On Monday, September 10, 2001, Sneha Anne Philip had the day off. After her husband, Ron Lieberman, left for work at about eleven, she had their sunny, one-bedroom Battery Park City apartment to herself. Just her and the kittens, Figa and Kali. She planned to spend the day tidying up—the apartment was a mess, and her cousin Annu was coming over for dinner on Wednesday. She repotted four purple-and-white orchids that had arrived from Hawaii and placed them in the bathtub to dry out. At about 2 p.m., she sent her mother an instant message that mushroomed into a two-hour electronic conversation: “You should have seen Ron play guitar this weekend!” On Saturday, they had gone to a party where Ron, an emergency-room intern at the Jacobi Medical Center, jammed until midnight with his co-workers. Sneha also wrote about her plans for the week. She’d been wanting to check out Windows on the World, where an old friend was getting married in the spring. Finally, about 4 p.m., Sneha signed off so she could run some errands.

The 31-year-old internal-medicine intern changed into a brown short-sleeved dress and sandals, her black hair pulled back in a ponytail. After dropping off some dry-cleaning, Sneha headed to Century 21, the discount department store a few blocks from their apartment, just past the Twin Towers. Just after 6 p.m., she used Ron’s American Express card to buy lingerie, a dress, panty hose, and linens. Then she headed next door to the shoe annex and bought three pairs of shoes.

Ron came home from work that night to an empty apartment. Although it was almost midnight, he wasn’t all that surprised. Sneha was supposed to call when she stayed out late, and she hadn’t. Again. He petted Figa and Kali and went to bed. He had to leave for work by 6:30 A.M.

When his alarm clock went off Tuesday morning, Sneha still wasn’t home. Ron was irritated, though still not particularly worried. Perhaps she’d spent the night at Annu’s place a few blocks away or ended up in the West Village with her brother John—she did that sometimes. Resolving to talk to Sneha once more about her habit of staying out all night without checking in, he sleepily made his way to the Bowling Green subway station, where he caught an uptown 5 train in time for his 8 A.M. meeting at Jacobi in the Bronx.

When the meeting ended at nine, Ron saw his co-workers gathered around a television. A plane had just struck the north tower of the World Trade Center, about two blocks from his apartment. He called home immediately—Sneha didn’t have a cell phone—and got the machine. He left a number of messages that morning, but Sneha never called back. He called her mother and brother—neither of them had heard from her, either.

Now Ron was worried. The city was in chaos, and he had not spoken to his wife since he kissed her good-bye the previous morning. Where was she? Because Sneha had no reason to be in the Trade Center, the possibility that she was trapped in the towers barely crossed his mind. But other horrifying images ran through his head: Had she been kidnapped off the street while running errands Monday afternoon? Had she been hit by a car and sent to a hospital, unidentifiable without her I.D.? Had she stopped for a drink on the way home and sidled up to the bar next to the wrong stranger?

At 3 P.M., Ron decided to stop wasting time waiting at Jacobi for the Twin Tower casualties that never materialized and to hitch a ride downtown with an ambulance to look for Sneha. The ambulance ride, against the stream of frantic people fleeing lower Manhattan, took six hours. When he finally reached Tribeca about 9 P.M., the NYPD had cordoned off the area. Still wearing his scrubs, he talked his way past the police line, then raced past burning cars and overturned fire trucks toward their Rector Place apartment. Without electricity, the front doors to the 23-story building wouldn’t open. Eventually, he gave up and walked to a friend’s place in the West Village, where he spent a sleepless night on a couch before heading home early the next morning. This time, he got inside. Gray soot from the fallen towers had poured in through an open window. Paw-print trails from the kittens crisscrossed the floors, but there was no sign of Sneha. No one has seen or heard from her since.

More than 9,000 people were reported missing on September 11, though the NYPD quickly whittled down the list. Officials discovered names that had been listed more than once. People called to say they had heard from “missing” loved ones. Investigators uncovered numerous cases of fraud. But years later, a few stragglers remained, people whose fates had never been resolved. Did they die on September 11? If not, what happened to them? In January 2004, the medical examiner’s office announced that it was removing the last three names from the list of 9/11 victims, leaving the total at 2,749, where it still stands. Sneha’s was one of those three names.

