In the Azekka Room at Le Parker Meridien in October, the elegant face of global capitalism was on display—svelte women who speak flawless but foreign-sounding English, men in tailored suits and plastic-framed glasses with fashionably disheveled hair. They were here to take the measure of John Thain, CEO of the New York Stock Exchange, and Jean-François Theodore, head of Euronext, an agglomeration of European exchanges with which Thain was hoping to merge the NYSE. The event evoked a kind of raceless, classless, genderless Utopia, like Star Trek, but with accents. It was, perhaps, a glimpse at the global future into which Thain is leading his exchange.

Then, after the panel, the past, hefty and bald, stood up. “I have a question for Mr. Thain,” said a man named Stephen Sax. “I represent many brokers on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange,” Sax continued, before launching into a passionate monologue about how the proposed merger, along with Thain’s efforts to automate trading, could put him and his colleagues out of work. This, he said, would be a loss not just to the brokers but to all of international finance.

About 90 seconds in, the moderator interrupted to ask if there was a question embedded in his comments. The room full of bankers began to titter.

“The question is,” Sax said over the din, “with the costs going up on the floor of the exchange for the floor brokers, and a number of people being laid off on the floor, the question is, will that, you know, be a concern maybe that can be addressed?”

This was capitalist comedy; the crowd was now in full-throated guffaws. This guy who looked like he stepped right out of a David Mamet play wants to know if John Thain will save his job. And he’s not the least bit embarrassed about it!

Thain’s earnest reply silenced the laughter. “Well, first of all, I believe the answer is absolutely yes. Because I also believe there is value to the floor, to the auction process … ”

Thain was polite, amiable, and validating, but there was not a person in the room who didn’t think Sax and his brethren would eventually lose their jobs. It was entirely in keeping with Thain’s modus operandi, which has always been to give the coming technocracy a human face. During his tenure at Goldman Sachs, where he rose to the company’s second-ranking position, colleagues took to calling him “Thain the Humane.”

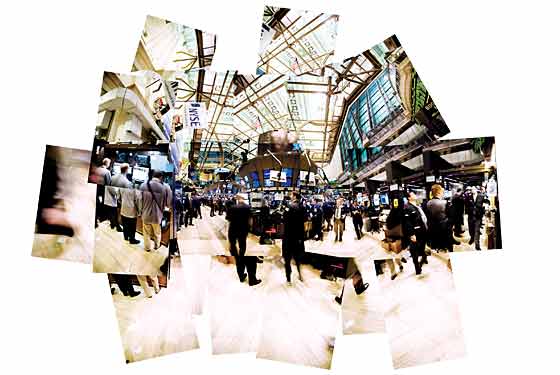

Since taking over for his scandal-racked predecessor, Dick Grasso, in 2003, Thain has transformed what was once an insular, semi-private club into a modern, public corporation. He’s introduced technology that allows investors to trade stocks with zero human intervention, dropping the average execution time from about fifteen seconds to as little as 300 milliseconds. And thanks to a recent vote of confidence from the shareholders of Euronext, he’s on his way to taking the operation abroad.

Wall Street had come to regard Grasso as a fast-talking Luddite who was rapidly turning the NYSE into a 46,000-square-foot museum, but his successor has reversed course. Thain has introduced more major changes in his three years as CEO than the Big Board underwent during its previous 211 years combined.

It is difficult to overstate the sense of crisis that prevailed at 11 Wall Street when Thain came aboard in 2004. Most obvious was the scandal surrounding Grasso’s outsize pay package, but the problem was bigger than that. Investors had begun to see the exchange as a black box into which various middlemen stepped to line their pockets. Grasso, who had a reserve of credibility, having worked his way up from clerk to CEO over a period of 35 years, had never been able to bring himself to confront the floor traders in the interest of modernization. It didn’t help that in the midst of this the Securities and Exchange Commission had announced it was investigating seven of the NYSE’s specialist firms. Specialists are the floor traders whose job it is to ensure that stocks trade smoothly, which means they buy when no one else is buying and sell when no one else is selling. The SEC suspected the specialists of trading on privileged information at the expense of less-connected investors.

