Seeking roommate for one-bedroom in Washington Heights. It’s a bit small for two but I have to catch up on some bills. Two friendly cats, but we keep clean because I’m a little allergic myself. A little more than half of the $950 rent gets you the privacy of the bedroom.

It was August 2003. I’d only recently found work, nearly a year after losing my job organizing school tours at an art museum, and my fiancée had just moved out of our apartment. It was a small, sunny place on the fourth floor of an old building, high enough on a hill that you could even see a little of New Jersey from the right angle.

We’d moved up there when she landed a medical residency at Columbia University Medical Center, but we’d split six months before the wedding. Without a job, I’d run up a ton of debt, and I urgently needed extra income to make rent, so I figured I’d lease out my bedroom and crash in the living room. I tried to pretend it was darkly funny, but really it just felt pathetic.

I got a flood of responses. A panicking female college student from the Midwest offered three months’ rent sight unseen, but she couldn’t meet me in person. An asshole with the e-mail handle of “elitist1” got impatient when I didn’t answer his questions fast enough. I fell for a blue-eyed, tongue-pierced vegan the moment I opened the door to her, but she wasn’t interested in the room, or me.

John “Don” Williams was enthusiastic about the apartment, at least. A middle-aged ghostwriter from California who’d lived all over, he turned up at my door in cargo pants and long sleeves despite the summer heat and talked with a slight southern drawl. He was punctual, which I liked. And he greeted my two cats warmly, which I also liked. “I’ve looked at a lot of apartments, and this is definitely the best arrangement I’ve seen,” he said. I was flattered, though he must have seen some real squalor. We played with the cats and chatted about pets. The two of us—a ghostwriter and an aspiring art critic—could compare notes on the writing life, we agreed. He moved in on August 21.

At first Don struck me as the perfect roommate. He was uncommonly neat and clean. To keep cat hair from coming into his room, he rolled up a towel and push-pinned it to the bottom of the door. He was often out, and when home, he stayed in his room without a peep for hours on end. Sometimes he would emerge from his room when I had imagined myself alone in the apartment and had been blasting music, talking on the phone, or listening to public radio while cooking dinner. He hardly ever had guests and was frequently gone for days at a time. I wasn’t thrilled with his unannounced comings and goings, but I let it go.

If anything, Don seemed boring, either putting his head down or making dull small talk as he passed through the living room. When he did speak, it was mainly to praise the beautiful women of New York. He had female guests a couple of times and alluded to several girlfriends. Despite a ring on his finger, he wasn’t married, and in fact, “the ring doesn’t seem to discourage women who are interested,” he said. I hadn’t dated in a while, I mentioned, but there were some situations I hoped might develop into something. “But it’s like film,” he advised. “It isn’t going to develop unless you bring it into the store to get developed.”

Four months into Don’s stay, with cash coming in on time each month, all was going smoothly enough, until the morning of December 13, when I got home after a long night out to find his room in total chaos. It had been ransacked. His clothes, toiletries, and magazines were strewn about the bed and floors. The closet door hung from one hinge off a busted frame. His locked red Swiss Army luggage lay slashed open on the floor, the cats sleeping happily among the jumbled contents. My stuff was untouched, but I was horrified.

I called 911, but the cops were useless. “Talk to your roommate about it when you see him,” they said.

Who knew when that might be? At this point, I hadn’t seen Don for well over a month. In mid-November, I’d e-mailed to ask whether he’d be back anytime soon. Had he taken the business trip to London that he’d mentioned? No, he replied. His younger sister had been in a car accident, and he was in Seattle visiting her. I hadn’t heard from him since. I e-mailed him repeatedly and got no answer.

I started to wonder about my lodger and what he might be hiding in his room. The break-in seemed too calculated and selective to be the work of a common thief, who might have simply stolen Don’s luggage or my computer. Even the cash I’d stowed in my sock drawer was untouched. My fantasies turned paranoid. Was Don a spy—or an Al Qaeda operative who’d turned my apartment into his base? Had the injured-sister story been a ploy to gain my sympathy? Or maybe the accident was real but had been caused by some other agent to distract Don long enough to retrieve something from his suitcases.

Unable to reach Don and thoroughly spooked, I changed the locks, packed his few things into a closet, and moved back into the bedroom, convinced he’d never return. He did. On Christmas Eve, he called when I was in the middle of tree-trimming at my parents’ home in New Jersey. He told me that his ailing sister had died and he was back in New York but couldn’t get into the apartment. At first I was petrified just to hear his voice, but as we spoke, I started to relax. Maybe I was insane and he was a normal guy—a possibility I’d consider over and over in the ensuing months. I told him about the break-in and said I’d meet him at the apartment at three the following afternoon.

