When Peter Orszag left his post as White House budget director last summer, it made perfect sense, on several levels, that he ended up in an office next to Bob Rubin. Rubin, the Clinton-era Treasury secretary, had the year before resigned his position as senior counselor to Citigroup, a job for which he was paid $115 million, plus options, over nine years. Rubin’s tenure ended shortly after the bank’s near implosion and subsequent $45 billion government bailout. Rubin was temporarily bivouacked at the Council on Foreign Relations on the Upper East Side, which is something like a gentlemen’s club for the Davos crowd, one of the places, much like the West Wing of the White House, where finance and civic engagement meet and mix. Orszag was in preliminary talks with NYU about joining the faculty, but Rubin talked with Orszag about joining the Council on Foreign Relations instead. It was an influential perch from which the 42-year-old economist could write op-eds, give speeches, and travel the conference circuit. But the Council, for someone like Peter Orszag, was not a place to linger. It was a place to pass through on his way to somewhere else—and that somewhere else was Wall Street. For one of the most talented economists of his generation, the revolving door was about to spin.

Shortly after leaving the White House, Orszag talked to Rubin’s close friend Roger Altman, the former deputy Treasury secretary who founded the boutique investment bank Evercore Partners, about joining his firm. But then Orszag met another one of Rubin’s friends, Lew Kaden, a top Citigroup executive, at a private dinner at the Council. Kaden, a former lawyer for Davis Polk and aide to Bobby Kennedy, had himself been brought to Citi by Rubin, even though Kaden had had no banking experience.

Orszag was already deep in talks with Altman, but Kaden kept pressing, which is how Orszag found himself one morning a few weeks later in the Park Avenue office of Citigroup CEO Vikram Pandit. Pandit had a problem—one that a man with a pedigree like Orszag’s was tailor-made to solve, even if he never made the firm a dollar. Citigroup was the most high-profile of Wall Street’s basket cases, the definitionally too-big-to-fail institution. With massive exposure to the housing crash and abysmal risk management, the firm cratered, surviving as a virtual ward of the state after the government injected billions and took a 36 percent ownership position. Along with AIG and Fannie and Freddie, Citi came to be seen as a pariah institution, felled by management dysfunction and heedless greed in pursuit of profits. Complicating matters for Citi, the wounded bank found itself tangled in the populist vortex that swirled in the crash’s wake. On the left, there were calls that Citi should be outright nationalized, stripped down, and sold off for parts. Pandit was called before irate congressional-committee members to answer for Citi’s sins, an ignominious inquisition captured on live television. In January 2009, under pressure, Citi canceled an order for a new $50 million corporate jet.

There was plenty of blame to go around at Citi. Chuck Prince, a lawyer by training who succeeded Citi’s outsize former CEO Sandy Weill, had little grasp of the complex mortgage securities Citi’s traders were gambling on. As late as the summer of 2007, when the housing market was in free fall, Prince infamously told the Financial Times that “as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.”

Bob Rubin himself pushed the bank to take on more risk in order to increase its profitability, a move that Citi’s dismal risk management was ill-equipped to handle. Pandit, whom Rubin had helped to recruit in 2007 just as the economy began to unravel, was tasked with cleaning up the mess when he became CEO in December of that year, and his early tenure had a deer-in-headlights character. Eventually, he realized that the asset class Citi lacked most was human capital, of the blue-chip variety. Orszag’s gilded résumé—Princeton, London School of Economics, Brookings Institution, Clinton White House under Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, head of the Congressional Budget Office, White House budget director—would be a valuable investment in this effort. For Citi, hiring a man like Orszag, like Rubin before him, signaled that Citi would be invested in the intellectual marketplace, no mere profiteering bank but a significant American institution. Orszag’s wisdom about markets is certainly valuable; but even more valuable is his role as an impeccable ambassador for the bank, a kind of rainmaker, but at the stratospheric level. Just about anyone will take the call of a former White House budget director. “He’s a guy who can be effective in a lot of rooms,” one Democratic financier who knows Orszag told me.

