A year and a half ago, on a Tuesday night in October, an ambitious young lawyer named Aaron Charney was working late on the 28th floor of 125 Broad Street—the pin-striped skyscraper near the southern tip of Manhattan that houses the world headquarters of the law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell. Eric Krautheimer, a partner at the firm, was there, too, along with an associate named Gera Grinberg. They were all hustling to meet a deadline on the same project—part of a deal that no one will name because, even now, it’s still pending. No matter, that project would turn out to be the least interesting thing about what happened that night.

Working on the 28th floor means you’re among the elite at Sullivan & Cromwell. Of the firm’s 600 lawyers, fewer than 60— 23 partners and a few dozen associates—are part of the mergers-and-acquisitions group, a sort of firm-within-the-firm that each year advises and executes close to a trillion dollars in deals and earns tens of millions of dollars in fees. All the stereotypes about life at a stodgy white-shoe firm—the masochistic hours, the glorified grunt work, the borderline abuse at the hands of the partners—seem magnified to the young associates there, if for no other reason than that the firm’s blue-chip clients, like AT&T and AIG and Goldman Sachs, need their lawyers on call night and day to meet sudden-death deadlines. To get this kind of work done quickly and accurately, you need a certain tunnel vision—and, when tempers flare, a very thick skin.

Although the vast majority of young associates at Sullivan stay a few years and then write their tickets elsewhere, Charney thought he’d be one of the roughly one in ten lawyers who go on to make partner—and until that night, there wasn’t any reason to believe he would fail. Up from the Syracuse suburbs, he’d graduated in the top 10 percent of his high-school class and ascended to Brown undergrad, Columbia Law, and finally a beige-on-beige office in the M&A group. In his first two years at the firm, Charney was doing better than well: While others were incorporating entities or doing due diligence, he was helping negotiate deal points. “He did work in his second year you wouldn’t get from fourth-years,” says one person who worked with him. At 27, he was young and smart and successful and well paid. And gay, though he made a point of not talking about that at work.

But Charney had at least one problem that he wasn’t aware of. To the other lawyers on the 28th floor, he was a remote figure. Most of the M&A attorneys worked together in groups, but Charney spent his time working behind closed doors, often with Grinberg. When they weren’t busy talking about their off-hours jaunts to Atlantic City or dishing about who might be leaving the firm, the other young lawyers took to wondering what Grinberg and Charney were doing all day on their own. Were they slacking off? Conspiring? Could they be sleeping together? “It was a very gossip-heavy floor, and that was one of the frequent subjects,” one former co-worker remembers. “Actually, most people were weirded out by it.” It wasn’t just about sex: Not everyone knew that Charney was gay, and Grinberg (a few years older than Charney and by all accounts an affable guy) was said to have a girlfriend. It was more that the other lawyers were suspicious of the two who had separated themselves from the herd.

Charney and Grinberg had been pulled away from their usual work for the month of October to help Krautheimer on the project that consumed them that night. The partner was ten years older than Charney and lacked Charney’s educational pedigree—he was a SUNY-Binghamton undergrad and got his law degree at Western New England—but his skills were beyond reproach (he would go on to help lead the highest-valued merger deal of 2006, AT&T’s $83.1 billion buyout of BellSouth). He was paunchier and more rumpled than the treadmill-trim Charney and flouted firm decorum by showing up at the office without a tie and in short sleeves in the summer. Among the associates, he was widely known to be a hard-ass; when he excoriated an underling, he never did it with a smile. So it was with an entirely straight face that, sometime after midnight, the alleged remark was made.

Charney says he had walked into Krautheimer’s office to get a document he needed when Krautheimer tossed the paper onto the floor. “Bend over and pick it up,” Charney claims Krautheimer said. “I’m sure you like that.”

It was a comment that would be shocking and inappropriate in nearly any professional environment. Then again, this was not any professional environment. Associates at big corporate firms are often bullied by partners—beset by tantrums and cruel criticisms. Partners get away with it, it seems, because associates are essentially a fungible resource—easy to replace and therefore hard to care much about. The abuse can even be seen as part of the strange hazing process at corporate firms by which a class of more than 100 associates is whittled down over eight years to a dozen or so people who make partner.

