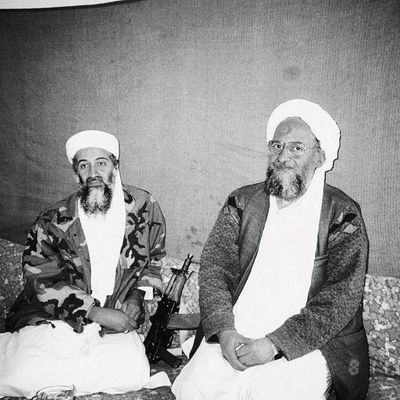

In June, six weeks after Osama bin Laden’s death in Abbottabad, Al Qaeda finally officially confirmed what had been all but a foregone conclusion: that Ayman al-Zawahiri, the prickly Egyptian surgeon who had been bin Laden’s longtime deputy, is the new head of the terrorist group.

The long-held conventional view is that Zawahiri has really been the brains of the operation all along, a jihadist Karl Rove to bin Laden’s George W. Bush. That was once true. But over time, bin Laden eased Zawahiri into the role of one of his followers, albeit an important one.

Like many a revolutionary, Zawahiri is from the upper-middle class, the scion of a family of Egyptian ambassadors, lawyers, and clerics. He joined a jihadist cell in Cairo when he was only 15.

When bin Laden first met Zawahiri in 1986 in Peshawar, Pakistan, Zawahiri was already a veteran militant, having served three years in Egypt’s notorious prisons for his revolutionary activities. Zawahiri was by then convinced that the Arab world had turned away from true Islam, and was calling for the violent removal of the “near enemy,” Middle Eastern regimes run by their supposedly “apostate” rulers. For Zawahiri, bin Laden also was an intriguing figure: someone whose battlefield exploits in the jihad against the Soviets were well known in the Arab world—and with deep pockets, too. At the time, bin Laden was interested only in fighting non-Muslim forces that had invaded Islamic lands, as the Soviets had done in Afghanistan. Zawahiri gradually won over bin Laden to his more expansionist view of jihad.

But it was bin Laden who later urged Zawahiri to see that the crux of the problem was not the Middle Eastern “near enemy” regimes but the “far enemy,” the United States, without the support of which the autocracies in countries like Egypt and Saudi Arabia would simply crumble. Portraying the United States as Al Qaeda’s main enemy also had the useful side effect for bin Laden of uniting a number of militant organizations with purely local agendas, such as Zawahiri’s Egyptian group, under his own banner as the leader of worldwide jihad.

When bin Laden and Zawahiri met again in Taliban-run Afghanistan in 1997, the relations between them were starkly different. Bin Laden was on his way to becoming a global celebrity as the undisputed leader of the global jihadist movement, while Zawahiri headed a small and impoverished cell of Egyptian terrorists. Bin Laden even kept Zawahiri in the dark about his plans for 9/11 for years, telling him only in the summer of 2001.

By then, bin Laden ran Al Qaeda like a dictatorship. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the operational commander of the 9/11 attacks, explained: “If the Shura council at Al Qaeda, the highest authority in the organization, had a majority of 98 percent on a resolution and it is opposed by bin Laden, he has the right to cancel the resolution.” Bin Laden’s son Omar said that members of Al Qaeda even had to ask his father’s permission before they spoke, saying, “Dear Prince: May I speak?”

If bin Laden was the prince of jihad, Zawahiri was its micromanager. One memo from Zawahiri to militants based in Yemen asked them why they had bought a new fax machine for more than $400 and griped about their lack of accounting of money spent. Perhaps his central contribution to Al Qaeda’s strategy was his advocacy of efforts to acquire chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction.

It’s a truism that Zawahiri lacks bin Laden’s charisma. But even if he had it, he would still likely be unable to turn Al Qaeda around given the cards he’s inherited. In recent years, support for Al Qaeda and its signature tactic of suicide bombing has cratered around the Muslim world, while many of the group’s leaders in Pakistan have died in drone strikes. But Zawahiri points out in his autobiography that it took two centuries to eject the Crusaders from the Middle East during the Middle Ages. Zawahiri is utterly convinced that Al Qaeda’s God-ordained victory against the United States will happen, in time.

Peter Bergen, CNN’s national-security analyst, produced the first televised interview with Osama bin Laden, in 1997. His most recent book is The Longest War: The Enduring Conflict Between America and Al-Qaeda.