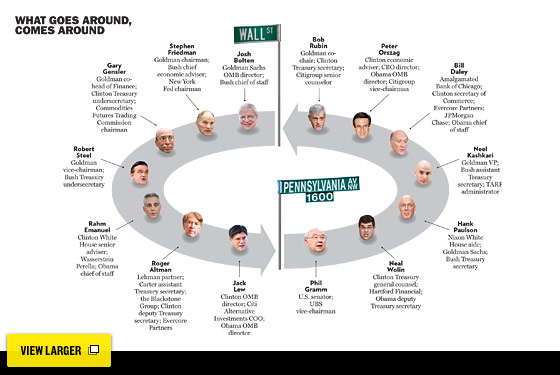

Photographs: Clockwise, From Orszag, Patrick Mcmullan; William Plowman/NBC Newswire/Getty; Jonathan Ernst/Getty; Alex Wong/Getty; Win Mcnamee/Getty; Dennis Brack/Newscom; Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg/Getty; Jb Reed/Bloomberg/Getty; Scott Olson/Getty; Jonathan Fickies/Bloomberg/Getty; Mark Wilson/Getty; Joshua Roberts/Bloomberg/Getty; Mark Wilson/Getty; Scott Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty; Alamy (Street Signs)

Before taking the job, Orszag sought the counsel of Rubin and others among his numerous mentors on Wall Street, in government, and in academe. “I did my due diligence. The view was Citi is not fully recovered, but it’s like this,” Orszag told me over lunch, tilting his hand in an upward trajectory. Certainly, the prospect of making serious money was hard to ignore. Wall Street insiders estimate that Orszag is pulling down $2 million to $3 million a year.

For an ambitious economist like Peter Orszag, going to work for Citigroup represented a choice. As a young staffer working in the Clinton White House, he saw laid before him two different paths: Stiglitzism and Rubinism. There were both intellectual and career-arc components to these. While both are liberal Democrats, Rubin was the consummate insider, whose philosophy was that the free markets, balanced budgets, and limited regulation would create a rising tide that would lift all boats (or at least make Wall Street not complain too much about Clinton’s social programs). Stiglitz, the public intellectual, is as concerned with the boats as with the tide.

Orszag certainly had a lot in common with Stiglitz’s academic mien, having grown up in an intensely intellectual family in Lexington, Massachusetts, outside Boston. His father is a celebrated Yale math professor. But Orszag possessed an ambition that would take him beyond the ivory tower. He ultimately chose Rubinism. It makes perfect sense that Orszag would have been drawn toward Rubin. It must have been incredibly seductive seeing this world, watching the Rubin wing of the Democratic Party move so easily from government to Wall Street boardrooms to the table with Charlie Rose.

When Citi announced that Orszag was joining the bank as a vice-chairman in December 2010, an angry chorus of progressive columnists immediately howled that he was a sellout, cashing in on his Washington connections. Orszag’s critics were animated by their belief that Obama had failed to get tough on Wall Street—and now one of his central economic players was reaping the rewards. Even Orszag’s mentors raised their eyebrows. “I was surprised. I thought he would stay involved in the public sector,” the Princeton economist Alan Blinder, a former professor of Orszag’s, told me. Stiglitz sees the issue as structural, part of the system. “[In the nineties] we tried to get regulation to stop the revolving door, and it’s very, very difficult,” he said. “The appearance is troublesome even if you think these individuals are not affected. Economists find it difficult to believe that incentives don’t matter. What is interesting is these people claim to be economically informed, and yet they believe incentives matter for everyone else, but not themselves.”

When I asked Orszag about the gulf between his two mentors, he told me he doesn’t see a binary choice between the Stiglitz and Rubin worldviews—he still hopes to change the system from within. “I am getting exposed to lots of different issues and problems, and that will then better inform my thinking and public writing,” he told me. “Direct experience need not undermine one’s intellectual integrity; sometimes it can even bolster it.”

The close alliance among Wall Street and the economics departments of the major universities and the West Wing of the White House is the military-industrial complex of our time. That it has an effect on our governance is beyond question. How pernicious and distorting these effects are, how cynical many of its participants might be, and what might be done to change the system are being fiercely debated in Washington.