For the Philips, the loss was almost as painful as the first. Every young person who dies becomes an angel in memory. Soon after Sneha disappeared and presumably died in September 2001, her family began the beatification process: She must have run into the burning towers to use her medical expertise to try to save lives. She must have died a hero. But something got in the way of their efforts to shape their memories, to simplify the complexities of a life. City officials believe that Sneha led a secret double life. According to court records, her struggles with her dark side had cost her a job and damaged her marriage and may have led to her death the night before the terror attacks. But as the fifth anniversary of 9/11 approaches, Sneha’s family is still trying to shape her legacy. They are still trying to prove that she died virtuously, one of the glorified 9/11 victims.

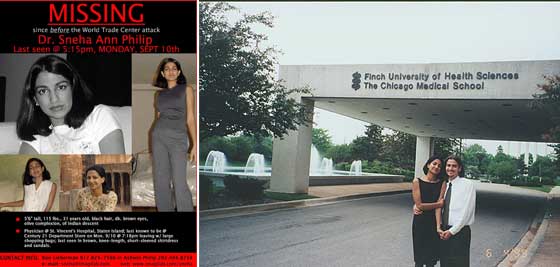

Sneha and Ron met in 1995 at Chicago Medical School. She was a pretty and gregarious Indian girl who had grown up in Albany. He was a Jewish boy from L.A. with shoulder-length hair and a goatee. She was an artist, he played guitar—they stood out among their medical-school classmates and before long started dating. Sneha was a year ahead of Ron in school, so when things got serious, she took a year off, traveling around Italy, to let him catch up.

The couple graduated in 1999 and landed internships in New York—Ron at Jacobi, Sneha at the Cabrini Medical Center in Manhattan. They found a roomy, dark one-bedroom apartment on East 19th Street and began to build a life together. They worked interns’ hours but still found time to spend with each other. They favored the jazz clubs of Greenwich Village and hole-in-the-wall sushi joints near Gramercy Park. Their life suited Sneha. She was near her brother, who lived on Greenwich Street, and only an hour-long train trip from her parents, who now lived in Dutchess County.

In May 2000, the couple got married in a Jewish-Indian celebration before 250 guests at a Dutchess County inn. At the end of the ceremony, Ron placed around Sneha’s neck a gift from her mother: a teardrop-shaped gold minnu, the traditional Indian wedding pendant. At the reception, he had the band play a jazz tune he composed for the evening titled “Wow! She’s So Great.”

Less than a year and a half later, Ron was walking the streets with photocopies of his wife’s picture. The day after the attacks, he went to the 9/11 help center at the Lexington Avenue Armory to drop off flyers. When he saw the television cameras, he thought he might be able to get Sneha’s picture out all over the country. He hoped someone would recognize her and provide clues about her disappearance. But when reporters learned that Sneha had not been heard from since the 10th, they lost interest. They wanted real 9/11 stories. Though Ron still did not believe his wife had been in the towers, he was desperate. He called Sneha’s brother and suggested he come down to talk with reporters, leaving out a few details.

John took it one step further. Although he had been fighting with Sneha and had not spoken with her in two weeks, he concocted a scenario of her final moments, live on WABC. Staring mournfully into the camera, he said, “I was on the phone with her, and she told me she couldn’t leave because people were hurt. She said, ‘I have to help this person,’ and that’s the last thing I heard from her.”

The lie worked, and WABC ran a picture of the flyer. But no leads were uncovered, no witnesses found. As time passed, John began to worry that he had led investigators down the wrong path, preventing her from being found. “Maybe if I didn’t do it … maybe it would have gone another way,” he told me. “It became a hero story.”

The hero story notwithstanding, the family’s initial search focused on the 10th, which at the time seemed more hopeful than the alternative. Ron, who spent much of 9/11 waiting in vain to treat the injured, knew as well as anyone that survivors were unlikely to emerge from ground zero. Whatever may have occurred on the 10th, at least Sneha might still be alive.

