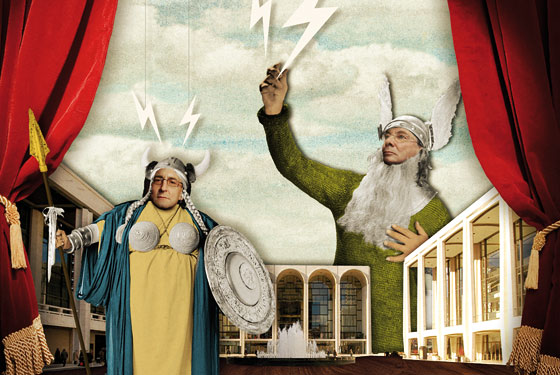

The flame-fanning artistic director Gérard Mortier doesn’t officially take over New York City Opera until 2009, but Lincoln Center is already starting to look like the battleground for some fascinating—and potentially ugly—opera wars. The Met’s general manager, Peter Gelb, has been laboring to transform the company’s dowdy prestige into a reputation for boldness, invention, and dramatically compelling productions. (Oh, yes, and good music too.) Now along comes Mortier, who has sown both outrage and excitement at the Salzburg Festival and at the Paris Opera, declaring his intention to reinvent opera. In Europe, this meant dark, bewildering productions, such as last spring’s Paris staging of Janácek’s The Makropulos Case, which reportedly was set in a public bathroom, complete with urinals and stall. (This was before the Wide-Stance Affair.)

Mortier and Gelb have said that since the two companies have different missions, they will negotiate, not compete, which is a little like saying that since the Mets and the Yankees play in different leagues, there’s no animosity between them. The two managers couldn’t even agree on how to characterize the agreement. Mortier called it a kind of Versailles treaty (an odd metaphor, since the first one led to World War II); Gelb clarified that the two men had come only to very general understandings, and had certainly not divvied up the repertoire as if it were conquered territory. Gelb has pointed to the Met’s live broadcasts to movie theaters as a way of spreading the art form; Mortier has called them “exactly the wrong direction.” It would be preferable, he said, to bring people out of the movies and into the opera house. Gelb has made wooing the public a central goal, whereas Mortier appears inclined to pummel it into enlightenment: “The creative artist is a rebel … a prophet. He tells the public things that the public does not want to hear.”

Gelb has been getting good reviews as a manager, raising ticket sales, pioneering a multipronged media strategy, and promoting his star singers. Mortier, whose fall season in Paris was ruined by a technicians’ strike, has to quell a lot of doubts here, but then so did Gelb. Mortier’s detractors predict that he will bleed the company dry, spook patrons, hire mediocrities, mount tasteless productions, and be gone in a couple of years. His defenders call him a visionary. Either way, two fertile egos facing off across the plaza could prove worthy of dramatic treatment—in an opera, say.