For a split second it seemed as if the man might live. For one boozy, demented moment, time started to bend and warp, and everyone by the freight elevator—all the waitresses and coat-check girls and bartenders and friends, all those of age to drink and all those barely under, the few people involved in the fracas and the several looking on from afar, as well as floor manager Granville Adams, an actor in the HBO show Oz, who had never intended to throw a man to his death—all of them had the shadow of a chance to consider just how wrong everything had gone. And then Orlando Valle dropped.

The Harlem-bred mailroom worker had come to B.E.D. a week ago Friday to celebrate his 35th birthday. There, he did what was the thing to do among the elite of New York three years ago, what many of them now pretend they never tried: drink overpriced vodka out of a “private” bottle. He had chosen B.E.D. as the site of his libation, perhaps attracted by the notion of lounging on a mattress, his feet warmed by complimentary booties—even though the beds were worn and ripped, the site of numerous late-night conquests and frustrations—or perhaps attracted by a cocktail menu with names like “The Pussy Galore” and “Heavy Petting.” Now, after a fight over a girl, he was falling down the elevator shaft.

As he moaned from four floors down—his body disfigured, his blood dripping onto the elevator cab he had landed on—languishing with him was an entire city block. As a hot zone of New York nightlife, West 27th Street between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues had an astonishingly fast rise and fall: five years, in all, from the beginning to the beginning of the end. During that time, the street attracted Bono, Paris Hilton, prostitutes, drug dealers, and everyone in between—thousands of people on a single block. Together, they represented, for better or worse, the personality of New York at the beginning of the new millennium. But when Valle died of his head wounds Saturday morning at St. Vincent’s hospital, the life went out of the party.

The block, in 2000, looked typical of Outer Chelsea, a neighborhood of leather bars and chop shops that Realtors called OuCh. It featured a scrap yard, a valve-repair center, and an auto-detailing shop. At night, transvestites paraded through, attracting curious motorists who rolled down their windows and filled the air with innuendo. Clubbers scampered arm-in-arm to Twilo, the megaclub at 530 West 27th. “It was freaks and crackheads,” recalls one clubber, Melissa Maron. “You never knew what was going to come out of the corners or from behind a pile of trash.”

But the street held one major advantage for club owners: The city had zoned it for commercial use, making it easy to receive a liquor license. At the turn of the millennium, as the Giuliani administration cracked down on rogue club owners, many of the rest decided to go west. The trendsetter was Amy Sacco, the owner of Lot 61, who had lived for four years in a raw loft near Twilo at 544 West 27th. Having brought the space up to code, even adding a hot tub, she finally tired of a long-running battle with an ornery landlord, who filled the locks with glue in his attempts to frustrate his residential tenants. Sacco moved off the street, but on the opposite side, just up the block, she rented a small space at 515 West 27th. Bungalow 8 opened in the spring of 2001.

Conceived at the height of the dot-com boom, Bungalow 8—like Studio 54 in the seventies—defined the glamour of a decade. Tall, voluptuous, and platinum blonde, Sacco became a Texas Guinan for the US Weekly era, famous for her style sense, her mood swings, her tight door policy. She had made hundreds if not thousands of best friends since arriving from New Jersey, especially among the wealthy, but only a few of them were admitted into her tiny room of 125 people. Having money was the easy part. Those who made it inside generally had made it outside. They were famous or beautiful or interesting. And the few who held a Bungalow membership card carried with them Amy’s personal endorsement.

Sacco allowed no one to take pictures inside Bungalow 8. Because people felt safe, they mixed, often indulged freely in excess, and rarely dropped tales of their exploits to the press. For “Amy’s friends,” the place felt like a small-town bar on a good night. The doormen, Disco and Armin, protected their customers. If George Clooney, leaving the club in a buoyant mood, happened to pass a pretty blonde from the Upper East Side, grab her by the hand, and jokingly drag her off to his Town Car, Disco would be there to break them apart with a karate chop and a soft, smiling admonition: “Not for you, George.” The girl’s boyfriend would yell, “Yeah, beat it, Clooney!” and everyone would get a little charge out of that—Clooney most of all; for once, he felt like a regular guy.