In fact, to the layperson, the most surprising thing might be the degree to which people like Peter Orszag see the government and Wall Street as, essentially, parts of the same industry. Aside from some bad publicity, going from one to the other is not a leap at all, not any kind of sellout, but a natural progression for a member in good standing of the supermeritocracy like Peter Orszag. In this sense, the last two years have been confusing for these people, because you need public servants who understand capital markets, and who understands markets better than Wall Street? “If you think that someone’s past work on Wall Street disqualifies them from playing a role in something as complex as government, you’ll essentially have people who have no understanding how financial markets operate,” a former senior Goldman Sachs partner who spent time in Washington told me. “That’s a dangerous and scary thing.”

But another way of looking at this is that Wall Street has Washington over a barrel—and the values of one can’t help but be the values of the other. Even in Democratic administrations like the current one, once and future Wall Streeters are in position to pull the teeth out of regulations—for what they see as perfectly sensible, perfectly ordinary reasons. There’s no need to cue the scary music; it’s not a conspiracy. It’s just that having lived in the same worlds, read the same textbooks, imbibed the same maxims, been tutored by the same mentors, attended the same confabs in Aspen and Davos—and, of course, been paid with checks from the same bank accounts—they naturally think the same thoughts. To these people, the way things are done is, more or less, the way they have to be done. To change the system, you have to change the people; but the people are the only ones who know how the system works.

Orszag expresses an easy calm despite the criticism of his recent move to Citi. At the White House, Orszag was known for his supreme self-confidence. “So far so good,” he said breezily, over a grilled-chicken salad, when I asked how he liked his new life as an investment banker. He was adjusting quite well to life in New York. He moved into a big new apartment downtown with his new wife, ABC News correspondent Bianna Golodryga, and was up at dawn with the type-A crowd for morning runs along the West Side Highway. Before our lunch, Orszag had just flown in from London, where he had been meeting with Citi’s managing directors and president and chief operating officer John Havens.

As we spoke, Orszag made clear he understood that by joining Citi, he was stepping into a white-hot center of populist animus. “Look, I faced a fundamental choice,” he said. “I could have been totally comfortable doing something easy, going back to academe or a think tank, giving speeches, having a cushy consulting thing—ironically, which would have played off my White House experience much more than what I chose to do. Or I could have done something new, which would be harder.”

Orszag’s comfort in his new job may have something to do with the relief he feels at being out of the White House. By last summer, Orszag’s relations with Rahm Emanuel and others had soured—badly. Depending on whose spin you believe, Orszag quit over principle, telling friends he was upset by Washington’s refusal to get serious about the deficit. A less favorable view is that Orszag was marginalized by Emanuel and David Axelrod. “He was accused of leaking and being disloyal,” said one Democrat close to the players. “The press loved Peter, which was part of the reason why the White House didn’t love him.”

His falling-out with the White House was a dramatic reversal for Orszag, his first real career stumble. Looking back, Orszag now says he didn’t even want the job. “I didn’t want to do it,” he told me. “Having worked in a White House before, I knew how the infighting can become all-consuming, and I didn’t want to fall into that trap again. Many of my mentors warned me that despite the ‘no drama’ Obama campaign, once in office this White House would inevitably be like others—and possibly worse. And unfortunately that’s exactly what happened.”

Orszag took the OMB job after both Emanuel and Obama personally lobbied him to accept. (When a president asks you to serve, you do it, Orszag told me.) He was initially one of the most visible faces on Team Obama. During his first year in office, he made the rounds on Charlie Rose, Face the Nation, and The Daily Show. As the youngest member of Obama’s Cabinet, Orszag played the part of the rock-star egghead, donning cowboy boots under his navy suits and becoming something of an unlikely hunk, embodying everything that was cool about the technocratic braininess of Obama’s Washington.

All this public attention gave Orszag juice: He transformed the wonky Office of Management and Budget into a power center on the West Wing’s fiercely competitive economics team. He plunged into the intense debates over the $800 billion stimulus and was also a major player in the health-care fight. Orszag was a deficit hawk and clashed with Larry Summers, who wasn’t as focused on the long-term debt crisis. Orszag argued that some of the biggest things the White House could do to tame the deficit were to tackle health care and repeal all of the Bush tax cuts. True to his Rubinesque roots, Orszag lobbied for the deficit commission; Summers was against it, telling aides that the commission posed “McChrystal risk,” because its findings could box Obama into a corner, the way the former general’s leaked report about boosting troop levels in Afghanistan did.