I got there two hours early. Mortified at having assumed he skipped town when he’d actually had a family tragedy, I wanted to make it seem as though I had never moved back in. Back out of the closet came his luggage, and I scattered things around to make it look convincingly ransacked. Back on the windowsill went the action figures he had kept there. His plastic storage containers, just about his only furniture, went back against the wall where I’d found them. I reset the clock. I held my breath.

The doorbell rang at three o’clock, and there he was. He seemed tired and sad, as you might expect, and at the same time he seemed obsessed with trying to solve the crime. He searched through the room, sat among the wreckage looking closely at his scattered belongings, and even joked about the perpetrator’s clumsy closet break-in. Strangely, despite the damage, little had been stolen—old cell phones, a little cash, a printer, and some marijuana, according to Don. (The drugs surprised me. I’d only seen him drink a beer once, and he’d said one was his limit.)

I imagined the invasion as retaliation for his womanizing. One of Don’s lady visitors had an on-again-off-again ex-con boyfriend—was he the culprit? “It doesn’t make sense,” Don said. “That guy, I’ve seen him around, and if he did this, he would have made it worth his while.”

Don advanced his own theory: “Three people had the keys,” he said. “I didn’t do it, my sixth sense tells me you weren’t involved, and that leaves one person.” He suspected our eccentric next-door neighbor, Lev, a deeply indebted Lithuanian jazz pianist and self-published science-fiction novelist who fed the cats whenever I went away. “You know, he grew up in the Soviet Union,” Don said, “so you don’t know who he might have been involved with.” I just listened. It was ridiculous, but his explanation did have a certain Occam’s-razor appeal.

Don proposed that we mount surveillance Webcams in the apartment (I refused) and called in the help of his family. He brought over a woman he called his sister and had me relate the story of finding the crime scene. (“I’m sorry for your loss,” I told her. “It’s been a hard time,” she replied.) He also told me he’d sent some items to his brother-in-law in D.C., “a Fed,” he said, “so if there are any fingerprints on them, we’ll find out.”

It occurred to me I’d touched all his stuff when I moved back into the bedroom. What if he found out? To clear my conscience, I confessed. “You handled pretty much everything in there,” he said, as if asking for confirmation of something he already knew. “I found your prints, too.”

“Strong work,” I said, shocked but trying to play it cool. “How did you get them in the first place?”

“Oh, well, you know, you could always just take an empty out of the recycling bin or something.”

Don’s familiarity with law-enforcement techniques might have alarmed me, but I was too embarrassed about my stunt to think clearly—and his anger over the incident only fueled my guilt. When I asked him for compensation after he inadvertently damaged an artwork of mine, Don retorted that it should be balanced against the losses he’d sustained in the break-in, which, as he saw it, happened on my watch. “And when you told me about it, you were just, like, ‘Hey, here’s what happened, sorry.’ My reaction would have been, ‘What can I do?’ Because if I see you have a problem, I’m going to try to help you. That’s just the way I was raised.”

Stung by the insult, I told him he needed to move out. I didn’t understand why he’d want to stay, I said hotly, “when this whole arrangement is obviously broken.” But he didn’t react, and in the end, I backed down. Maybe he was right. Perhaps I had been selfish and insensitive. Over my objections, he installed a lock on the bedroom door and left his radio playing WNYC around the clock to discourage intruders. I complained to friends. “He sounds crazy,” they said. When I griped to Don about the lock, he made me out to be the lunatic. “You said it wasn’t a good idea,” he argued. “You didn’t say to take it off.” Once again, I gave up. I needed the money.

In June 2004, Don was missing again, and he had been gone for weeks. E-mails I sent him began to bounce back, and his cell phone was not taking calls. June 21, rent day, came and went. I let two more weeks pass before changing the locks. I then broke into my own bedroom, turned off the radio, and, for the second time, angrily set about packing up the possessions he had left behind.

In his bed, I discovered a laptop and a bulging manila folder that seemed innocuous enough, though I couldn’t help but look inside. There, to my total shock, were scraps of torn-up preapproved credit-card offers I’d received in the mail and tossed in the trash. That wasn’t all. On a sheet of notebook paper, he’d scribbled the names, addresses, and phone numbers of my family members; my mother’s maiden name; the date my parents had married; and the name and address of a contractor I was working for, apparently copied from a pay stub. He even had the name and number of a woman I’d met at a party. Equally alarming were notes on my credit-card information, along with my sign-in names and passwords to various Websites.

In an instant, I felt like an idiot, a sucker, the Jersey boy I am. Why had I trusted this stranger? I burned with shame and anger as I pictured him listening for me to leave for work in the morning so he could methodically search my trash and boot up my computer. A ghostwriter? What a moron I’d been. I’d never seen him write a word. But who was he? I searched everything in the room. A letter from JetBlue addressed to a Brandall Platt confirmed a flight to Oakland, California, in November 2003, the time of one of his previous absences. There were photocopies of Social Security cards and California driver’s licenses of a Charles Brown and an Andre Holmes and others. From the photocopies, I couldn’t tell whether the pictures were of my roommate. I found nothing bearing the name “Don” had given me: John Williams.

