Two fuzzy heartbeats—our doctor pointed to the black-and-white monitor of the ultrasound machine, and we both squinted and pretended to see what he was talking about. A lima bean, we thought, with a smaller lima bean next to it? Sensing that we weren’t getting it, he punched a few keys and suddenly the small exam room at Cornell’s Center for Reproductive Medicine and Infertility filled with a rapid-fire thump-thump-thump-thump: our embryos on speakerphone. So wait, it had worked? Twice? When we still didn’t say anything, our other doctor piped up: “This is good news, you guys.”

How did we feel? Relieved, more than anything, that we didn’t have to face starting all over again with fertility injections. And then … shocked that there were, in fact, two of them in there. Given that we’d done in vitro fertilization (IVF), twins were a predictable outcome. But we hadn’t allowed ourselves to believe it would actually happen.

When we decided to get pregnant, we had imagined a far simpler scenario. We had expected to control the process the way we thought we controlled everything else in our tidy yuppie lives. We felt happily married. We had pretty good jobs. We had a new apartment with an extra bedroom. Having a kid was the natural next step. In a sense, we were merely being swept up in the generational tide, but we also genuinely envied our friends with kids and liked being around them. This is what we wanted.

For ten years, Sarah had, via the Pill, put her reproductive system on hold, assuming that it would resume normal service when she wanted it to, right on cue. Which it didn’t. One minute, we were enjoying the freedom of our new married life; the next, Sarah was piling ovulation test kits on the counter at Duane Reade and being told by the woman behind her, just trying to be helpful, that Sam’s Club sells them by the case. God help us if we needed that many.

Sarah had just turned 31. There was no reason to panic. Until, that is, getting pregnant just wouldn’t happen. As the months slid by, the clichés swallowed us up. The terror of feeling you’re doomed to never have a child. The good life you’d been living suddenly seeming pointless, a waste. The self-pity. The voice-mail messages from friends calling to catch up and saying, “Oh, by the way, I have some great news.” That made us feel jealous and angry, then angry and pathetic for feeling jealous and angry. It got to the point where Sarah started to feel envious of friends who’d had abortions—because at least they knew their bodies were capable of becoming pregnant.

Our evenings at home collapsed into a variation on this theme: Sarah emerging from the bathroom clutching yet another failed test and then us sitting there in stony silence on the bed, watching Oprah reruns. What would Oprah do? She’d probably be more patient, let it ride for another six months, and relax, take a vacation. But we were beyond the point of being able to enjoy a margarita and a suntan. We needed to reassert control over our lives, and we couldn’t wait. So we took our vacation money and went to see Dr. Isaac Kligman at Cornell, a fertility specialist who had been highly recommended to us by Sarah’s OB/GYN. He led us through three rounds of intrauterine insemination (IUI), which set us back about $2,500 a pop, and then IVF, which ran us about $15,000. We organized our lives around the regular morning visits to the clinic and the scary injections (we’d developed a tag-team approach; Sarah closed her eyes and jammed the needle in, then Hugo pushed the plunger).

Sarah had two embryos implanted, praying that one would develop into a pregnancy and then a beautiful baby.

Within a matter of days, she blew up like a human balloon. Before we had the chance to take the pregnancy test, she’d gained 25 pounds so rapidly it was as if we could see her body expanding in real time. Instead of going on the head-clearing weekend away that we’d planned, Sarah was admitted to the hospital. She had “hyperstimulated” from the IVF medication, an unusual reaction that left her simultaneously bloated and dehydrated. This could only mean failure, we figured.

Our doctors had a different interpretation. This disaster, they suggested, was more likely a positive sign. Doubly positive, in fact. It wasn’t just the fertility medications that caused it. It was a high concentration of Beta-HCG, the pregnancy hormone.

Then we saw the heartbeats—the two heartbeats—and we were given an index-card-size printout of the ultrasound as a parting gift. As the news sunk in, part of us wanted to jump up and down, burst into song, embrace total strangers. Twins, holy shit! But, assuming those lima beans could be trusted, did we really want to have two at once? It’s hard enough to be the parent of a single baby. Did we have any idea what two would do to us? We decided to find out by immersing ourselves in the parallel universe of multiples, while we still had time.

