On Saturdays, when Alan’s father works a twelve-hour shift as a cook at a nearby restaurant, his best friend, Daniel, comes over to play. If it’s warm they run about, and if it’s cold they sprawl out on the mattress in Alan’s bedroom, which he shares with his parents and younger sister, and play video games. It is cold right now—two homeless men will be found frozen to death tomorrow in Brooklyn—so they are inside, and Alan’s 9-year-old face, normally gentle and wrinkle-free, is stuck in a grimace. He’s losing the fight.

Alan and Daniel’s favorite Sony PlayStation game is WWE Smackdown! vs. Raw 2006. Professional wrestling. Alan has chosen to be Rey Mysterio, a Latino wrestler who wears a hood like the Lucha Libre fighters of Mexico, and he’s getting pummeled by the much larger Stone Cold Steve Austin. On the television screen, Rey Mysterio attempts a kick, but Stone Cold catches and holds his leg. It looks like it might be all over. “He’s okay, he’s okay,” Alan insists between clenched teeth, pressing an assortment of buttons. Mysterio pivots and jumps, landing his free foot on Stone Cold’s face. “Mysterio is my favorite,” says Alan, as Stone Cold falls to the mat. “That move always works.”

Alan may have won this round, but Daniel is the undisputed king of PlayStation. (“Daniel has had a PlayStation for, like, forever—I only got mine last Christmas!” he explains.) So Alan looks to him for combat hints and other useful information.

“Was Mysterio born in Mexico?” Alan asks Daniel, as his character comes crashing down on the face of Stone Cold, elbow first.

“No, he’s from California. But his family’s from Mexico.”

“Oh,” Alan says, disappointed. “What about Eddie Guerrero?”

“Nah, he’s from Texas. It’s only his family that’s from Mexico.”

“I wonder if any of them were born in Mexico,” he says quietly, more to himself than to Daniel, “or if they all get to be born here.”

Alan pauses the video game, and his facial muscles finally relax. “I wanted to be born here,” he continues. “Because if you get your teeth all messed up and you’re born here, you get them fixed for free. But if you’re an immigrant, you have to pay. And I could go anywhere I want, ’cause I’d have a passport.” Daniel, who was born here but whose parents are from Mexico, nods in agreement without taking his eyes off the television.

Alan stretches his arms above his head and picks up the video-game controller. He directs Mysterio onto the top rope of the ring, where he lunges into the air, coming down with a violent crash but missing the opponent by several feet. “Oops,” he says, smiling. “I hate myself when I do that.”

Unlike his idol Rey Mysterio, Alan was born in Mexico. His hometown, Acatlán de Osorio, is in the southern region known as the Mixteca, which encompasses parts of Puebla, Oaxaca, and Guerrero. It is estimated that two-thirds of Mexicans living in New York originate from its remote farming towns, some of the driest and least arable areas of the country. Alan’s parents, Margarita and Rafael, weren’t poor by local standards—they helped run the family bakery—but in the nineties, several new panaderías sprouted up in Acatlán, and business slowed. In 1998, Rafael decided to follow the path blazed by his older sister, Elizabeth, who had moved to Brooklyn with her husband six years earlier.

“It was what a lot of people were doing,” says Rafael.

“He was just going to work in Brooklyn for a little while and then come home,” says Margarita, nodding. She was just 20 years old at the time, a striking girl with black hair she kept tied in a ponytail. As she watched her husband climb aboard a midnight bus from the central plaza of Acatlán, she carried Alan on her hip. He was just 16 months old.

A little while stretched into a long while, and in April 2000, after two years of washing dishes, cooking omelettes, and earning dollars rather than pesos, Rafael suggested that, rather than him coming home, his wife and child should make the 2,500-mile journey north.

Margarita knew the trip would be arduous, especially for a 3-year-old. “I didn’t want him to have to cross illegally and maybe get hurt,” she explains. To minimize the risk, she arranged for a coyote, or human smuggler, to obtain a birth certificate for Alan. This was the plan: Margarita would ride across the All-American Canal near Mexicali on an inflatable raft with five other migrants, and Alan would pass through the immigration checkpoint in Tijuana, about 50 miles away, with a smuggler who had the proper papers. The whole thing would cost $2,000, and Rafael would wire the coyote the money. The catch was that Alan had to remember to lie: If asked, he would need to say that his name was José, to match the birth certificate, and that the smuggler, Arturo, was his father.

