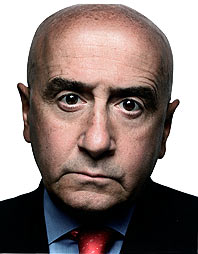

Dick Grasso was hanging out at his spacious Locust Valley home, as he does most mornings these days, when the news hit: Hank Paulson, the head of Goldman Sachs, had been tapped by President Bush to be Treasury secretary. For Grasso, this was a double insult. First, this was a job he was supposed to have been on the short list for, before his ouster as chairman and chief executive of the New York Stock Exchange in 2003. Back then, Grasso was basking in a heroic glow for quickly reopening the stock exchange after 9/11.

Second, there was the fact that Paulson, a former NYSE board member, had led the charge to have Grasso removed after it emerged that he had stashed away a pay package worth $187.5 million. That, in turn, led to the predicament that Grasso has been stuck in ever since: a lawsuit filed by New York State attorney general Eliot Spitzer to recover a chunk of the $140 million that Grasso was paid in 2003, now scheduled to go to trial on October 30.

In the not-so-distant past, Grasso didn’t have many nice things to say about Paulson, referring to him at one point as a “snake” for secretly plotting his overthrow. But that was the old Grasso. The day after Paulson’s nomination, the new Grasso called his former nemesis to congratulate him. Despite a deluge of well-wishers, Paulson answered the call, and the two chatted for about five minutes. Paulson at one point remarked that the Spitzer suit should have been settled long ago. Grasso just laughed, wished Paulson good luck, and hung up.

According to a source at Goldman, Paulson was surprised by the call, but he shouldn’t have been: What made Grasso so effective for so long on Wall Street was his ability to put aside personal grudges in favor of institutional well-being. This time, of course, the institution is himself. The new Grasso is trying to move beyond bitterness and use his considerable skills as a salesman to make the case for his professional comeback. Whatever it might turn out to be—“Maybe it will be something in financial services, maybe not,” he says vaguely—burying the hatchet with the next Treasury secretary is certainly a meaningful step in the process.

More than that, though, Grasso is intent on proving to his critics—including not just Paulson, but all those NYSE board members who voted for his ouster after the pay package was first revealed and the chorus of detractors who have emerged since—that they were wrong to throw him out of office, wrong to suggest that he wasn’t worth the money, wrong to imply there was anything sneaky in the way he amassed it. “Being chairman of the stock exchange was the best job I ever had and the only job I ever wanted,” he says. “But having the experience of being thrown out the door the way I was means I have to come back. Had I retired in the normal way, maybe things would be different. But I was drop-kicked out the door, and now I have to prove that my career wasn’t a fluke or an outlier, that I really do have some talent.”

Of all the corporate downfalls of the past few years, perhaps none has been as tragic as Grasso’s—if for no other reason than it could have been so easily avoided. Grasso’s rise was the kind of success story that people like to believe in. He started as a clerk at the exchange in 1968, a zhlubby underachiever in thick glasses and a cheap suit, and by the time the size of his compensation package leaked in the spring of 2003, he was the unrivaled king of “the Club,” as the exchange is known. Despite his stature, though, it was still shocking for many to discover just how much he was making—more than $30 million in 2001, most of which was deferred into his retirement account. Grasso was attempting to collect much of this account as he negotiated a new contract.

Within a few months of the leak, Grasso’s career unraveled. On September 17, 2003, exactly two years from the day he triumphantly reopened the stock exchange after 9/11, a sullen Grasso was caught on-camera leaving the Club for good.

The conventional wisdom on Wall Street at the time was that Grasso would be allowed to keep his money and quietly slip away. After all, he hadn’t stolen anything. But that’s not what happened. New leadership at the NYSE launched an investigation into his pay package, produced a report that was highly critical of him, and handed it over to both the Securities and Exchange Commission and Spitzer. Even though the SEC was the stock exchange’s primary regulator, and its new chairman, Bill Donaldson, was no friend, the commission decided against intervening. Spitzer had other ideas. He launched his own inquiry and charged Grasso under a little-known state law that says that the officers of not-for-profits must be compensated in a “reasonable” fashion.

Grasso was led to believe that he could settle with Spitzer if he returned $50 million. Later, that figure rose to $100 million, though no formal negotiations ever took place. The thinking on Wall Street was that Grasso would make a deal with Spitzer and avoid all the negative publicity, not to mention the legal expenses and the very real possibility of losing at trial. This would be the prudent Wall Street custom, and Grasso had an even greater incentive to stick to it: A judge, acting on a jury’s guilty verdict, could conceivably force Grasso to return the full $140 million, even though he has paid about $60 million in taxes.