Ron approached the crisis methodically, like a physician. His first clue came from Sneha’s instant messages on Monday to her mother: She left the house in the late afternoon to run errands. Then Ron called American Express and learned of the Century 21 purchases. (Hoping it may yet provide a lead, Ron has kept his AmEx account open.) The downtown Century 21 had temporarily closed, so he dispatched friends to drop off flyers at its other branches. Later that week, he received a phone call from Sonia Mora, a shoe-department salesclerk who had been relocated to Brooklyn. Mora said that she recognized Sneha as a Century 21 regular. Sneha came to the store with a friend on the 10th, she recalled, describing the other woman as small, in her early thirties, dark-skinned, possibly Indian. The shoe department did not use security cameras, but—after spending three weeks alone in a windowless room at Century 21’s offices reviewing videotape—Ron discovered a coat-department video from an hour earlier that captured Sneha browsing alone. Sneha’s mystery friend—if she existed—was never found.

Ron filed two missing-persons reports, but detectives—after ruling him out as a suspect—appeared inclined to lump Sneha in with the World Trade Center victims, he says. So Ron hired a private investigator, former FBI special-operations agent Ken Gallant, who scoured Sneha’s favorite hangouts, interviewed employees at bars and hotels near Century 21, and talked to Sneha’s friends, family, and co-workers. Gallant brought photos of Sneha to ferry docks, looking for people who remembered her fleeing on the 11th or being dragged out on the 10th. He even recommended a psychic whom the family flew in from Pennsylvania.

Gallant also raised the possibility that Sneha might be alive and living a new life somewhere. He oversaw a forensic examination of Sneha’s computer, searching for evidence of a secret lover, an upcoming tryst. But he found nothing, and the fact that Sneha left behind her glasses, passport, driver’s license, and credit cards (with the exception of Ron’s AmEx) seemingly ruled out the theory that she intentionally disappeared.

The search did unearth a few clues about Sneha’s final hours. Although Ron was the only one home on the night of the 10th, someone made a call from their home phone to his cell at about 4 A.M. Tuesday, he discovered. He doesn’t remember making the call but figures he may have sleepily checked his messages. Because Ron found neither footprints in the dust nor the Century 21 bags, he knows Sneha never came back to their apartment after the terror attacks. But the most tantalizing clue came from the apartment building’s security camera: a videotape of a woman who resembled Sneha in the lobby just before the first plane struck the Trade Center. Because of the angle of the sun, the image is too bleached out for Ron to be sure. But on the tape, a woman who in silhouette looks very much like Sneha—a similar haircut, similar mannerisms, wearing a dress like the one Sneha wore the afternoon before—enters the building. She stands near the elevator, waits a minute or two, then turns around and leaves.

Faced with this dearth of meaningful leads, Ron and the Philips began to reevaluate their hypothesis that whatever happened to Sneha happened on the 10th. “These kinds of crimes don’t happen in lower Manhattan, that somebody goes missing from a homicide, and they don’t find the body,” Ron says. “Killers are usually stupid, they leave clues. A body will come up. Sneha just vanished. Vanished, vanished, vanished, with no trace. The only thing that makes sense is that she burned in the World Trade Center.”

A story of a heroic death—a story very much like the one John made up for the television cameras—took root. Perhaps that was Sneha on the videotape. Perhaps she went shopping, bumped into the friend whom the salesclerk remembers, went out for drinks, and, thinking that Ron would be working late, ended up spending the night at her place. Perhaps Sneha returned home the next morning, was in the lobby when the plane struck, and, as a doctor, reflexively ran toward the towers to help. The theory had flaws—the woman on the tape, for example, was not carrying shopping bags—but it fit perfectly into the family’s idealized image of Sneha, the version of her they hoped to remember.

This account of Sneha’s death also gained the Philips entry into the special community of grief surrounding 9/11. They no longer had to suffer alone. On the first anniversary of the attacks, Sneha’s parents went with their two sons and Ron to a memorial in Poughkeepsie, where Sneha’s name was read aloud as part of a tribute to local victims. Three days later, the Philips held a small ceremony at the Church of the Resurrection, near their home in Dutchess County, where they buried an urn filled with ashes from ground zero. A few months after that, a plaque went up in a grove at Dutchess Community College, where Sneha’s mother, Ansu, works as a computer programmer, that reads DR. SNEHA ANNE PHILIP, OCTOBER 07, 1969–SEPTEMBER, 11, 2001. By 2003, attending memorials had become a routine for the family, an opportunity to discuss their loss with others whose loved ones were heroes and martyrs. That October—intent on creating a memorial fund, he says—Ron filed a claim with the Victim Compensation Fund.

