Lenny Izzo stands before the 50 or so people gathered in his office on a chilly Saturday and utters a single, thrilling word: “Wealth.”

“The fact is, most of us have not been conditioned, have not been mentored, have not been coached, have not been inspired, have not been motivated to go out and generate wealth,” he says with the rat-a-tat-tat delivery of a televangelist. “Yes or no?” he asks, scanning the crowd intently. “We’ve been motivated, inspired, encouraged, taught—to do what? To work hard. To get a steady job. And where has that gotten us?”

“Nowhere,” grunts a ruddy man holding a Dunkin’ Donuts cup. The crowd murmurs its assent, as Izzo knew they would.

Izzo knows how the people in the room feel because he used to be one of them. Two and a half years ago, he’d looked up from his desk at the Huntington, Long Island, wellness clinic he’d run for 30 years and realized he was stuck. All of the responsibilities, all of the stuff he’d accumulated—the mortgage payments and car payments and insurance payments and credit-card payments and student-loan payments for his son and daughter—weighed on him, as if he were a hoarder whose collection was collapsing on top of him. “I realized I didn’t have an exit strategy,” Izzo says a few days later, sitting among the collection of self-help books, swords, and dream catchers in his office. Tall and pale, he has intense blue eyes and a head that, once you get to talking to him for a while, seems not quite bald but more like the hair has made way for all the ideas churning inside.

Then Izzo was saved. Not by Jesus, but by a cold call from a woman who told him he could get rich selling vitamins. Well, she didn’t say that, exactly. She presented him with an opportunity to change his life by distributing vitamins through a business model, pioneered by Amway, called “network marketing.” Izzo was skeptical. But for some reason he stayed on the phone.

It worked like this, the woman said: He would order the vitamins from a company called Ideal Health. She would earn a commission on the sale and he, in turn, would become a part of her team and encourage other people to buy the vitamins. For those sales, Izzo would earn a commission, as would she (his “upline”), and then the people he sold the vitamins to would become part of his sales team and would go on to create their own sales teams, who would go on to create their own sales teams, etc., ad infinitum, all of them funneling commissions from their sales up to Izzo and the woman on the phone. As he listened, “something clicked,” Izzo says. “I saw the beauty of the business model. And I said, ‘How can I do this, and do this big?’ ”

In two weeks, Izzo had signed 30 people onto his “downline.” His swift work caught the eye of Ideal Health’s president, Lou DeCaprio, who called him at the office. Izzo doesn’t remember what DeCaprio said to him that day, but “he touched my heart,” Izzo says now, tearing up at the memory. “When we got off the phone, I set some pretty amazing goals for myself. I realized I had to stop being a healer and start being a leader and a teacher.”

Izzo has not yet achieved all his goals—network marketing hasn’t enabled him to quit his day job. But it has changed his life. And every week, he holds seminars encouraging other people to change their lives, too. “This is a time,” he tells the crowd, “where extraordinary things are going to happen for ordinary people. This opportunity that has called us is so much bigger than we can imagine. And what it’s about is about making ordinary people experience extraordinary wealth.”

They just have to believe. “A big part of this is believing this is real. You have to believe in yourself, believe in the products, and believe in Donald Trump.”

“The name is hot!” Donald Trump booms over the speakerphone from his office at 725 Fifth Avenue, where, ever since The Apprentice breathed new life into his brand, he has presided over an ever-diversifying array of businesses. He is, of course, speaking of his own name. “It’s on fire!”

