They come here to toast the dead. Ever since Big Pussy got clipped at the end of season two, the Sopranos cast has convened at Il Cortile, a little joint in Little Italy, to bid a proper farewell to members of the family who’ve been snuffed out and tossed into the purgatory of auditions and callbacks. Whacking parties, they call them. And here they are again, squeezed around a large table that feels suddenly tiny, jabbing their fleshy paws into the air and ordering up the usual.

“I’ll take some veal marsala!” bellows Steve Schirripa, a behemoth of a man better known to Sopranos scholars as Bobby “Bacala” Baccalieri. “Actually, make that a few veals! And some penne arrabiata. Maybe a vodka rigatoni. And let’s get like three carafes of red wine. Oh, and some of that steak! The one that’s not on the menu. A few steaks!” He sighs contentedly before turning to his cast mates. “All right,” he asks, “what do you guys want?”

Tonight’s feast isn’t an overtly morbid affair; the wiseguys are showboating and wisecracking, same as ever. But the sixth and final season of The Sopranos premieres March 12, and something tells me I’m not alone in seeing our gathering for what it is: the ultimate whacking party, the last supper for the last men standing. These are the guys who play Tony’s soldiers, the ones doing the disappearing and racketeering, the other family competing for his love and loyalty. Individually, they may verge on cartoonish, but collectively they embody the show’s more sinister heart. After all, Tony is a surreal figure—an existential brute perpetually examining his actions—whereas his crew is much closer to the real thing: relentlessly amoral, immune to change, a band of sentimental sociopaths that grounds the Sopranos in legitimate mob culture. “They all know that world so well,” James Gandolfini tells me. “I ask for their opinions all the time and trust whatever they tell me about what I’m doing.” More than anything, they provide David Chase, the show’s creator, with a vehicle to express his compellingly bleak worldview: that evil often wins out over good, that the glitch of the human mind may be its insistence on believing otherwise.

As fictional thugs, their roles are tied up in the same cruel joke that makes the show so riveting: Any one of them, at any moment, could wind up dead. “David Chase invented the Big Pussy Rule,” explains Schirripa, “which is that no one lives forever.” Before signing the mortgage on his Tribeca apartment, Schirripa made the rounds, asking if anyone had heard rumors about his being whacked. “I would’ve bought something five years ago, but I thought they’d kill me.”

“Oh, man, it is a constant worry,” chimes in Tony Sirico, who in person comes off a lot like Paulie Walnuts: the sarcastic hostility, the slicked silver wings in his pomaded hair.

“The fact that you don’t know if you’re going to live or die creates an intensity that shows up in the work,” adds Steve Van Zandt, the guitarist of Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band who plays Silvio Dante, Tony’s consigliere.

“I did die!” exclaims Dan Grimaldi, the only member of the crew to be killed (as Philly Spoons) and resurrected (as Patsy Parisi, his twin brother).

Like athletes, the actors concoct rituals they hope will stave off their day of reckoning. Arthur Nascarella, who plays Carlo Gervasi, walks to the show’s set at Silvercup Studios over the 59th Street bridge, no matter the weather. And though he wants as much screen time as the next guy, he knows the risk: “As soon as you start talking a lot, you’re dying,” he says. “You get a lot of dialogue—that’s the end.”

This is Joe Gannascoli’s problem. In one of last season’s more startling moments, his character, Vito Spatafore, was caught going down on another man. “My idea!” he boasts. “It was in a book I was reading. True life, an openly gay mobster.” It gave his role more depth, but given Tony’s stubborn perspective on just about everything, his risk of being clipped is exponentially increased.

When I bring all this up a few days later with Chase, he tells me he’s aware of the irony: that the anxiety he creates in his actors bears more than a passing resemblance to the way Tony manages his workers. “If I call to thank them for a Christmas gift, I can hear it in their voice,” he says. “They’re thinking, Oh, no. What’s he calling for? Is this the end? ” To soften the blow, he’s devised a procedure to deal with the soon-to-be-deceased: He finds the actor at a script reading a month before the scene, calls him into his office, and breaks the news. Since the rest of the cast doesn’t get the script until a few days before shooting, the dead man walking must take a vow of silence. Of course, now all their fates are sealed, regardless of how the writers decide to treat their fictional alter egos, which is the white elephant here in the dining room at Il Cortile.

“Hey, write this down,” Schirripa demands. “Contrary to what a lot of people believe, we are not gangsters. People come up to you and say, ‘Hey, my cousin Johnny is in the can. Don’t know if you know him—little Johnny from Avenue U?’ I’m like, How would I know him? I have a fucking college degree! I’m an actor!”

Throughout the meal I’m bombarded with such clarifications. Makes sense, I guess: No one’s eager to be mistaken for a murderer, and actors are notoriously sensitive about being taken seriously. I’m told a story from a few years ago, when Michael Imperioli, who plays Christopher Moltisanti on the show, was approached by an overzealous fan while vacationing in Lake Tahoe. “This Italian guy, right?” recalls Schirripa. “He’s going, ‘Put me on the show! I’m the best!’ Michael says to him, ‘What the fuck? Have you been fucking acting? I’ve been doing this 23 years!’ ”

Life imitating art imitating life—it’s a vicious cycle. Mistaken identities aside, no one denies that a symbiotic connection has developed between the actors and the characters they play. “There’s a tremendous amount of camaraderie between these guys,” Chase says, “as well as a lot of competition and backbiting. They come to me and say, ‘Why did he get to do this? Why did he get to do that?’ A lot like they are on the show with Tony. And it’s true that when they’re together, a kind of groupthink takes over.”