As a firm, Sullivan may be even more hard-core than most. “It’s not a very nice place,” says one lawyer who left, “and that’s the leadership of the firm, from the top down. They’ve turned a blind eye to it for years.” Says another, “Many partners think they’re gods, and they think the associates are worthless shit.” The attitude has led, some say, to unusually low associate morale: In the past few years, the attrition rate for Sullivan’s associates has been higher than the national average for large firms.

None of this excuses Krautheimer’s alleged comment, but it does provide context: It’s possible that the partner didn’t know Charney was gay—that his “bend over” remark was just another way of making Charney feel subservient, of belittling a young hotshot. But to Charney, the incident went to the heart of everything he feared about being a gay man at a corporate law firm. He’d only just come out of the closet, when he was 25 years old, and though plenty of people at the firm were openly gay, including eleven partners (three of them in the M&A group), the question of how to be a gay man and a corporate lawyer at the same time was something Charney still hadn’t entirely worked out. He went into his office, closed the door, and cried. “I was upset, confused, hurt, frightened for the consequences to my career,” he says.

Charney was still trying to figure out what to do the next day when, he says, Krautheimer performed something of an encore. According to Charney, the partner handed him another document and said, “I just took a shit while reading this, and some might still be on there for you.”

Though neither party knew it at the time, these comments would set off a chain reaction over the next year and a half that would lead Charney to file a $15 million anti-discrimination lawsuit and Sullivan & Cromwell to fire back with charges that Charney leaked confidential documents and tried to squeeze the firm for $5 million. The case has captivated the legal world, both for its juicy portrayal of the harsh life of underlings at a stodgy firm (the offhanded bigotry, the boardroom conspiracies, the intimidation, the retaliation, the betrayal) and for its complicated protagonist, who comes off alternately as a noble civil-rights crusader and a paranoid kid with a persecution complex. Is Charney out for justice or a quick payday? Is he Anita Hill or Paula Jones?

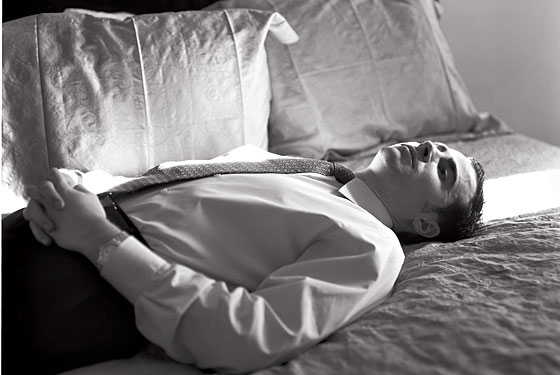

When he opens the door to his apartment, Aaron Charney is without shoes, his black Gold Toe socks exposed. It is a Thursday afternoon, two days after he filed his lawsuit, had his BlackBerry disconnected, and was placed on paid leave—and two weeks before he would be served with a countersuit and fired. Now 28, he looks younger, thin in a purple fitted dress shirt, a Rolex on his left wrist. His underdecorated one-bedroom in midtown has a view of the Statue of Liberty.

In conversation, he’s friendly but guarded, especially when it comes to talking about his personal life. He says he’d never had a gay experience until he was 25—“I wouldn’t call it a relationship,” he says. He wanted all his ducks in a row—the B.A., the J.D., the secure career track—before reckoning with that part of his identity. “You come to a point where you realize that issues are no longer malleable, and you know who you are, and you make a decision,” he says. “You have to really know yourself before you make a decision like that. Because you don’t want to regret it later.”

Long before he knew he was gay, Charney knew he wanted to be a lawyer. The only son of an owner of a small chain of men’s clothing stores in the Syracuse area, he grew up in an upper-middle-class suburb; his teachers remember a hard worker who loved debate and research and writing. At Brown, friends say, he set himself apart from the pack by coming out not as gay but as proudly, passionately conservative. Unlike many secular Jews, he was unequivocally pro-Israel. He had a libertarian streak, urging limited government and no minimum-wage increases. Though Charney was never exactly an activist, he loved to debate. “He said it helped him learn to articulate his positions,” says one friend. “He enjoyed the fight. The fact that he was a conservative while at Brown shows he’d fight the fight.”

