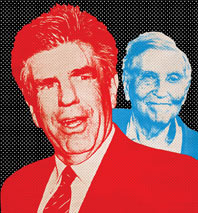

Les Moonves understood UPOD, Tom Freston never heard of it. That’s the only explanation I can think of for why Moonves, the sunny CEO of CBS, is now the toast of Wall Street, and Freston, the defrocked CEO of Viacom, is just plain toast.

On Wall Street we like guys who can “beat the numbers,” executives who set expectations low to the people who make the earnings estimates, who talk about how tough the environment is, and then, voilà, blow those estimates out of the water. That’s playing UPOD, the great game of Underpromise and Overdeliver. No one gives UPOD like Les Moonves. From the first trading day of the year, when CBS split from Viacom, Moonves signaled to the analysts not to expect too much. He wearily described the hand he’d been dealt by Sumner Redstone, a hand with a struggling radio operation, a stumbling outdoor-advertising business, a vestigial theme-park franchise, and, worst of all, an unloved older TV demographic. He couldn’t possibly make the Street’s estimates because he was deprived of the one high-performing asset he thought he deserved: Paramount Pictures. It was enough to make you feel sorry for the perennially tanned and rested exec, and, more important, it was enough to take CBS’s earnings estimates down to where they could easily be beat come the first couple of quarters. Moonves overdelivered immediately. That’s why his stock has become the media stock to own, one that seems to have taken up permanent residence on the new-high list.

Freston, on the other hand, created an almost Olympian standard from the get-go, allowing estimates to be set that were more in line with those typical of fast-growing companies—companies growing much more quickly than say, News Corp., or Disney, or, of course, the snail-paced CBS. Plus, Freston, unlike Moonves, exhibited pride—hubris some would say—as being the anointed one of Sumner, the Cain to Moonves’s Abel. How high was the level of confidence when Freston emerged from Eden on his own? Consider the quotes from this post-creation interview about Freston’s relationship with Redstone: “I have worked for him now since 1987. He’s always been a boss to me who has very much trusted my judgment and given me the leeway to do what I need to do within a certain set of parameters. He has never really been sort of one of these maniacal micromanagers.” Wrong on just about every count! In the end, Redstone wasn’t the forgiving Dalai Lama that Freston described; he was more like the George Steinbrenner who got fed up after a couple of months in second place and sent the manager packing to see if someone else could get the stock into the playoffs.

Don’t believe for a minute that Philippe Dauman will be in charge. Redstone wants to be Rupert Murdoch now.

To me, Freston just didn’t know how to play the Wall Street game, the one that Redstone cut his teeth on and Moonves understood so well. All Freston had to do was say that there were some short-term concerns out there, such as problems with MTV and Nickelodeon, that could be fixed by some aggressive moves on the Web. Had he set the bar low, like Moonves did, he could have beaten the numbers and gotten the opportunity over time to negotiate takeovers of some high-profile Web properties like Facebook or YouTube. That could have funneled a new generation of young customers into Viacom’s ailing cable units and brought instant love from analysts who would have seen the company not as an old media dinosaur but as a new media leader—say, the next Google.

But Freston didn’t do that. And so it didn’t matter that Redstone said publicly, after the split took effect in January, that Freston had a year to build the company. The moment Freston missed his second-quarter estimates, the quarter he had foolishly overpromised on just months earlier, he was doomed. The octogenarian but hardly capricious Redstone looked at not only Viacom’s stock performance compared with Moonves’s stock but also the stock of the successful buyer of MySpace.com, News Corp., and Disney stock—all of which were climbing—and decided his man couldn’t take his company out of the cellar. So he handed the ball to someone else, despite reiterating just a few weeks prior that Freston had the whole year to make it happen. The poor ratings of the MTV Video Music Awards recently, like a shellacking in a home ball game, may have been the last straw that Redstone could handle. You could feel the old man’s humiliation the moment the Nielsens printed for that lackluster night.

Now it looks like Redstone’s back running the company. Don’t believe for a minute that Philippe Dauman will be in charge. Redstone wants to be Rupert Murdoch now. He sees that, with expectations so low (Viacom’s in the position CBS was in when Moonves took over), he can make bold moves without fear of driving the stock lower. What should he do? First, he needs to find a Roger Ailes or Peter Chernin, an older hand who understands the Web and gets the need to show progress while the Web ramps up. As interested as I would be in buying the much-loved Facebook, and as fascinated as I would be at having a crack at cultivating the PC-TV watchers of YouTube (moves that could get college kids, teens, and children hooked on Viacom), I’d buy Electronic Arts first. Why? Because EA owns the 13-to-34 demo, because video games produce successful movies, and because those games will soon be sold on the Web, not in stores, and buying EA would show that Redstone’s got a jump on the technology that will make such downloads happen. What’s more, Redstone can sell embedded ads inside the video games. And as the majority owner of a much lesser interactive-games company, Midway Games, he actually understands this market. Plus, because of the dearth of new gaming systems for EA to run on (Sony and Nintendo have been late in producing new hardware), EA is cheap right now—down twenty points from its high a year and a half ago. EA could be Viacom’s MySpace without the possibility of fickle audiences going elsewhere because EA is the only game in that town, with a proven category-dominating product. Ironically, Freston paved the way for this addition by purchasing Neopets, another game company for younger kids, and one that girls love. Dovetail Neopets with EA and you’ve got boys and girls hooked before they get to college and discover Facebook.

The Street initially reacted negatively to the Freston firing, thinking that Redstone may have lost his mind. Yet, despite the apparent cool Freston displayed in hanging out with the Jon Stewarts and Stephen Colberts of the world, he had lost touch with the college, teen, and youth markets. In one fell swoop, Redstone can get them back with EA. Given that the new video-game hardware ships this winter, EA could immediately add to the bottom line, something akin to what Murdoch was able to pull off with MySpace. Then Redstone can reap the spoils of UPOD and retire as a hero to the Sunrise Senior Living Home for Entertainment Moguls.

James J. Cramer is co-founder of TheStreet.com. He often buys and sells securities that are the subject of his columns and articles, both before and after they are published, and the positions he takes may change at any time. E-mail: jjcletters@thestreet.com.