*Campers’ names have been changed.

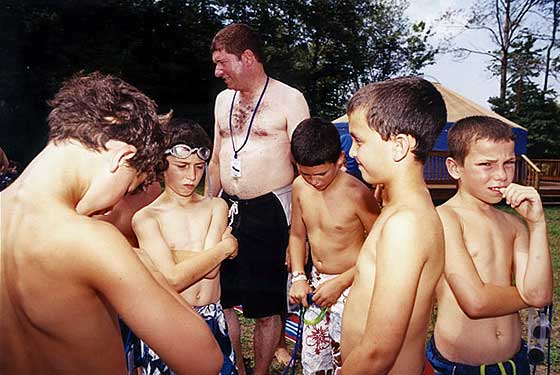

It’s 9 P.M., and I’m in the cookies-and-milk line with 350 other campers. Or at least I think it’s the cookies-and-milk line. If there’s a line at Camp Echo, I get in it. Two campers, Blake and Randy*, and their counselor, Mike, stand in line in front of me, and they’re not moving to my satisfaction. “Line’s moving slow, huh?” I say, glancing at my watch, but they just look at me. I guess type-A personalities don’t belong in the cookies-and-milk line. Finally, I get my tiny carton and my oatmeal-raisin, and join my 10-year-old bunkmates from cabin B5-2. They’re gathered on the deck of the “Nest,” a fifties-style diner, what I would have called the Canteen back in my first go-round as a camper more than 40 years ago.

About twenty campers of various ages crowd a Ping-Pong table like grown-ups around a blackjack table.

“Let Robin play,” one of my bunkmates shouts at a player.

“No,” the boy says. “I’ve been waiting.”

Yeah, buddy, I’m thinking. Scram. This is my game.

My counselor, Snoopy, comes by. Young enough to be my son, he stands a head shorter than me but is three times as muscular. “My real name’s Craig,” he told me yesterday, “but the people here can’t pronounce my name. They call me ‘Creg,’ so I’d rather they just call me Snoopy.” He’s from Birmingham, England, and this is his third stint at Camp Echo, where I’ve arranged to return for a Summer Camp Do-Over of sorts. The camp, over 80 years old, is located near Merrick, on Long Island, about an hour from Manhattan, and draws largely from the five boroughs, Long Island, New Jersey, and Connecticut. It’s only my second day here, and I’m infatuated with Snoopy in the way that 10-year-old boys get infatuated with their counselors. The problem is that I’m not 10. I’m 48, married, the father of three girls, a college professor. Infatuated with my counselor.

What I’m experiencing is “regressive pull,” a concept I’d never heard of until it was explained to me by Marla Coleman, the camp director and owner. Usually, it’s a bad thing, the tendency of a counselor to start acting like a child around a bunk of children. “With you,” she says, “we’re seeing its positive benefits.” I take this in with the force of revelation—it’s what brought me in the first place to Camp Echo after 30 years away, I think, and it explains why I’m so invested suddenly in cookies, milk, and Ping-Pong.

As a kid, I was a failed camper, an unimpressive physical specimen, an almost-sissy who had to use his brains to deflect the bully’s animus and divert his attention: “Psst, I’m not the one you want. There’s a sissy over there.” At Atlantic Beach Day Camp when I was 8, I organized a pickpocket ring in lieu of swim time. A year later, I learned to dog-paddle at Camp Catawba in North Carolina when an older camper shoved me into the pool in the deep end at night and then ran away. I never learned how to do the crawl, a source of shame my entire life.

Thirty years ago, I was an even bigger disappointment as a counselor at Camp Echo. The camp administration threw me into a bunk of the brattiest 10-year-olds anyone could imagine: privileged, whiny, spoiled—me when I was their age, but much worse. I remember the kids in my bunk placing bets on how long it would take to get rid of me. They liked the other counselor in the cabin; his name was Joel, and he listened without protest as they guessed whether I’d last one day, two, or a week at most. I was their third substitute counselor two weeks into the summer, and I had no idea how to handle the kids who flatly refused to obey me regardless of any consequences I offered. When I complained to one of the senior staffers, he’d poke his head in my cabin, do a General George Patton impression for a minute or two while the kids looked at him beatifically, and then he’d say, “See, you just have to be firm, Robin,” and then he’d close the door and the barbarians would riot again.