But as the Philips were coming to the conclusion that Sneha died in the Trade Center, another investigation was going on. Although the police had initially considered Sneha a 9/11 victim, they later uncovered a very different version of her life—one that makes her family very uncomfortable.

Police reports and court records describe a life that was reeling out of control in the months leading up to Sneha’s disappearance. Citing tardiness and “alcohol-related issues,” Cabrini’s director of residents had informed Sneha in the spring of 2001 that her contract would not be renewed—for interns, the equivalent of being fired. Shortly thereafter, Sneha got into a dispute at a bar that landed her in jail for a night. She claimed that on an evening out with co-workers, a fellow intern grabbed her inappropriately. She filed a criminal complaint, but after conducting an investigation, the Manhattan D.A.’s office dropped the charges against the alleged groper and instead charged Sneha with filing a false complaint. The prosecutors offered to drop the charge if Sneha recanted, but she refused. She was arrested and spent a night behind bars, where she meditated with a cellmate.

Sneha was also experiencing “marital problems” in the months after she was fired from Cabrini, according to court papers, and “often stayed out all night with individuals (not known to her husband) whom she met at various bars.” She favored the loungy midtown lesbian bar Julie’s, the rocker-dyke bar Henrietta Hudson’s, and the divey gay rock club Meow Mix. According to the investigations, Sneha’s indiscretions appear to have reached a low point in the month prior to her disappearance. A police report says that her brother John walked in on her and his girlfriend—now the mother of his son—having sex. Her alleged struggles with depression, alcohol, and her sexuality spilled over into her new job as well. Staten Island’s St. Vincent’s Medical Center suspended her for failing to meet with her substance-abuse counselor.

Apparently these problems reared up again on the day she disappeared. Sneha had a court date on the morning of September 10, 2001, where she pleaded not guilty to the charge of filing a false complaint. Ron went with her before he left for work. According to the police report, the couple got into a “big fight” at the courthouse because Ron was upset that Sneha “was abusing drugs and alcohol and was conducting bisexual acts.” In this account, Sneha stormed out of court, leaving Ron behind.

Unable to tie Sneha’s death to the attacks, the medical examiner’s office removed Sneha’s name from the official list of 9/11 victims in January 2004. “This particular lady was known to be missing the day before,” explains Ellen Borakove, the medical examiner’s spokesperson. “They had no evidence to show that she was alive on 9/11.” And in November 2005, a Manhattan judge denied Ron’s petition to set Sneha’s date of death on September 11, 2001. Judge Renee Roth ruled that Sneha officially died on September 10, 2004—as set forth by state law, three years to the day after her “unexplained absence commenced.” Because Ron could not produce a 9/11 death certificate, the Compensation Fund denied his claim. Based on Sneha’s age and potential earnings, the claim would have been worth about $3 million to $4 million, according to an attorney who represented numerous other families who sought compensation.The police still don’t know what happened to Sneha, but the implication of the court decision is obvious: Sneha was just as likely to have left her husband, committed suicide, or even been the victim of a violent crime as to have rushed into the World Trade Center on 9/11.

Although he hadn’t spoken with Sneha in weeks, her brother concocted a story live on TV. “I was on the phone with her, and she told me she couldn’t leave because people were hurt. She said, ‘I have to help this person,’ and that’s the last thing I heard from her.”

Sneha’s family—Ron, John, and her parents, Ansu and Philip—dispute essentially everything in the police and court accounts. The event that precipitated Sneha’s decline—being let go by Cabrini—had nothing to do with alcohol, they contend. Instead, they claim Sneha was the victim of persistent racial and sexual bias at Cabrini and was dismissed because she was a whistle-blower. (A spokesperson for Cabrini says they have “no knowledge of any sexual harassment allegations made by Dr. Philip.”)