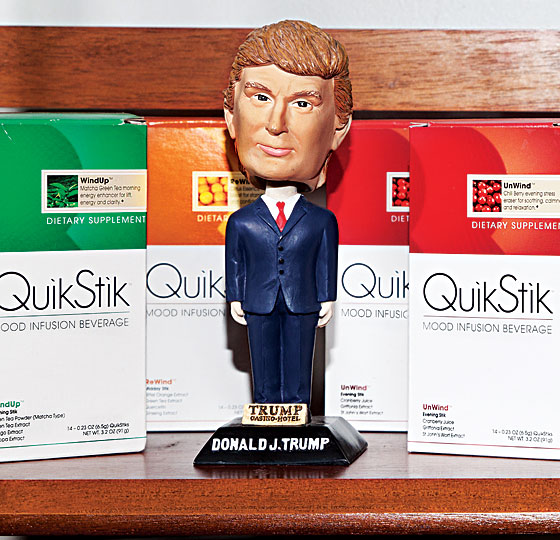

In March 2009, Trump purchased Ideal Health, rebranding it the Trump Network. Though the packaging has now been imprinted with the Trump family crest, the product line is still much the same. There are the two multivitamins: Prime Essentials and the more expensive Custom Essentials, the ingredients of which are determined by the Trump Network–branded PrivaTest, a urine test that claims to determine which vitamins the user needs. There’s also a line of healthy snacks for kids called Snazzle Snaxxs, QuikStik energy drinks, and a Silhouette Solutions diet program. With the Trump investment, the company has added a skin-care line that goes by the seductively foreign name BioCé Cosmeceuticals.

Next year, the Trump Network plans to add more products and extend its reach to Europe and Asia. The goal, Trump says, is to eventually become bigger than Amway, now an $8.4 billion company and the giant in the field. Whether or not the people of Laos will spring for a skin-care line from a man famous for his perma-tan, some Long Islanders seem convinced.

“People have said, ‘This is Donald Trump’s network-marketing company? I want in,’ ” says Alex, Izzo’s pretty 29-year-old daughter, who quit her job and moved back in with her parents last year in order to become a marketer, as the people in the network call themselves. “I was talking to a woman the other day and she said, ‘If I can’t trust Donald Trump, who can I trust?’ And I said, ‘You’re totally right.’ ”

Back at the seminar, her father asked to see a show of hands. “If there’s any doubt in this room, I’d like for you to show yourself,” he said. None was raised. “Rest assured, you cannot fail at this,” he said. “You can only give up.”

The people in Izzo’s office have plenty of reasons to be doubtful. Even though brands like Avon, Mary Kay, and Tupperware have become household names, network marketing has a somewhat unsavory reputation. Fraud is so rampant that the Federal Trade Commission has a section on its website warning people about them: “These plans, often called ‘multilevel marketing plans,’ sometimes promise commissions or rewards that never materialize,” it reads. “What’s worse, consumers are often urged to spend or ‘invest’ money in order to make it.”

In suburbs like the ones found on Long Island, where network-marketing fads tend to come and go with the frequency of LIRR trains, people raise an eyebrow at any new scheme that purports to make them rich.

Dylan Florea, a 31-year-old commercial real-estate broker at Izzo’s seminar, ticks off a list of programs he’s been introduced to. “Kangen Water, this water-purification system I bought this filter for. MonaVie, which is a drink made with … what are those berries? Acai? Melaleuca, this all-green cleaning line. Herbalife, which I thought was totally subpar.”

“I mean, it’s Long Island,” says Richard Chester, the cheerful, white-mustachioed accountant who brought me to the meeting. “There’s always something people are trying to rope you into.”

But this time, he thinks it might be different. “Who in their right mind would not go with something Donald Trump is promoting?” he asks.

“When you think of Donald Trump as a brand, what do you think of?” asks DeCaprio. The stout, tan president of Ideal Health looks at me expectantly, his suit as dark and crisp as his hair. Since bird-of-paradise hairstyle, Muppet eyebrows, fights with Rosie O’Donnell, “Best sex I ever had,” don’t seem to be the words he is waiting to hear, I stay quiet. “Prestige products, best in class, really being successful,” he says. “No matter what happens, he can come back out of the ground like a phoenix and get right back on top again. He represents entrepreneurialism for this country. He represents success.”

However improbably, Donald Trump, who will be roasted on Comedy Central this spring, has over the past few years come to represent those things to many people. Though recently he’s suffered a few setbacks: Two Trump-branded condo projects in Florida and Mexico failed last year; a number of buyers at Trump SoHo sued, claiming they’d been misled about the sales rates at the property; and ratings for The Apprentice are down 45 percent. Trump, with characteristic bravado, brushes off reports that he is losing his luster. “The brand has never been stronger!” he says. “We’re setting records in virtually every category! We just sold one of the most expensive apartments in New York. We’ve got the No. 1-selling tie at Macy’s, and we’re selling the hell out of shirts. And we’re expecting the Trump Network will do very well.”

