At the end of my career, to have to listen to people say, ‘You lied to us, you cheated, you did this to us!’”—Burt Neuborne is practically pounding his right hand on the table now, momentarily channeling the anger of his accusers—“it hurts,” he tells me, “especially since they are survivors.”

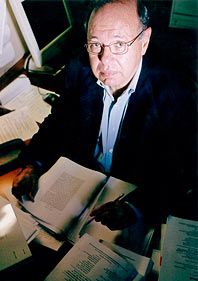

In the dark art of lawyering, Neuborne has always been considered a white knight. He is one of the nation’s leading public-interest lawyers, a defender of lost causes: Air Force pilots who refused to bomb Cambodia in the Vietnam War, the Socialist Labor Party when it wanted to get on the ballot, legal-aid lawyers suing the government. Yet when Neuborne takes up the cause of the little guy, the little guy often wins. Of the twelve cases he’s argued before the Supreme Court, he’s won eight. Now he is sitting in his office at the NYU School of Law, where he teaches, second-guessing his decision to represent the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. The crusading attorney helped to win $1.25 billion for his clients, but some of them now regard him as just another big shot looking out for himself.

The battle is over legal fees. Neuborne is seeking $4.76 million for almost eight years of work representing Holocaust survivors in the distribution of the Swiss-bank settlement for plundering Jewish assets in World War II. Some of the survivors are furious. They thought he had been working for free. They had heard him say so several times, or so it seemed. They were already angry at Neuborne for backing the judge and opposing them—“betraying” them, in their view—in a crucial decision that diverted more than $100 million of that payout to needy survivors in Russia. Now here he is, staking a claim to settlement funds they regard as “holy.”

Elan Steinberg, former executive director of the World Jewish Congress, calls Neuborne’s $4.76 million bill a “moral disgrace,” pointing out that in a similar class-action suit against German industry, Neuborne already made $4.4 million. Menachem Rosensaft, a lawyer and the founding chairman of the International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors, says, “There is a point at which even greed becomes unseemly.” Robert Swift, a Philadelphia human-rights lawyer who also worked on the case—and clashed with Neuborne—says flatly, “Burt did a lot of things here that we would not want to teach our kids in law school.” Others disagree: “In my opinion, he has done a superb job, in the finest tradition of what lawyers should do,” says Michael Bazyler, a Whittier Law School professor who has written about the case. And the dispute has split the Jewish community. Next week, the Anti-Defamation League will give Neuborne its annual American Heritage Award, recognizing his work on behalf of the survivors and others. Gary Rosenblatt, the editor and publisher of The Jewish Week, wrote in a column, “Whatever number ultimately is determined to be fair pay for Neuborne, he should be compensated with a sense of gratitude, not bitterness, and the focus should return to pressuring those governments and banks and other institutions to pay what they have long owed.”

For Neuborne, it is all a giant misunderstanding: “To the extent that the survivors are confused and misunderstood that I would be seeking fees,” he says, “I feel terrible.” The outcome of the Swiss case could not have been more successful, he believes. He spent years as the lead settlement counsel, and the pace was relentless. After collapsing with chest pains in 2002, he worked on his laptop as he was being prepped for open-heart surgery. “After all these years, the last thing I want is for survivors to think that I was not straight with them,” he says. Yet how could anyone think he was donating all that time, he wonders; he certainly wasn’t doing it for his health. “My doctors were so pissed at me for continuing this stuff,” he says. Neuborne sits in his NYU office, arms folded across his chest, as if trying to restrain himself, fulminating. He’s leaning forward now, almost on the edge of his chair, and his voice begins to rise. “Sometimes I think, would I have been better off just staying in my own world … and not having to deal with people who, at the end of my career, call my integrity into question on something that I literally”—he pauses—“almost killed myself working on?”

It has been ten years now since Burt Neuborne suffered what he calls “the worst thing that could ever happen to anybody.” In 1996, his youngest daughter, Lauren, died of a heart attack. She was 27, and Neuborne, then 55, was devastated. His passion and sense of purpose evaporated. “He was beyond a state of sadness,” says his friend, the lawyer Richard Emery. “I was very concerned about Burt’s future.” So Emery staged an intervention. He asked Neuborne to join a long-shot legal assault against a smug and impenetrable target.

The case was about billions deposited by European Jews in Swiss banks for safekeeping on the eve of World War II and never returned. Previous efforts to get the money back failed. But with the remaining Holocaust survivors reaching their final years, momentum was building for one more try. “It was an opportunity to finally get closure for a lot of people who lived through a horrible part of history,” says the class-action attorney Melvyn Weiss, who also worked on the case.