On any given night you can find them together like this: wedged around a table, drinking chilled Patrón from martini glasses, fighting over who gets to pick up the tab, making maudlin pledges of loyalty. Maybe it’s an impromptu convergence at Pastis, maybe a mellow round of drinks at Dekk, a low-key Tribeca bar that has become their nocturnal headquarters. “Look, we’re seriously happy to see each other,” says Schirripa. “If you think those bitches on Desperate Housewives like each other, then you’re out of your fucking mind.” It helps that most everyone has roots in the tri-state area, with an especially healthy dose of Brooklyn pride among them. “We grew up in neighborhoods with Italian doctors, Italian lawyers, and Italian mafioso,” says Grimaldi, eliciting knowing nods from Max Casella (Benny Fazio) and Robert Funaro (Eugene Pontecorvo). “We knew these people. We’ve been associated with this kind of stuff all our lives.”

Gandolfini, too, brings up the “upper blue collar” bond with his cast mates: “We’re not out to hurt each other,” he says. “If one person steps out of line, we’re going to tell him he’s being stupid, get him back in line. You’re in a circle being stared at, you know? And we all kind of protect each other.” To outsiders, the group is almost impenetrable. “I remember one time, we had someone come in who wasn’t from the same background,” says Gandolfini. “I’m not going to say who. We all knew it wasn’t going to work, and it didn’t.” As for the rest of the guys: “They all just really get it. I don’t have to reach down and pull them up. Ever. If anything, they’re holding me up.”

Indeed. Coming from movies, Gandolfini has never quite been comfortable with the masochistic schedule of television production: shooting up to seven pages a day as opposed to two or three. “In the beginning, he quit every day,” recalls Van Zandt, who for a time was considered for the role of Tony. “He’d say, ‘I can’t do it, it’s too much. Are you out of your fucking mind?’ I’m like, ‘Jimmy, come on now, you can do this.’ ”

But for the most part, it’s Gandolfini who looks out for his cast mates much the way Tony looks after his soldiers. “He plays the boss and is treated like the boss when the cameras aren’t rolling,” says Van Zandt. “It sounds funny, but that’s how it is.” Before filming season five, Gandolfini clashed with HBO over his contract: He sued the network, the network sued back, eventually everyone settled. He ended up making something in the ballpark of $13 million a year. While the press portrayed him as a tyrant, he made a point of approaching all the regular cast members and inviting them to his trailer for a private meeting. Thanking them for their patience and hard work, he handed them each a sizable personal check. (“Enough to buy a nice car,” says Schirripa.) It was all very hush-hush, the sort of gentlemanly gesture Tony would’ve approved of.

With the meal coming to an end, and everyone in a food-stoked delirium, I ask how it feels to be on the verge of death. Fictional, metaphoric death, I clarify. But it’s too late. The festive mood has already turned funereal.

“Why would we want it to end?” Schirripa asks, his voice reverberating off the walls of the restaurant. He’s developing a sitcom with Touchstone, but you never know if that’s going to work out. Sirico, too, is thinking he’ll do some comedy. “Maybe do a Hope and Faith,” he says. “Be Kelly Ripa’s uncle Carmine, out of the can.” But if it was up to them The Sopranos would go on indefinitely.

“Look, we’re not done,” says Sirico. He brings a full glass of wine to his lips, and when he puts it back down, it’s empty. “He’s on the top of the hill,” he says, referring to Chase. “All he can go is down. That’s the way he thinks. We’d all like him to keep going. On and on and on and on. You hear me?”

A few months back, there was a shred of hope: Chase announced that he’d be extending the season by eight episodes—a decision he says was partly motivated by these actors, wanting to flesh out their characters. But he swears the show is really over: He, for one, knows how it will end. Gandolfini is ready to retire as well. “You can’t go too much more into Tony’s psyche,” he says. “He’s really a bridge now, between his family and mob life.” And how about the cast? Do his supporting actors ever encourage him to keep going? “Nah, they don’t put any pressure on me,” he says. “I put a lot of pressure on myself, knowing it’s a good thing for a lot of people.”

So good, in fact, that many of the guys prefer to deny their fates. Maybe it’s the wine, maybe the late hour, but suddenly a lot of silver linings are being manufactured. As the waiters bring a round of espresso, Sirico grabs me by the arm and shoots me the sort of unhinged look—eyes flaring, jaw trembling—that I’ve seen his character give many a marked man before pulling the trigger. “Let me just say this,” he says. “For those of us who survive this year, we have the chance of coming back. That’s profound, you hear that?” His eyes scan his fellow soldiers, one at a time, in a gesture so over-the-top that no one dares interrupt him. “For those of us who don’t survive, there’s no coming back.”

An uncomfortable silence follows. Finally, it’s Gannascoli who timidly raises his hand. “You never know,” he says. “There’s always a dream sequence.”

• Lost Soprano: Lillo Brancato Jr.

• Confessions of a Desperate (Mob) Housewife

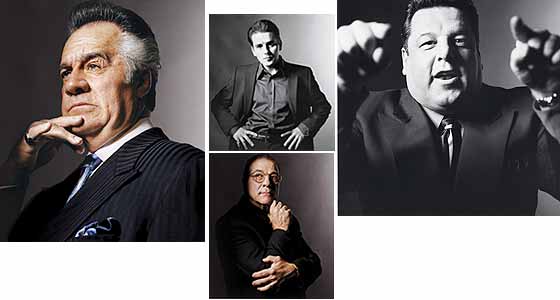

• Blood Brothers:The Sopranos Cast Realize No One Lives Forever

• Six Writers Imagine How The Sopranos Will End