This was bad news not just for the exchange but for the city itself. The exchange is still the largest, most-liquid stock market in the world, which confers enormous advantages on the local economy. Many of the city’s roughly 200,000 securities-industry jobs wouldn’t exist but for the prominence of the local stock market. Neither, in turn, would hundreds of thousands of other jobs: A 2005 report by the state comptroller’s office found that each new Wall Street hire creates three additional jobs in the New York metro area.

The news got worse once Thain set up shop in his sixth-floor office. Profits fell 50 percent during his first year on the job. Most of the hit involved the millions of dollars in legal fees the exchange had run up trying to reclaim money from Grasso and a marketing blitz aimed at putting the scandal behind it. But few were giving the NYSE the benefit of the doubt. The going rate for a seat on the exchange—that is, the franchise that entitles its owner to operate on the floor—had plummeted to about $1 million from $2.7 million in 1999.

Somewhat perversely, it was precisely this mess that had attracted Thain to the job. Thain’s final years at Goldman had been an exercise in dignified leadership. He was the senior-most Goldman official in New York on 9/11, and former colleagues still rave about his handling of the crisis. “I do remember thinking that, after 9/11 … if I could pick any one person to sit in that seat, I would have picked Thain,” says Dan Neidich, then a Goldman partner. “He not only saw big-picture, but he knew all the details.” His résumé glistened with the affirmation of elite board membership: MIT (his alma mater), Howard University, New York–Presbyterian Hospital. Thain had been so compelled by what he calls the “quasi-public service” aspect of the NYSE job that he’d agreed to take a $16 million pay cut from the $20 million he made in his final year at Goldman. (“I certainly didn’t do it for the money,” he told me.)

From Thain’s perspective, the NYSE’s problem wasn’t difficult to diagnose. When at Goldman, he’d been critical of the exchange’s uncanny knack for holding off modernity. Thain is an engineer by training. He was particularly galled by the snail’s pace of trading, especially given that a new breed of electronic exchanges had moved in aggressively on the NYSE’s turf. These exchanges traded stocks at the speed of light, rather than the speed of human typing, which didn’t seem like too much to ask of a 21st-century institution. He began to think that the exchange’s best hope was to acquire one.

In January 2005, Thain invited Gerald Putnam, the CEO of Archipelago, one of the most successful of the new exchanges, to lunch at the Goldman executive dining room. At first glance, Archipelago seemed like an odd choice for an acquisition. Ever since he’d founded it in 1996, Putnam had missed few opportunities to taunt the NYSE. He bashed the exchange as a dinosaur and boasted that Archipelago had “pretty much kicked their butt” in new market niches. Putnam once even hired a songwriter to help express his loathing for the specialists. One particularly moving passage went “Joey the Specialist/Seems to have all the good luck/He’d penny his grandmother/Just to make himself a quick buck.”

Personally, too, the men seemed unlikely collaborators. Thain was mild-mannered, modest, circumspect. He’d joined Goldman out of Harvard Business School in 1979 and spent the next two and a half decades methodically climbing the corporate ladder. He’d pass his spare time holed up in his Rye, New York, home. Until this July, when he purchased a Park Avenue duplex listed at $27.5 million, Thain seemed remarkably devoid of extravagance. Putnam, by contrast, arrived on Wall Street as a broker in 1981 and proceeded to shuffle from job to job over the next seven years—twelve firms in all. He could be volatile, rash, profane. The New York Post once reported that he’d decorated the walls of his office with pinups of nude women—Pamela Anderson was among his favorites.

But Putnam was above all a pioneer, and he had several things Thain needed: a lightning-quick trading technology, and a growing business in high-margin products like futures and options. (Exchanges make money by charging companies listing fees and by taking a cut of each trade; the cut is much higher for proprietary products, like futures, in which they have a monopoly.) “Arca,” as it’s called on the floor, was also a public corporation, meaning that the acquisition could simultaneously make the NYSE public, too. Perhaps most important, Thain believed his staid, self-satisfied institution needed a shake-up if it was going to survive. Arca’s bomb-throwing ethos seemed like the perfect antidote.

Thain and Putnam announced the rough outlines of a deal in April 2005. The newly merged New York Stock Exchange Group began offering shares to the public (ticker symbol: NYX) on March 8, 2006. By the end of the first day of trading, an NYSE Group share was worth $80, bringing the company’s market capitalization to a jaw-dropping $12.6 billion.