At Columbia Law, his conservatism caused him to go “toe to toe with some of the more liberal professors,” a friend says. When he got a lousy grade in a first-year law class, his friends say, he confronted the professor, Eben Moglen, believing he’d been singled out for his conservative beliefs. “I remember he was livid,” says one friend. “He felt like he was wronged. He took it to the administration, and they told him there was no appeals process.” It would be too much to draw a direct line from Charney’s storming the law-school administration to what later happened with Sullivan & Cromwell, but there is one commonality: a sense of entitlement that Moglen says he sees in a lot of law students. “It goes beyond thinking the world’s a meritocracy,” he says, “to thinking you’re entitled to something because of your own merits.” From there, it’s a short leap to feeling wronged whenever things don’t go your way. “It can lead,” the professor says, “to a form of smugness.”

Charney never came close to coming out in college or law school. “It’s one of the issues that you know is creeping in the back room, and you’re not quite sure how it’s going to play out,” he says. He had a serious girlfriend in college. They broke up early on in law school mostly because, he told friends, she wasn’t Jewish. At Columbia, he never seemed to date anyone, male or female. Friends say he asked to be fixed up with women but stacked the deck against a relationship by listing very hard-to-match criteria for his perfect mate. Once Charney did come out, he didn’t tell many of his old friends; they learned about it from his lawsuit.

But in at least one way, he found his tribe at Columbia: More than any other law school, Columbia offers a fast track into the big corporate law firms, and Charney was one of the students who knew this was what they wanted. The summer after his first year of law school, he worked in-house for AIG, the insurance giant that is a huge client of Sullivan’s. There, he fell in professional love. Some lawyers want to prowl the courtroom; others want to shape new laws: Charney was meant for M&A. “Even if you’re on one big deal, at different points of the deal it’s different,” Charney says, enthusiastic for the first time in our conversation. “You have to know a little bit about everything.” Back at school, he interviewed for the next summer’s class of associates. While most students entertain lots of offers before deciding, Charney accepted his offer from Sullivan on the spot.

From his first day at Sullivan & Cromwell, Charney put himself on the fast track, deftly sidestepping the requirement that all associates be “floaters” before settling on one department. His first assignment, in the summer after his second year of law school, was an M&A deal, Anthem’s $4 billion purchase of Trigon Healthcare. He loved it, and the process went smoothly enough that the partners put him on Anthem’s next deal as well: a $16.5 billion merger with WellPoint that created the country’s largest health-care company.

It was on the second Anthem deal that he met Grinberg, a Canadian-born associate with a few years’ more experience. “We were lumped in together for fifteen months and did a really good job,” says Charney. “So, they just staffed us on other things together. Gera actually worked to juggle our schedules so that we would work together.” Though Grinberg was the more senior of the two, at least one lawyer remembers Charney as the more impressive. “Aaron had ambition,” he says. “He was doing great work. I wouldn’t be surprised if he had unblemished reviews. Gera was a nice guy, and he was competent, but he wasn’t a rising star.” (Grinberg would not comment for this story, nor would any Sullivan lawyer whose name appears in the suit.)

Just as he had in law school, Charney felt like a master of the meritocracy, doing the work and getting ahead. But by the fall of 2005, he was entering the adolescence of the typical career life span at a corporate firm: no longer a beleaguered anonymous junior lawyer, now a pressured mid-level associate. This is when even some of the best lawyers get weeded out; alienating just one partner could mean the end of a lawyer’s dreams of making partner himself. But Charney seemed oddly tone-deaf to the office politics on the 28th floor. He came off as aloof—as if he didn’t need to be friends with anyone else as long as he was working with Grinberg on high-level deals. “A lot of lawyers are very smug about their work and their capabilities,” says one former co-worker. “But he came across as smarmy.”

This was also around the time that Charney was starting to come out. The talk with his parents, toward the end of 2004, went well; then there was his first romantic encounter. But there was never a chance for anyone at work to react to his decision. Although he never hid the fact that he was gay, he didn’t advertise it either: He belonged to no gay-lawyer groups and wasn’t active on gay issues. It’s unclear how many people in his department had any inkling he was gay. “I wasn’t that close to that many people,” Charney says. “They may have inferred it, but it was never from me. I didn’t walk around saying, ‘Hey, world. Here I am.’ ” The very idea that he would trumpet his sexuality seems to make him uncomfortable. The firm was still a kind of closet for him.

What did or didn’t happen on that October night in 2005, and in the weeks and months that followed is, naturally, the heart of Charney v. Sullivan & Cromwell. According to one source, Krautheimer is now telling people that Charney’s version of events never happened—though he’s stopping short of denying that he might have said something crude; he just doesn’t remember. Another knowledgeable source says that Grinberg, who allegedly witnessed both comments, didn’t interpret either insult as homophobic. But Charney is unpersuaded. “The tone, the way he did it,” Charney says. “It’s one of those things you never forget.”