Orszag, who had run his own team at the Congressional Budget Office, didn’t always defer to Summers, and at one meeting, the pair reportedly fought over a chair across from Obama. “Peter was somebody who could be a foil to Larry. He suffered from a small case of Summers-itis, where you display your brilliance,” one budget-policy wonk who has worked with both men explains.

Orszag’s public profile, once one of his biggest assets, became a liability. In January, a “Page Six” headline blared, “White House Budget Director Ditched Pregnant Girlfriend for ABC News Gal.” The tabloid detailed how Orszag had split with his pregnant girlfriend, the Greek shipping heiress Claire Milonas, and taken up with the younger Golodryga. The baby drama was not well received by the no-drama Obama administration. Seven months later, Orszag was out. His departure did not end his problems with the White House.

Not long after leaving the Obama administration, Orszag received an e-mail from David Shipley, then the New York Times’ deputy opinion editor. “We’d really like to get you involved, can I come see you?” he wrote.

Shipley’s offer of a semi-regular economics column intrigued him. For Orszag, writing was something that came naturally. Joseph Stiglitz recalled how he had often assigned Orszag, when he was a 25-year-old member of his staff on the Council of Economic Advisers, to write weekly economics briefings for President Clinton. “Peter is one of the people who can write well,” Stiglitz told me.

A few days later, Orszag and Shipley met, and Orszag agreed to sign on as a columnist. Orszag told Shipley that he wanted to write his debut column about the debate raging in Washington over whether to extend the Bush tax cuts. Congress was preparing to return from recess to vote on the issue. Obama was in full campaign mode, aggressively stumping to let the tax cuts for families earning more than $250,000 per year expire while upholding his signature campaign pledge of preserving the middle-class tax cuts. Orszag argued that Obama should accept a temporary extension of all the Bush tax cuts, then let all of them expire in 2013, including those to the middle class. Orszag’s plan made a certain amount of economic sense from a deficit-hawk perspective—keep the money pumping through the system at the depths of the recession, and then, when things got better, focus like a laser on the deficit. But Obama’s political advisers, as well as Summers, thought it politically daft, seeing as Obama had promised to make the middle-class tax cuts permanent, and also suspected that the Republicans would renege on any such deal about the tax cuts, leaving the Obamans with nothing for their concession. Orszag now says his views on taxes and the deficit were one of the factors that made him decide to leave. “I didn’t think I could be an effective advocate for the administration on making the tax cuts permanent, and I didn’t want to be in office when that happened,” he told me.

The column appeared on September 7, 2010. “The debate was approaching, and I felt like I would regret not speaking out,” Orszag said.

The alliance among Wall Street, Universities, and the White House is the military-industrial complex of our time.

Not surprisingly, the White House was outraged by the op-ed’s timing and content. Orszag’s column provided powerful ammunition to Republicans who were winning with the argument that repealing the Bush tax cuts during the flagging recovery would be bad news. The press seized on the op-ed as evidence that Obama’s brain trust was split on the issue. At a briefing that morning, reporters grilled press secretary Robert Gibbs about Orszag’s column. In private, Rahm Emanuel was upset Orszag hadn’t told him the column was being published. Orszag e-mailed Emanuel to refute the claim he hadn’t alerted anyone in the administration. When I ask Orszag about the op-ed dustup, he told me: “I provided a very senior official in the White House with a very specific heads-up.”

Orszag’s move to Citi not long after the op-ed controversy created more political baggage for the White House, as the administration sought to tamp down populist anger while repairing frayed ties to the business community by hiring former JPMorgan executive Bill Daley and swapping out Paul Volcker with GE CEO Jeff Immelt.

Orszag may have been branded a sellout, but his decision to join Citi wasn’t a matter of simple favor trading. As OMB director, Orszag wasn’t involved in the White House’s banking policy. But as traders and politicians know, perception is often reality. That Orszag was hired so quickly by Citi allowed some to ask who Orszag had been working for all along. But the real dissonance was that most Americans don’t understand the career paths of the meritocracy.

More than anyone else, it was Bob Rubin who made the Democratic revolving door work as smoothly as it has. In earlier years, Wall Streeters were probably not much less powerful in Washington, but the dominant model was that of the tycoon—Averell Harriman, say—who became a statesman. But in Rubin, the roles were somehow fused—he became a financial statesman. The role depended on a surprisingly explicit syllogism, with its own echoes of an earlier American age: What’s good for Wall Street is good for America, and vice versa.