Like everyone else, we’d noticed the explosion in twins—who could miss those SUV-of-the-sidewalk strollers, with the parents asleep at the wheel?—and understood that fertility treatments were behind it. But that was about all we knew.

The natural odds for twins, we learned, is one pair per 90 live births. But nature’s rules no longer apply. The twinning rate has doubled nationally over the past two decades, owing mostly to IUI and IVF, as well as the rising average age of pregnant women (the older you are, the more eggs you release). The city’s Department of Health found that the wealthier Manhattan neighborhoods have rates as high as 8 percent. But within social circles like ours, where most of the women are in their mid-to-late thirties, it practically seems like a 50-50 split. We can count five couples we know reasonably well who are expecting right now; two of them are having twins.

For women who undergo successful fertility treatments, the rate of multiples is about one in three. But it seems higher too. A friend of ours who just had twins remembers visiting a fertility specialist and examining his trophy wall of baby pictures. “I was like, ‘Cool, there’s a set of twins. And there’s twins. And … ’ It was all twins!”

Triplets, too, are on the rise, but they’re still pretty rare. Even though the rate has gone up 300 percent in twenty years, only about one in a thousand kids is a triplet.

As common as IUI and IVF have become in New York these days—Jon Stewart thanked his fertility doctor by name on the air—a stigma does remain. Oddly enough, the ones most sensitive to it are not the parents who had the treatments but the ones who didn’t. Multiples are presumed high-tech until proved otherwise.

Parents of twins, we noticed, seem obsessed with meeting other parents of twins. There’s a big networking group called Manhattan Mothers of Twins Club, which a woman named Miriam Schneider discovered ten years ago when she had her twin girls. It had about 40 members then; today, it has more than 700, and Schneider is its president. Paris Stulbach, a former producer for CNN who has 3-and-a-half-year-old twin girls, wanted a group more oriented to her Upper West Side neighborhood. Moms of Multiples now has 280 members and gets together for playgroups and massive mothers-only dinner parties (dads were originally invited but they didn’t last).

“People are used to taking the long view in life, imagining the future—next month, next year—and what they’re going to do with themselves,” says the 38-year-old Stulbach. “But when you’re the mother of twins, your life suddenly boils down to ‘Can I get through the next hour?’ It’s humbling, and nobody but another parent of twins can relate. I started this group because I felt very alone. Moms of twins feel like they’re the only ones on the planet, even though there are hundreds of us all over the place now.”

No longer a tiny harmless minority, parents of multiples constitute a threat to the singleton establishment. There are, among other things, status issues to sort out. On the one hand, you’ve got parents who wish to be recognized for their extraordinary burdens (“What’s the big deal about one baby?” one mother of twins told us. “It’s a step up from having a goldfish”), and on the other, you’ve got parents of singletons who detect an air of moral superiority. Suspicions abound on both sides. A Brooklyn mother of triplets says that when she goes to the playground, “the moms will be sitting around talking while I’m struggling to hold three babies. Once one of them said, ‘We did that, we’re done.’ And I felt like, ‘I’m a human being! How can you just watch somebody struggle?’ ”

Many parents of multiples consider themselves less neurotic because they’re not so fixated on their babies’ every blurp and bleep. The other side of that is they often don’t conform to certain sacrosanct parental standards. Though breast-feeding can be exceptionally difficult for mothers of multiples, they don’t get a pass from the nipple nazis (so many sign up for classes from Sheri Bayles, the twins lactation guru). If they enjoy the novelty of dressing their kids alike, or maybe it just happens by accident, they risk being labeled freaks. And heaven forbid they put their kids on a leash. Jay McInerney, the father of twins who are now 11 years old, remembers the looks of horror and disgust he received from other parents when he went out in the street with his toddlers tethered together. “Kids that age are genetically programmed to go running off in separate directions,” he says. “One person cannot control them. It may look inhumane, but there’s nothing humane about watching your kid get hit by a bus.”

