go see the movie, with one massive caveat. Go read the book first.

D.E.: Your summary is deft, Kathryn, but I can’t let Mitchell’s remark go unchallenged. In fact, I call bullshit. Film is a medium of surfaces, and yet all manner of artists have found ways to gesture toward that which cannot be pinned and wriggling on the wall. The problem is that, for all their mysticism, the Wachowskis are very literal-minded—perhaps even materialists. I admire their daring—and, hell, I didn’t hate watching the movie, although I had a lot of bad laughs at its expense. Only the language grated. When Hanks’s little girl said, “Mama, I hungry,” I wanted to find that missing verb and beat the screenwriters over the head with it. Also, Whishaw’s “What happened between Vyvyan and I …” shouldn’t happen to you, me, or anyone in a $100 million-plus movie.

Cloud Atlas

Directed by Andy Wachowski, Lana Wachowsky, and Tom Tykwer.

Warner Bros. R.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.