As Treasury secretary, Rubin presided over a remarkable period in the American economy. He arrived in Washington after a storied 26-year career on Wall Street, culminating in the co-chairmanship of Goldman Sachs. Rubin learned early the value of establishing relationships with powerful mentors. Later, he’d attract his own group of devotees, including Orszag, Tim Geithner, and Summers. He’d joined Goldman as a junior trader in 1966, and was taken under the wing of legendary arbitrageur L. Jay Tenenbaum. “Bob was hired as a Young Turk to sit at his desk and do what he was told,” recalls former Goldman partner Roy Smith. “He had a natural intuition for the risk-arbitrage business.”

In 1971, Rubin made partner, and shortly afterward he took over the risk-arbitrage group. Junk-bond-fueled takeovers were sweeping Wall Street. Rubin was at the center of the action, wagering Goldman’s capital on the merger frenzy. Rubin was named co-chairman in 1990, running Goldman alongside Steve Friedman. They were a formidable pair, political opposites (Friedman is an active Republican, and was George W. Bush’s chief economic adviser). Rubin, a longtime Democrat and generous fund-raiser, saw his career in finance as a means to an end. “My real desire … was to get involved in politics,” he wrote in his 2003 memoir, In an Uncertain World. Specifically, Rubin wanted to be Treasury secretary.

In tapping Rubin to run Treasury, Clinton was sanctioning a revolution in the Democratic Party, one that fundamentally redefined the party’s relationship with Wall Street. Rubin, along with Alan Greenspan and Larry Summers, believed in an enlightened capitalism, which would spread prosperity widely. This enchantment with the beneficence of markets became the dominant view in Democratic Washington, hard to argue with when the economy was booming, as it was in the second half of the nineties. Rubin recognized that derivatives posed a risk but effectively blocked efforts to regulate them and pushed for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, the Depression-era legislation that prevented commercial banks from merging with investment and insurance firms (the new law essentially legalized the $70 billion merger in 1998 of Citicorp and Travelers Group that created Citigroup). This faith in the markets was at odds with progressive policy-makers like Stiglitz, Labor secretary Bob Reich, and chair of the Commodities Futures Trading Commission Brooksley Born, who all found themselves shunted aside.

When Rubin left the White House in 1999, he was the most celebrated financier in modern American history. His tenure was crowned by his handling of the Asian financial crisis and the bailout of Long-Term Capital Management. Rubin, along with Greenspan and Summers, was lionized on the cover of Time, which dubbed the troika the “Committee to Save the World.”

At just 60, Rubin was out of government and wanted to return to Wall Street. When Sandy Weill of Citigroup came calling, Rubin seemed to have the upper hand on Wall Street. He didn’t want to get his hands dirty managing or trading or doing deals. He wanted a platform that could afford him wide latitude, leaving time for him to pursue his passion for fly-fishing, write his memoirs, and help shape economic policy. Weill and Citi’s then–co-CEO John Reed agreed, naming Rubin to the newly created office of chairman.

It was a major coup for Weill, who built Citi into a financial supermarket, with trading, commercial banking, consumer banking, investment banking, and insurance all under one roof. Rubin was granted a pay package worth $33 million per year. He had access to Citi’s fleet of private jets and insisted that he have no direct responsibility in running Citi’s sprawling operation. Later, others would see this aloofness and wonder just what, exactly, Rubin was getting paid those many millions to do. “I was hoping he’d be a father figure for Salomon Brothers,” Reed told me. “Jamie Dimon was running it at the time. Sandy didn’t know anything about that, and neither did I. Bob did not play a particularly meaningful role.”

But Rubin soon demonstrated his immense value to Citi. In 2001, Roberto Hernández Ramírez, the CEO of Mexican banking giant Banamex, called Goldman Sachs and said he was looking to make a deal. Goldman pitched the deal to Rubin, and Citi went on to acquire Banamex for $12.5 billion.