An anachronism of Sacco’s was her refusal to monetize her milieu, but two of Sacco’s younger friends had no such qualms. Celebrity, in New York, was changing. The first to make the most of it were Noah Tepperberg, a balding, gravel-voiced Stuyvesant graduate, and Jason Strauss, his boyhood friend from Riverdale. Still in their twenties, they dreamed of creating an exclusive club like Sacco’s but on a vast and far more profitable scale. They would manage that feat by systematizing what might be called the club cascade effect: Celebrities attract models, models attract businessmen, and businessmen bring dollars.

The financial basis for this dream already was in place in the form of a high-profit sales technique developed by David Sarner, an owner of Soho’s ever-crowded Spy Bar. In 1995, Sarner realized he had more customers than his bartenders could handle. So Sarner brought the bar straight to the tables. He delivered vodka, mixers, ice, and glassware and allowed customers to pour their own cocktails. The next year, at Chaos, Sarner and his partner Michael Ault made bottle service mandatory—if you wanted to sit at your own table. Buying a bottle became a badge of status, and nightclub owners found a brand-new profit center.

Tepperberg and Strauss implemented bottle service on an industrial scale. In an abandoned taxi garage on the southwest corner of 27th Street and Tenth Avenue, just a few hundred feet from Bungalow 8, they created Marquee. The centerpiece of their $2.5 million renovation was a gleaming Philip Johnson staircase. “If a pretty girl comes from the top of the stairs all the way down, the whole crowd can watch,” says the club’s designer, the former Life director Steven Lewis. “If a celebrity walks up the stairs, people see them going up. That was not done by accident. It was all on purpose. The idea is to see people.”

Many of the celebrities spied on the staircase were there for business reasons. Marquee’s “special sauce,” as Tepperberg calls it, was a separate marketing company, Strategic Group, which placed the young club owners in the center of a burgeoning celebrity-industrial complex. Strategic connected Tepperberg and Strauss with companies that wanted to reach influencers and trendsetters by bankrolling parties inside Marquee. Motivated by the chance to appear in the gossip pages, celebrities arrived to host events. Models of all kinds—runway girls, commercial girls, faces, legs, pretty young things from West Virginia—came to cozy up to celebrities. Bankrolling it all were the “bottles”: the term of art for businessmen who plunk down $400 for $40 worth of vodka.

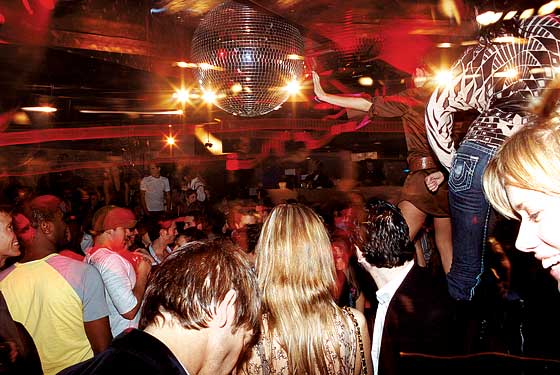

So many people packed Marquee in its first year, 2004, that the crowd of cars and people often blocked several lanes of traffic on Tenth Avenue. Inside, a parade of celebrities canoodled, guest D.J.’d, or threw premiere parties—a vast boldface honor roll recently trumpeted on the occasion of Marquee’s third anniversary and mocked by the Website Gawker under the headline WE CANNOT DEDICATE, WE CANNOT CONSECRATE, WE CANNOT HALLOW THIS GROUND.

It wasn’t Gettysburg, but the dance floor at Marquee sparked a phenomenon: the most concentrated and expensive burst of club development in the history of New York. So many nearby spaces came up for rent that the real-estate broker Steven Kamali would park his car on the street and spend all day marching club owners through their options. “It was like the gold rush,” he recalls. Cain arrived, then B.E.D., then Home, Guest House, Pre:Post, Pink Elephant. “They weren’t saying no to anybody,” Sacco recalls. “If you had a bank account and a heartbeat, you could get a place.”