School makes a fine battleground, too. The loose talk among parents of twins is that elite private schools don’t like to admit multiples because it limits the donor pool (nobody has hard evidence of this). When twins get older, says Nancy L. Segal, a developmental psychologist who specializes in twins, they are often accused of cheating together on tests and plagiarizing each other’s papers. The New York public-school system, like many around the country, discourages twins from being in the same class, based on the new orthodoxy that separation helps them develop individual identities. Parents are challenging that, saying those decisions should be theirs to make.

Raising multiples in New York is extreme parenting on the major-league level. There isn’t enough time, there isn’t enough space, and even for people who otherwise seem fairly well off, there isn’t enough money. “You’re overwhelmed, but you’ve got to learn to let go,” says Schneider. “Your house will never be clean, the dishes will never be done. You see this?”—she picks up a stack of color Xeroxes—“These are the holiday cards from 2001 we never mailed.”

To see what we were in for, we invited ourselves over to dinner at Bart and Elizabeth’s, acquaintances of ours who live in Tribeca with their 3-year-old twin boys. They also invited their friends Jacob and Alice, who have their own set. (To achieve maximum candor, we agreed to refer here to the grown-ups by their middle names.) The scene there looked idyllic. By 8 p.m., three toddlers in bathrobes, their hair damp from a communal bath, were sitting peacefully on the sofa with their sippee cups, absorbed in Dora the Explorer. The fourth was nearby, eating a floret of broccoli without having been bribed to do so and looking adorable in an Elmer’s Glue T-shirt.

The grown-ups, meanwhile, sat at a dinner table drinking a bottle of red wine and eating takeout from Odeon. All are in their mid-thirties to early forties, work in arts-related fields, and, in the typical New York way, had experienced most of their adulthood as extended adolescence. They spent their money on dinner and clothes, went to movies, and saw rock bands. Then they decided to start families.

Both Elizabeth and Alice went through multiple rounds of fertility treatments. Both were overjoyed to be having any babies at all and happily embraced the news of twins. And both admit that the blissful scene at the apartment tonight, with four chilled-out kids, is 100 percent anomalous. In the months following the birth of their boys, Bart says, he and Elizabeth experienced “white-hot isolation.” Living in New York, he imagined they’d be the people arriving at rock shows with their kid in a sling. “But there was no way,” he says. “You know, I’d imagined what it would be like to be the president of the United States and to be an astronaut, but somehow it never came on my list to be a father of twins.”

“Oh, it was so beyond anything I’d imagined,” says Alice. “On the one hand, it’s unbelievable joy and it’s everything you wanted and you wanted so badly to have these kids. But I was just remembering those moments where it’s Saturday morning and you’ve each slept about half an hour a couple of times during the night and you’re each holding an upset baby and you say, ‘Can I give you both babies so I can brush my teeth?’ And your husband’s like, ‘No, I’ve been waiting for two hours to make the coffee,’ and you’re like, ‘Well, can I just take my puked-on shirt off?!’ And he’s like, ‘No! I have to pee!’ And you know that there’s, like, fifteen hours ahead of you before bedtime where nobody’s going to get sleep again.”

For a moment, no one at the table says anything.

Multiples put considerable strain on a marriage. “Basically, the wife hates the husband,” says Jacob. Alice cuts in: “You say to your husband, ‘Why can’t you save me from this? Why aren’t you helping me?’ ” It doesn’t matter how much the husband might be helping. Or think he’s helping.

“It’s what all first-time parents feel,” says Elizabeth, “but more.” With twins, Bart grew more attached to his urban life, while Elizabeth set her sights on Austin, Texas, and a yard. Why stay in an expensive place where you can’t take advantage of the good things it has to offer? she figured. No one was exactly getting to the theater much.