Neuborne attended Harvard Law and worked as a tax attorney on Wall Street before finding his calling in civil-rights and public-interest law. For all his experience arguing before the Supreme Court, he had relatively little in international law and no real involvement with the Jewish community. Still, the more he considered it, the more attracted he was. When she died, Lauren was studying to become a rabbi, a big departure for his family. “She apologized to us for going into rabbinical school,” he says. “We were intensely secular. [My wife] was the director of the now Legal Defense and Education Fund. I headed the ACLU legal program. To the extent that we had a religion, it was the Bill of Rights, and we worshipped it.” Neuborne came to believe that seeking justice for Holocaust survivors would be “extending the arc of Lauren’s life in some way.” And so he entered the case, working for free.

The work was a salvation, at least at first. “A life preserver,” is how Neuborne puts it. He played a starring role during eight hours of oral arguments in federal court—talking so long, he says, “my face hurt.” The Swiss banks waved the white flag. In August 1998, after twelve consecutive days of negotiations, they agreed to the $1.25 billion payout. Neuborne’s work, however, was only beginning.

The settlement was silent on how the money should be divided. This was deliberate. “Everybody punted,” Neuborne says. “Everybody was so pleased to get $1.25 billion that nobody wanted to even think at that point how it was going to be allocated.” And so, in January 1999, five months after the banks capitulated, the judge—Edward Korman of Brooklyn federal court—urged Neuborne to return in the role of lead settlement counsel. It became Neuborne’s responsibility to represent hundreds of thousands of Holocaust survivors covered by the settlement in the crucial decisions about who would get what. The job proved far more complex and controversial than anybody imagined.

Although the settlement compensated Swiss-bank-account holders, there were other groups of survivors who were eligible, including a “looted assets” class—for example, survivors whose gold and jewelry had been seized by the Nazis and fenced by Swiss banks. In a typical class-action case, each class of plaintiffs has a lawyer representing its interests in dividing the settlement. But Neuborne and the judge thought such an adversarial scramble of elderly survivors would be tragic. They developed an alternative: Survivors were asked to accept the settlement—giving up their legal claims to the banks—before they knew what they would get. Neuborne would represent not any one class of survivors but everyone. Of the hundreds of thousands covered by the class action, no more than a few hundred opted out of this arrangement.

Then Judge Korman (largely following the proposal of a special master tasked with devising a plan) decided that the looted-assets survivors would get nothing at all. There were just too many of them, he reasoned, and how could anyone prove which looted assets ended up in Switzerland? Korman ruled that using their $100 million share of the settlement to help destitute survivors would be the “next best thing.” He ordered that 75 percent of the aid for Jewish survivors be spent in the former Soviet Union, where he considered the needs overwhelming; 21 percent would go to other foreign nations. Only 4 percent would be used to help survivors in the U.S. And that’s the root of the trouble.

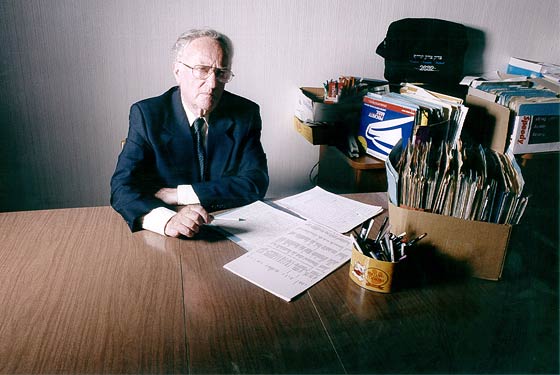

Leo Rechter, the 79-year-old leader of the 1,100-member National Association of Jewish Child Holocaust Survivors, avoided the Nazis by hiding in plain sight. Born in Vienna, he spent much of World War II in Brussels, and because he was blond-haired and blue-eyed, no one suspected he was a Jew. Rechter did everything a young teenager could to provide for his mother and two sisters. He sold bread and old clothing and peddled cigarettes made from discarded butts. Tenacity saved his life, and when he ushers me into his rowhouse in Jamaica, Queens, one night, it becomes clear that that tenacity continues to define it.