Among other functions, the NYSE is a ceremonial destination on a par with the White House, or Disney World. There’s a waiting list several hundred companies long for the privilege of ringing the opening bell, and each CEO or luminary who does so leaves a souvenir. Thain’s office is filled with bric-a-brac. On the far wall is a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf stuffed with trinkets: several autographed basketballs (the NCAA champions typically stop by), a racing helmet from Nextel, a nascar sponsor.

To the left of the door is a guitar autographed by Jimmy Page. It’s a memento from the day last year when the Warner Music Group went public. “He played the guitar section of ‘Whole Lotta Love’ and timed the final chord for the bell,” Thain says, with a rare gush of enthusiasm. He’s an unpretentious man with a flat midwestern manner. He wrestled in college, and looks as if he could still make weight.

If nothing else, the sociological distance between Thain and the average floor broker or specialist is about as far you can get between any two people on Wall Street. Thain hails from the tiny Illinois town of Antioch. “I did not grow up in an upper-crust, aristocratic background,” he tells me. “I went to a public high school.” But with his Goldman pedigree and his Harvard M.B.A., he is emblematic of the class of achievers who first began flocking to Wall Street during the sixties.

The floor, on the other hand, is home to the sorts of hustlers who’ve occupied a hallowed place in the finance industry for generations. They are, almost to a man, white ethnics—Italians, Irish, Jews. If you were to press them, they’d probably tell you their first read each morning is the New York Post, not The Wall Street Journal. “I didn’t get a 1600 on my SAT,” one floor denizen tells me. “My business is to make money off my own wits.” These are people who regard Goldman Sachs as a force for evil, and Thain sensed they were prepared to make his life difficult. “There was a little bit of the concern of Goldman Sachs ruling the world … was I a Trojan horse sent over here?” he says. “And so convincing the members that I was here only to help them, to act in their best interest, it did take some time.”

To the floor, the Archipelago deal looked a lot like the final close. The more electronic trading, the floor reckoned, the fewer humans you’d need. That in itself might not have been a huge problem for Thain. The economic history of the last 150 years can roughly be summarized as one long march by machines into terrain previously held by human beings (a march financed by Wall Street and cheered on the floor of the NYSE). Fortunately for the John Thains of the world, rarely have the humans put up much of a fight. In this case, however, there was a wrinkle to complicate the Marxist analysis: In addition to being laborers, many of the humans were also owners of the exchange, by virtue of owning their seats. Which meant that all the fear and loathing of the coming change—combined with a sense that the terms of the merger were far too generous to Arca—could have effectively nixed the deal. “I can’t tell you how many attempts had been made during my years and prior to merge [the various exchanges],” says former SEC chairman Arthur Levitt of his tenure at the American Stock Exchange. “The efforts were … really killed by the floors.”

Thain’s eventual response to the anxiety on the floor was some parts ingenious, some parts obvious: a hybrid trading system—fittingly dubbed “Hybrid”—that gave customers a choice. If they preferred humans, they could still use the old floor-based system. If they preferred to trade electronically, they could use the exchange’s new souped-up technology. The system’s logic is hard to refute. Suppose you want to sell 10,000 shares of an obscure stock that trades only every two weeks. If you try to sell it today, the price may effectively be zero, since there are no buyers. The advantage of humans is that they can usually scare one up. On the other hand, brand-name stocks like IBM and GM have millions of constantly traded shares. For these stocks, there’s no reason to forgo the speed of electricity.

That Thain succeeded at threading this needle has surprised no one from Goldman. “One of the things about being bright is that you can sometimes see a solution that is simple and elegant,” says Fred Eckert, an early mentor. “He’s always been like that … I think he was one of the three or four smartest guys we hired during the twenty years I was there.”

More surprising is that Thain’s achievement has been hailed in less naturally sympathetic quarters. Frank Christensen is a member of the “Buttonwood Group,” a fraternity of seat owners who’ve spent decades on the floor. Christensen says there was genuine queasiness over the Hybrid plan, but Thain convinced the group it was the only way to ensure the exchange’s survival. “He put everybody at ease,” Christensen says. Thain even won converts among the brokers who had no ownership stake—which is to say, the people who had nothing to gain, and everything to lose, from the merger and IPO.