But at great risk to both his already damaged reputation and possibly his own financial security, Grasso has chosen to fight. A settlement, he says, would be an admission that he did something wrong. “This is about my name,” he says. “It’s about my kids’ name. How would it look if I settled? It would look as if I did something wrong, and I didn’t.”

Grasso isn’t the only one concerned about his reputation, and people close to him say his behavior is best explained by his relationship with one man, Kenneth Langone. The head of the exchange’s compensation committee since 1999, the 70-year-old Langone is a large, boisterous man who amassed a huge personal fortune during a long career on Wall Street. He is now also facing charges from Spitzer for allegedly “deceiving” the stock-exchange board about an $18 million chunk of Grasso’s pay package. Langone not only has denied the charge but also has engaged in a furious war of words with the attorney general. There is genuine anger on both sides; at one point, Spitzer told Jack Welch that he wanted to “put a spike through Langone’s heart.” Langone has fought back by, among other things, bankrolling the long-shot campaign of Tom Suozzi, who is challenging Spitzer in the Democratic gubernatorial primary.

Langone has also put Grasso on notice not to settle the case, at least until he can clear his name. “I told Grasso if he settles, our friendship is over,” Langone told me and just about everyone else on Wall Street. Grasso has taken the message to heart. The last time he suggested settlement—in a stray comment made to CNBC last summer, just before a deposition—Langone got extremely angry with him, and Grasso quickly backed away.

Why exactly is Grasso so loyal to Langone? One plausible theory is that Grasso is counting on Langone’s help when he strikes out on his own and can’t afford to burn such an important rabbi. But it may come down less to what Langone will do for Grasso than what he already has done. Langone was Grasso’s greatest champion at the exchange, never backing away from his position that Grasso earned every penny of his salary. “It’s not that Kenny is covering his own ass because of his role; he really believes Grasso was worth the money,” says one Wall Street executive.

Langone officially scoffs at the notion that he won’t let his friend settle with Spitzer. “Oh, yes, I have a Svengali-like effect on Grasso,” he says with a laugh. But he won’t deny that he badly wants the case to go to trial, where he can confront Spitzer in public. And that means he needs Grasso in the fight as well.

During his eight-plus years atop the exchange, Grasso was beloved for a very obvious reason: He helped every major Wall Street firm make a ton of money. When he took over, the exchange, based on actual human traders, was thought to be an anachronism, sure to be eclipsed by the kind of electronic trading that the nasdaq offers. But Grasso tirelessly made the case that people could make an equally efficient and reliable market, overcoming advocates of electronic trading like Paulson. The biggest Wall Street firms, including Paulson’s Goldman, subsequently sunk billions of dollars into purchasing the specialist firms that do the actual trading on the floor. Grasso in turn became the custodian of their huge investment. “No one knows his product better,” James Cayne, the CEO of Bear Stearns, once told me.

“I was drop-kicked out the door,” says Grasso, “and now I have to prove that my career wasn’t a fluke.”

Grasso knew his product so well that most of Wall Street’s top brass did not wish to interfere with his management of the exchange. Grasso had to coax people like Cayne and Paulson to become board members, because compared with their day jobs, overseeing the exchange was a tedious chore. It’s fair to say, especially in light of what happened, that they didn’t always pay the closest attention to what was going on.

Until, that is, Grasso’s pay package began to cause a stir. For years, Grasso’s pay had been among the most closely held secrets on Wall Street. His compensation was set by a committee, headed by Langone, who took the job at the height of the bull market, when everybody was getting rich off Internet stocks and executive compensation had dimmed as a matter of public concern.

In the summer of 2002, Grasso began making noises that he wanted to cash in his retirement package when he renegotiated his contract. This was the fateful decision that would end up destroying his career, and it’s still not entirely clear what inspired it. Grasso told me that he simply wanted to “control [the money] more directly,” as he put it, so he could dole it out to the various charities, such as cancer research, that he and his wife have been active in for years.

That answer doesn’t entirely wash. If he thought he needed more direct control of the money, why had Grasso willingly deferred much of his salary into the retirement accounts in the first place? During one of our conversations, Grasso offered a more blunt explanation: He took the money because he earned it, plain and simple. “I never told these people what to pay me. I was never in the room when they discussed my compensation. They decided to pay me what they did because they thought I was adding value.”

