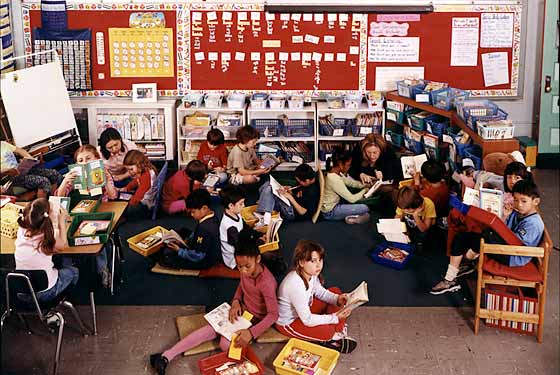

Every morning, about twenty minutes or so before lunch, the eighteen children in Lauren Kolbeck’s second-grade classroom at P.S. 29 in Cobble Hill are left to read quietly to themselves. Asking a bunch of 7-year-olds to do anything quietly for this long might seem about as sensible as asking them to ignore cupcakes. But these kids are managing. To keep them interested, Kolbeck has stocked the room with a few hundred books sorted into multicolored baskets and segregated by reading level; Beverly Cleary and Judy Blume share space with the Arthur and Amelia Bedelia franchises.

In a far corner of the room, a girl named Enami sits cross-legged on a moss-green rug, a floppy paperback in her hands. Her selection is from the Henry and Mudge series, about a boy and his dog. Tall and shy—she just turned 8—Enami says she picked this book because, well, she likes dogs. With Kolbeck peering over her shoulder, Enami opens the book and bobs her head, the bright blue beads in her cornrows jostling as she starts reading aloud.

“On a sun day … ”

It says sunny day in the book. But Enami’s a little tentative. She hasn’t read this one before.

“A man with a collar … ”

The teacher has a suggestion. “Sometimes we look at the picture and figure out if it makes sense.”

Enami eyes the drawing of a man walking a dog. She agrees collar doesn’t seem right. After some discussion, it’s decided that collie works better.

“A dog!” says Enami, satisfied.

She continues—and a page later she trips up on the word disappeared. She takes her best guess: “Stepped.”

“Let’s see if that makes sense,” says Kolbeck.

Again, Enami checks the drawing: a man at the end of a street, turning a corner. Her eyes flash—“Disappeared!” And on she goes.

If throwing Enami into the deep end of the pool like this seems a little intense, that’s pretty much the point. What’s unusual about this lesson—and to its critics, flat wrong about it—is what’s not happening. Enami and her seventeen classmates are not sitting in a row, repeating letter and pronunciation drills. They almost never are. There’s not a textbook in sight, or, for that matter, in the whole school. Instead, they’re learning by immersion, reading books of their own choosing, and when they mess up, which is often, they’re told to keep going.

Kolbeck and the other teachers at P.S. 29 are following the dictates of what’s called Balanced Literacy, an equal parts celebrated and maligned teaching technique ordered into the city schools three years ago by Michael Bloomberg and his schools chancellor, Joel Klein. Balanced Literacy is more of a catchall concept than an actual curriculum, interpreted slightly differently in every school system that uses it, but it is invariably rooted in an education philosophy known as whole language. Unlike traditional so-called phonics-based programs, in which kids repeat and memorize basic spelling and pronunciation rules before tackling an actual book, whole language operates on the presumption that breaking down words distracts kids, even discourages them, from growing up to become devoted readers. Instead, students in a Balanced Literacy program get their pick of books almost right away—real books, not Dick and Jane readers, with narratives that are meant to speak to what kids relate to, whether it’s dogs or baseball or friendship or baby sisters. Over time, the theory goes, kids learn the technical aspects of reading—like contractions, or tricky letter combinations painlessly—almost by osmosis. The joy of reading is meant to be the spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine of spelling and grammar go down.

Smitten with this approach, Klein, who mandated Balanced Literacy at nearly all of the city’s 743 elementary schools in 2003, after just a few months on the job, delights in visiting classrooms like Enami’s that are now stocked with “real” books and not textbooks. It’s long been a centerpiece of his speeches that the only reason he did well in school, and went on to become a successful federal prosecutor, was because a teacher handed him a book about baseball, a book he actually enjoyed and read.