Not long ago, I e-mailed Dick Grasso’s lawyer to arrange an interview. I sent the e-mail at 3:40 in the afternoon. By four, I had answered the phone to hear Grasso’s high-pitched gravel voice on the other end of the line. Prior to the scandal over his nearly $200 million compensation package in 2003, Grasso’s tenure at the exchange was marked by a conflict between large institutional clients—mutual funds and investment banks—who demanded a faster, more efficient exchange, and the brokers and specialists on the floor, who saw Grasso as their protector. Grasso, to his credit, had taken some tentative first steps down the road toward automation. But he is widely seen as having dragged his feet on the matter in deference to the floor. Now, however, Grasso was at pains to get himself on the right side of history. “I think [Thain] has done a terrific job,” he told me. “The Archipelago deal created a viable alternative to the floor. He took the strategic direction of giving the choice of execution to the customer.”

Thain has always worn his ambition lightly—the kind of guy who managed to get the big promotion without looking like he was gunning for it. But the ambition was there nonetheless. “He was a comer,” says Eckert, who says fellow partners viewed Thain as a future leader of Goldman only five years into his tenure there. To this day, friends and former colleagues hint at bigger plans—maybe even a tour as Treasury secretary. So it would be hardly surprising if there were scenes from Thain’s past that he would prefer to keep quiet.

In fact, there is one particular episode that doesn’t quite jibe with Thain’s record of earnest menschiness. In 1998, Goldman was at a crossroads. The firm had entered a nasty internal debate over whether to take itself public, and the Goldman executive committee was deadlocked. Then-CEO Jon Corzine strongly favored the move, as did the firm’s two vice-chairmen, Roy Zuckerberg and Bob Hurst. Arrayed against them were firm president Hank Paulson, the current U.S. Treasury secretary; John Thornton, the firm’s investment-banking boss; and Thain, who was then the firm’s chief financial officer.

In June, a vote of the Goldman partners broke the stalemate at the top of the firm. Corzine had triumphed thanks to a grassroots campaign that saw him undertake a global goodwill tour in search of support. But to the careful observer, there were signs of weakness. Above all, the skeptics complained that Corzine was constantly “getting ahead” of the executive committee, a perception his IPO crusade had reinforced. Corzine was also in the habit of having “unauthorized” conversations about merging Goldman with other Wall Street firms. Later that summer, when Corzine dragged Goldman into a bailout of Long-Term Capital Management, the massively cratering hedge fund, the dissidents had another powerful data point.

Thain created an uproar when he declined to renew the contract for the beloved floor barber. “How many people do you know who have no remorse?” asks one floor veteran. “No remorse and no empathy?”

Thain had been a Corzine protégé throughout much of his career. It was Corzine who’d overrode objections to make Thain CFO in 1994. And it was Corzine who’d landed Thain a spot in the firm’s leadership. “[Corzine] was one of his sponsors to move him up to the executive committee,” recalls Zuckerberg. The two men became close. Thain would accompany Corzine on ski trips to Colorado. He and his wife, Carmen, would periodically meet Corzine and his then-wife, Joanne, for dinner in Manhattan.

Then, just like that, the old rapport vanished. By mid-1998, Thain had taken to bad-mouthing his old mentor to colleagues. “His line was that Corzine wanted to go public to entrench himself,” recalls one. That fall, Thain, Thornton, and Paulson appeared to reach an understanding: Paulson would make the case against Corzine and the other two would support him for the CEO job. Soon Paulson was ranting about Corzine as though he’d been a lifelong enemy—and in ways that sounded remarkably similar to Thain’s complaints. Goldman’s 85 Broad Street headquarters had become the backdrop for a high-stakes game of Survivor.