Twenty-seventh Street became club row, a one-stop party shop. For a moment, it was magical—like an amusement park for adults. Instead of taxiing from one neighborhood to the next, clubbers could flit across the street. Marquee was the “Page Six” spectacle. On quieter nights, when a vacation vibe seemed best, one would start on the opposite end of the street, under the game-lodge tent of Cain. Bungalow 8 was for late nights, and in the middle of the block, one could mix it up with the mainstream.

Except for Bungalow, all the clubs had one thing in common: bottle girls, women in short skirts who ferried over ice and spirits in exchange for plastic. Nightclubs were big business now. If you carried a black AmEx card, you could count on getting in, somewhere. “Bottle service—it was a killer,” one club worker recalls. “Because now you didn’t have to look right to get in. The owners didn’t care about the quality of the crowd. The bottom line was the money. It was, Sell those tables, sell those tables, up-sell, magnums, bottle minimums. And you now had—forgive me for saying it—every undesirable seated in a nightclub.”

If the undesirables had a king, it would have to be Jon B, the owner of Home and Guest House. He is slumped in the front seat of a black GMC Yukon, his five-foot-seven-inch frame barely visible behind tinted windows and a black goatee. He is freshly shaved, with a few red nicks to prove it, and clothed in a black suit, a black tie emblazoned with a red D&G logo, and square-toed shoes, one of which presses heavily on the accelerator. I first met Jon B three months ago, and today’s excursion happened before the death of Orlando Valle at B.E.D. We are headed east on the L.I.E. to observe Shabbat at the home of his aunt and uncle, Orthodox Jews in Roslyn. It would be best to arrive before sundown.

Jon B appears a bit miffed. He has just learned that Amy Sacco, the queen bee of New York nightlife, blames him for the downfall of the block she pioneered. I’ve told him about having had tea at the Royalton with Sacco, who had glided in wearing rabbit-lined Tracey Ross mukluks, her face cloaked by a vintage fedora, and proceeded to hint and flirt but never quite state that she might sell her club. When I brought up Jon B, her scratchy voice hardened and rose a note. “I refuse any comments about that person,” she said, leaning into my digital recorder. “He brought it to a grinding halt, as far as I’m concerned. That’s all I’m going to say. He ruined the block.”

It’s a disheartening thing for Jon B to hear, especially since he worked for Sacco for several years—promoting her profitable Friday party at Lot 61. Friday night was Sacco’s bread and butter, generating three times the revenue of her glamorous Monday nights, when the young promoter Richie Akiva presided over New York’s toughest door. Akiva was the one who enforced the rules of the game, generating the buzz that helped Sacco establish her crowd and her reputation. But it was Jon B who paid the bills. Asked what happened between them, Sacco had texted back the ultimate put-down: “Um, I don’t remember?”

Jon B hoped to attract “The B-plus people.” He was the king of the undesirables.

The comment wriggles about Jon B’s mind, elevating in importance until it rises to the status of a symbol for all that is wrong with the business, in his mind anyway: the inability of club owners to realize their common interests and stand together. “Why would she say that?” he says. “Why would she say that? Does she really not remember? Some people care about the truth and some people—whatever.” He is one of the most successful men in the industry, yet he has not won acceptance from the clique of twenty or so people who rule nightlife in New York.

We arrive at a small house on Lord’s Lane in Roslyn, where I quickly receive a yarmulke emblazoned with the name of a boy bar mitzvahed long ago and a warm greeting from Jon’s hefty aunt Aviva. The mother of eight children, Aviva joined Jon’s family—the B is for Bakhshi; they are from Iran—by marrying his uncle Farzad, a gynecologist who goes about every motion, even slicing a jelly doughnut, with an air of total commitment. Jon’s family arrives: his short, curly-haired father, Glen; his mother, blonde Juliet; and his uncle Jeffrey, a fair-skinned district attorney from Oyster Bay, who confesses to a hearty appetite for cupcakes. There is a table, draped in two layers of protective plastic, groaning with food. The candles glisten.

Dinner, a four-hour affair, begins with Fresca and sparkling pink wine and chickpea balls—the Iranian answer to matzo—and continues through several Torah readings and lessons and an ardent speech by Jon’s cousin Daniel. Finally, Jon’s aunt Jacqueline scrapes the chicken bones off the plates and the conversation meanders toward Jon’s area of business.