A few weeks later, Charney began to suspect that Krautheimer’s alleged bias didn’t exist in a vacuum. At his semi-annual review, he says, he was told by Jim Morphy, managing partner of the M&A group, that he was “one of the best associates” at the firm, that his work was “brilliant” and his efforts “Herculean.” But Morphy also told him several partners were complaining about his being too close to Grinberg: They were “walking the halls together” and “eating lunch together.” This, Charney was told, “needs to stop.” Charney says the subtext was obvious. “I don’t even know what that means,” he says, “other than a homophobic comment.”

There are plenty of others, however, who say that Morphy might have just been trying to give Charney a little friendly advice. For a mid-level associate to work in lockstep with just one older associate, they say, isn’t the way to win friends and influence people at Sullivan & Cromwell. “An ambitious associate wants to work with a lot of people to propel their career,” says one source. “There were circumstances where one would be assigned and two would show up. It’s not behavior that’s even close to typical. We could never have figured out what his abilities were this way.”

Charney was getting a warning: He wasn’t playing the game the right way; he’d better make some adjustments if he wanted to stay on partner track. But Charney had no intention of distancing himself from Grinberg. To do so, he thought, would be tantamount to an admission of guilt. Instead, he defended himself in the review but decided to keep his mouth shut about the perceived homophobia. He had nothing to connect the dots between the lukewarm review and the Krautheimer incidents.

But over the next few months, Charney alleges in his lawsuit, the discrimination became more explicit: An associate named Daniel Serota told him in December 2005 that both Krautheimer and a partner named Alexandra Korry were “disgusted” by Grinberg and Charney and wanted to punish them by “putting the screws” to them. Korry is a powerhouse on the 28th floor—senior to Krautheimer in the M&A department—and, as with Krautheimer, the tales about her mistreatment of associates are legion. Even her devotees admit she is brutal. “She’s very profane,” says one lawyer. “I know plenty of good associates who had issues with her and ended up leaving the firm.” On April 28, Charney alleges, Serota told him Korry believed Charney and Grinberg were in an “unnatural relationship”; she had even started pumping Serota for personal details. Did “unnatural” mean “gay”? Charney asked. He says Serota told him Korry thought Charney and Grinberg were having an affair.

Serota’s new tip, Charney says, was the proof he needed. On May 1, he went to David Harms, co–managing partner of general practice, to lodge a formal in-house complaint of sexual-orientation discrimination. He says he was in tears, not least of all because it forced him to talk about being gay with one of his bosses for the first time. “I don’t want my personal life to be an issue in this building,” he says he told Harms. “I don’t want anyone retaliating against me for coming to you, and I don’t want to have all of these comments and innuendo.”

Sources sympathetic to the firm believe that the messages that came through Serota were wildly misinterpreted. “If she said it’s unnatural working together, the answer is, it was highly unusual,” one source suggests. “If you think you’re being persecuted, you can take words out of context.” But Serota apparently wasn’t finished playing messenger, according to Charney: The day after he complained, he heard from Serota that Korry had e-mailed Harms, calling Charney “a liar” and demanding “all liars should be fired.” When Charney asked Serota to back up his story, he says, Serota refused because Korry terrified him. “There’s no such thing as confidence at S&C,” Charney says Serota told him. Korry would punish him for coming forward. Charney says the two haven’t spoken since. (Serota wouldn’t comment for this story.)

A day or so later, John O’Brien, a gay partner in the M&A group, offered Charney a way out of the mess, telling him, “It’s time we work together.” It was one way to defuse the situation, by getting off the deal he and Grinberg were working on (Kodak’s quest to unload its health-care imaging unit) and onto another project. But Charney smelled a rat. “They were trying to move the chess pieces and lay the groundwork to get rid of me,” he says. “He could write me a bad review and then they could flip it around by saying, ‘It can’t be discrimination because a gay partner is saying bad things about a gay associate.’ ”

On May 10, he got another lifeline. Charney says David Harms walked into his office at 5 p.m. and said that although Krautheimer and Korry had denied everything, Harms had made it clear to them that any bad behavior should stop. If Charney considered the matter resolved and didn’t press his complaint further, he’d have no problems going forward: “You will have no retaliation,” he said. Charney was relieved: “I went home that night thrilled.”