When they got to the border, Alan was asleep, and Margarita dropped him off at a safe house with Arturo. “I’m glad he was sleeping when I left him, because he would have been worried to see me,” she remembers. “I was crying and shaking a lot, and I couldn’t stop.” Arturo promised her that Alan would be safe and that she would see him again very soon, but Margarita couldn’t escape the feeling that something terrible might happen to her son.

Margarita’s crossing took longer than advertised. Her group spent two days waiting on the border because one of their guides got word that Border Patrol agents were swarming the area after a recent drug bust. Finally, on the third evening, the group navigated the canal and then waded through fields of alfalfa, with standing water up to their knees. Dodging the headlights of Border Patrol trucks, they continued walking until they came to a waiting van, which spirited them into the California desert, where another van was supposed to pick them up. They waited for another three days in the desert, sleeping outside in garbage bags. The guide had brought along enough chicken and water to sustain them, but Margarita was so worried about Alan that she hardly ate. Eventually, the second van arrived and took Margarita to the house in Santa Ana where Alan was staying with the smuggler’s family. It was there that Margarita learned how well Alan had taken to his false identity.

“He said that his name now was José,” she remembers. “And I told him, ‘No, you are Alan now,’ but he still kept saying he was José.” Days later, as they were preparing to land in Newark, Margarita asked Alan if he was excited to see his papá, and Alan told her matter-of-factly that he wasn’t going to see his father, because his father was named Arturo and he was still in California. When they landed, Rafael was waiting to greet them at the airport. He hugged his son, marveling at how much he had grown. Then Alan announced again that he wasn’t really named Alan and that Rafael wasn’t really his father.

“Imagine your own son says that he has a different father!” says Rafael. Alan’s parents still aren’t sure whether he was joking; after all, he hadn’t seen his real father in two years. But after a week his memory of Arturo faded and he began to acclimate to life in America. It was difficult at first. Margarita summed up her impression of her new neighborhood in one word: feo. Ugly. Alan didn’t much like the cramped, urban setting either; there wasn’t as much room to play. But it wasn’t long before he was speaking English without an accent, eating Happy Meals at McDonald’s, and watching Pokémon on TV.

Alan’s home in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Sunset Park is small and crowded. It’s a basement apartment, with two small bedrooms that seem large compared with the common room and kitchen. The living space has so many odds and ends stacked against the walls that it looks like one long hallway. In all, eight people live here. There are Alan and his 4-year-old sister, America, and their parents, plus Alan’s aunt Elizabeth and her husband, Guadalupe, and their two children, Adriana, who is 13, and Angel, just 6 months old. Each four-person family shares a single room. All of the parents are undocumented immigrants, as is Alan. Adriana, Angel, and America, born after their parents moved to New York, are U.S. citizens.

“When they told me I needed to hide in a bag, I thought I wouldn’t live,” says Alan. “I was real, real nervous.”

The important institutions in Alan’s life are all within walking distance. His school, which is two-thirds Latino, is half a block from his apartment; his church is three blocks away; and there’s a Salvation Army nearby, which has a basketball court where he and Daniel play with the kids in the neighborhood.

He gets along well in school and especially enjoys math, but when the topic turns to reading, he furrows his brow like a person three times his age. “Language is my worst subject,” he explains. “Last year, I was real worried ’cause I didn’t think I’d pass the reading test, but I got a three, which is pretty good. I think I might not pass this year, though.”

Only once has the school called Alan’s parents because of misbehavior. According to Alan, a group of Puerto Rican students regularly teased and sometimes hit him. “One day, I got hit in the back during class, and so I hit the kid.” The teacher witnessed the second infraction—Alan’s—and called his father. Rafael was angry, but not with Alan. “Why did they only have a meeting with me and not the parents of the other kid that hit Alan?” he asks. Rafael suspected that the teacher was biased against Mexicans. He made Alan promise to never hit anyone again and to tell him when he was having problems, so that he could speak directly to the teacher.