His bike was gone, but a bunch of withered bananas suggested his absence was unplanned. Had Don been in an accident? A detective from the local precinct suggested I contact local hospitals. When that didn’t work, he said he’d start checking jails. I called my banks and credit-card companies. Thank God there were no unauthorized charges and no new cards in my name.

I searched the closet, where I spotted a classic composition book that looked like a diary. Seething over how he’d invaded my privacy, I tore it open, looking for revelations amid his cramped scribblings, rife with misspellings and sentence fragments. On one page, Don had mapped out a movie of his life story: “He learned to drive at eight, he could do anything with his hands, and throughout his life, he could become invisible … ” “Met with Spike Lee today,” read one entry. “He’s really interested in the story, and wants me to send him the articles.” His journal said he once met Danny Glover by chance in the street and tried to sell him his story as well. He had even cast the big-screen version of his life: He was to be portrayed by Denzel Washington. Laurence Fishburne would appear as his brother. Angela Bassett would take on the role of his wife, and, of course, Halle Berry (“the sexiest woman in the world”) would be his girlfriend.

The diary also contained transcriptions of text-message exchanges with real girlfriends—“u have hurt me 2 many times,” one wrote—and vague laments over his kids: “I don’t even know who I am anymore … all I know is I’m the father of three beautiful, innocent children… . My babies, my babies … your dada cries every day.” Apparently, he also had reason to fear the police: “I’m only now just starting to get over being afraid every time someone looks at me twice in the street … every time a cop looks at me … thinking they know.” Know what?

I was becoming frantic. Craving more answers, I turned to his laptop, handing it over to a systems-administrator friend to circumvent his password protection by installing a new operating system. The sign-in name added yet another entry to the growing list of pseudonyms: Dino Smith. There, among various pictures of Don and his family, flyers for a business venture offering tours of the Bay Area in a Hummer, and a poster offering his services as a “personnel assisitant,” was the following diary entry, dated April 27, 2003:

I’m @ location 4. It’s been how many days now? Lets count from the 14th-15-16-17-18-19-20-21-22-23-24-25-26-27> 13 days today, dam, two weeks tomorrow … how the hell do I prove I was not there? When I truly was not there? Who the hells going to believe me. I can’t even get up on the witness stand, When those fuckers are going to do everything they can not to lose this case … I won’t sit up in jail for who knows how long and I know I’ve been set up by those no good fucking cops that I know don’t like me.

My hands started to shake. Had I been harboring a fugitive? Don had struck me as creepy, but I wasn’t prepared for this. My heart raced as I wondered what crime the cops could possibly want him for. I thought about the break-in, his absences, the dead sister, the fingerprinting … but what did it all add up to? Was he a victim of circumstance—or a serial killer? Was I his next target? I became obsessed with getting answers. Then I searched the most obvious place of all: Google. I typed in the name “Dino Smith,” and a couple of clicks later, there it was. His mug shot, on the America’s Most Wanted Website. He was a suspect in the biggest jewel heist in San Francisco history. I gaped at the screen in disbelief, then ran in circles, howling obscenities: “Fuck fuck fucking shit fuck fucker! Holy FUCK!”

I burned with shame and anger as I pictured him listening for me to leave for work in the morning so he could methodically search my trash.

I scanned the Web for more clues, cringing at each revelation. According to the Los Angeles Times, one night in April 2003, Dino, his brother Devin “Troy” Smith, and accomplices allegedly broke into a vacant restaurant adjoining Lang Antique & Estate Jewelry, burrowed through the wall, disabled the motion detectors, and hid in the bathroom overnight. When the employees arrived in the morning, the thieves forced them to empty the safes at gunpoint, then tied them up. The robbers hauled away $6 million to $10 million worth of diamonds and other jewelry in garbage bags. Four months after the heist, “Don” the ghostwriter moved in with me.

He’d been eluding the cops for fourteen months when he was captured on June 4, just a few days after I had last seen him. The police finally caught up with him outside the A subway station at Howard Beach–JFK Airport, where they had followed a girlfriend who’d flown in from the West Coast to visit him.

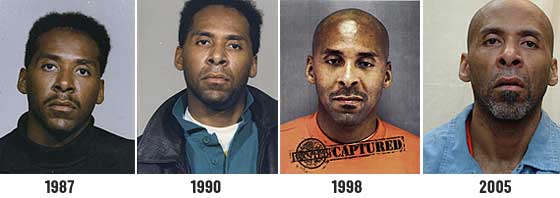

Dino and his brother had served time before. They were a notorious crime duo despised by cops and prosecutors for their slick arrogance and flamboyance. Known for his acrobatic robbery style, Dino reportedly escaped the police by using a handcuff key he’d hidden in the seam of his underwear. Between them, Dino and Troy had generated 20,000 pages’ worth of court documents, according to the L.A. Times.