Ron admits that Sneha had gone home with women she met at bars but claims that her actions were innocent of the obvious implication. Sneha liked to see live bands and to have an occasional drink, and she preferred to do so at lesbian bars, where men would not hit on her—particularly after the groping incident, Ron says. She spent a few nights with women she met out on the town, but they talked or made art or listened to music until they fell asleep, he insists. One night, he recalls, Sneha met an artist at a bar and the next morning she came home covered in paint. “These allegations of her being bisexual are ridiculous,” Ron protests. “Because we don’t live a conservative lifestyle doesn’t mean that anything abnormal is going on. I’m a musician. I’ve been going out to bars and clubs my whole life. It doesn’t mean these things are dangerous activities.”

John claims that the missing-persons report, which states that he told Richard Stark, the detective assigned to the case, that he walked in on his sister and his girlfriend having “sexual relations,” is simply untrue, a product of cops sitting around playing Mad Libs. He maintains that he never even spoke with Stark, who has since retired and could not be reached for comment. Ron also says the report is riddled with fabrications. The fight at the courthouse, for example, never took place, he says. “Either I’m a liar or they’re lying, because I’m 100 percent positive about this,” he says. Ron and John offer little to explain what would motivate the police to lie. Mainly they suggest that investigators needed to compensate for their ineffectual police work by wildly extrapolating from the few facts they uncovered. (An NYPD spokesperson said that he was reviewing the case but could not comment at press time.)

In the family’s version of Sneha’s final days, little had changed from the halcyon times of just a year or two earlier. Her drinking was merely a short stint of self-medication during a hard time. The depression was temporary and on the mend. The career was back on track, her recent suspension notwithstanding. The nights spent at the homes of random strangers were not illicit, just inconsiderate. And then, just when she was putting her life back together, she disappeared.

Perhaps Sneha’s family is trying to protect her, and themselves, from a truth that would taint her name and their memory. Perhaps they simply do not know about her other life, the one detailed by investigators after she went missing. Perhaps, though it seems unlikely, the police conjured up a wild story out of thin air. Ron refused to allow me access to the private investigator’s report, which might have corroborated or refuted the police account.

But as Ron puts it, “even if she did all these things, it doesn’t explain what happened.” No matter how Sneha spent the last months of her life, her family might be right about how she spent her last moments. At any given time there are approximately 3,000 active cases of missing adults in New York State, so people do, it seems, sometimes just disappear. But a murderer pulling off a perfect crime on the same day that 1,151 people (the number of 9/11 victims whose remains have never been discovered) also disappeared without a trace seems an extraordinarily unlikely coincidence. Even Detective Stark eventually testified in the death-certificate proceedings that he thought Sneha probably died in the towers.

Under New York law, establishing that a person died as a result of 9/11 requires clear and convincing evidence of the person’s “exposure” to the attack. But application of this law has been uneven at best. A Manhattan judge rejected a petition filed on behalf of Fernando Molinar, even though Molinar called his mother on September 8, 2001, told her he was starting a new job at a pizzeria near the World Trade Center, and was never heard from again. A Dutchess County judge, on the other hand, ruled that Juan Lafuente, who worked eight blocks north of the towers, did in fact die in the attack. During Lafuente’s death-certificate proceedings, his wife, Colette, the mayor of Poughkeepsie, presented no direct proof of her husband’s whereabouts on 9/11. Her circumstantial evidence included the testimony of a witness who frequented the same deli as Lafuente and claimed he overheard Lafuente tell a brown-haired man about an upcoming meeting at the Trade Center.

Sneha’s case contains a number of parallels to Lafuente’s. Both stories have red flags: Sneha and Lafuente each lost a job, suffered from depression, and spent a night or two away from home each month, according to their spouses. Both victims also might have been tempted to rush into the burning buildings: Sneha was a doctor and Lafuente a volunteer fire marshal. One factor, however, distinguishes Colette Lafuente’s successfully expedited death-certificate application and Ron’s four-and-a-half-year mission, Sneha’s parents believe. “Ron’s not the mayor,” says Ansu.The other difference: Sneha was a woman who allegedly engaged in an illicit lifestyle. The family’s attorney, Marc Bogatin, calls her death-certificate ruling moralistic and illogical. The decision implies that Sneha was “partially at fault for her own death for participating in this high-risk and immoral behavior,” he says. “It’s like she walked into a courtroom in the fifties.”