Part of what kept the couple in the city, or what made the city manageable with their multiples, was their relationship with Jacob and Alice and their boys. Bart and Jacob were college friends who had fallen out of touch. Then they ran into each other in Union Square a few weeks after their boys were born. “I was in a fog,” remembers Bart. “I said, ‘Hey, what’s up, man?’ ‘Nothing, just had twins.’ ‘Twins?! Me too!’ We made plans to hang out, which never happened. Then six months later we ran into each other again and had the same exact conversation. ‘Hey, what’s up, man?’ ‘Nothing, just had twins.’ ‘Twins?! Me too!’ ”

That second meeting, though, led to an immediate plan. Wives were called, twins were loaded into Urban Mountain Buggies, and all eight of them convened at Bar Pitti, rediscovering the thrill of daytime drinking. “It was the first time we’d done anything like that, socialize, eat at a restaurant,” says Elizabeth. “It was a total revelation. And our boys all fell asleep at the same time.”

As they endure the peculiar rites of extreme parenting on the same schedule, they’ve found many things to be true: There are Hallmark moments that you will never experience if you have two, like hovering over the side of the crib marveling as the baby arches an eyebrow. Breast-feeding is an endless loop until you finally quit. Friends come over once and then don’t come back. “You really need four parents to take care of two kids in the same manner two parents relate to a singleton,” says Jacob. “You always feel split,” says Alice, “like you’re shortchanging someone. You find yourself running back and forth with compliments or toys to create a level playing field as best you can.” Still, no matter how much you try to treat them the same, their own conflicting traits emerge—one sleeps through the night, one demands love every hour.

Then there are the episodes you never forget. One morning when Bart was trying to let Elizabeth sleep in, a twin made a big poop. While Bart was changing the dirty diaper, the other one grabbed the poop with the clear intention of sticking it in his mouth.“It happened so fast,” says Bart, “like in a John Woo movie where suddenly everyone’s pointing guns at each other.” With a semi-free hand, Bart grabbed the would-be poop-eater’s arm and the three of them just looked at each other frozen in place. “I had to think eight moves ahead,” says Bart. “I actually said out loud, ‘Okay, what am I willing to sacrifice?’ I can’t let him eat the turd. So, somehow I swung the kid with the turd onto my shirt, which was now going straight to the garbage. When Elizabeth came out ten minutes later, I looked like I’d been in a car accident.”

In the midst of telling another twins war story, Elizabeth nudges Alice. “Remember, we were going to try not to scare them,” she says, referring to us. Too late. We saw enough of ourselves in these two couples to be deeply concerned. Much as they’d wanted children, their lives had simply not been built for them. And neither, at that point, were ours.

When one of our friends found out she was pregnant with twins, she was anything but thrilled. “I would say I was stricken,” she says. “I walked around in a depressed daze. When you tell people you’re having twins, they laugh and say you’re in for a ride, and I actually got really angry a couple of times. It’s not funny. It’s a much-higher-risk pregnancy and it’s a really big deal and it’s not what I wanted.”

Carrying multiples is an endurance test, psychologically and physically. The risk of pre-term labor hangs over you all the time. You get big, really big. The maternity clothes Sarah bought at twelve weeks were painfully snug by twenty weeks. At 24 weeks, strangers in elevators would blithely ask, “Any day now, huh?” (She’s become incredibly careful about what she says to strangers in elevators.) Terri Edersheim, her high-risk obstetrician, had forbid exercise of any kind. Even light arm weights, Edersheim argued, would increase her uterine activity and possibly cause contractions, a very bad idea. A cute pregnancy full of prenatal yoga and high heels became another fantasy that Sarah had to let go of.

So we had what you could call a data-driven pregnancy. We went in for a million ultrasounds. We took every test. Edersheim even sent us to Boston to see a 3-D ultrasound specialist whom she considers the best in the business. In addition to creeping us out with images of our precious babies looking like space aliens, this ultrasound yielded two important pieces of information. First, it confirmed that we were having two girls; at a previous ultrasound, a technician said it looked that way to her but it was too early to be sure. For whatever reason, that was the one combination we hadn’t considered, and it was hard to absorb at first. It wasn’t that we didn’t want two girls—we just never thought that’s what we’d get.