Hundreds of thousands of New York children are now learning to read this way, and it’s Klein’s belief that Balanced Literacy is the main reason the city’s all-important fourth-grade literacy scores have gone up 7 percentage points since 2002, according to the latest national survey.

The catch is that in the past five years, research has emerged suggesting that phonics, not whole language, is the superior teaching method. Phonics advocates point to the new research as evidence that the Klein reading revolution is badly misguided. What’s needed, they say, is a phonics counterrevolution.

So goes the crossfire in the Reading Wars.

The reading wars, of course, aren’t only about reading. Yes, reading skills matter tremendously to New York parents, whether they aim to get their children into Harvard or just to their age-appropriate reading level. But the Reading Wars are also about race and class. Everyone stands to gain from phonics, advocates say, but no one figures to benefit more than children from low-income families who—unlike, say, the kids at elite private schools, most of which use a whole-language approach—often can’t get extra tutoring in the basics. Parents of children with learning disabilities say their children benefit similarly from phonics.

There’s also a political component to the Reading Wars. To phonics advocates, whole language is rooted in the worst liberal traditions: It’s a freewheeling approach that lacks rigor and standards and could even, some say, be the first step down the slippery slope to abominations like Ebonics. And the entire New York City education culture, they say, is permeated by such soft thinking. Whole-language proponents, in turn, say phonics perpetuates authoritarian, patronizing “drill and kill” strategies that insult the art of teaching and turn kids into fifties-style robots, putting them off learning for life.

Where George W. Bush and many red states are phonics supporters, New York is dyed-in-the-wool whole-language country. Influential programs at Columbia and Bank Street College developed variations of the approach before it even had a name. Balanced Literacy, or at least the way it’s practiced in New York, is largely the brainchild of Lucy Calkins, founder of the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, who is looked upon nationally as a godmother of whole-language learning.

The issue in New York is that at the exact moment that Bloomberg and Klein made Balanced Literacy the cornerstone of the curriculum here, phonics scored several major victories in the Reading Wars. A National Institutes of Health–created commission of Ph.D.’s came down squarely on the side of phonics in a 2000 report, influencing the Bush administration to crack down—some say improperly, perhaps even scandalously—on non-phonics programs. And where hard science once had little to say about how various reading methods affected kids, a series of MRI studies done at Yale starting in the late nineties appeared to show that as many as one in every four children, regardless of class, race, or other demographic factors, needs direct instruction in basic skills before he can read. When kids with learning difficulties read with phonics, their brains light up on MRI scans like a Christmas tree. The conclusion, phonics advocates say, is clear: Kids need technical instruction in the basics before being immersed in the world of literature.

That argument doesn’t persuade Klein. He’s cultivating mindful, curious readers, he’s said, not vanilla word-decoders. “I’m quite convinced the curriculum we’re using, with inquiry-based learning, will serve our students throughout the city well over time,” he says. In particular, Klein likes that Balanced Literacy looks a lot like the reading approaches in successful school districts on the Upper West Side and the Upper East Side and in most of the city’s elite private schools. In a system where so many great schools coexist with so many horrible ones, Klein is convinced that the solution is not to adopt the practices of the worst schools but to export the best practices of the successful ones and end the educational apartheid.

To phonics advocates, this is like turning your back on the invention of the wheel or the secret of fire. Despite the modest improvements in city reading scores, they say, the reading crisis isn’t going away here: The city’s high-school-graduation rate is still only 54 percent. Phonics, supporters say, could be the closest thing New York gets to a vaccine that can stop kids’ reading difficulties before they start. Why, they demand to know, isn’t New York using it?

It’s safe to say that when Michael Bloomberg came to City Hall in 2002, one of the last things on his mind was the best way to teach kids how to read. Taking over the public schools, as he improbably persuaded the state to let him do in his first six months in office, was more about management changes to him than pedagogy. In the summer of 2002, he hired Klein, a fellow outsider, as his chancellor, and Klein recruited a career superintendent named Diana Lam as his deputy for instruction. It was Lam who brought in Balanced Literacy. Neither Klein nor Bloomberg knew much about the program at the time, except that Lam had used it in cities where test scores went up, like San Antonio, Texas, and Providence, Rhode Island. For a mayor who wanted his first term judged on what he did with the schools, this was a clear plus. In what would be one of their only moments of agreement, Randi Weingarten, the teachers-union chief, agreed at first with Klein’s plan and even went out of her way to praise his bravery. “If the system isn’t working and someone has an idea that could theoretically make things much better,” she said in an interview, “why not try it?”

