Launched: 2011

Age of CEO: 28

Lesson: Sometimes making 100 percent profit is enough.

Michael Preysman, who launched the online-only apparel company Everlane two years ago with a background in finance but no prior fashion experience, once spent, “like, six hours on Google” trying to determine the manufacturer of his preferred leather wallet, which can run as high as $350. He knew it was stitched in Spain and eventually learned that the southern town of Ubrique was the source. Problematically for his investigation, there are about a dozen factories there. So he flew over and befriended a Spanish woman, who introduced him to the president of the factory in question … and this month, Everlane released its first line of wallets. They top out at $115 and are created from the same Italian leather, cut from similar cows, and sewn in the same place as his (former) favorite.

In Preysman’s view, the casually polished wardrobe many city denizens adhere to is radically overpriced, marked up as much as 800 percent at retailers. Instead, Everlane typically doubles the price it costs to produce each minimal-leaning basic and sells the garments directly, ripping aside the veil on every expense along the way. As a brand, it’s predicated on transparency.

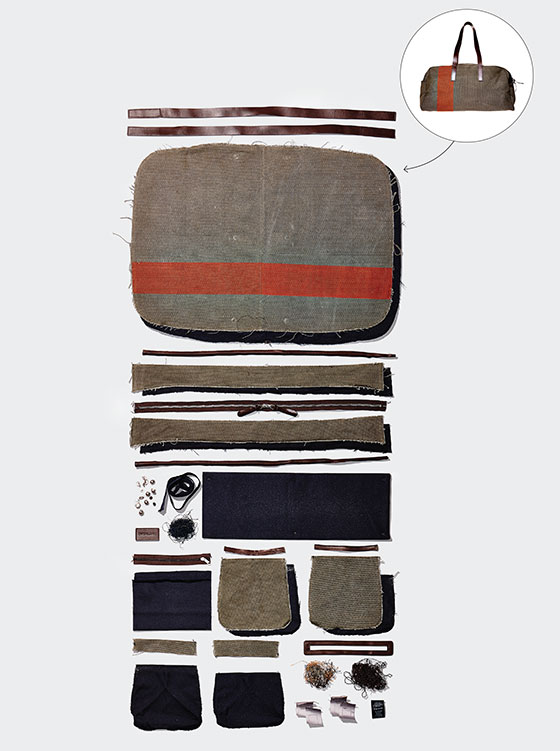

So if you’re in the market for a men’s oxford shirt, you can learn via the Everlane website that they’re sewn in the same factory in Hangzou, China (“one of the country’s most beautiful cities”), as their $80 women’s silk blouse. And for each shirt, it takes $10.77 in cotton, thread, and buttons, $1.22 to cut, $8.35 to sew, $1.97 to “finish,” and $4.61 to transport, for a total “true cost” of $26.92. Everlane sells the button-up for $55 and trumpets that “traditional retail” would charge $110. The same model is applied to such items as Supima-cotton T-shirts, cashmere sweaters, denim backpacks, and canvas duffel bags. For each, Preysman finds something luxurious he thinks he can make cheaper—pants have eluded him, but he’s got his eye on shoes—and uses factories in the U.S., Europe, or Asia (he won’t reveal exactly which, in part because he says it would harm owners’ relationships with luxury brands).

The company’s philosophy dovetails with at least two consumer trends: (1) People want to feel good about where their chickens come from, and their shirts too; (2) nonelitist fashion has become popular among urban elites, as eyeglasses purveyor Warby Parker, shoemaker Tom’s, and others promote the idea of ethical basics for reduced prices. “Someone was bound to apply this model to apparel,” says Anthony Sperduti, a consultant who has helped J.Crew (whence a few of Everlane’s 25 employees hail) and Warby develop cachet. “There is, at the moment, something cool about buying into the idea of rational value.”

Unlike American Apparel, the last company to successfully make $15 T-shirts into a lifestyle, Everlane has a larger goal—to become the thinking person’s solution for not just basics but more extravagant purchases too. This fall, the brand will begin offering such higher-end items as suede weekenders ($195) and leather handbags ($325 to $425). “Hopefully, this is a bag you buy once, and then again in ten years,” Preysman says, sounding awfully rational about a purchase often made for the least-rational reason of all: lust.