The turning point came when Zuckerberg retired in late November 1998. This left Corzine in the minority on the executive committee, and somewhat inexplicably, he neglected to appoint a replacement. “I told Jon, ‘Put someone else on the executive committee immediately,’ ” says one former ally. “He said he could handle it. I said I didn’t think he was right.” After a few more weeks of squabbling, the troika of Thain, Thornton, and Paulson went to Corzine with a fait accompli: Paulson would replace him as CEO, and Thain and Thornton would become co-COOs. On January 11, 1999, Goldman partners received an e-mail from Paulson and Corzine: “Jon [Corzine] has decided to relinquish the CEO title, while continuing as a Senior Partner and co-Chairman of the firm,” it read. Corzine was reportedly so humiliated that during his final weeks at the firm, he would work from a limousine parked outside the Goldman offices rather than risk contact with the traitors inside.

Within Goldman, there have always been two theories about Thain’s role in the coup. The first is that Thain wanted Corzine out so he could eventually run the firm himself. The second is that Thain had been motivated by a sense of duty. He genuinely believed Corzine’s leadership had put Goldman at risk and took it upon himself to save Goldman from the CEO’s worst impulses.

The advantage of the second theory is that Thain had always been a loyal company man. “People liked him, respected him, thought he was a straight shooter,” says a former Goldman partner. “He was not particularly political.” The problem is that there’s little evidence Thain felt Corzine was endangering the firm. For example, Thain opposed the IPO as long as Corzine was in the picture, then personally embraced the offering once he’d left. It was hard to believe Thain hadn’t come to regard Corzine as a rival. (Thain declined to comment on the Goldman shake-up.)

Whatever the case, Thain would never get his shot at running the company. Paulson consolidated power so decisively that many partners wondered if they’d been right to assume it was Thain and Thornton, rather than Paulson, who had masterminded the coup. “In hindsight, I’ve asked myself whether Hank was more the architect … than people believed,” says the former partner. Thain says he turned down the NYSE job several times in 2003 before finally accepting it. Ironically, given the reasons for Thain’s break with Corzine, one of the factors that surely weighed on his mind was that Paulson didn’t look to be going anywhere. “I am the No. 2 person here,” Thain told The Wall Street Journal shortly after accepting the NYSE job. “This is my chance to be CEO.”

Despite the fact that brokers now place orders using handheld wireless devices, as opposed to the more traditional “slips of white paper,” the floor is still littered with debris. Discarded boxes of breath mints, soda-cracker wrappers, straw wrappers, candy-bar wrappers, crumpled-up paper bags. It’s as though people on the floor need evidence they’re still here. Several times, I saw a specialist jot something down on a small piece of paper only to ball it up and throw it on the floor for no apparent reason.

Watching the action on the floor brings to mind the 1973 movie Bang the Drum Slowly, about a fictional New York Yankees team. One of the movie’s recurring set pieces involves a card game called TEGWAR—“The Exciting Game Without Any Rules.” The joke is that there actually are rules. They’re just not evident to the uninitiated, which is why knowing them can earn you a lot of money.

The New York Stock Exchange can feel like one big game of TEGWAR. Two days before Thanksgiving, I spent some time with a specialist named Sean McCooey, who would narrate the various goings-on at his booth for me as they unfolded. McCooey is a trim, fiftyish guy with close-cropped silver hair that matches a smart silver suit. His family has been doing business on the floor of the exchange for generations.

At one point, McCooey paired up a broker looking to buy 68,000 shares of American Express with a broker looking to sell 80,000 shares. You never want to draw attention to a large order, McCooey explains, because other buyers and sellers will move the price on you. So, instead, both men confide their interest to McCooey, who in turn brings them together. Then, in order to round out the “print,” as it’s known, McCooey himself buys the remaining 12,000 shares. What’s in it for you, I ask? “If I don’t buy those 12,000 shares, he’ll look at me like, ‘Why didn’t you buy those shares?’ ” he says. Translation: There may be a time when McCooey needs to unload some shares, and this guy can return the favor.

Not long before the close of trading, McCooey picks up a dog-eared piece of laminated paper and starts writing on it in erasable marker. “Imbalances,” he says, then clips the paper to the side of one of his flat-screen monitors. It turns out McCooey has written down the number of shares of the stocks left to sell at the close. It’s a little like a sign you might see for discounted bagels late in the afternoon at Au Bon Pain. McCooey has clipped it to his monitor so the brokers will notice it as they walk by.