It didn’t take long—just days, actually—for the phonics camp to open fire. When Lam and Klein unveiled their reading program in January 2003—Balanced Literacy, with a small supplemental program called Month by Month Phonics—seven reading researchers unconnected to the public schools wrote an open letter to the mayor and Klein, blasting Month by Month Phonics as a phonics program in name only. They called Month by Month “woefully inadequate,” lacking “a research base” and “the ingredients of a systematic phonics program” and putting “beginning readers at risk of failure in learning to read.” Others were still less kind: Sol Stern of the conservative Manhattan Institute and the education historian Diane Ravitch berated Balanced Literacy’s whole-language roots. “Many of the programs and methods now being crammed down the teachers’ throats have no record of success,” wrote Stern, “and are particularly ill suited for disadvantaged minority children. In fact, a cabal of progressive educators chose them for ideological reasons, in total disregard of what the scientific evidence says about the most effective teaching methods—particularly in the critically important area of early reading.”

Parents in the more politically connected parts of town didn’t need to be won over by Balanced Literacy, since more than 200 elementary schools already used it. But the ones who sent their kids to the other public schools were bewildered by a reading program that didn’t have a textbook. “I held four days of hearings on reading,” recalls Eva Moskowitz, then the City Council’s Education Committee chair. In the hearings, she says, the city was hammered for what some called its “loosey-goosey” approach to teaching basic skills.

Phonics could be the closest thing New York gets to a vaccine that can stop kids’ reading difficulties before they start. Why, advocates demand to know, isn’t New York using it?

Parents’ outrage was matched by that of teachers who had been asked to switch curricula in real time with just a few days of training and little day-to-day support. Instead, principals were handing them daily directives from the Tweed Courthouse to reconfigure their classrooms and lesson plans. The workload became staggering, and many teachers resisted, blasting Lam in the press for punishing teachers who didn’t rearrange their rows of desks into cozy clusters or lay “reading rugs” in the corners. To some, Balanced Literacy became a buzzword for a new, bizarre form of tyranny. What was supposed to have been a progressive, flexible technique to unleash a child’s inner reader had become something so claustrophobically scripted that critics predicted Klein would drive the most talented teachers out of the system.

The curriculum, in fact, became a lightning rod for the mayor’s entire overhaul of the schools. Every criticism of the reforms, it seemed, circled back to the reading program. When the mayor tangled with the teachers union over contract negotiations, Weingarten abandoned her early enthusiasm for Balanced Literacy and demanded it be abolished. When the mayor ended social promotion for third-graders in 2004, Ravitch insisted that Klein ditch the scientifically flimsy curriculum. And when Lam abruptly resigned from her job in disgrace—exposed for getting her husband a job in the school system and trying to cover it up—it surprised no one when Sol Stern and others argued that it was time to scrap the “unproven” curriculum Lam brought in.

Cognition experts like Harvard’s Steven Pinker have argued for some time that while learning to talk is an organic process you can generally learn on your own, like walking, reading is more like riding a bike or driving a car. Someone has to take you through the initial steps and get you over the unfamiliarity of the experience; then you have to spend time on your own perfecting the skills until it becomes second nature. The question at the heart of the Reading Wars is how much direct instruction do children really need.

The debate has raged, back and forth, across the country—phonics was out in California, then in again, and battled over in Texas and elsewhere—until finally, in the mid-nineties, NIH launched a project intended to settle the matter. In 1997, Congress asked NIH to create the National Reading Panel (a commission of academics) to consider the question. The panel took three years to review and scrutinize 1,000 recent academic studies of phonics-related reading programs, eliminating all but the most carefully constructed. In 2000, the panel released its “meta-analysis” and concluded that in order to learn to read, all children must master five separate skills: phonemic awareness (separating words into distinct sounds, like the c, a, and t in cat), phonics (learning the sounds letters and letter combinations make), fluency (the ability to read with speed and accuracy), vocabulary (learning new words), and comprehension (understanding what you’re reading). These basic skills were nothing new to most people who taught elementary-school English. What the NRP added to the debate was the notion that direct instruction of these skills was the only proven method for teaching reading.