After retiring from his position as a bank president at 65, Rechter explains, he volunteered for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation, traveling around the city to videotape scores of survivors’ remembrances. He was struck by how many survivors were in need. “I was appalled that in the richest country on earth, there are survivors who cannot afford their dentures, their medications, their dialysis,” he says. The experience propelled him into his current activist phase. In his dining room are two large bureaus filled with files of the organization’s work. Rechter reaches into one, grabs a folder, and hands it to me. It contains several neatly labeled files: SWISS BANKS CASE, NEUBORNE’S PROMISE, NEUBORNE’S STATEMENTS, AND DISTORTIONS. “In my opinion, what Mr. Neuborne has done is immoral,” Rechter says.

The division of the looted-assets money upset Rechter and the leaders of other grassroots American survivor groups. They saw it as an injustice that so much aid would go to the former Soviet Union, at the expense of poor survivors in the U.S. The case was supposed to be about restitution, compensating victims, but this outcome seemed more like charity. And so they broke from Neuborne, and their lawyer, Samuel J. Dubbin, filed an appeal on behalf of American Holocaust survivors, holding up the $100 million in aid. Months passed without a resolution, frustrating Neuborne and the judge. Korman called for a meeting in his chambers in Brooklyn. Dubbin flew in from Florida; Neuborne trekked in from Manhattan. “The judge took out a yellowed copy of the Times and showed me a story about how hard life is in Russia,” Dubbin says. “I told Korman about the needs in Miami.”

What happened next is bitterly disputed. Dubbin says that the judge admitted he did not realize that the needs of some survivors in America were so great and that Neuborne offered a quid pro quo: He’d help them if Dubbin would just drop the appeal. Neuborne recalls the meeting differently: “The judge told Dubbin, ‘Why are you doing this? Your appeal is worthless’ … I said to Dubbin, ‘I don’t want to embarrass you. Isn’t there some way you can save face?’ ”

Indeed there was: “I have a great deal of sympathy with the argument that the needs of poor survivors in the United States should be carefully considered,” Neuborne wrote in an open letter to Dubbin’s clients. The first $100 million would be disbursed under the 75-21-4 formula, but he held out the possibility that future looted-assets money from the main $1.25 billion pile would be diverted to impoverished Holocaust victims in Miami and elsewhere in the States. “I will support thoughtful plans designed to assure that the needs of the American survivor community are addressed … with due regard for the fact that they have not received significant distributions up to this point.” Satisfied, the American survivors abandoned their appeal. Later Korman thanked them in a conference call. “You are performing a mitzvah, and I will not forget it.”

Yet subsequent distributions of $60 million and $45 million to the looted-assets class proceeded under the same formula: 75 percent to the former Soviet Union, 4 percent to the U.S. Feeling double-crossed, the American survivors filed a new appeal. And Neuborne, to their astonishment, opposed them. “It was a betrayal,” says Dubbin. “Instead of backing us, backing the plaintiffs, he backs the judge.”

Neuborne says Dubbin is trying to turn a face-saving gesture—the letter—into a promise. “We sat in that room, the judge and I, and we told Dubbin, ‘This is not binding … You understand that, don’t you?’ ” he says. Neuborne says the survivors misunderstand his role and that Dubbin misrepresents it. “I have tried to explain to them: ‘Look, of course I am going to represent you. But my representation is to make sure your views are heard by the special master and the judge. Once that happens, they will make a decision. And my job is to enforce that.’ ”

Neuborne, in his role as lead settlement attorney, inevitably became more CEO than crusader. The job had him develop a mechanism to file claims and explain it at survivor gatherings from Italy to California. There were negotiations in Switzerland for bank records and decisions on how to invest the money. Neuborne lobbied Congress, winning a tax exemption that saved tens of millions of dollars. Korman even asked Neuborne to review the bills of other lawyers seeking fees. “It was his work on every vacation, every trip. We go to Europe and he is faxing papers from the hotel in Paris,” his wife, Helen, says. “Nobody expected it to happen this way. It just happened.”

Last December, a week before Christmas, Neuborne sent Korman a letter. Nearly seven years had passed since he’d become lead settlement counsel. Neuborne had successfully defended every legal challenge to the settlement, including those filed by Dubbin on behalf of the American survivors. Hundreds of millions of dollars still had not been distributed, but systems to file, review, and pay claims for plundered bank deposits were in place. Neuborne thought it was time to get paid. In his letter, Neuborne reminded the judge that he had waived fees in the first phase of the case. He added, “Once it became clear that service as Lead Settlement Counsel would entail an enormous commitment of time and intellectual energy, you suggested, and I agreed, that hourly … compensation should be paid.” Neuborne declared that he had worked 8,178 hours since 1999, at $700 an hour. After applying a 25 percent discount, he staked out his bottom line: $4,088,500.