One day, the head counselor told me to get my subordinates to swim no matter what, but one kid refused to go. Nowadays, counselors learn positive techniques to handle such situations. But I had no models other than regressive pull, even if I didn’t know what it was at the time. So that’s what I did. I pulled. I pulled him off his bed and led him down the stairs of cabin B5-2, and then he dropped to the ground limp and expressionless, so I pulled some more. I dragged him about ten feet toward the lake when the head counselor marched up to me and said if he ever saw me lay a hand on a kid again, he’d fire me. The kid looked up at me with a smile, snapped his fingers, and pointed in “Gotcha!” fashion.

I quit on the spot and mentioned the incident to no one for 30 years.

Admittedly, my reasons for wanting to go back were a bit regressive. I wanted to use my unfair advantage as a fortysomething male to make a big impression on a bunk of 10-year-olds. I wanted to observe the cruel society of boys and relearn the lessons of cutthroat male competition. I wanted to beat them at swimming, baseball, table tennis, capture the flag. Pathetic? Undoubtedly.

I don’t like to think I hold grudges, but I do. I had a grudge against childhood. I had a grudge against that particular child who had bested me 30 years ago. He and his bunkmates haunted me, all of those Hobbesian boys (nasty, brutish, and short) who resided in B5-2 in 1976. I don’t know what I thought would happen when I returned. Those children are 40 years old now and long gone. I guess I hadn’t moved on. Perhaps if I’d learned better lessons as a camper, I’d have made a better counselor. Perhaps if I’d been a better counselor, I might have made a healthier adult, not the kind who wants to pay back 10-year-olds.

My first hints of the dramatic changes since I’d left Camp Echo were the water fountains scattered strategically around the 200 acres. I certainly don’t remember those, but I’m grateful, especially as the camp is suffering through a 100-plus-degree heat wave. At dinner, campers line up without stigma or comment to get meds. That’s new, too. In fact, everything seems new, from the water park on the lake to the GaGa court (GaGa, Marla explains, is a “gentleman’s version of dodgeball”) to the attitudes of the administration. Marla, a past president of the American Camp Association, bought Camp Echo with her family five years ago and runs it like a cross between a small, enlightened European principality, say, Liechtenstein, and a cruise ship.

If Camp Echo were its own country—it has its own flag, raised and lowered with the U.S. flag every day—Marla would be the country’s information minister. She tells me that camps have only recently learned what business they’re in: “They used to think they were in the recreation business,” she says, “but they’re really in the youth-development business.” Like so many institutions of contemporary childhood, camps now serve an educative agenda, and this one has a moral code as well. There are ten Camp Echo Values, posted inside each bunk, reinforced every day by counselors and staff, culminating in a Sunday-night torch ceremony in praise of individual campers who have exemplified one of these virtues during the past week. Marla has given me my own laminated sheet of Values:

SELF-RELIANCE

COURAGE

PATIENCE

COOPERATION

COMMITMENT

RELIABILITY

COMPASSION

REASON

CREATIVITY

SELF-IMPROVEMENT

(There were no Echo Values when I was here last. But in hindsight, they might have looked like this:

INTIMIDATION

HUMILIATION

CRUELTY

BOREDOM

IMMATURITY

SADISM

INDIFFERENCE

EMBARRASSMENT

SELF-PRESERVATION

TOUGH LUCK)

Not only has camp changed, but kids seem to have changed, too. No one paid attention to kids when I was one—not parents, not teachers, not counselors. Childhood was something you went off and did on your own until you got over it. I remember a kid in fifth grade. We called him Booger. He’d make little bombing noises throughout class. Once, he peed out the bathroom window on kids playing kickball. Another time, he grabbed our teacher, Miss Cotton, and pulled her across her desk. Booger was either being yelled at by the principal, ridiculed by the other kids, or manhandled by a teacher or two. Today, Booger would be medicated and in therapy. Maybe me too.

What I remember most from sleepaway summers are the torturers of little animals. When I was 9 at Camp Catawba, a group of wayward boys threw a knife at a stunned bullfrog in the middle of the main path while counselors walked by unmoved. With each successive toss the dagger edged closer and closer, until one camper stuck the blade into the bullfrog’s back, and its heart seemed to jump out of its mouth. That was camp play. That was praiseworthy.