And in subsequent years, as Citi found itself facing a barrage of scandals, from the Jack Grubman favor trading to Enron, Rubin couldn’t keep his hands as clean as he’d planned. In 2002, as Enron teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, news leaked that he had placed a call to Peter Fisher, a Treasury undersecretary, and floated the idea that Fisher could advise the ratings agencies to refrain from downgrading Enron’s debt. Citi was a major Enron creditor and stood to lose hundreds of millions in bad loans to Enron if the energy giant failed. It was a particularly ham-handed use of his connections—the network usually operates more subtly than that.

Though he was out of government, Rubin kept a firm hand on the policy-making tiller. From his office next to Weill’s, he worked the phones constantly, just like in his days on Goldman’s risk-arbitrage desk, dialing up Larry Summers, former Clinton national economic adviser Gene Sperling, and other economic-policy wonks. He also recruited several former Clinton aides to Citi, including former Health and Human Services deputy secretary Kevin Thurm and former Clinton budget director Jack Lew. Bob Lipp, a Citi vice-chairman at the time, wondered aloud what kind of expertise the public servants would bring to the firm, asking a senior Citi executive, “What am I going to do with these guys?” (Lipp declined to comment.)

As the Bush White House turned Clinton-era surpluses into deficits, Rubin became increasingly alarmed that the policies he had enacted in the nineties were being abandoned. From his office at Citigroup, he retained powerful tools to shape the Democrats’ thinking on economic matters: money and an influential group of young followers who were moving into key positions in the Democratic policy-making firmament. “One of his many virtues is his ability to spot talent,” Alan Blinder says. One of those young economists was Peter Orszag.

The first time Orszag met Bob Rubin, Orszag told him he was wrong. It was 1995, and Orszag, then 26, was working for Stiglitz in the Clinton White House. Orszag told me he’d seen Rubin make an error during a meeting with Clinton’s economics team. “They let me come to a Cabinet-level meeting, for reasons I didn’t fully understand,” Orszag recalled. “Rubin was secretary of Treasury. He made a small math mistake, and on the way out the door, I wrote a note that said, ‘It was a billion, not a million.’ I handed it to him, and he shoved it into his briefcase. At my desk ten days later, my phone rings, and it was the operator on the line saying, ‘Will you please hold for the secretary of the Treasury?’ He was in Europe, and he called just to say I was right. Which was remarkable.”

Stiglitz had been a powerful early mentor, a progressive voice who was often at odds with Rubin, Alan Greenspan, and Summers. In 1994, Stiglitz took Orszag on a trip to Russia to advise the Russians on transitioning to capitalism. Orszag demonstrated that he was comfortable playing at a high level. He had spent a year in Russia in 1992 working under the economist Jeffrey Sachs and knew many of the Kremlin officials. “He had closer connections to the Kremlin and inside, backdoor connections that were probably stronger through him in many ways than standard diplomatic channels,” Stiglitz recalls.

When Orszag left the Clinton White House, he founded an economics consulting firm with his younger brother, Jonathan, a well-regarded economist. (In 2005, they sold it for a significant sum.) He remained close with Stiglitz, who served on the board of his company. Orszag and Stiglitz co-authored numerous papers. But he was also spending more time with Rubin. In 2006, the two co-founded a think tank run by Orszag called the Hamilton Project, after Alexander Hamilton.

In 2007, Orszag left to run the Congressional Budget Office. Around this time, Citigroup began to founder, threatening to take Rubin’s legacy with it. Citi’s stock plunged, and some of Citi’s traders who watched their net worth evaporate began to blame Rubin for his failure to take a more hands-on role to save the firm. At a private lunch in London attended by a dozen of Citi’s major European hedge-fund clients, Rubin talked openly of his loose affiliation with Citi. According to one person in the room, when a guest asked him what he did at the firm, Rubin half-joked, “Well, they gave me a contract that allows me to travel. I’m here, but I’m not really in an executive position. I don’t run this place.” Afterward, one of the hedge-fund managers went up to a senior Citi executive and said, “I’d never invite Bob Rubin to a client event again. He hurts your image.”

Rubin was angry that he was being blamed for Citi’s crisis. After a barrage of negative press, he refrained from giving interviews. George Stephanopoulos told him in private that “sometimes, these stories set off firestorms, and you can’t do anything about it.”