Neuborne’s fee petition surprised almost everyone. Wasn’t he working for free? they asked. For the American survivors, the $4 million fee was the final outrage. “In a class-action case, nobody is really thrilled that lawyers walk away with millions. But at least you know who your lawyer is; it’s clear that he’s working on your behalf,” says Thane Rosenbaum, a son of Holocaust survivors and a Fordham law professor who opposed the 75-21-4 formula. “This is twisted. The lawyer who fought you is sticking you with his bill.”

Even one of the dozen attorneys who worked on the case, Robert Swift, was “surprised, to put it mildly,” when Neuborne petitioned for payment. “I think it is unethical,” Swift told me. “When there is a fee arrangement, it must be disclosed to the client—in this case, the survivors. After the fact, we learned of an agreement between Burt Neuborne and the judge. What are the details? Why wasn’t it discussed?” Dubbin argues that it’s a conflict of interest: “Neuborne supported the judge in his rulings, then … asks the judge to approve his fees.”

Dubbin and Swift have gone to court to block payment. Neuborne responded with a gambit: He removed 1,600 disputed hours from his bill, but he also removed his discount, raising his fee by $671,500 in the process. The bill now comes to $4.76 million. Korman—who declined to speak with me because of the legal challenge—has recused himself. A federal magistrate, Justice James Orenstein, accepted written arguments from both sides over the summer and is expected to rule on the fee issue any day now.

“A fee must be disclosed. After the fact, we learned of an agreement between Burt Neuborne and the Judge. I think it’s unethical.”

In court papers, Neuborne argues that even though Korman never entered an order declaring that Neuborne’s pro bono status changed when he became lead settlement counsel, his bill should not have been a surprise. The issue of fees came up in a January 2001 court hearing and in a 2002 law-journal article Neuborne wrote, he says. A transcript of the hearing shows only that Korman was willing to award Neuborne fees for settlement work, not that Neuborne definitely was going to seek them. In his article, for the Washington University Law Quarterly, Neuborne addressed the issue in a one-sentence footnote: “Hourly payments for post-settlement work needed to administer the fund will be sought,” he wrote. Six lawyers who worked with Neuborne have submitted sworn statements saying they assumed that he would be seeking fees for his work on the settlement. Yet as recently as September 26, 2005, Neuborne made no distinction between the first, pro bono phase of the case, and this second, fee-for-service settlement phase, telling a federal judge in Miami, “I am the lead settlement lawyer in the Swiss case in which I served without fee now for almost seven years.” In person, Neuborne argues that the September 26 statement was just good lawyering, an attempt to short-circuit an avenue of appeal by making clear he had no financial stake in the settlement’s approval.

This summer, as the magistrate entertained arguments in the case, the Times weighed in with an editorial. It praised Neuborne’s role and said, “No one should be expected to do arduous, complicated legal work without pay.” But the editorial jumped on Neuborne’s request for $700 an hour. “The dollar amounts are troubling … Top corporate lawyers charge that much, or more. But Holocaust victims are not Exxon Mobil. It is an unseemly rate to be asking.” The Wall Street Journal published Neuborne’s rebuttal online: “During the Middle Ages the Catholic Church insisted that Jewish merchants charge a ‘just price’ instead of market value,” Neuborne wrote. “The Times has gone into the same business.”

The exchange encapsulates the eternal philosophical divide between idealists, who believe the Holocaust is not something anyone should be profiting from, and the market-based realists, who argue that justice has a price and it ought to be paid. Yet the extraordinary rhetoric and bitterness comes from someplace else: What seems like just a fight over the bill is, at a deeper level, a rift between the rank and file and the leaders representing them.

Rechter and other grassroots survivor leaders have long believed that the Jewish Establishment spends too much on Holocaust commemoration and too little on the needs of those who actually survived Hitler. They see Korman’s rulings—backed by Neuborne—as an expression of the organized community’s will over theirs and the ADL’s decision to give Neuborne its American Heritage Award, which is designed to recognize a fighter for American values, as a rebuke. “Institutions tend to have a very different pulse and mind-set than the rank and file. They are led by professionals … with law degrees and M.B.A.’s … who have a sense of administrative purpose and a feeling of ‘we know what’s best,’ ” says Rosenbaum. “It’s an appealing idea to force nations and banks to be accountable. But they forgot to listen here to the people who have the greatest moral authority, the survivors themselves.”