But the next day, he claims, the firm’s machinery started gearing up against him. Charney was shocked to discover that he hadn’t been included on the list of associates who would mentor the incoming class of summer associates. Some say it’s laughable to take offense at this. “I was well regarded over there, and I wasn’t picked as a summer mentor for a couple of years,” says one lawyer. “It’s completely random.” But Charney had spent the last two years zealously recruiting for the firm at law schools; now he felt he was being singled out as a problem child. “Someone who you wanted as the face of the firm—and now you’re removing me from any involvement in any activity in the firm?” he says.

That same day, Charney learned that his discrimination claim was the talk of the department. Steve Kotran, his supervisor on the Kodak deal, allegedly told him that several partners had asked if Charney and Grinberg were sleeping together; some even accused Kotran of enabling the relationship by assigning them to the same deals. There are those who believe Kotran would warn Charney this way; he was known for looking out for younger employees. When Charney went to Harms to complain about the mentor list, Harms reiterated that he should drop his complaint, “let bygones be bygones,” and “move on.” According to Charney, he meant this literally, suggesting a relocation to one of Sullivan & Cromwell’s foreign offices. To Charney, this was the bolt slamming shut on the now-closed door of the firm.

Charney hired a lawyer, and that lawyer, according to a knowledgeable source, suggested a $5 million settlement in a phone call that was promptly reported to the firm’s management committee and then turned down. To this, Charney issues only a partial denial: “There was never anything written to them asking for money,” he says, adding that he fired that lawyer soon after.

Then came the dénouement: On July 6, Charney claims, he had a scathing semi-annual review. He suspected, based on a conversation with Kotran, that the firm was preparing a defense against his discrimination claim that painted Charney as a “management problem.” And here was the beginning of the paper trail. The report claimed that Charney and Grinberg were “running up too many hours when working together,” and “are only willing to be staffed on transactions if they can come on as a packaged deal.” Their “joint-work approach,” the report continued, protects them from blame for any bad work they might do. Charney’s closeness to Grinberg, they said, could be grounds to “drive them out of the firm.” (Grinberg is currently on paid leave.)

Charney decided to file a lawsuit. He started drafting the complaint before Thanksgiving but wanted to wait until the Kodak deal closed before taking action. When the deal was finally done, on January 15, he hadn’t slept in four days. The next day, he filed his complaint with the state court. “My focus was on putting together a document that makes very clear what happened,” he says. “I never spent much time opining about what would happen the day after.”

That seems a bit disingenuous, since he was calculating enough to send copies of the complaint to blogs like Greedy Associates and Above the Law, and Gawker too, ensuring that every lawyer in town could download and dish about it. In fact, it’s striking how far out of his way Charney went to expose everyone involved to public view—even his friends. He named Grinberg in his complaint, when he might easily have redacted his name or called him, say, Associate A. He included an e-mail from Kotran, another purported ally, in which he impolitically says that billing complaints by Kodak are “par for the course.” Charney even included the firm’s partnership agreement in the appendix, a confidential document that reveals, among other things, how much the partners earn after retirement ($255,000 a year).

But the masterstroke of revenge was the mountain of material Charney unloaded about Alexandra Korry, all secondhand: how Serota once refused to work with Korry “because of the daily abuse and profanity-laced scolding Serota had received”; how another associate supposedly moved to the London office just to get away from her; how another associate quit a deal of Korry’s when she shrieked at him, “You’re screwing me!”

Strangest of all, Charney’s lawsuit accuses the firm of being discriminatory against another group as well. Serota, he says, told him that Krautheimer once insulted Grinberg behind his back at a dinner party hosted by Korry—for being Canadian. The firm, somewhat awkwardly, has been put in the position of having to flatly deny any anti-Canadian bias.

The legal world went wild for the Charney lawsuit—Charney’s interview with Canadian television made the rounds online, and the Above the Law blog is still feasting on every morsel of the case—and then went equally wild for the backlash from the firm. Sullivan & Cromwell chairman Rodgin Cohen denied everything—throwing in for good measure that Charney tried in vain to squeeze the firm for a multi-million-dollar cash settlement. Sullivan’s eleven openly gay partners issued a statement rejecting any suggestion that the firm fosters a hostile environment toward gays. Charney wasn’t getting much support from gay- advocacy groups either. The Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund turned down his case. And John Scheich, vice-president of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Law Association of Greater New York (LeGal), told ABC that Sullivan often buys a table at his group’s annual fund-raising dinner-dance and that “if I had to line up on one side or the other, I would have to line up with David H. Braff”—a prominent gay partner at Sullivan. (LeGal has since retracted Scheich’s comment, and Scheich has resigned.)