Alan insists that he was never afraid of the Puerto Ricans, even when they ganged up on him, even when it was five against one. He is afraid, though, of Freddy from A Nightmare on Elm Street, Jason from Friday the 13th, and Chucky from Child’s Play. “Chucky is real, real mean,” he says. He vows to never again watch a Chucky movie. “Why would I want to? It’s not fun.”

He is also afraid of the police. “I used to have lots of nightmares. Like, there were lots of cops that were chasing me, and they were going to catch me and never let me go and keep me forever.” He explains this fear quickly, wanting to leave it behind. In some ways, it is a universal childhood anxiety—being chased and caught—but in other ways, it is Alan’s very own, a product not of an overactive imagination but of life experience.

In February 2003, Rafael’s father, Catalino, suffered a massive heart attack and spent four days in the hospital in Acatlán. Word came to Brooklyn that it didn’t look like he had much time left, and Rafael and his sister Elizabeth began to plan a trip home. “He was sick,” is what Alan remembers, “and I wanted to go to visit.” Although his parents knew that 6-year-old Alan’s return trip to Brooklyn would be costly and complicated, they agreed to let him go: It could be his last chance to see his grandfather, who had been like a father to him in the early years of his life, after Rafael left for New York. In March, the family flew to Mexico, a trip for which they needed only their Mexican passports. Margarita, who had just started a new job folding clothing at a factory, decided to stay behind.

When they arrived at the house, Catalino was sitting in a chair in the living room. Alan ran up to his grandfather, hugged him, and began sobbing. Soon Catalino was crying as well. “My father was the kind of person who almost never showed any emotion,” Elizabeth says of the event. “He never cries about anything, but he was crying when he saw Alan. They were very close because Catalino practically raised him; it was where he grew up. Alan always wanted to be with hisabuelo. Even after he came to Brooklyn, he would talk about him every day.”

Rafael had only a week off from the restaurant where he worked, so when his time was up, he left America and Alan with Elizabeth and made his way back to the U.S., flying to the town of Mexicali and then hiking for ten hours across the border into California. In April, Rafael’s cousin Salomon, who is a legal U.S. resident, flew from Brooklyn to Mexico to pick up America. Alan was furious that he couldn’t fly home like his sister. And the explanations he received weren’t convincing.

“I yelled at my tía about why my mom didn’t have me in America if it’s so important, and she told me that it wasn’t possible.” The logic escaped Alan: He had been well behaved on the airplane trip to Mexico, after all—much quieter than his sister. So when it came time to say good-bye to America and Salomon at the airport, Alan couldn’t stop crying tears of frustration and anger. “I guess they thought I needed a passport,” he says now. “Or maybe that I was a murderer?”

Either way, it was time for him to make the second illegal journey of his short life. The following week, he and his aunt Elizabeth said good-bye to his grandparents and got on a bus headed for the Mexico-Texas border. When they got to Nuevo Laredo, Elizabeth called her parents to check in, but no one answered. They were already at the hospital: Catalino had suffered another heart attack. Holed up at a border motel, Elizabeth kept reminding Alan that if they got captured by Border Patrol agents, he needed to remember to say he was her son, so that they wouldn’t be separated.

After two days of waiting, the coyote told them at dusk that they would be leaving the next day. Sitting in his bedroom with Daniel as a Spanish-language talk show plays in the background, Alan tells the story. Each of the seven people in their group was given a life preserver, and Elizabeth kept a firm grip on Alan as the two waded into the Rio Grande. “It was fun because I was in the water, like all over,” Alan says. “The water was dark green, really dark. I think it was fun ’cause it was my first time ever in a river. Even my arms were wet. And there were two men that helped pull us onto the other side.”

He pauses.

“But it was even more scary because the cops—they wanted to arrest us. There were planes flying around. One of the cops was bald, and one had real long hair. When they caught us after the river, they drove up and we all stopped. They asked me if I wanted candy. I said yes, so they gave me a Snickers. It was king size. They were both nice.”