To this day, Grasso’s decision to take the money is viewed as a grave miscalculation. Paulson told me during our interview that he virtually begged Grasso not to do it. In his deposition, he added that while Grasso gets an A-plus for his work as CEO, he gets a C or a D as chairman because he didn’t understand how taking the money would hurt the exchange. It is easy to understand why Grasso didn’t listen to Paulson; the two had been at odds for years over the issue of electronic trading. But someone Grasso did trust, a board member and a consistent supporter of his, William Summers, the then-chairman of McDonald Investments, told him virtually the same thing. Summers believed Grasso was worth the money and later voted for him to stay at the exchange, but he was concerned that it would simply look bad if Grasso raided his own retirement account in advance of his actual retirement.

So why did he do it? Clues can be found scattered throughout the depositions and interview summaries from Spitzer’s investigation as well as a separate probe completed by the New York Stock Exchange. In these documents, Grasso’s big concern appeared to be the possibility that a future board of the stock exchange might be swayed by the growing public disgust over excessive executive pay and think twice about letting him walk away with such a huge retirement package. This may have been a reasonable fear on Grasso’s part, but was it worth the gamble of trying to take it early? If he had served another three or five years as head of the exchange and then victoriously retired, would a board have had the guts to renege on his retirement deal? And if for some reason it did anyway, he probably would have had the good reputation to fight them for the full package.

Whatever his motivation, Grasso needed the approval of the compensation committee to access the retirement account, and when he went to the committee for it, the end came fast and hard. Two new committee members, Cayne and Larry Fink, the head of money-management firm BlackRock, got wind of Grasso’s intentions, and they hit the ceiling. Though both had been on Wall Street for years, earning huge salaries themselves, they had no idea how much Grasso was making, and after seeing a document listing some of Grasso’s retirement savings, Fink confronted Langone, asking, “What the fuck is this?”

Still, even as tension was mounting behind the scenes, the board, including Cayne and Fink but minus Paulson, who was off bird-watching in Brazil, voted unanimously to let Grasso have the money and also to extend his contract through 2007. But when the size of the pay package leaked to the press, the board panicked. Grasso’s allies deserted him, and Paulson led the charge against him. He claimed he had no idea exactly how much Grasso was earning, even though he had sat on the compensation committee since 2001. One reason may be his lousy attendance; in recent depositions, Paulson has conceded that he both failed to attend meetings where the money was discussed and didn’t read correspondence from Langone on the matter.

But it wasn’t really the money; Paulson said he was concerned about what he constantly referred to as “optics”—Grasso’s decision to take so much money simply looked bad. “Retirement money is supposed to be used for retirement, and Dick wasn’t retiring,” Paulson told me during one interview.

Among the charges levied at Grasso by Spitzer is that he “rigged” the system by placing his good friend Langone at the helm of the compensation committee and packing the board with lackeys. On the first point, Grasso maintains that although he always had respect for Langone, they didn’t become close until 9/11, when they worked together to reopen the exchange. As for the other, Grasso says it’s foolish to believe they were his puppets. “If I rigged the system, why would I have wanted these people on the board?” he asks. “Did I have the power to control Hank Paulson or Jimmy Cayne or the rest of these people? Give me a break.”

A few weeks after he was fired, Grasso and I went to lunch. He wasn’t looking quite like himself then. He had grown a beard, and his usually finely polished head showed signs of stubble. He looked like he wanted to give up, and as we discussed the media coverage, he plaintively expressed a desire for it all to end.

More recently, Grasso’s recovered his confident, aerodynamic look (he shaves his head himself now, he says, because the barber he always went to is around the corner from the exchange). He is clearly not happy about the context in which his name is often invoked these days. About two years ago, one of his daughters told him that a professor in her business class at Bucknell University cited him as a prime example of overpaid corporate executives. Grasso was livid but not as livid as Langone, a 1957 graduate, who has given so much money to the school that it has named an athletic facility after him. Grasso says he had to persuade Langone to refrain from making a formal complaint to the school.

Unlike most Wall Street executives, Grasso doesn’t golf or play tennis. He works out with weights occasionally, but he has no real hobbies, other than cooking dinner for his family on Sunday nights. When he was chairman, Grasso could be seen around town at some of New York’s most exclusive restaurants, always with clients of the exchange or business associates. Recently, I ran into him at Campagnola restaurant in Manhattan sitting down for a quiet dinner with one of his daughters. He comes into the city occasionally, riding the Long Island Rail Road rather than the chauffeured truck that used to take him everywhere, and spends much of his time at home, with the television tuned to stock-market news. He has time for the kind of errands he never did before, like driving his son to work.