Network marketing is an unusual foray for Trump, because it’s not seen as a luxury field; it tends to attract people who are undereducated, underemployed, or just underappreciated—people who “feel kind of invisible,” says Nicole Woolsey Biggart, author of Charismatic Capitalism. But network marketing can be a cash cow for those who own the companies, which tend to do well in bad economic times, when people are broke, desperate, and angry at the system. Even in good times, there’s not a lot of downside to owning one: The IRS doesn’t recognize marketers as employees, so you don’t have to pay them a salary or benefits. And owners can collect on even the worst sellers, who are usually required to purchase a minimum amount of products per month. Warren Buffett has called one of his network-marketing companies “the best investment I ever made.”

Trump was likely thinking of Buffett when he began casting around for a similar company to buy in 2008. He came to Ideal Health through his longtime lawyer Jerry Schrager, who caught DeCaprio doing a business presentation in New York. DeCaprio is a veteran of the network-marketing scene, along with his partners, brothers Todd and Scott Stanwood. They’d all worked for Nu Skin, another vitamin and skin-care purveyor, during the time it expanded from small domestic operation into a $2 billion global company, and became motivated to strike out on their own. Ideal Health, which they’ve run for fourteen years, thrived in large part because of the rapport DeCaprio has with prospective marketers.

“Lou can see my success years from now and paint a picture for me, which is amazing,” Alex says. “He’ll say, ‘You’re going to be my youngest, most successful person in the company.’ He can just see it.”

DeCaprio’s visions aren’t always accurate, according to one former Ideal Health marketer, who says she paid $12,000 to film an infomercial with a company Ideal Health had partnered with because DeCaprio promised it would “take her business to the next level.”

The infomercial never aired, says the woman, a single mother from Michigan, and thus began a process of disillusionment. “In the beginning, I thought it sounded like a pyramid scheme,” she says. “But then I would go to the meetings and just be taken up by the excitement.” After the infomercial incident, she began to wish she had trusted her initial instincts. One of the products she says she distributed for Ideal Health, Supreme Greens, was involved in a lawsuit by the FTC for false claims that it cured cancer. And a Freedom of Information Act request from a lawyer she hired revealed there were dozens of FTC complaints against Ideal Health from people, some of whom claimed they’d been told they’d make money and lost thousands of dollars.

DeCaprio says these losses are often indicative of a failure on the part of the marketers, not the company. “Many times, if people aren’t having success in recruiting,” he says, “it has to do with not believing in themselves.”

The former marketer thinks this is simply manipulation. “If you fail, you think it’s your fault, like, ‘Oh, I didn’t believe in myself enough.’ I can’t believe Donald Trump put his name on that company.”

The people at the Trump Network are trained to defend against allegations that it’s a pyramid scheme. Toward the end of Izzo’s seminar, we break into pairs to practice what to say when potential invitees suggest the business is a pyramid scheme. My partner is Billy, a former Wall Street trader who has worked his way up to “diamond director,” one of the highest levels in the company. The levels are determined by the number of people you recruit and the amount of products you and your downline purchase. “What’s a pyramid scheme?” he asks me. “Like the food pyramid? Like the Catholic Church? What about where you work? If you ask me, corporate America is a pyramid scheme. All the people on the top make all the money. The people at the bottom are spinning their wheels.”

Then he plays his Trump card: “You think Donald Trump would involve himself in a pyramid scheme?”

The line between network-marketing companies and pyramid schemes is thin but definite. If you only make money by recruiting other marketers, it’s a pyramid scheme. Trump Network marketers get a $100 to $225 bonus for each person they sign up, and a bonus of $10 to $125 for each person they sign up (depending on the level). They also make between 4 to 7 percent commissions from products sold in their downline. For an aggressive salesperson, it can add up. Billy has recruited twelve people, including his sister, who have recruited an average of eight people. He’s made enough money from the program to keep him from having to sell his house, he says, and it’s all based how big he’s grown his network. But he insists it’s not a pyramid scheme. “There’s a product,” he reminds me.