As a direct result of the NRP, those directing federal educational policy held up phonics as a sort of magic bullet, even though the data, critics say, fell well short of supporting such a blanket conclusion. For example, while the full NRP report acknowledged that “phonics instruction failed to exert a significant impact on the reading performance of low-achieving readers in second through sixth grade” and “there were insufficient data to draw conclusions about the effects of phonics instruction with normally developing readers above first grade,” the more widely distributed NRP summary report endorsed phonics without qualification. “Phonics instruction,” it read, “produces significant benefits for students in K through sixth grade and for students having difficulty learning to read.”

The conspiratorially minded likened the NRP study to other Bush-era tactics like payola for columnists or doctoring official opinions on the environment. Was it a coincidence, they wondered, that Voyager Expanded Learning, the company that made a phonics program that fit neatly within the NRP guidelines, was founded by Randy Best, a Texas entrepreneur who raised money for the Bush campaign and whose company Website once displayed a picture of Bush endorsing the program? Best sold the company for $360 million. “This is what I call the triumph of entrepreneurism over evidence,” says Richard Allington, president of the International Reading Association, a 40-year-old professional organization of teachers. “Even the NRP found only a small benefit for systematic phonics instruction—and they could not describe with any specificity what that ‘systematic’ instruction looked like.”

One critique of the NRP’s report was that it included mainly studies of struggling readers. The report’s conclusion seemed to be that every child, from a severe dyslexic to the precocious toddler plowing through all the Olivia books—must learn the same five skills in the same sequence to learn to read. But what if that’s a faulty assumption, whole-language advocates ask. If the vast majority of kids read without a problem, they say, then gearing an entire curriculum to the learning-disabled is unnecessary—and may impede other kids’ progress.

With the government’s support of phonics in place, the NRP compiled a list of so-called evidence-based programs that included an emphasis on the five basic phonics skills. Then, as part of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, the Bush administration held back funding from any school curriculum that didn’t use one of those programs. Balanced Literacy, naturally, was not on the approved list.

In New York, G. Reid Lyon, Bush’s chief education adviser and the chair of the NRP, threatened to pull $240 million in federal funding from city schools if Klein didn’t supplement Balanced Literacy with something “evidence-based.” Eventually, Klein added a small phonics program called Passport, to be used in schools alongside or in place of Month by Month Phonics. Balanced Literacy was retained as the primary reading curriculum in all but 49 of the city’s elementary schools; in the rest, Klein agreed to use Harcourt Trophies, a phonics-friendly curriculum, as the main reading program. “The city was looking to turn over no schools. And the federal government, I’m sure, wanted every school to be using an evidence-based program. Clearly there was a negotiation,” says Ravitch.

In the years after the NRP report, phonics racked up more scientific support. In the Yale MRI studies, researcher Sally Shaywitz, a member of the NRP, demonstrated that kids learning the NRP way developed their occipital-temporal parts of the brain (the part responsible for reading) more dramatically than the other children did. (Shaywitz was one of three members of the NRP to co-sign the open letter to the mayor in 2003 lambasting Month by Month Phonics.) “Learning to read used to be catch-as-catch-can, but now it is real science,” she says. “There is evidence now that if you use evidence-based teaching methods, you can really rewire the brain.” Faced with these results, Shaywitz says, it’s foolish to hang on to whole language. “If you had a program that you know works, and something else you just feel pretty good about, would you volunteer your child for the one you weren’t sure worked?”