Grasso concedes that starting over will be difficult, but for that he doesn’t blame Spitzer so much as John Reed, the former Citigroup CEO who replaced him as NYSE chairman. Grasso says Reed committed two unforgivable acts: He made comments to the press about Grasso’s pay that Grasso believes are defamatory (and for which he is suing Reed). And then he enticed Spitzer to take the case. Because of this, Grasso says, he is untouchable in the business world until the legal proceedings are done. Meanwhile, Grasso confirms that he’s doing some work for Joe Grano, the former chairman of UBS PaineWebber and a close friend, who has started his own private-equity firm. “I’m helping Joe with some of my contacts,” he says. He’s also helped former police commissioner Bernie Kerik with his private security firm; despite Kerik’s own recent legal difficulties, Grasso has not cut off ties to him and still calls Kerik a friend.

As with Paulson, Grasso has recently softened his public remarks about Spitzer, perhaps looking ahead to when the A.G. will be governor and even less of a good person to be enemies with. The fact is that Grasso and Spitzer were allies not so long ago. When Spitzer was investigating Wall Street research practices in 2002, he enlisted Grasso’s aid in getting the big brokerage firms to agree to a settlement, then announced the deal at the stock exchange, giving Grasso top billing at the press conference.

Even after the story broke about Grasso’s pay, Spitzer showed support. In May 2003, the men ran into each other when they both testified before the U.S. Senate Banking Committee about corporate scandals. Before they sat down, Spitzer spotted a newspaper article with Grasso’s photo and turned to Grasso with a smile and said, “Nice picture.” Several months later, when Grasso’s contract was extended by the board, Grasso says he had a conversation with Spitzer in which Spitzer said “glad to have you around” for a while.

Nowadays, of course, Spitzer is making Grasso’s life miserable. The A.G.’s staff says the investigation has shown that Grasso used the exchange as his personal piggy bank. They say he charged the exchange for everything from pretzels to expensive dinners to flowers he once sent to Langone’s wife. Though Grasso won’t attack Spitzer directly, he accuses the lead attorney on the case, Avi Schick, of playing dirty and leaking personal e-mails to the press, as well as other information that suggests his family took advantage of perks from the NYSE.

As the personal becomes mixed up with the political, the pressure on Grasso to settle grows. How much dirty laundry is he willing to see aired? What other allegations could emerge at trial? “They think by sleazing me they’re going to get me to settle,” he says. “But it has only strengthened my resolve.”

For the past year, the former members of the stock-exchange board, including some of the most powerful men on Wall Street, have spent hundreds of hours giving depositions about what they knew, what they didn’t know, and what they wish they could forget about Grasso’s pay package. Resentment over the whole drawn-out affair is growing and could well flare up at the trial. Fink verbally attacked an NYSE attorney who he thought was asking questions in an inappropriate tone. Cayne blew up when Schick asked the same question six times. “You got to be fucking kidding,” Cayne exploded.

In what they hope will increase pressure on Spitzer at the very moment that he wishes to focus on the governor’s race, both Grasso and Langone have made clear their plan to call each board member to testify during the trial, something that officials at Goldman are dreading as their former CEO starts his job at the Treasury Department. In late June, Grasso made a move to ensure that Paulson will testify in the case. Grasso’s attorneys sent out twenty “trial subpoenas” to Wall Street executives who sat on the NYSE’s board of directors, but Grasso concedes that his main reason was to lock in Paulson as a witness. “There is no way this case should have gone this far,” laments one senior adviser to Paulson.

If there’s been anything enjoyable for Grasso in the past three years, it’s been watching his enemies sweat. Grasso attended some of the key depositions, including Paulson’s and Reed’s. Grasso’s attorneys grilled Reed for two days. When it was finally over, Reed, visibly exhausted, walked up to Grasso to exchange a kind word. Grasso shook hands with Reed, who remarked how difficult the questioning had been. Grasso was unmoved, telling him, “It’s nothing personal, John. It’s only business.”

The Grasso Gang

Once upon a time, everybody was Dick Grasso’s friend. And if his comeback succeeds, everybody will be again. (Except maybe John Reed.)

Hank Paulson

The former Goldman CEO and newly appointed Treasury secretary clashed with Grasso over the years—then helped usher him out the door when trouble started.

John Reed

The former Citigroup CEO replaced Grasso as chairman of the stock exchange and then contacted the attorney general.

Eliot Spitzer

Though they were once allies, the attorney general is trying to force Grasso to return as much as$140 million of the money he earned as stock-exchange chief.

Kenneth Langone

While other supporters deserted Grasso, the Wall Street veteran and former stock-exchange board member has always maintained that Grasso was worth his huge salary.

Bernard Kerik

The disgraced former police commissioner grew close to Grasso after 9/11, and the two have discussed doing business together.