The other news had much more serious implications: Baby B had a “soft marker” for a deadly chromosomal disorder called trisomi 18. That necessitated a trip to a genetic counselor back in New York who walked us through a bewildering array of scenarios that included a “reduction” of the pregnancy to a singleton.

We’d never heard the term reduction, but as we looked into it, we discovered that it’s become a major feature of the techno-fertility process. When women come out of IUI or IVF more pregnant than they want to be, they see a practitioner like Mark I. Evans, a 54-year-old obstetrician and geneticist who works out of a townhouse in the East Sixties. Though he’s been doing this for more than twenty years, he still has a cowboy mentality. “We do some pretty bizarre shit,” he says. “I’ve seen women pregnant with septuplets, octuplets. My record is twelve.”

In the midst of telling another twins war story, Elizabeth nudges Alice. “Remember, we were going to try not to scare them,” she says, referring to us. Too late.

Back in the early eighties, when Evans was a young professor at the Wayne State Medical School in Detroit, he thought he knew how to stop the heart of a single fetus without harming any others in the womb. It involved an injection of highly concentrated potassium chloride. He didn’t use it on a human patient until he received a call from a physician treating a four-foot-ten woman pregnant with quadruplets. The doctor had recommended to her that she get an abortion, but having spent seven years trying to get pregnant, she asked if there was such a thing as “half an abortion.” Evans thought he could do that for her, and when he did, his medical career began its strange odyssey to the present day. “I turned those four into two, and they’re out of college already,” he says. “Then I got a call from a lady in Alaska who had octuplets. She was a little taller, but even King Kong couldn’t carry octuplets. So we turned her into two, and those kids are in college. By now, I’ve done thousands of patients.”

On the day we went to his office, Evans was wearing aqua-green scrubs and a nice gold watch. On the wall, he had pictures of himself with Phil Donahue, Diane Sawyer, and, of all people, Pope John Paul II. Evans sees himself as a crusader for the cause of rational family planning. “Our goal—and here’s your sound bite—is healthy families,” he says. “It doesn’t matter how many. When I first started this thing, nobody except for the most fundamentalist of folks had a problem reducing four or more, because the outcomes were so horrible.” he says. “So the ethical debate was triplets. People were claiming, ‘Oh, you don’t reduce triplets, they do so great.’ But the data doesn’t support that. The average gestational age is three weeks earlier than twins, and the perinatal mortality rate is considerably higher.”

Over the years, as three-to-two reductions became routine for Evans, he slowly approached a new threshold. What about going all the way down to one? He’d done it, of course, but only out of medical necessity. Now, he admits, it had become “more a matter of lifestyle. The typical story is, second marriage for both, he’s got two kids from his marriage, she’s got two from hers, they just want one of their own.”

Two years ago, the feminist Amy Richards told The New York Times Magazine about her decision to reduce the triplets she was carrying. She rejected the option of twins as still too much of an imposition and health risk and had her doctor reduce her pregnancy to a single fetus. Predictably, she was excoriated by right-to-lifers. What was more surprising was the relatively conflicted reaction she received from the pro-choice side. A decision like hers made people uncomfortable, like a kind of yuppie eugenics.

Even the freewheeling Evans tones down his rhetoric when he explains his decision to do the two-to-one procedure. “When you start doing anything radically new, you start with the life-and-death situations,” he says. “You start with the nothing-to-lose cases. As with every technology, as the risks and benefits get better known, those indications liberalize. I came to the ethical conclusion that if you believe that one-to-zero is ever acceptable—i.e., that a woman should be allowed to have an abortion—then why not two-to-one? I came to believe it was a valid choice.”

Fewer and fewer are likely to be put in that position, though. IVF technology is improving to the point where doctors can better identify the hardier embryos so they don’t have to stack the deck by implanting more than one. “We’re almost at the point where we can consider single-embryo transfers,” says Jamie Grifo, head of the reproductive-medicine program at NYU Medical Center. “The Europeans are already doing that. But you can’t always control the process even then. I had a patient who was terrified of having twins. So I said fine, and we put in one embryo. Guess what? They split. She got twins.”