Praise has almost reached pandemic levels at Camp Echo. The campers even praise one another, which just seems sick. On my first day, Tony, a slightly chunky kid who would have been beaten up for his chunkiness in my day, invites me to play catch with him at Twilight. Like everything else here, Twilight is scheduled, a certain time of the day when the boys (and the girls on the other side of the lake) are free to play within an appointed and supervised perimeter, called the Twilight Zone. We toss a rubber ball and a hardball, and Tony keeps praising me for my throws and my catches, most of which are off the mark—and I’m wondering, What kind of boy is this? This must be a new version, introduced during the eighties or nineties after my version of boy was phased out.

At dinner, another boy turns to me and puts his finger to his nose. “If you see this,” he says, “do it, too.”

Presently, Snoopy puts his finger on his nose and I put my finger on my nose and so does everyone else, until one lone camper remains who hasn’t yet put his finger on his nose.

“You! You! You!” they chant at him, and he smiles broadly, and I’m thinking, You what? You nincompoop? You idiot? You blind fool who can’t put his finger on his nose fast enough? Is that all? Don’t these kids even know how to humiliate each other properly?

The bunk leader, according to Snoopy, is a boy named Jason. This is the kid I would have been terrified of when I was 10—he has the haircut and the look of a little Roman centurion. “Yessss! We have cooking today!” he yells one morning when Snoopy tells us the day’s schedule. I like cooking, too, but I never would have admitted it within earshot of a centurion boy when I was 10.

What’s going on with these boys?Of course I’m envious. I want their childhoods. In my day, positive reinforcement hadn’t been invented yet.

“Sounds delicious!” says Gary, a new kid like me, with a sweet voice, who would have been beaten up twice, once for being a new kid and once for having a sweet voice.

The bunk comedian, Dale, has blond hair and a mischievous grin. He sometimes wears a top hat around the bunk (he might have wound up in a body cast for that alone). “You just missed Top Hat and Tiara Day,” he tells me.

“I think it’s time you and I had a heart-to-heart,” he whispers on Luau Day morning while we’re sitting on the cabin porch waiting for Snoopy or our other counselor, Brad, to take us to breakfast on the beach of Camp Echo’s spring-fed lake.

“Why?” I ask, thinking he’s going to critique my yellow luau shirt, when he bursts into a song from The Lion King.

On the way to lunch one day, a darkly tanned boy named Vince who wears a turned-around Yankees cap runs after chunky Tony, saying he’s going to kill him. I should point out here that while I’m not in favor of Vince killing Tony, at least Vince seems more like the kind of boy I’m used to. He pulls Tony to the ground and sits on him. At this point, Tony is laughing.

“Do something, Robin,” he begs.

“Sorry, I’m just a camper,” I say, wondering if I too should sit on Tony just to prove it.

“Boy, I wish you were a counselor right now,” Tony says.

Vince lets Tony off the ground and starts kicking him in the butt as Tony walks with me. “Come on, Vince,” I say, but Vince ignores me and starts beating Tony in the face with a palm frond left over from Luau Day. Tony covers his eyes and starts crying. I ask if he’s okay, and Vince is concerned as well. Once Vince determines that Tony is going to be fine, he starts kicking him in the butt again.

Normally, as a grown-up, I would have stopped this before now, but regressive pull has me in a headlock, and Vince and Tony have accepted that I have no authority here. So have I. Later, I ask Tony if he’s okay. “Sure,” he says with a big grin. “Vince and I always fool around like that. We’re friends.”

What’s going on with these boys? Of course I’m envious. I want their childhoods, their camp experiences. Even though kids lately are often portrayed as hyperparented, heavily medicated, and overscheduled, the boys of cabin B5-2 seem a lot better off than my generation was.

Somehow, I grew up more or less well adjusted, though I’m not sure how. I didn’t have anyone helping me along like these kids seem to have. To me, childhood implies threat and alienation. My dad died of a heart attack when I was 7. My mother had to go back to school and work, and I spent most of my days unsupervised. Positive reinforcement hadn’t been invented yet. I remember my great-uncle worrying in front of me that I was a sissy. My mother told me girls wouldn’t like me if I didn’t gain weight. Family, schools, and camp worked hand in hand to turn us into little arts-and-crafts basket cases.