Here, in this circle of devout souls, the irony is not lost upon the group that their son has become wealthy by entering an irreligious profession. Glen and Juliet say they’ve visited their son’s clubs only once, parking on the street just outside. Upon leaving, the couple discovered their car had been towed to the pound at 38th Street. Juliet, laughing, recounts the story without mentioning the obvious fact that the same thing had happened to Jennifer Moore, the 18-year-old New Jersey high-school graduate who was murdered after partying at Guest House. Later, we discuss Tara Conner, Miss USA, who spent some late nights at Home before Donald Trump packed her off to drug rehab. “What were you doing, Jon? That’s your club!” Jeffrey laughs. “She wasn’t even 21!”

By the summer of 2005, New York nightlife had exploded into a $10 billion industry. The cascade effect continued to flow but in an unanticipated new direction. Celebrities were bringing models, models were bringing “bottles,” and the physical bottles, the ones containing alcohol, were attracting a new and even larger crowd from Brooklyn, the Bronx, Long Island, and New Jersey. Though unable to befriend Was, Marquee’s dapper, suited doorman, they were eager to drop $400 for that ultimate display of public status: a liter of Grey Goose. Greeting them at the door was Jon B.

If Marquee had monetized exclusivity by widening its parameters, Jon B sought to expand that business model even further. If Marquee looked beyond “Amy’s friends” to the A-list, Jon B hoped to attract—as he puts it today—“the B-plus people.” If Tepperberg and Strauss had shrunk down their dance floor in favor of more tables, at Jon B’s clubs there would be no dance floor—it was all tables. Jon B had a paradox planned: the most massive “exclusive” party of all time.

Home debuted in July, Guest House in August—both on the second floor of the Twilo building, which housed Spirit on the ground floor. The same summer, B.E.D., which had opened in January on the sixth floor, debuted its rooftop lounge. “That’s when all the bridge-and-tunnel guys came in,” a 27th Street veteran recalls. “These are the guys who brought the Jersey girls and the short shorts. They mobbed the whole street. And then, when you walked to Bungalow, you saw seven trashy blonde chicks standing outside begging to be let in, and guess what? It takes away from the atmosphere.”

Jon B liked his crowd, reasoning “they have money, and they want to have a good time.” It is said that he made $2 million last year by packing his clubs with the help of mass-market promoters, who typically take a cut of bar and table revenues. The owners of the events company Impulse would bring a hundred of their friends from Long Island on any given night. David Jaffee, an investment banker, would send out e-mail blasts beginning, “Greetings from my cubicle on Wall Street” to 75,000 people whom he encouraged to attend parties where he rarely deigned to appear.

Suddenly, the clubs filled with girls who did not look their age. Eager to provide eye candy for the men who bought the bottles, promoters hustled the girls inside the clubs in groups of ten or a dozen that the doormen never carded. All of the clubs had underage girls; some promoters specialized in bringing them. “You were able to bring certain girls no matter what age they were,” recalls a promoter who chaperoned some as young as 14. “If they’re a model, you bend the rules a little. But you have to make sure that she’s not going to be a staggering lush at the end of the night. These people are not the ones you’re going to find in a Dumpster the next day. They don’t take candy from strangers.”

Jon B’s clubs stay open more nights a week than the others—Guest House five, Home six—and therefore he had the most seats to fill. The word on the street was that Guest House was marketed to younger clubgoers and they brought along their underage friends. Jon B freely admits that he largely relied on promoters. “Think about it,” he says. “If you’re open six nights in one place and five nights in another place, you gotta fill it somehow.”

Jon B didn’t see underage girls, and he didn’t wish to see them. He didn’t smell marijuana fumes either. According to his own account, he didn’t visit his clubs more than a few times a week. Rival club owners up and down the block thought he could have maintained a better relationship with the police and spent more on security. “I was in there one night, and somebody started hassling me,” recalls David Sarner. “They were hitting on my wife and my friend’s girlfriend, and I asked the guy to move away from the table and it got very ugly. And I’m looking around to find a security guy to remove the guy because I didn’t want to get into a fistfight—and I’ll never go back again. They’re very understaffed there.” (Sarner would eventually move his meatpacking-district club, Pink Elephant, to 28th Street—and then tunnel under Crobar to get a door to the crowds on 27th.)