Braff, who has been out front in defending the firm from any notion of homophobia, tells me, “I came to this firm because of its reputation for being an open environment. I and others helped build on that reputation. It’s very difficult to see someone do damage to this reputation in what I think is an unfair way.” It’s a sentiment that makes Charney furious. “It’s totally unclear to me,” he says, “how somebody who has never met me could suggest that because we sit in the same building and he’s in an environment that he’s happy in, that that is in any way reflective of what’s happening in my environment.”

In February, the firm struck back in court, charging in its countersuit that Charney had turned his lawsuit into “the centerpiece of a malicious public-relations campaign” and accusing him of using confidential documents to make his case, including some that revealed client information. More than that, they accused him of stealing a document from the office next to his and leaking it to The Wall Street Journal, which cited the document in an embarrassing article about Sullivan’s poorly rated associate program. Charney signed two different firms to represent him: the employment-law specialists Herbert Eisenberg and Laura Schnell and the civil-rights-focused Danny Alterman. “Bring your lunch,” says Alterman, a protégé of Bill Kunstler, “because we’re going to be here for a long, long time.”

But it’s Sullivan & Cromwell that’s on the offensive. At a private meeting between Charney, Grinberg, and Sullivan’s lawyers on January 31, the law firm threatened to crush Charney “like a bug,” Charney’s lawyers say. (Sullivan representatives deny the meeting was rancorous.) Charney was apparently so terrified that he destroyed his home computer’s hard drive, twice—first taking it to a store to have it erased, then smashing it to bits. Sullivan’s lawyers, led by litigator Charles Stillman, are arguing this destruction of evidence could be a criminal matter, prompting Charney to add a new member to his legal team: Michael Kennedy, who defended accused murderer Robert Durst.

Neither side has much incentive to settle. For Sullivan, a trial could be messy, but settling could be messier, losing the firm untold millions in revenue from clients who interpret cutting a deal as an admission of guilt. Charney, meanwhile, has nothing left to lose. Assuming neither side blinks, the case will orbit around the question of whom to believe—the problematic young associate or his gruff but respected bosses.

An insult is a complicated and combustible thing. Whatever its intent, one harsh, horrible sentence can be read a thousand different ways. Given how much he wanted to be a partner at Sullivan & Cromwell, it seems incredible that Charney would make up what happened out of whole cloth. Then again, Sullivan & Cromwell is by all other accounts decent to gay people, and no one else interviewed for this story seems to believe Krautheimer and Korry discriminate against gay co-workers. Krautheimer, says one lawyer who has worked with him, is “equal-opportunity rude and nasty.” Another source who knows all the parties posits this theory: “It is at least plausible that Krautheimer and Korry—not based on homophobia but just on the fact that they didn’t like this guy—just ganged up on him. And she makes the mistake of talking with one of his friends who’d worked exclusively for her. The firm really should have nipped it in the bud.”

Charney, too, could have stopped this long ago. He could have taken the deal Harms offered—to let bygones be bygones, to move to another part of the department. He could have answered one of the many headhunter calls that mid-level associates receive. But Charney—by virtue of his principles, his paranoia, or his naïveté—chose to go all the way. He deserved justice; he thought he was entitled to it.

During our last interview, a few days before the countersuit was filed and his lawyers persuaded him to stop talking to the press, Charney seems strained—but his only regret is how other people behaved. “Since I went to complain in May,” he says, “my disappointment in the conduct of people in positions of authority who could have changed this … Disappointment isn’t even the word. It’s the extreme.”

Would he have done anything differently? He shrugs. “I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about what people think.”

The case is his new career now. And nearly everyone believes that once it ends, so will his life as a corporate lawyer. When I ask Charney about this—if he thinks he’ll have to change careers—I’m not prepared for his answer.

“I truly don’t know,” he says. “In an ideal world, this would run its course, the people who have done something wrong would be punished, and the firm would take steps to change the environment. I would come back and return to my career.”

After everything that has happened, he still dreams of working at Sullivan & Cromwell.

“Is that impossible?” he asks.