As Alan speaks, Daniel listens intently: He has never been in a river, either, and he doesn’t know any other grade-school kids who have been taken into custody by the Border Patrol. Alan takes a deep breath and turns his attention to his friend. “It’s true. I was really arrested. For real.”

After an internment of several hours, Alan and Elizabeth were dropped off on the Mexican side of the border, and they returned to the motel. Twenty-four hours after their first attempt, they retraced their steps: floating across the river, sprinting up the other side of the bank, then dropping to their stomachs and waiting. “One of the men was using a walkie-talkie to try and trick the cops,” Alan says. “Then we went to a place where a van got us and then to a small house that already had people in it. That’s when my tía told me about what I had to do.”

Elizabeth had had two options as to how they would cross the border. The cheapest, at $1,800, was also the most dangerous: marching through the night, into Arizona. Hundreds of migrants perish each year in the unforgiving terrain of the Sonoran Desert. Treks can last many days, and temperatures regularly reach 110 degrees. Smugglers are prone to ditch their charges at the first sign of trouble, leaving them to wander aimlessly without enough water.

Elizabeth preferred the river, especially with a child. The smuggler charged $2,500 a head to move people across the Rio Grande, bypassing the border checkpoints, where security is the tightest. “The coyote told us that they would look closely at us and maybe take our fingerprints at the border,” Elizabeth says. But just making it to the van waiting on the other side of the river wouldn’t mean they were home free. There are other checkpoints along the road in Texas. “After you get past the first stop, the other checkpoints aren’t so hard,” explains Elizabeth. “They usually don’t even make you get out of the car, so it’s hard for them to really see your face.”

Once in the van, the coyote handed out stolen identification cards for the migrants, trying to best match the faces on the I.D.’s with the soaking Mexicans. But the man in charge had already told Elizabeth that the smugglers didn’t have any documents for a child. What they did have was a large black duffel bag.

“When they told me I needed to hide in a bag, I thought I wouldn’t live,” Alan says in a hushed voice, his eyes widening. “Like, I couldn’t breathe good, and I was real, real nervous.” He leaves the bedroom and returns with a fist-size toy car for demonstration purposes. “See, my tía was sitting in the back, here, and I was down by her feet. In the bag. We were driving, and the cops were coming after us. And then she said, ‘Be quiet.’ ”

As they approached the last immigration checkpoint, Elizabeth unzipped the bag half an inch so that her nephew could get a last breath of fresh air. She remembers every painstaking moment. “I told him, ‘Don’t move until I say it’s okay.’ Then I zipped it back up and put my hand on top of his head, like he was just my things.” The van slowed to a stop, and a Border Patrol agent asked for Elizabeth’s identification. With trembling hands she turned the green card over. What if he was suspicious and decided to search the van? The agent looked at the card briefly and handed it back. The van continued on. A number of miles past the checkpoint, a family friend from Brooklyn was waiting with his car, and Alan and Elizabeth piled in. “When they let me out of the bag, I was smiling and laughing,” Alan recalls. “It was so hot in there!”

But his wave of relief didn’t last long. “Then they told me we were in Texas. Can I tell you what I was thinking about? I was so nervous because I was thinking about the chain-saw massacre.” Daniel nods. He’s heard of the movie, too.

On the afternoon of July 28, 2003, Margarita left her job at the Brooklyn clothing factory and picked up Alan from summer school, where he was making up work he’d missed during his trip to visit his grandfather. Margarita wasn’t sure how to break the news—“My son is very sensitive, you know,” she says, sounding both concerned and proud—and so she remained silent as they walked home, holding hands.

But when Alan passed through the front door, he immediately knew something was wrong. Aunts and uncles and cousins filled the living room, and everyone was crying. Along one wall was a framed photo of Catalino next to bunches of flowers and burning candles. “Alan, something very sad has happened,” Margarita said, tears beginning to run down her face. “You’re not going to be able to see your grandfather anymore. He’s gone away to a better place.”