Certain things haven’t changed about camp, at least for me. I sputter and gulp my way through the crawl test, barely earning the blue plastic bracelet that serves as my ticket to the deep end. I still can’t shoot a basket. My four-foot-five compadres consistently outscore me.

The food hasn’t changed. Spaghetti and meatballs, chicken potpie, grilled cheese and curly fries, chicken tenders and, one day, their opposite. Chicken toughs, I call them: chicken breasts of a variegated southwestern adobe color. Pitchers of water and high-fructose colored juice sit at either end of the table. If campers don’t want to finish their juice or water, they simply pour it back into the pitcher. For this reason, I try to grab water as soon as I sit down. Green juice that tastes like gummy-bear blood and backwash is not my idea of refreshment.

The bunks haven’t changed either. There’s no A/C, and that bunk smell of old towels and sweat pervades the cabin, intensified by the heat wave. Lights out at ten, though Brad usually allows us “flashlight time” for the duration of one cut from a Red Hot Chili Peppers CD. I bunk above Gary, the other new kid, in a coffin-size compartment that barely contains me, and I can hardly nod off in the heat. During morning cleanup, each bunk competes with the others for a sundae party at the end of the week, but nobody in B5-2 is too interested. I’ve arrived on Visiting Day, and the parents have left behind a Willy Wonka portion of sugar-coated love and expiation for their campers. I have no candy because my parents are dead and I’m a new kid, but my bunkmates display compassion (Value No. 7) by offering me some of theirs.

The regimentation of camp hasn’t changed much either—if anything, it’s become worse. Information Minister Marla will tell you that camp is a family, but it’s really a kingdom, a feudal society that demands complete obeisance. My immediate group has been told that I’m to be treated like any other camper. A lot of the other campers seem baffled by me—one wondered how many grades I was held back—but my counselors have no trouble addressing me like a 10-year-old. I’m reminded of this one morning as I go to fill my water bottle from the fountain next to B5-1, the cabin beside ours. Vince with his turned-around Yankees cap tells me there’s a better fountain, with colder water, behind our row of cabins, so I start making my way over.

“Robin, where are you going?” demands 18-year-old Brad, who’s sitting on the porch regarding me cannily.

“Come on, Vince,” I say, but Vince ignores me and starts beating Tony in the face with the palm frond.

“I—” I start to say and point.

“Is it necessary for you to go to that water fountain?” he asks in his best counselor voice, friendly but firm.

I put my head down, Charlie Brown–like, and trudge back to the lukewarm water in front of B5-1.

Another time, while running relays with coconuts during Luau Day, I suddenly get a terrible headache and tell Brad I’m going back to the bunk to get some aspirin. “We’re going to have to have a consult about that,” he says, and crooks his finger for me to step aside with him. He tells me that I’m not allowed to have any medicine in the bunk and that as a camper I can’t go to the bunk alone, so he recruits a 16-year-old counselor-in-training to escort me.

Most of the time I like this place, and I find myself reliving camp in unexpected ways. It’s impossible for me to be the jerk I had hoped to be, but I’m not a sissy either. I’ve tried on a new kind of boyhood, XL, and it fits. I’ve gone mountain biking, kayaking, horseback riding, swimming, played GaGa (where I struck out two counselors in a row), run basketball drills, and golfed, which I hadn’t done since I was 8, when the great-uncle who questioned my masculinity took me out on a course and criticized each swing.

One morning, I climb a 60-foot ladder to a tiny platform where I’m supposed to swing out onto a trapeze and fall on my back into a net below. Slowly I shimmy up to the platform, despite a fear of heights that at 60 feet does not feel unreasonable. A staffer tells me to rub my hands in a chalk bag so I can hold onto the trapeze, but when I actually grab the bar and feel its heft, I’m overwhelmed by a sudden panic, despite the rope harness I’m wearing. “I don’t think I can do this,” I whimper. “I want to get down.”

My bunkmates and counselors stand below, shouting for me to press on. And then all of a sudden I’m in mid-air, swinging.

“On the count of three, I want you to kick up your legs and let go of the bar,” the instructor says, and counts one … two … three, and I’m still swinging from the bar. This time, he says, he wants me to pay attention to the letting-go part.

And I do.