The hedge-fund guy is the ultimate shopper, says Ty Wenger, editor of Trader Monthly, because he “made his millions by knowing what to buy, and by knowing exactly how much things should cost. He has a keen sense of worth.” Which is not to say that it’s the same as yours. Here’s how his spending behavior is perceived around town:

Everybody needs a place to live…

Anyone who’s lived in New York longer than five minutes understands what hedge-funders have done to the real-estate market. Until five years ago, nobody would’ve dreamed of paying $20 million for any apartment. Now, it happens so often nobody even talks about it. There’s also the downtown migration: A classic six on Park Avenue is a nice place for Grandma, maybe, but it’s a lousy place to hang art. For that, you need 5,000 square feet in Tribeca.

And something rare and expensive to put on their walls …

Along with Russian oligarchs and Chinese billionaires, “hedge-fund guys” are cited whenever people try to explain the current art-market madness. The most prominent of them is SAC Capital’s Steven Cohen, owner of Damien Hirst’s shark—for which he paid either $8 million or $12 million, depending on whom you believe—and the would-be buyer, at $139 million, of the Picasso through which its owner, Steve Wynn, put his elbow. Whereas hedge-funders keep much of their day job secret, they often prefer high-profile art acquisitions, because they can boost value—that of the particular work and its artist, certainly, and possibly that of other artists in their portfolio. As Amy Cappellazzo of Christie’s pointed out during Art Basel Miami Beach, there’s a “permission-giving” quality to a deal like Citadel’s Ken Griffin’s paying $80 million for a Jasper Johns, almost five times the artist’s auction record. It creates a new context that makes it seem utterly reasonable to pay $8 million for, say, a Basquiat. “The big fear,” says one art consultant who has several hedge-fund clients, “is that if the market turns, they’ll get out of art just as fast as they came in.”

While preferring not to be seen as a completely selfish bastard…

When you’ve got one guy (George Soros) doling out $4 billion, hedge-funders know they can compete in philanthropy only in terms of quality, not quantity. They gravitate to where they can have the biggest impact: kids and poverty issues. The Robin Hood Foundation, founded by Paul Tudor Jones, has devoted more than $500 million to causes centered on children and education. Traditional cultural institutions have done less well with the youngish hedge-fund crowd, but that is changing as the industry matures and the institutions themselves make a greater effort to target this new pot of wealth. Alma maters, too, are poised for a payday as Harvard (or Bucknell) looms on the horizon for all those little hedge-fund offspring.

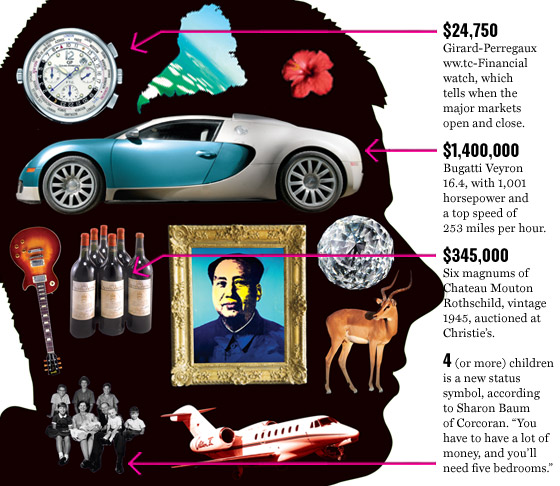

Even if they drive a pretty sweet car…

An enterprising reporter for the Hartford Courant recently catalogued the 66,000 cars owned and registered by the 61,972 residents of Greenwich. Mercedeses and BMWs account for one of every ten cars; surprisingly, there were slightly fewer than 1,000 Porsches, a mere 94 Ferraris, and (can you believe it?) just a single, lonely Lamborghini. One make that did not make the list: the Bugatti Veyron 16.4, which has 1,001 horsepower and sells for $1.4 million. Which means it may still be possible to be the first in Greenwich to own one.

And have lots of other great stuff…

Merchants offer their testimonials:

WATCHES: You buy a watch today and you can instantly sell it in any capital market in the world. It’s a toy that gives them prestige in their social circles, like a car would. But you can’t bring a car into the office.

—Edward Faber, CEO, Aaron Faber

SHOES: The fact that someone who’s 26 can afford to buy five pairs of our shoes kind of tips you off. And the quest for individuality: They want something a little different from what everyone else has. The Wolfe loafers are popular, which have the cross-bone hardware on front. They shop alone, which is also a little bit weird.

—Derrick Miller, creative director, Barker Black

BOATS: The hedge-fund people are buying 60-foot, 70-foot boats. For a 60-footer, $2.3 million. Some even put an office inside their boat, TVs switched onto Bloomberg, all Ethernet connected, satellite TV, GPS radars, all of it. And they like Jacuzzis a lot. I had one guy pick me up in his baby Boeing 707 and fly me over to the factory in England to see his boat. There was this one gentleman, when he put his feet up on the table, his toes were just in the way of the TV, so he asked us to reposition the TV. They really expect the best.

—John Novak, manager, Sunseeker

WINE: They drink the blue-chip burgundies like BRC or Roumier. If they order white, it’s Montrachet. One guy preordered Montrachet Domaine Ramonet 1978, the first year of the greatest vineyard from one of the great winemakers in the world. That’s $4,850.

—Robert Bohr, wine director and sommelier, CRU

JEWELRY: They don’t have so much time to shop. To keep these clients, we have to make their lives as easy as possible. Sales associates have to work with them via e-mail. They are very nice. I don’t think you can compare them to children, but they are a little like children. They’re so excited, and they buy like it’s a new toy.

—Nicolas Luchsinger, director, Van Cleef and Arpels

TRAVEL: There’s a lot of hand-holding. We had one customer who was interested in playing squash in London. Not only did we have to find a private squash club but a player who was ranked on this side of the Atlantic so that he could have a competitive game. And we had to do it between meetings. Our concierge service jumped through hoops to get it done, but his meeting ended up running late and he had to cancel.

—Paul Metselaar, CEO, Ovation Travel

… But yes, Virginia, there are tightwads who work for hedge funds.

Justin Evans walks to work every day from his home near Central Park. He never takes a taxi, because he wants to save the $8. For lunch, he eats $6 sandwiches from the deli. “I’m a value investor, even to the point of how I live my life,” he says. “I consistently try to convince my wife that we are poor.” The top 1 percent of any industry makes “obscene amounts of money,” Evans says. But most of the guys he knows are the “cheapest guys you’ll ever meet. It’s the ones who’ve drunk the Kool-Aid and think this will last forever, who spend money on watches and cars and other things to impress the girl who wouldn’t date him in high school. It’s a giant poker game, and they’re all passing around the same pile of chips. When the music stops, there won’t be enough chips for everyone.”

Additional reporting by Wren Abbott, Miriam Datskovsky, Jonah Green, Kira Peikof, Denise Penny, and Marc Spiegler.