| News | |||||||||||||||||||||

| How the War Came Home | |||||||||||||||||||||

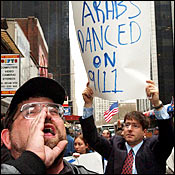

| The searing images of the conflict in Israel and the surge in anti-Semitism in Europe are breeding a tough-minded new mood among American Jews. Peace is not the most important idea now. Survival is. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| BY AMY WILENTZ | |||||||||||||||||||||

They're watching tanks, suicide bombs and their bloody aftermath, the paralysis of the spiritual capital: Jerusalem. Of course, every single tiny moment in Jewish history holds some fascination for one Jewish person or another. Every choice made by every Jewish leader, renowned or forgotten, seems decisive, and any moment is almost sure to be a moment of crisis for this people who seem to live from catastrophe to catastrophe; certainly that's how we feel as history carries us onward; that's what we're taught from the earliest days. This is the catastrophe now, we say; here comes the Holocaust again, we say. We whisper: Do they hate us? "As I've said before, if a loudspeaker goes off and a voice says, 'All Jews gather in Times Square,' it could never surprise me," says Nat Hentoff of The Village Voice. What I've heard in the past month or so -- at synagogues, at middle-of-the-road American Jewish organizations, and at Manhattan dinner tables -- is that kind of fear, more than anger. Especially from people who were pretty devoted to peace; they are feeling betrayed by the Palestinians and terrified that Sharon's response is wrong but the only possible response. Their feelings toward the Arabs are hardening, and when they look at Sharon, they catch themselves thinking that maybe he didn't respond hard enough soon enough -- a scary idea, when you look at what's become of, say, the Jenin refugee camp. Also, everyone I've heard from and talked to, from the littlest lady in the back row to the most important liberal Jewish thinkers, they all seem to think the media is against them. When reporters cover Israel as its Army does something violent, the conclusion is quickly drawn that the coverage is biased against Israel. ("They didn't mention the suicide bombers when they were showing what happened in Jenin" -- I heard this over and over.) They particularly resent the photos the Times has dedicated to the flattened camp and to Palestinian victims pulled from the wreckage. It's as if they want everyone's eyes turned away, including their own.

Their faces are so earnest, so troubled -- they remind me of the faces you saw just before the Twin Towers pancaked to the ground, those shocked office workers from downtown, shielding their eyes and watching something unimaginable about to happen. But these are just American Jews sitting in auditoriums or in synagogues or in each other's dining rooms -- sitting in comfortable places talking, as they do endlessly these days, about the Situation.

We were a peace-loving people once, or so some of us believed. I remember it; we all remember it because it wasn't long ago. We were comfortable enough in America and felt secure enough in Israel (though never very secure), secure enough to want to make those conditions permanent. Through peace. It seemed the only way. We'd done war, after all. Terror continued, and the endless occupation went on being hated by the Palestinians, and the settlements kept on growing, but these seemed to many like facts of life, slowly being transformed by time and human effort into something different, something that might even end -- on both sides of the Green Line one day. But this year, what Israelis call "the facts on the ground" changed in quality and in quantity -- that's putting it nicely, without mentioning the dead and their particulars -- and American Jews, too, began to get tough. The previously almost benign temperament of the liberal community began to change. By now, it is very different from what it was a year ago. "The Passover suicide bombing was the breaking point for the middle ground of American Jewry," says Samuel G. Freedman, author of Jew vs. Jew. "Virtually every American Jew goes to a Seder dinner, so the attack felt very intimate for American Jews. The other thing that that bombing did was act like a trigger that then linked up a bunch of other events: the Durban conference, the attacks on synagogues in France, Nobel wanting to take away Peres's prize but not Arafat's, the Danny Pearl killing. . . . All those dots got connected. . . . You have to defend yourselves." No one has forgotten that Pearl's captors made him confess repeatedly that he was a Jew before beheading him. People are feeling threatened to their very roots, not just in Israel, where the suicide bombs are, but in Europe, where there's actual writing on the walls of a particularly virulent sort. And as usual, a sense of vulnerability does not bring out kindly or philosophical traits. American Jews are ready to go in with the tanks, and that's one of the factors that has allowed the Israelis to go in with the tanks. There's a callousness now, too, a kill-or-be-killed mentality, almost a desperation, that's new, or at least that hasn't been expressed since the Yom Kippur War. I have a friend who is an American Israeli with a son in the Israeli Army right now. When I ask him how his son is, he says: "Armed, dangerous, and killing as many Palestinians as possible, I hope." My friend, too, once thought Oslo might work. But he wasn't big on it. He says to me: No one cares anymore about the death of a Palestinian baby, or the pain and distress of any Palestinian. "Those days are over, kid," he says. Tainting the environment in which all this is happening are the creeping inroads anti-Semitism has made in Europe. Or you may prefer the formulation of Zev Chafets -- former director of the government press office for Menachem Begin who quit over the Sabra and Shatila massacres and who is a current Daily News columnist -- who quaintly calls it "the spasm of anti-Semitism that is engulfing Europe." There's no question that the Arab press's treatment of September 11 (no Jews in the Twin Towers!), plus recent incidents in France, Amsterdam, and Italy, and the April synagogue truck bombing in Tunisia (not to mention the grand electoral success of the great hater Jean-Marie Le Pen in France last week) have made people nervous that the wave of events in the Middle East is rekindling some unstoppable worldwide surge. Faced with these facts, there's been an unmistakable drawing together. There was the April 15 rally in Washington. And last week, rabbis from West Side synagogues of all denominations and members of their congregations met under the auspices of the Jewish Community Center in New York, to hold an hour of poetry, psalms, and readings at the Jewish Center, an Orthodox shul, as a demonstration of united commitment to peace in Israel and to the survival of the nation. "That's never happened before in the history of the community," Debby Hirshman, the JCC's executive director, says. "The challenge for us as American Jews is to keep finding the ways to bridge communities" -- by this she does not mean a bridge between Israelis and Palestinians but between various kinds of American Jews. It's a funny way of thinking about the "challenge" right now, but meaningful, because that, in part, is really what's happening. American Jews are coming together because they are worried about what might happen if they don't. "I'm worried about whether Jews are as confident of Israel's survival as the Arabs are," says Jonathan Jacoby, a consultant and a founding director of the Israel Policy Forum and the New Israel Fund. "Has this horrible situation sent a lot of us back into a feeling of perpetual victimization? I have that inclination also. A part of every Jew wonders whether we can ever trust any situation. A part of the American Jewish experience is one of post-survival, in which we're not trying to survive but instead we're existing and thriving. I feel as if some people are losing that sense." A truism that is true is that jews only agree with each other, only "come together," under duress. Now they are under duress. And this is what the conversation most often sounds like now: Arafat walked out of Camp David. He turned down Israel's best, most generous offer, virtually everything he'd ever asked for; then he started the suicide bombings; in their hearts, all the Palestinians want to drive the Israelis into the sea; the Europeans are anti-Semites; the Arabs are anti-Semites; the media is biased against the Jews; peace is over; war is ugly; this war is necessary. No longer a topic admissible for debate: Sharon's descent on the Temple Mount. Still up for grabs: the occupation, the settlements. "Well, what are we supposed to do?" might be the question that best characterizes liberal Jewish reaction to Sharon's West Bank push. "What exactly do you do when 23 of those suicide bombers came out of Jenin?" asks Emanuel Azenberg, a Broadway producer.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

From the May 6, 2002 issue of New York Magazine.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||