Alan went into the bedroom and closed the door, then turned on the television. “When I heard my abuelo died, I didn’t even cry,” Alan says. “Ummm … I guess I did cry, actually. One tear went down my face here.” He motions to his left cheek. His mother has told him about the lone tear, and it’s unclear whether he is remembering the tear or remembering the story.

“It was like he was in shock,” Margarita says, “like he wasn’t really ready to understand what had happened. He never wanted to talk about his abuelo after that. He acted like everything was completely normal.”

Six months later, Alan’s teacher called to say that he was falling behind and in danger of having to repeat the second grade. They arranged to have him speak to a school psychologist. In one of the first sessions, Alan told the counselor that he wanted to join Catalino, something that still causes his mother to shudder. But after a couple of months of therapy, he started to show signs of improvement. One day that spring, Alan told his mother that it was okay that his grandfather had died, “because even maybe though I can’t see him, he’s still here with me.” A few more sessions and the psychologist said that Alan was going to be fine.

For Alan, the mystery of death is mixed with his idea of Mexico, which remains a magical place in his memories. When he thinks of the home where he spent his first years, he remembers the heat, the bustling plaza, the bread that was always being baked. “The last time I went home, I was old enough to help my abuelo make the bread,” he says proudly. “I would add big buckets of water and lots of flour into the machine.” He grins. “The bread … the bread there is so tasty!”

And though he knows that his grandfather is dead, when Alan’s thoughts turn to Mexico—when he wonders what his cousins are up to, for example—he can’t help inserting Catalino into the scene. He can still see his grandfather rising early to bake bread, walking around the plaza with his straw hat shading his face, sitting in his favorite chair at the end of a long day.

On Wednesdays, the day their father has off from his job at the restaurant, Alan and America like to go to Burger King for an early dinner. When the workers don’t listen carefully to his order, Alan spends five minutes meticulously separating the lettuce, pickles, and tomatoes and placing them to the side, where they will eventually be tossed in the trash.

As they walk to the restaurant this afternoon, America is trying to decide which of two songs is her absolute favorite. “Me gusta mucho la ‘Gasolina,’ ” she says, and then sings a few lines from the tune that seems to be blasting from every stereo in New York. “But me gusta más el ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat’!”

After Alan’s two adventures crossing the border, Rafael and Margarita’s decision to name their only U.S.-born child America seems ripe with meaning, and it is. “América is my favorite,” Rafael explains, referring to the Mexican professional soccer team. “Lots of people like Cruz Azul, but I’ve always been a fan of América.”

It is a strange reality that Rafael and Margarita’s feisty 4-year-old daughter, who is barred from crossing the street without holding a guiding hand and cries loudly when faced with a doctor’s needle, will eventually have the power to legalize the status of her entire family, moving them out from the undocumented shadows, where deportation remains a constant possibility. If the emotionally charged debates in Congress fail to lead to an immigration-reform bill that allows a path to citizenship, Alan and his parents will have to wait until America turns 21 before she can petition for their permanent residency. That critical day will come in 2022, and by then, Alan will be in his late twenties.

“The cops caught us after the river and gave me a snickers. It was king size. They were nice.”

Rafael, however, doesn’t plan on staying in the U.S. indefinitely. Once he’s saved enough money, he hopes to return to Acatlán to farm the land of his father, fulfilling a promise he made to Catalino before he died. Margarita and the kids will stay in Brooklyn until Alan and America graduate from high school. After that, Rafael says, he isn’t sure whether his children will live in Mexico or the U.S. “It will be their decision to make,” he says.

“I’m going to live in Mexico,” Alan announces, taking a long slurp of Coke.

“Me too!” says America.

“But you won’t have all the things that you have here,” Rafael argues. “Like all your friends and movies and video games.”

Alan looks at his father, thinking for a moment. “I don’t care. I have cousins in Mexico.”

“Me too!” says America.

After lunch, the three walk back home and settle down in their bedroom to watch home movies from Acatlán. One of Alan’s favorites was shot when he was little, a year before he left Mexico for the first time. There is Alan riding on a cousin’s back, as if he were riding a bull. There he is dancing until he becomes dizzy and falls on his behind.