By the summer of 2006, the street crawled with people—forcing the police to barricade both ends. Masses of visored men in bright T-shirts stumbled through, smoking joints, carrying plastic cups, urinating on the walls. Thin girls toddled out in spike heels. It was a boozy Cancún North. People threw up in front of buildings and on their clothes; turned away at the door, they spat at the doormen. “We’d find people passed out in the bathroom,” recalls a former employee of B.E.D. “You would think it was a dead body. Passed out, like scary passed out, like smack them, pick them up, they’re like Jell-O, like someone took their spine out. And on the street. You would literally see people face down in the gutter.”

Inside the clubs, people started doing “bottle shots”—drinking straight from the bottle without using any kind of glass or mixer. Clubs quietly hired EMTs—which cost thousands of dollars each night—and the ambulance companies did a steady business. Men would find women passing out on the street, lift them onto their shoulders, and carry them off to a taxi. On Saturday nights, when Spirit hosted its hip-hop party, there were fights, frequent arrests, and men making suggestive comments to the women leaving Bungalow 8. Prostitutes and drug dealers walked down the street, freely propositioning anyone they met. “It started to feel self-destructive,” says one clubber, “a Disneyland for drunks.”

The most successful promoters were raking in thousands every night, some making half a million a year. There was undeclared income—free dinners, access to country clubs, trips to the Bahamas—and always more businessmen at the back of the line eager to be ushered inside. The promoters worked constantly. Some kept up the pace by feeding a habit. Bathroom lines were getting crowded, and people were coming out smiling, twitching, chattering. “I didn’t like that scene—it had gotten too crazy,” recalls one promoter who was easily making $100,000 a year. “It was ready to blow up.”

On the morning of July 25, Jon B was awakened by his ringing cell phone. Friends were calling to say he was on the news. An 18-year-old girl named Jennifer Moore had gone missing after a night of drinking in West Chelsea, where she had cocktails at Guest House. Mindful that many partyers drift from one club to the next, hardly knowing which one is which, Jon B thought the news was probably wrong. “I was like, ‘Naah, everyone’s probably just making a mistake,’ ” he recalls. “ ‘It’s probably not my place, it’s someone else’s place.’ ” He went back to bed, slept a few more hours, woke up, and turned on the TV. “When I turned on the news, I was shocked,” he says. “I started calling my lawyer and freaking out.”

The murder of Jennifer Moore has been described on 27th Street as a Lemony Snicket tale—a series of unfortunate events. Moore and her friend Talia Keenan were carded at the Guest House door that Monday night, but Moore flashed her sister’s I.D. After leaving the club, the two found their car had been towed. When they reached the tow pound on Twelfth Avenue near 38th Street, they were so drunk that the attendants wouldn’t give them their car. Keenan was so far gone that she passed out and an ambulance was called to take her to the hospital. Moore slipped away and was found several days later in a Weehawken Dumpster.

Moore’s killing might not have attracted so much attention had it not followed a similar murder, that of 24-year-old Imette St. Guillen, who had concluded a night out with a few drinks at the Falls on Lafayette Street and was later found near the Belt Parkway, her face wrapped in tape, her body covered with a floral-print comforter. A bouncer at the Falls named Darryl Littlejohn was charged with the John Jay graduate student’s murder—only three months before the indictment of another bouncer, Stephen Sakai of Opus 22, for shooting four people outside of that club, killing Gustavo Cuadros, a 25-year-old from Red Bank, New Jersey. All of it, taken together, added up to hot copy.

Inside the New York Post office on Sixth Avenue, Sunday editor Lauren Ramsby commanded her reporters to bring her any news they could find about underage drinkers on 27th Street. It wasn’t hard: They were parading down the block in belly-baring tank tops, yelling about how many Jäger bombs they had downed. According to one Post reporter, Ramsby wanted “to blow the lid open” on the underage-drinking scene. “It’s the perfect story,” another Post reporter says. “It’s linked to a murder. You have the villain: club owners. They’re giving alcohol to underage girls. And then you have law enforcement falling down on the job. You have the city-bureaucracy aspect, you have the commerce aspect, you have the stricken family losing their child, you have a little sex involved because she was raped. It can’t get any better.”