By the spring of 2004, Diana Lam was gone, but Joel Klein went out of his way to defend Balanced Literacy. He promoted Carmen Fariña, a respected Brooklyn superintendent who had used Balanced Literacy as a teacher and principal. Fariña proudly took up the cause. But behind her bluster, Fariña seemed to understand she had inherited a PR problem. “If I could take all of our critics into our schools, you wouldn’t have people thinking the same way,” she said not long after taking the job—and she soon reached out to them. For possibly the first time, a leader of the New York schools invited some of the local evidence-based reading experts, including four of the seven signers of the 2003 open letter criticizing Month by Month Phonics, to gather for a meeting at the Department of Education. At the time, this was a little like J. Edgar Hoover inviting the KGB over for cocktails. In the parlance of the Reading Wars, it was glasnost.

Since then, the New York curriculum under Fariña has moderated a bit, carefully incorporating phonics in a way that doesn’t violate the whole-language ethos. Starting in kindergarten, children like Enami at P.S. 29 begin the school year by taking a brief diagnostic reading test called ECLAS-2. If a problem is detected, the children are sent off for “interventions,” or phonics-based instruction in small groups, in those skills. Phonics is also coming into the classroom before the intervention phase—not with every child, but in targeted ways to get specific results. At one point, when Enami was having trouble saying the word least, her teacher gave her a phonics-inspired tip: “When e comes before a, e says his name.” Enami says least with no problem now.

“We need to be centrists,” says Fariña, who has even reached out to Sally Shaywitz to study the effectiveness of a particular intervention program called Fundations. “Kids come to us in various sizes with varying needs. None of us are reading the Times on Sunday on the same page at the same pace and with the same interest, and neither should kids be doing that in their classrooms.” It seems that the NRP has found its way into the New York schools, after all, albeit through a back door.

To some phonics advocates, of course, this still isn’t enough. “How many schools is Fundations in?” asks Diane Ravitch. “Lucy Calkins has trained about 10,000 teachers. Has the chancellor made any announcements that Fundations is going to be a standard along with Balanced Literacy? I would like to hear some evidence that it’s in more than just a few schools. They have a potpourri. I’m not sure what’s standardized.”

Ravitch is especially angry because she believes New York is spinning its test scores. Advocates like Calkins cite the National Assessment for Education Progress—the so-called nation’s report card that compares all school systems’ standardized test scores to one another—to show how New York’s fourth-grade literacy scores have gone up the 7 percentage points since 2002, when Bloomberg took over the schools. But Ravitch notes that the big leap in those fourth-grade scores happened from 2002 to 2003, before the reforms were put in place. “From 2003 to 2005, there was no significant gain,” she says. What’s more troubling, she says, is that the 49 New York schools that Klein allowed to use the evidence-based Trophies program increased their state fourth-grade scores, on average, by 20 percent, double the increase of the rest of the school system.

Fariña still believes that a program front-loaded with phonics can lead to rote teaching, which in turn leads to poorer teachers. Most of all, Fariña remains devoted to the proposition that the vast majority of kids just don’t benefit from being drilled. “I want kids not only to learn how to read, I want them to want to read,” she says. “And I don’t think that all the skill and drill that’s happened over the years will lead to that if we don’t do the other piece of it.”

The fact is, New York is most likely to remain a whole-language town. Federal mandates and MRI scans aside, progressive education is part of the academic culture here.

Not that this means peace is about to break out in the Reading Wars.

“Lucy Calkins is key in all this,” says Ravitch. “If someone’s on the payroll at Tweed, you’ve got to expect they’re gonna say the current curriculum is the greatest thing since sliced bread. I mean, it’s like talking to the public-relations department.”

“The big response to Diane Ravitch,” Calkins replies, “is that we’d love to have her visit schools. She’s never visiting schools. You say to her, ‘Which schools have you seen? What do you think about what’s happening in Lauren Kolbeck’s class at P.S. 29? Can you come and look at it and tell me what you think?’ I mean, the level of work that’s happening in her room and across the city—to say they’re not learning skills?”

She stops herself. Sometimes it’s hard to talk about reading without getting caught up in the wars.

“We do have a very divided country,” Calkins says. “In lots of ways.”

AND IN THIS CORNER …

The combatants in the Reading Wars.

Mad About Whole Language

Michael Bloomberg, Joel Klein, Carmen Fariña, Diana Lam

VS.

Hooked on Phonics

Diane Ravitch, Sally Shaywitz, Sol Stern