“See, you used to like to dance,” Rafael says to his son. “The song is one of his grandfather’s favorites. It was always on in the house. But now he says that he doesn’t like to dance.”

Alan giggles, embarrassed. “I only like to dance to rap,” he explains to his dad. “Like … I like to dance to 50 Cents.” He picks up his older cousin Adriana’s DVD Get Rich or Die Tryin’. “This is a good movie,” he says.

“Oh, I don’t like that!” America yells. “It’s too scary. Yo tengo una película de Shrek,” she says, then switches back to English. “And I have Madagascar and Cinderella … ”

“Ecchh,” says Alan, picking up one of his toy wrestling figures.

Watching the videos makes Alan think about going back to Mexico for another visit. “Yeah, if I go back there, then I have to cross again.” He puts the toy down. “But I don’t wanna go back, because I’m scared of the river now. Actually, I probably won’t ever go back. I really don’t want to have to get chased again.”

On the television screen, a dark-skinned man wearing a straw hat and a white short-sleeved shirt passes by, carrying a basket full of bread. “That’s my grandpa,” Alan says. “When I was there, we planted a seed to make a tree. Maybe it’s a tree now?” he asks himself. Still watching the screen, he nods. “Yeah, it has to be a tree now. When I go back, I’m gonna make sure to see it.”

A few moments pass. “Oh, wait. Then I’d have to cross!”

He’s momentarily stumped. “Wait. I know! I’ll just go back and stay. No one would ever try to catch me then!”

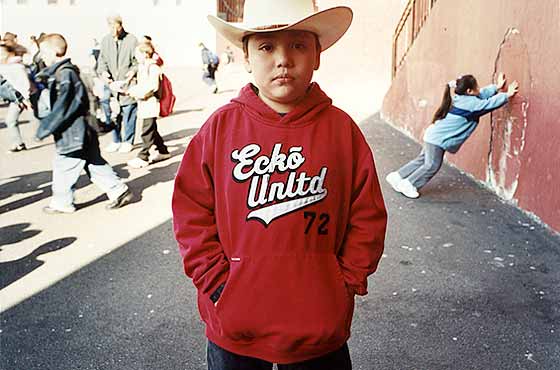

On the cloudy and humid morning of April 1, Alan is wearing a navy-blue shirt that reads YO SOY 100% MEXICANO. He trails behind Margarita, Elizabeth, and America as they join the thousands of people preparing to march across the Brooklyn Bridge to protest a new immigration bill that would turn undocumented immigration into a felony. He and Daniel are practicing chants. “I know a good one!” shouts Alan. “George Bush is unfair, he can kiss my butt!” Daniel nods his approval. “If the new law passes, then every immigrant has to go back to their country, even me!” Alan explains to his friend.

A helicopter hovers above the crowd, and Elizabeth turns back toward her nephew. “Be careful!” she shouts. “Immigration is watching us!” Alan looks concerned for a moment but breaks into a smile when he sees Elizabeth laughing.

“April fools!” Daniel says. “They’re not gonna mess with you here. But it’s not fair, man. Even though I’m not an immigrant, it’s still not fair. My parents are immigrants. Over there, it’s a lot of poorness, and the houses aren’t nice. People should be able to come.”

“My house in Mexico is real nice,” Alan responds.

“Well, but some people don’t have nice houses. That’s what I’m saying.”

A TV camera trains in on the boys, who raise their fists and begin another chant. “Queremos justicia! We want justice!” Once they pass the cameras, Daniel and Alan quiet down, pleased by the attention.

“We’re going to be famous!” Alan says.

“Do you know what channel they were from?” Daniel asks.

“No. Are you watching Wrestlemania tomorrow?”

“I can’t, ’cause I don’t have pay-per-view.”

“Me neither.” Alan looks down through the cracks in the bridge pathway. “Whoa! We’re really, really high up right now!”

“How are we gonna watch Wrestle-Mania?”

“I don’t know,” Alan says. “But we have to see it. Rey Mysterio is fighting.”