As for us, reduction ceased to be a consideration as soon as we did an amniocentesis test and it came back clean. But the brutal little detour had an unintended benefit. The fear of losing one brought us to terms with how intensely we wanted both of our little girls.

Even as reductions have become normal, there are people who still try for triplets and quadruplets, and not all of them are fundamentalists. Karyn Geringer is a 34-year-old marketer for a hedge fund, and she lives with her husband, John, an engineer, on the East Side. They did IVF, came out with triplets on the third try, and never thought seriously about not having them all. “We always said we wanted three kids, and then there I was, pregnant with triplets,” says Karyn. “I was pretty psyched about it. You talk to your family, friends, they’re like, ‘What?! You’re crazy.’ I wasn’t focused on the risks. I wanted three, and I had them.” They arrived at 30 weeks in March, and after a series of ups and downs, the last of them made it home from the hospital last week.

Two years ago, Jean-Marie Kennedy, a 33-year-old schoolteacher from Windsor Terrace, decided to go to term with quadruplets. She, too, had done IVF, and her doctors all but insisted she reduce. Jean-Marie says she and her husband, Morris, did not disbelieve the doctor’s warnings about the risk of blindness, for instance. But she did some research and came to her own conclusions. “We read, like, 70, 80, 90 cases online, and the complications never happen,” she says. “I mean, scientifically, it’s real. I’m sure it does happen. But anecdotally, we couldn’t find it.”

On that slim reed of hope, they made their decision to keep them all, even after it became apparent, early on, that one, a girl, was lagging behind the others. At nineteen weeks, Jean-Marie stopped working and went on prescribed bed-rest. By 29 weeks, she weighed 60 pounds over her normal weight and was so stuffed she could barely eat. Her blood pressure suddenly soared, and the babies had to come out. The boys, Lukas and Nathaniel, were a decent size for 29-week preemie quads, weighing three pounds, eight ounces. One of the girls, Mikayla, was worse off at two pounds, seven ounces. The fourth child, Isabella, was dangerously little, one pound, four ounces.

All four were rushed into Methodist Hospital’s neonatal intensive-care unit (NICU), where they were placed in incubators. The boys spent six weeks there, Mikayla a week longer. Isabella never made it home. She stayed on for seven months at Methodist and then was transferred to the NICU at Columbia-Presbyterian, considered the city’s best. There, doctors delivered a grim prognosis to the Kennedys: Her lungs had been seriously weakened by repeated infections, and she would be gone in a matter of days. With Jean-Marie back home taking care of the other kids, Morris held tiny Isabella in his arms for most of her last night.

Jean-Marie couldn’t afford to go into the paralysis of mourning like most mothers who lost a young baby would. “There was a lot of work to be done,” she says. “My kids needed me. Everything kept going.”

The family never moved from their one-bedroom apartment, which is on the sixth floor of a building with a bad elevator. The living room is given over to a penned-in play area, with the three cribs lined up against one wall. “We used to have a couch, a bookshelf, normal stuff,” says Jean-Marie. “But they need the space more than we do.”

Fortunately, triplets tend to be well behaved. They have no choice. They understand early on that because the babies outnumber the parents, screaming in the crib won’t necessarily bring a response. So their sleeping schedule tends to stabilize quickly. A similar discipline takes hold for eating—if they don’t take whatever food is offered, their siblings surely will and they’ll go hungry. “We don’t have to mess around with ‘Open up for the flying airplane,’ ” says Jean-Marie. “It’s a total assembly line.”

To get by, the Kennedys rely on neighborly generosity. They receive a steady flow of hand-me-down clothes and toys from Park Slope moms, and a nun comes over once a week to help Morris when he’s responsible for the kids. A local Catholic school held a fund-raiser for them. Although the children seem like healthy, vigorous toddlers, they’re behind on their milestones, not unusual given their prematurity, and they qualify for as much therapy as they need through the state’s Early Intervention program. Even with all that, Morris has to work three jobs, teaching photography at a private school on the Upper West Side, substitute-teaching in the city’s public schools, and driving a cab on the weekends.