The long-term question facing the exchange is whether the floor can survive in some form. Ask Thain this question directly, and he will tell you the floor is crucial to the 90 percent of NYSE-listed stocks for which trading isn’t especially liquid—which is to say, when it’s hard to match buyers with sellers. The same is true when the market experiences turmoil—that is, when everyone is trying to buy at once, or everyone is trying to sell, and no one wants to take the other side of the trade. “We have many, many stocks that would trade terribly electronically,” he says. “And so as long as the specialists and brokers continue to add value, which they do, I think the floor is viable.”

There is little doubt that Thain believes this. But there is also little doubt that one day, possibly soon, a computer will be able to perform all the functions specialists and brokers perform today—even for illiquid stocks, even when the market is convulsing. “You could write an algorithm that could play at chess, too,” Thain counters when I bring up this scenario. “But the very best people still beat the computers.” True enough. On the other hand, if you were faced with a choice between hiring several hundred people to play chess and buying a single software package that could play almost as well, you’d probably opt for the software. The software doesn’t need health benefits. Or lunch. It’s hard to believe that Thain, the consummate engineer, isn’t heading in this direction.

At times, the praise you hear for Thain on the floor has all the passion of a POW reading a prepared statement. The hybrid system “allows me to represent my customer better,” says Doreen Mogavero, who runs a small brokerage firm with a presence on the floor. “Any time you give the customer more choice, the product you give them is better.” Brokers complain that Thain is pricing them out of existence at the same time he whispers sweet nothings in their ears. Specialists gripe that Thain has cut their commissions, and that promised revenue-sharing arrangements don’t make them whole. Last year, Thain filed papers with the SEC seeking a moratorium on the market makers who do business at the exchange. (Market makers are similar to specialists—they move in and out of stocks to help ensure liquidity.) There may have been legitimate reasons for each move—the market makers can be costly to regulate, for example. But his tactics have raised eyebrows. “There was no due process,” says one floor critic. “We were completely blindsided.” One gets the impression that Thain, in his sober engineering way, has identified what he believes to be the optimal approach to these conflicts: Appear soothing and gracious to your interlocutors—then quietly undermine their cause.

It doesn’t always work out that way. Earlier this year, Thain created a minor uproar when he declined to renew the contract for the floor barber, a 43-year NYSE employee named Gerardo Gentilella. Gentilella had received an annual $24,000 subsidy from the exchange, so it was entirely Thain’s prerogative to let him go. But Gentilella had asked to stick around through the end of the year and work for tips. The brokers and specialists thought Thain owed it to him. Eventually, the backlash grew so strong that CNBC’s Maria Bartiromo, the floor doyenne, called up Thain and asked him to reconsider. Thain said he’d look into it, but, come June 30, Gentilella was packing his bags. “How many people do you know who have no remorse? No remorse and no empathy?” asks one floor veteran.

In the end, of course, it’s hard to blame Thain for doing what any other CEO of a public company would be expected to do—certainly what people on the floor of the NYSE would expect a CEO to do—which is to wring inefficiencies out of his organization to boost his bottom line. The day I visited McCooey on the floor, he was marveling at the recent bull market in NYX stock. The share price was up $8.50 that day alone, to nearly $105. Just three weeks earlier, it had been at $75. McCooey speculated that the rally could have something to do with the Euronext deal. A rival bidder called Deutsche Borse had withdrawn its (stingier) offer for Euronext, and as a final deal-sweetening concession, Thain had agreed to split the new board evenly between the two companies. The merger now looked like a fait accompli.

But there seemed to be something else going on. Earlier in the week, Barron’s had published a provocative story called “Death of the Floor.” The cover of the issue featured a skeleton holding a CNBC microphone while reporting from the exchange. When I’d asked the preternaturally optimistic Sax about it, he began to moan. “The cover story says it all … It’s already too late to save the floor.” McCooey was more even-keeled, but the idea that the market was rewarding NYX stock on the expectation that there would soon be no floor seemed to wear on him, too. “The picture was more offensive than the article,” he told me. “But that’s Barron’s. They’re always negative.” On the balcony behind him, Thain was just then ushering in the prime minister of Iceland and the head of a company called Novator, one of the richest men in Europe. They were about to ring the closing bell.