But whatever touched it off, there was definitely a firestorm of recrimination. One former Citi executive told me Sandy Weill was upset about Rubin’s role. “Sandy is very, very angry,” this executive says. “His legacy is destroyed. He feels Bob should have done more.”

Rubin’s friends say he was unfairly singled out for Citi’s implosion.

“Bob is someone who had an incredible record and left government with that record,” the technology investor and Democratic fund-raiser Alan Patricof says. “You can’t lay the responsibility on him. He was not chief executive officer—CEO means boss.”

Still, Rubin’s time had come. In 2009, he resigned from Citigroup. The tension over Rubin’s tenure at Citi brought together a rare consensus from the right and left. “Citigroup shareholders have suffered losses of more than 70 percent since Mr. Rubin joined the firm. To this day, he appears unable to say what exactly he did for the $115 million,” the Wall Street Journal editorial page wrote in December 2008. “What is clear is that Mr. Rubin encouraged changes that led Citi to the brink of collapse.”

One would have thought that the crash of 2008 would have shattered the Rubin consensus. And certainly, parts of it did shatter. Among members of the Clinton White House, the debates that had been settled a decade ago are now open again, as progressives, sidelined in the nineties, have reasserted themselves—though to what effect is still unclear. During the 2008 campaign, Obama talked boldly of reforming the financial system. But, once in office, he backed off. Austan Goolsbee, an economist who had advised Obama during the campaign, was passed over for a top job as Rubinites, including Orszag, Summers, and Geithner, moved into central posts. The rhetoric changed considerably, much to Wall Street’s chagrin; but the policies were tweaked rather than made new. “Official Washington is starry-eyed when it comes to Wall Street,” Bob Reich says. “They assume if you’re that rich, you must be smart.”

And while the crash dented the confidence of the Wall Street–Washington policy elite, the blow was far from fatal. In November 2008, Rubin attended an economic-policy meeting with Obama and senior aides in Chicago. Reich was there, and he told me that after the meeting, he confronted Rubin about the meltdown. “I asked him why did the crash happen? He said, ‘It was a perfect storm. It was a once-in-a-lifetime event.’ ” Reich, like many progressives, sees 2008 as a reassessment of the Rubin way. “Why was there a complete implosion, if Wall Street is so smart, if markets work so well?”

Orszag understands what’s fueling the populist fervor. “You don’t go through a 45 percent decline in private-sector borrowing without tensions flaring,” he says. At Citi, he’s seeing the system from the inside and developing a more complex view of it, whereas the recent political debate was stripped of all nuance.

“Almost inevitably, the public will think the administration is too close to Wall Street unless it blows up Wall Street, and Wall Street will think the administration is a bunch of flaming liberals if they don’t completely shut down that populist anger,” he says. “Sometimes the small things matter a lot, the odd phrase here, the meeting there that wasn’t handled exactly right. The conversations have been very fraught over the past two years. [Bill] Daley will help on that. It’s also the case that time and moving away from crisis mode will help, too.”

Orszag told me he doesn’t see an inherent conflict between his two mentors. “I find it extraordinarily beneficial to have all kinds of conversations with people who have different worldviews,” he said.

As Orszag moved into the spotlight, his mentor receded from it. In August 2010, Rubin quietly took a job at Centerview Partners, a boutique investment firm co-founded by Democratic fund-raiser Blair Effron.

Orszag finds his new job to be a refreshing break from the bruising political battles in the White House. He’s been advising Citi’s traders on economic trends, working from Citi’s Greenwich Street trading floor, while spending most of his time learning the art of deal-making as a corporate adviser. “I want to do this new stage of my life for a significant period of time,” he told me. “When I was thinking about it at the time [of taking the job], I was thinking something like at least five to ten years.”

One cost of the vast disparity between the pay on Wall Street and everywhere else is that, all other things being equal, Wall Street gets more than its share of the good minds, and many of those it doesn’t control outright, it manages to influence—that’s the American system.

Orszag told me he doesn’t know yet how the system could change. His tenure at Citi, he said, may give answers. “Look, there is an ongoing debate. I don’t have the answer,” he said. “I’m going to exercise some modesty in terms of knowing exactly what to do about it. Over the next few years, I’ll have a better sense of how these incentives work.”

Even a man as smart as Peter Orszag may find it hard to learn that lesson in his current classroom.