In 1990, the brothers were arrested, and later convicted, for a foiled plot to kidnap and rob Lawrence Lin, also known as Dr. Winkie, the eccentric owner of the San Francisco nightclub DV8. (Wearing body armor and carrying semi-automatic rifles at the time of their arrest, the two improbably told cops they were on the way to protect Lin.) They were also convicted for a 1989 robbery in which they stole $400,000 worth of jewelry from the home of Victoria Magana, the widow of a Nicaraguan drug lord. This time, they told police she staged the theft herself to avoid payment on a $500,000 drug debt.

All told, Dino had 47 years to serve, and Troy 42. But they were sprung after less than a decade when both convictions were overturned, one because of attorney misconduct, the other thanks to police misconduct.

After their 1998 release, the brothers tried—and failed—to go straight. A brief stint as seamen for merchant ships at the Port of Oakland ended badly when the Coast Guard realized they’d lied about their criminal past on the applications, the Times reported. Troy fell deep into debt, and his marriage was falling apart. His wife claimed he had punched her in the face and had allegedly threatened that if she tried to leave, “I’ll make what O.J. did to Nicole look like a paper cut,” according to the paper.

What, then, might Troy have in mind for me? After all, he was still at large. Could Dino have given him my personal information? Could Troy be living as Brian Boucher at this very moment? I was so scared I called 911, convinced that he was on his way to find me. The cops looked around the apartment, twirling their batons as I tried to explain. “If you see the brother, call the police,” they said, and left.

I had better luck with the San Francisco police the following day. “We’ve really been hoping for a phone call like this,” said Dan Gardner, a robbery inspector for the SFPD. One evening just before the Republican National Convention, four men arrived at my apartment: the towering Gardner and his partner, along with two New York detectives. “So where’d ya find da jewels?” one of them cracked.

They donned rubber gloves and went to work, tearing outlets and switch plates from the wall, fondling the futon. One mentioned a Manhattan Mini Storage locker of Dino’s containing power tools and a concrete saw. I asked if they thought I’d hear from Dino again. “Look,” Gardner told me, “I don’t want to scare you, but they did catch him trying to escape from Rikers Island once already while he’s been in custody.”

In May 2005, I received a call from Jerry Coleman, a San Francisco assistant district attorney who asked me to come testify in the trial. Weeks later, I sat by myself in a San Francisco courtroom. The sole observer was a woman I’d seen in pictures from Dino’s computer, and it struck me that she and Dino had the same features. She had to be his mother.

A door opened and in walked Dino, looking sharp in tan pants and a black polo. No orange jumpsuit, no cuffs. The room fell silent. I hadn’t seen him in almost a year, and I couldn’t take my eyes off him. He sat and arranged his files, then turned to me and nodded hello with a nervous look of forced ease. “Hey, roomie. How funny seeing you here,” he seemed to say.

As they swore me in, I was afraid the microphone on the witness stand would pick up the sound of my heart pounding.

“Sir, in the events you’ve described, would you say you were acting as an agent of the police?” Dino’s lawyer asked.

Huh? I leaned into the microphone. “No, sir.” Maybe this wouldn’t be so hard.

Dino frequently shook his head, seemingly disgusted at the state’s flimsy case against him, and furiously took notes as I enumerated the identifying information he had collected on me.

The defense attorney tried to undermine the legitimacy of the computer evidence, on the basis that I’d left it with a friend to work on overnight. “So you don’t know what your friend did, by your own personal knowledge?”

“I guess that’s true.”

“No further questions, your honor.”

On June 3, 2005, based in part on evidence found on the computer he left behind, the jury convicted Dino Loren Smith, 55, on eight of eleven counts of robbery, false imprisonment, burglary, and conspiracy. On November 10, he was sentenced to 23 years in prison. He is now under processing at San Quentin, while authorities decide where to send him.

I still haven’t figured out who ransacked Dino’s room that time. Was it a would-be accomplice who’d been cut out of the jewelry-store job? Somebody who’d heard Dino bragging in the street? Was it Dino himself, trying to see how I’d react? Who knows? Nothing was what it seemed with my ex-roommate—the dead sister in Seattle never existed; the one he brought to the apartment was actually his wife.

An even bigger mystery concerns Troy, who’s still on the lam despite the FBI’s $50,000 reward. Every so often, I see a guy in the street who resembles his mug shot and I’m spooked into thinking it’s him. I tell myself I’m just being crazy, but then I’ve said that before.

I’ve since moved out of the place where I lived with Dino, into an upper-Manhattan apartment that I share with a financial planner, a dance teacher, and their 5-year-old son. I found them on Craigslist.