The Kennedys lead a complicated life that few would envy. Jean-Marie dreams of having a nanny in just long enough for her to read the Sunday Times in bed. If we try to put ourselves in their shoes, we can’t do it. But they exhibit no trace of self-pity or regret over surrendering their personal lives to their children. “I look at it this way,” Jean-Marie says. “In ten years, the kids will want us out of their way. And then maybe Morris and I will get back to doing some of the things we used to do.”

Or maybe it will be longer than that. Morris says he might like to have more children. “They say that in three years, women forget about how hard the pregnancy was and they’re willing to do it again,” says Morris. “It may take Jean a little longer than that. But I’ll be ready if she is.”

Everything’s fine and then suddenly everything gets complicated. At week 32, Sarah goes in for a routine stress test that shows no signs of contractions. She comes home, makes herself dinner, sits down to watch The O.C. (the prom episode) with her friend Ondine, and her water breaks. They say there is no mistaking it, and that is true. Ondine goes running downstairs to fetch Hugo from the gym; he sees her blonde head coming through the gym door and he knows instantly what must be happening. Ondine hails us a cab. We rush to New York Hospital, where the contractions start coming hard and fast. Sarah asks everybody who looks like they might be a doctor or a nurse why this is happening. What had she done wrong? Should she not have made dinner? She wants an explanation.

Baby A’s head is pointing south, in the proper position, but Baby B is lying east-west, which puts her at risk of breach. So we’re going Cesarean. Sarah is convinced we didn’t make it long enough and that our girls are in danger.

They give her an epidural, load her on a gurney, and wheel her into the operating room. She is still asking for an explanation as the doctors swab her stomach and a nurse covers her arms with a blanket. The procedure goes quickly. Hearing a few muted cries, Sarah wants to know, “Do they look like babies?” Hugo peers around the curtain that blocks Sarah’s view of her own insides, but all he can see are one baby’s feet. “The feet look good,” he tells her. “Not too tiny.” The weights are announced: Baby A, a.k.a. Scarlett, is three pounds, fourteen ounces; Baby B, a.k.a. Orly, is four pounds, two and a half ounces.

Our lives go into slow motion. The girls are taken to the NICU, where they are placed in clear plastic incubators called Isolettes, while Sarah recovers in a hospital room upstairs. Being in this situation was our biggest fear all along, the situation of the babies’ being not okay. We thought if we did everything right—if we did the injections properly, if Sarah rested and ate well and rested some more—then we could will them into existence. When the nurse takes Scarlett out of her Isolette and lets Sarah hold her for the first time, the numbness that enabled Sarah to climb out of her hospital bed is broken by how terrible she feels that our little girl has to go through this alone.

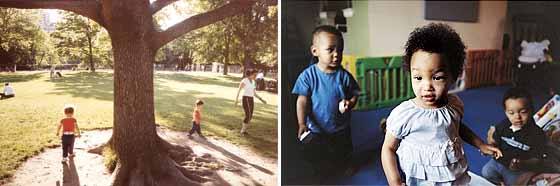

And then, over the next few days, it all starts to turn. Though we are allowed to stay with them as long as we wish—and can feed them and change them and bathe them—we are largely spectators to their incredible resurgence. Scarlett and Orly are upgraded to the “feeders and growers” category, advanced placement in the NICU. We watch with pride as four-pound Scarlett requires two nurses to hold her little arms down so they can get her IV back in. One day we arrive at the NICU to find our girls reunited in a single incubator. In baggy white kimono undershirts, they’ve both rolled to the inside so that their foreheads are touching. It is clear that somehow they are giving comfort to each other, and all that distress and worry we had been hoarding over the last two years washes away. How could we have ever had less than these two?

A month goes by, slowly, and then we get a couple of days’ notice that the girls are well enough to go home. We surprise ourselves by not freaking out. Yet. As we write this, they are coming through the door.

BABYMAKING 202

The evolution of the Bernard-Lindgren twins, from pre-transfer IVF embryos (September 29, 2005) to their eleven-week mark in utero (December 13, 2005) to, finally, at 33 days old, Scarlett and Orly at home(May 31, 2006).