For Sneha’s family, the 9/11 death certificate would represent proof of what, disturbingly, has become the best-case scenario. “All her parents and I really want is for her name to be on the list,” Ron says. “End this family’s suffering right now. Her mother’s crying all the time. Is it going to hurt anybody to do it? But for some reason they’re not going to do it.”

At the Philips’ quiet, spacious home on top of one of the highest hills in Hopewell Junction, there are pictures of Sneha everywhere. In the den hangs her portrait, on the living-room wall a picture of Ron and Sneha at their wedding. On the mantelpiece above the fireplace sit another half dozen pictures of her—Sneha in her wedding gown, Sneha receiving a diploma, Sneha and Ron standing in the kitchen—and one of Jesus.

Sitting at the kitchen table while Philip listens quietly, Ansu talks about how close she was to her only daughter. “She tells me everything,” she says, slipping into the present tense more than four years after Sneha’s disappearance. “She can go on in detail. That’s one of the things I really love about her.” Ansu spent the Friday night before September 11 visiting Sneha in the city. They ate Chinese food, walked around Battery Park, and watched Portrait of a Lady on video. When Ansu left the next morning, Sneha said to her, “Mom, can we do this more often?”

The family has finally stopped looking for clues to Sneha’s whereabouts. “I don’t have even a grain of hope that she’s alive or that anything else happened to her,” Ansu says. “It’s more peaceful for me to think she died in the World Trade Center than … I cannot bear to think that somebody killed her.”

What they’re looking for now is official recognition, if not proof, of what they’ve come to believe. Or, as Ansu calls it, “closure,” a word the family repeats like a mantra. “There is no final closure for me,” says Philip, breaking his silence in frustration. “She cannot just disappear in the air. There should be a body, an accident report, there should be something. How can they say she died on the 10th?”

Although they’ve been counseled that the odds are exceedingly slim, they intend to appeal Judge Roth’s death-certificate decision. It’s not about money, Ansu says; with the Victim Compensation Fund closed, Ron’s claim is worthless no matter what the decision. It’s about getting Sneha’s name added to the coming memorial. It’s about proving wrong the insinuations that alcohol and adultery might have led to her death.

“They’re trying to fabricate a picture,” says Ansu, “making Sneha look so bad. It looks like she’s some kind of confused, mixed-up, horrible person. She’s far from it. So kind, compassionate, beautiful inside, beautiful outside.”

If the mystery is to be solved, it will likely be through DNA evidence. As recently as a few months ago, it appeared that the city would not be able to identify any additional victims via DNA. But a recent advance in forensic technology—the use of a reagent that helps retrieve a higher percentage of purified DNA from bone fragments—has convinced city officials to send samples of the 9,069 still-unidentified remains back to a laboratory in Virginia for a new round of testing. In January, the process made its first 9/11 identification.

Sneha’s family, however, has pinned its hopes on her jewelry: her wedding band, engagement ring, diamond earrings, and the minnu she always wore. The melting point of diamonds is more than four times higher than that of bone, which turns to ash in just a few hours at 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit. A body trapped in the depths of ground zero (where the fires burned at 2,000 degrees) would leave virtually nothing behind, but a diamond could survive essentially unscathed. The city property clerk has recovered 1,350 pieces of jewelry from the ruins, only about two thirds of which have been returned to victims’ families. For the Philips, the remaining jewelry represents more than 400 chances to prove that Sneha was a hero.

They cling to a reply from the property clerk’s office like a life preserver. It says that they may have Sneha’s jewelry and requests photographs for confirmation. “When I got the letter,” Ansu says. “I was just so, like, hopeful that there was something.”

But, more than a year after she and Philip sent the clerk photos of Sneha’s jewelry, they have received no answer and have become increasingly frustrated by the delay. When I called to find out the status of the match, a spokesperson for the property clerk’s office said that the letter the Philips received was essentially meaningless. “If you sent in a letter about a plain piece of jewelry, a Timex watch, if there was one of them, we sent you back a letter that there’s a possibility,” he told me. “We had no idea if there could even be a match. But everybody got those letters.”

I ask Ansu what she would do if, hypothetically speaking, they didn’t find a match to Sneha’s jewelry. “I’d be very disappointed,” she says. “I know in my mind, part of her is in the ashes. There’s some kind of peace in that.”

I didn’t have the heart to tell her.