Trump, too, is adamant about that distinction. “With this company, I let it be known right from the beginning,” he tells me. “Product first. Marketing second.”

In the past, network-marketing companies have been targeted by the FTC for making claims about how much income a person can make, which is probably why the Donald is careful to point out the program won’t necessarily make you rich. “This is supposed to be a second income for people,” he says. “This is not about them quitting their job.” Though “for some of them, it might lead to that.”

Many of the people at Izzo’s hope they’ll be the ones. Back at the meeting, Izzo asks people to share their feelings about the Leadership Weekend they attended the previous Saturday, which featured a speech by DeCaprio. One woman begins speaking but gets too emotional to go on. Doug from Bohemia takes over. “After the speech, I walked over to Lou, because I wanted to tell him that I was making a five-year commitment to the business,” he says. “And he grabbed my arm, and he said, ‘In two years, you’re gonna be wealthy if you work this thing.’ And I’m like, ‘Holy crap!’ He was dead serious. I was like, ‘I’m in.’ ”

The founders of Ideal Health believe in dreaming big. Maybe because their dreams came true. “Lou told us that he put a picture of Donald Trump and his name on a dream board,” Dylan Florea tells me. “Because he wanted to partner with the Donald’s energy and, of course, his financial track record. And it happened. That is a true story.”

After the deal with Trump was completed, DeCaprio and his partners moved out of their tiny office and into a new 70,000-square-foot headquarters decorated in high Trump style: muscular beige walls, glass doors embossed with the Trump family crest, crystal chandeliers, and lounge music piped into the lobby. Trump hasn’t been there yet, but he’s there in spirit. In the warehouse, a flag bearing his scowling visage stands sentry over the rows of storage shelves.

Richard Chester’s office in Rokonkoma is easy to spot because of the painting of Mickey Mouse on the wall outside. His wood-paneled room is the third and last in the railroad-style building; the first is occupied by the three cheery women who run the Welcome Travel Agency, and the second is inhabited by five extremely large cats, who spend their days wandering around a cat wonderland, built by Chester, that includes a section of carpeted walls for climbing and a suspension bridge leading to an outdoor play area. One of his reasons for signing up with the Trump Network is that he wants to one day be wealthy enough to start a cat orphanage, like one in Florida where a guy has 30 acres for cats to roam.

But right now, it’s tax season, and he’s got his hands full. He offers me an orange QuikStik and settles down behind his desk, on which sit three sets of business cards, one for his accounting business, one for his mortgage business, and one for the Trump Network. “You always have to diversify!” he says.

Chester was skeptical when a neighbor approached him about joining the Network, but the video of Donald Trump telling a version of his life story on the company’s website won him over. “I felt like he was speaking to me,” he said. “This is a man who was down in the dumps and came back! Now everything he touches turns to gold!”

So he joined as a FastStart Gold, “the best level to start at.” He spent $1,200, which got him two kits containing samples of the products. But, actually, now that he thinks about it, it cost a little more than that. The business cards were extra ($85, though there is a $50 one if you want to be cheap about it). And so was his Trump Network web address (the first three months were free, but it now costs $19.95 a month). Then he ordered the Custom Essentials vitamins ($59.95 a month) because he felt his belief in the Trump Network wouldn’t seem genuine if he didn’t take them. For the same reason, he bought a set of BioCé products, even though “I’ve never used a skin-care product in my life,” but now he’s been using them twice a day, and “I do feel like my skin is nicer.”

So far, Chester hasn’t gotten much of a return on his investment. He signed up one person, this guy Ed, for whom he got $110, and Ed signed up one person, so Chester got another $10. And he’s received a few commission checks here and there: for $62, $50, $15. Not exactly Trump money. But Chester admits he hasn’t really been working it, not like Billy or Alex Izzo, who recently purchased a shiny white Acura. For Chester, it’s not about buying a new car. “You know what?” he says. “I go to those meetings, and I just see people learning their self-worth. Learning to never give up on yourself, you can do it, don’t be depressed if someone says no, just pick up your bootstraps and keep going. That makes me feel good.” He believes in the company, and he believes in Donald Trump. “I feel like in his heart, he wants to help people who are down and out,” he says. “If I thought he was just in it for the money, I wouldn’t do it.”