Ramsby sent out a team including her youth-culture reporter, Elizabeth Wolff, a slight, loafer-wearing Brearley brunette. Wolff went to the street that weekend and saw the usual scene: puddles of vomit, women without shoes, men brawling, bouncers hoisting and tossing drunks onto the sidewalk. Some did not look like they would survive the night. “There was this girl—she had been walking toward Eleventh Avenue from B.E.D.,” Wolff recalls. “She had no shoes, she was drooling, and she looked like she was dead. She didn’t look like she was breathing. She just collapsed. Her friends were worried, but, of course, they had lost their other friends. So there was this, ‘Where do we go? What do we do? Do we get our friends?’ Eventually a cop came over and lifted her head and got an ambulance, but she was lying on the ground for 25 minutes before one came.”

By the next weekend, the police had flooded the zone. In the early weeks, there were at least 40 officers, some on horseback. They also brought floodlights, a digital flashing sign warning clubgoers that it’s a crime to show a false I.D., and a large bus, or, as the NYPD calls it, a “mobile command center.” Most serious for the club owners, the police forbade cars from passing through. They even stopped the restaurateur Roberto Vuotto of Naima, who had just run out of fettuccine, from driving in with a fresh batch from the Lower East Side.

“It’s a good block,” says Jon B. “Some people like to be in the middle of the craziness.” He plans to expand into the old Spirit space, taking over another floor in the old Twilo building. “This should be the club district.”

The police and barricades and blinding lights shifted the makeup of 27th Street. It’s now a stressful place for celebrities who seek a modicum of privacy. Shaq, who not long ago agreed to attend a party at B.E.D., gamely removed himself from his car at the Tenth Avenue barricade and tried to walk down the street. By the time he reached the club, several hundred revelers had surrounded him and he almost seemed to be dragging the crowd along. Bono, who recently planned to attend a Massive Attack party at B.E.D., reached the barricades, saw the crowds, and decided not to get out of his car. But for every celebrity or scenester who has abandoned the street, there is someone like Scott Jones, a plastics salesman from Hoboken, who comes to take it all in. “The cops got it blocked off,” he says of the block, “so it must be something, right?”

A few dozen feet away, two police officers man a metal barricade. Several more sit on horseback. The animals snort as if with boredom or disdain and stamp their hooves on the cold concrete. Klieg lights give the street an eerie sheen. Four freezing souls in leather jackets and T-shirts and sneakers—refugees from the Lower East Side, where the underage drinker can still find service—push through the wind toward a red-lit doorway on the north side of the street manned by heavyset men swaddled in coats. “Hi, Disco,” they say. The rope goes up, and the four step inside Bungalow 8.

It’s 2 a.m., and the place is half-full. The breathless rush of people that used to sweep down the middle has yet to arrive, and on this night, anyway, it will never come. Sacco is sticking to her tight door policy—even though her club is making half as much money as it used to. Models who obviously haven’t taken note of the trend toward healthy plumpness sip champagne, simper, and slide into their seats. “It’s not about who you know, it’s how you carry yourself,” says one visibly excited man, tonguing his teeth and working his jaw as he strides with his friend toward the bar in back. “I’m the guy that walked in, said ‘hi,’ paid for my drinks, did my blow in the bathroom, and came out smiling. They respect me for it.”

Nearby, a woman in a decorative dress discusses Jim Morrison and Kurt Cobain. “When you’re an artist, you’re just fucked up,” she says. “You see life like it really is—and that’s why they all die. They’re unable to bear what they see. But sometimes I get a glimpse of it. It’s like I walk out in the morning and I really see it!” The D.J. switches from “Summer of ’69” to “Beat It.” “Like Michael Jackson,” she says to her friend. “Perfect example. He really saw it.”

Sipping vodka and cranberry on the balcony is Nevan Donahue, a 24-year-old Upper East Sider who has partied in New York since his teens. He surveys the room with a mixture of sadness and nostalgia. For a time, before the deaths of Moore and Valle—and, more important, before anyone with money could pay to play—he had come to Bungalow 8 almost every night. It was fun.

CLUB ROW

View every bar, lounge, and club on West 27th Street between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues.