T his is the sound of a presidential boomlet. Not that it seems like that at the moment. It’s Friday evening, January 12, and America’s Mayor, copyright pending, finds himself in Wilmington, Delaware, at the crusty Hotel du Pont, for what appears to be a routine stop on the rubber-sole-and-rice-pilaf circuit. Tonight, Rudolph Giuliani is receiving an award at an annual gala held by former governor Pete du Pont, the preppy descendent of the hotel’s founder who is best known for conducting an honorable pro-choice 1988 presidential campaign, which, as Rudy must surely know, resulted in zero delegates.

The 300 Republicans arriving for cocktails look desperately in need of them. And with good reason. It’s just two days after the speech in which President Bush conceded, sort of, that mistakes were made in Iraq, then unveiled his plan to send 20,000 more troops there. Congress has just reverted to the Democrats, and Hillarymania and Obamamania are sucking up all the political oxygen.

Rudy is cranky, too. The year is barely two weeks old, and it’s already off to an epically bad start. Right after New Year’s, a 126-page confidential campaign memo concerning a potential Giuliani presidential run fell into the hands of the Daily News. His campaign hadn’t even begun, and there was already a crisis. It was hard to tell which was more embarrassing: the cataloguing of Rudy’s potential weaknesses or the battle plans outlining the courting of GOP moneymen already committed to John McCain. It all suggested a kind of amateurism: My First Presidential Campaign brought to you by the folks at Playskool.

A few hours before his speech, Giuliani inadvertently wanders into a sparsely populated press room. He looks older and wearier than the last time we saw him. There’s the same dark suit, but the undertaker hunch is a bit more pronounced. When a reporter asks what he’s doing here, Giuliani skips the friendly kibitzing. Instead he snaps, “I’m calling my wife. I need privacy.” It’s been said that 9/11 softened Rudy’s edges. If there really is a kinder, gentler Giuliani, he’s not showing it.

Right, 9/11. Out in the dining room, after the salads are served, Delaware congressman Mike Castle takes the microphone. He talks about Rudy and the squeegee men. BlackBerrys continue scrolling. But then Castle tells of the ground-zero tour the mayor gave him and other congressmen in the days after the terror attacks. People start to pay attention. “He attended most of the funerals; he was there in every way possible,” says Castle. “I don’t think we can ever thank him enough for what he did.”

Now Rudy strides to the podium. The room rises. Suits at the cheap tables stand and a banker type sticks his fingers in his mouth and gives a loud whistle.

Initially, Giuliani squanders the goodwill. A bit on immigration lands with a thud. He notes that China has built more than 30 nuclear reactors since we last built one. “Maybe we should copy China.”

What? You can see the thought bubbles forming over people’s heads: Can this be the same guy we saw on television? The guy who was so presidential when our actual president was MIA?

But then Rudy finds his comfort zone. Along with McCain and Mitt Romney, his best-known fellow Republican presidential contenders, Giuliani is out on the thin, saggy pro-surge limb with the president. But Rudy can spin the issue in a way McCain and Romney, not to mention Hillary and Barack Obama, cannot. And now he does just that: Iraq leads to 9/11, which leads to the sacred image of construction workers raising the flag over ground zero.

“I knew what they were standing on top of,” Giuliani says. “They were standing on top of a cauldron. They were standing on top of fires 2,000 degrees that raged for a hundred days. And they put their lives at risk raising that flag.”

The room is silent. Not a fork hits a plate, not one gold bracelet rattles.

“They put the flag up to say, ‘You can’t beat us, because we’re Americans.’”

The mayor pauses and, as if on cue, an old woman sniffles.

He continues. “And we don’t say this with arrogance or in a militaristic way, but in a spiritual way: Our ideas are better than yours.”

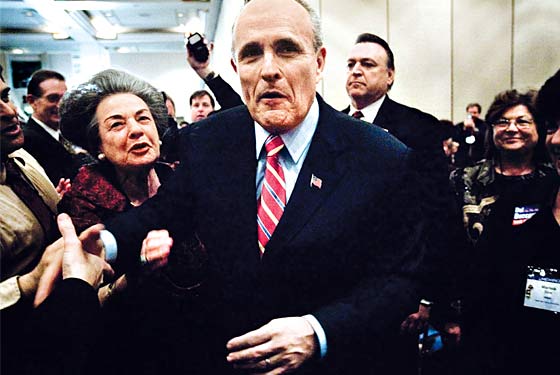

Applause reverberates off the chandeliers. Millionaires pump fists. Dowagers daub eyes. This is what they came to see! Seemingly every law-enforcement officer in Wilmington appears with a camera. Over and over, Giuliani grips and grins.

It may sound preposterous to a Rudy-savvy New Yorker. But in this ballroom full of lock-jawed Wasps, it sounds like presidential salvation.

Can Rudy Giuliani ride 9/11 all the way to the White House? That appears to be his game plan. Beginning that night in Wilmington, Giuliani spent much of the first two months of the year barnstorming around the country—New Hampshire, South Carolina, California—on his unofficial presidential-campaign rollout tour (unless you count his multiple pseudo-announcements, Giuliani has yet to formally declare his candidacy). In many respects, it’s been the standard early-season-campaign drill: Rudy has floated and discarded whole concepts, artfully repositioned his personal history, and studiously avoided all but the most friendly media.

On most issues, his spiel doesn’t sound that different from those of McCain and Romney. But there’s one exception. Over and over again, wherever he goes, America’s Mayor evokes 9/11. And over and over again, wherever he goes, people cheer. Whenever Rudy talks about anything other than the September 11 terror attacks, he’s just another Republican presidential hopeful with his particular set of strengths and weaknesses. When he talks about 9/11, he becomes something else: a national hero.

New Yorkers may find that hard to believe. Anyone who lived here at the time remembers the 9/10 Rudy: strong on crime and the economy, yes, but arrogant, bullying, and terrible on race and civil rights. And while it’s impossible not to respect what Giuliani did for the city on 9/11 and in the days afterward, New Yorkers have experienced an inevitable September 11 fatigue. The 9/11 story has been told so many times that the Rudy-as-hero narrative, however moving, has lost much of its power. Except for those who have a personal connection to the tragedy, people have generally moved on. Besides, it’s common knowledge that a pro-choice, pro-gun-control, pro-gay-rights, thrice-married Catholic northeastern Republican is unelectable, right?

The rest of America sees a far different Rudy. West of the Hudson, the 9/10 Rudy doesn’t exist and never did. For them, September 11 was never so much a real day as a distant televised drama. It has more symbolic meaning than actual meaning: It’s equal parts Pearl Harbor and resurrection. And guess who plays the role of national savior? Not George Bush. Not John McCain. Not Barack Obama or Hillary Clinton.

Once the rest of the country sees Giuliani up close, the conventional New York wisdom once held, his campaign will surely fold. So far, exactly the opposite has happened. The more Rudy has put himself out there, the higher his numbers have climbed. Last week, a CBS poll showed Giuliani leading McCain by a whopping 21 points while a Quinnipiac survey found Giuliani running five points ahead of Hillary nationally, and dead even in blue states.

Yes, Rudy is the new horse in the race and thus, for now, the most compelling. Much of his popularity comes from the fact that he’s entered the race just as McCain’s ties to George Bush’s Iraq policy threaten to render his once inevitable nomination stillborn. At the same time, an idea has taken root that the 70-year-old Arizona senator, cancer survivor, and former POW, who would be the oldest person ever elected president, won’t be up to the job.

Giuliani’s pro-war stance and his moderate social-issue positions may yet bury him. So could a lack of money, a green campaign staff, his thin political résumé, his trifecta of marriages, and, not least of all, the fact that the 9/11 card, however powerful it is, could simply prove too flimsy to carry him all the way to the White House. With 21 months to go before Election Day, there’s still more than enough time for McCain to reassert himself—or any number of other scenarios to play out that don’t involve Giuliani’s becoming president. Still, no Republican presidential candidate in modern history has held this big a lead a year out and not scored the GOP nomination.

Believe it or not, America’s Mayor could be America’s next president.

I t’s nine below zero in Bretton Woods, deep in New Hampshire’s North Country. The snow crackles under a cavalcade of SUVs creeping up the driveway of the mammoth Mount Washington Hotel. The hotel once hosted FDR for a pivotal 1944 conference on postwar monetary policy. Now here’s Rudy speaking at the Littleton Chamber of Commerce’s annual supper. It makes sense, of course. New Hampshire still holds the nation’s first primary, and Rudy needs to test his material way, way out of town. On this, Giuliani’s first ’07 trip to the state, he has his third wife, Judi, in tow. The would-be First Couple looks a bit mismatched as they say hello to a pack of Girl Scouts stationed near the door selling cookies. Judi is all glamour in pearls and a black turtleneck. Rudy is in need of an ear-hair trimmer. But Giuliani proves he’s no George Bush the Elder—he whips out a fist-size wad of cash and gives the girls $80 for $70 worth of cookies.

September 11 comes up even faster than Rudy could have expected. One of the scouts tells Giuliani that she lost a cousin that day. Rudy smiles a bit and touches her on the shoulder while Judi gives her a hug. The girl asks how the mayor made it through that day. “With the help of loved ones,” he replies. The little girl smiles. Afterward, I ask the girl what her cousin’s name was. “I don’t know, I never met him,” she says. By now, another blonde girl, maybe 11, is tugging on the mayor’s sleeve. “You’ve been my hero since 9/11.”

There’s more 9/11 bathos—New Hampshire seems awash in it. Holding hands, Rudy and Judi are shuttled into a conference room for photos. When Rudy emerges, Jan Mercieri, the wife of a local fire chief, asks him to autograph Portraits: 9/11/01, the New York Times book of short biographies of the 9/11 dead. Giuliani signs, Mercieri gets teary, and they embrace. Mercieri is then deluged by the media pack. What did he say? What did he write? What does she think about his stance on abortion? “Those issues don’t matter,” said Mercieri. “After 9/11, I’d vote for him in a second.”

Up on the dais, it’s Rudy’s turn to raise the subject of the terror attacks. September 11 is proving to be a versatile tool. In Delaware, he used it to invoke heroism. Here, it’s all about scaring the bejesus out of country folk. Someone asks him what his management style would be as president if there was another Katrina or terrorist attack.

The secret is to be prepared for anything, Rudy says. Terrorism can happen in New York or Boston or in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, “one of the smallest towns in the United States.”

The punchy good cheer of this small town is replaced with grave attention. Rudy notes that he once spoke to the Shanksville high-school graduating class. “But for the grace of God and the bravery of the people who brought that plane down,” he says, “those kids wouldn’t be with us.”

Tonight’s attendees, of course, have a far greater chance of being killed on an icy road on the way home tonight than via a plane falling out of the sky. But those are facts; Giuliani is playing on emotion and fear.

After his speech, Rudy never gets a chance to eat. There are too many people wanting pictures, too many people wanting a hug, too many people offering one variation or another of what one woman says: “Thank you for keeping us safe.”

Before 9/11, the idea of Rudy Giuliani running for president would have been laughable. That morning, Giuliani had breakfast at the Peninsula Hotel with Bill Simon, a longtime friend. Simon, a business executive and the son of a former Treasury secretary, was contemplating a 2002 California gubernatorial bid. Giuliani agreed to help, but wasn’t sure he would be of much assistance. “I could endorse your opponent,” joked Giuliani. “That might help you more.”

A few minutes later, Giuliani’s cell phone rang. As the towers fell, President Bush read a children’s story, and Dick Cheney disappeared into a bunker, Rudy Giuliani was in harm’s way. By 11 a.m., he was on television asking for calm. That night, he famously proclaimed, “New York is still here. We’ve undergone tremendous losses and we’re going to grieve for them horribly, but New York is going to be here tomorrow morning. And it’s going to be here forever.”

By the end of that day, Rudy was no longer just a big-city mayor with a mixed record. He was a legend.

September 11 has been Giuliani’s alpha and omega ever since. After leaving office, the mayor formed Giuliani Partners, an omnibus security-consulting firm. Giuliani offered his clients his post-9/11 expertise—and his gold-plated name; in return, they paid handsomely and basked in his fame. Mexico City paid Giuliani’s firm more than $4 million to help make its city safe. The makers of OxyContin hired Giuliani to beef up their security, and to help persuade the federal government not to curtail access to what came to be called “hillbilly heroin.” (Giuliani recently moved to divest himself of the investment-banking arm of Giuliani Partners, Giuliani Capital Advisors, to avoid potential conflicts.)

Giuliani became a rock star on the speaking circuit. At first, he did the events for free. Eventually, he would charge $100,000 an outing. Last year, Forbes estimates, Giuliani made $8 million from speaking gigs.

Since 2002, Giuliani has also used his 9/11 fame to help his fellow Republicans, stumping for more than 200 of them, and collecting valuable political chits in return. In a three-day period the weekend before the 2006 elections, as we learned from the leaked campaign memo, Giuliani appeared on behalf of GOP candidates in Florida, Virginia, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania.

Everywhere he went, he played the 9/11 card, dismissing the Democrats as squishy on terror. More often than not, it worked. “Ask anyone, and they will tell you that their Giuliani event raised the most money,” says Ralph Reed. (Last year, Giuliani campaigned for the former director of the Christian Coalition during his unsuccessful, scandal-marred run for Georgia lieutenant governor.) “People don’t forget that.”

On Meet the Press the Sunday before the 2004 election, Giuliani told Tim Russert that Osama bin Laden “wants George Bush out of the White House.” It may have been crude, it may have been crass, but just about everyone allowed it was effective.

Why does 9/11 play so well for Rudy? Our Calvinist streak dictates that the greater the adversity a man overcomes, the more we worship him—and Rudy certainly overcame adversity on 9/11. “Here on the coasts, we make fun of heroes,” says presidential historian Douglas Brinkley. “We think it’s hokey. But the rest of America craves heroes. To them, Rudy’s like Eisenhower. Mothers bring their sons to see him.”

Post-9/11 events have only made Giuliani more exalted. The more the war on terror bogs down, the better he looks. September 11 has spawned two wars, cost us 6,000 American lives here and abroad, and produced precious few heroes. Those we got wilted under scrutiny. Donald Rumsfeld turned out to be a nut job, Jessica Lynch may or may not have actually needed to be rescued, and Pat Tillman was killed by friendly fire. There have been no Pattons, no MacArthurs, no Eisenhowers. There is only Rudy.

Outside of New York, there is a still-unsatisfied appetite for revenge (that hunger seems to get stronger, strangely enough, the farther one gets from ground zero). Bin Laden is still at large. Saddam Hussein, it’s now tragically clear, had nothing to do with the terror attacks, however awful his other transgressions were. People seem to believe—wish?—that Rudy can somehow bring us justice. Who else could at this point?

To many Americans, Rudy fills the leadership vacuum created by Bush’s bungling of the war and Katrina. Joe Trippi, Howard Dean’s former campaign manager, recalls running a Democratic focus group for a 2005 mayoral candidate in Los Angeles. “We were asking what they were looking for in a leader,” Trippi says. “One guy said, ‘Why can’t we have someone like Rudy?’ Then everyone joined in, saying ‘Yeah, we need a Rudy. We need a Rudy.’ ” Those were Democrats, and this was 2005. “It’s still that forceful,” says Trippi.

September 11 also gives Giuliani at least some credibility on the signature issue of the campaign: Iraq. So what if Rudy doesn’t have a shred of foreign-policy experience? The perception goes something like this: hero of 9/11 = expert in the war on terror = strong commander-in-chief.

September 11 could even help Rudy win over the hard right. Evangelicals see the war on terror as nothing less than a metaphysical battle for the soul of Christianity, with Rudy the Lionheart as their crusader. “Rudy has created great brand equity on terrorism with Christians,” says Reed. “They won’t give him a pass, but they’ll listen on the other issues.”

Rudy’s comment suggests a broader point: 9/11 gives Rudy a kind of golden glow that makes all his positives seem a bit more positive and all his negatives a bit less negative.

Never mind the southern hospitality and softly swaying palmetto trees. South Carolina is the killing fields of Republican presidential politics. Just ask John McCain. He arrived in 2000, fresh from his win in New Hampshire, as the Republican front-runner. Two weeks and a flurry of push-poll attacks later (telephone polling suggesting McCain fathered a black child out of wedlock was the most notorious), he was finished.

Eight years later, on a February Saturday, Rudy Giuliani arrives in Columbia to address the South Carolina Republican Party. Outside Seawell’s conference center, there are rumors that a pro-life picket line is going to materialize. It doesn’t, another break in a month of breaks for Rudy.

Inside, it’s a folksy affair. Chairman Katon Dawson, an excitable auto-parts salesman, gavels the meeting to order. He then asks the county chairs to introduce any guests. Fishing buddies and dads stand up and wave. This takes a while.

Finally, Dawson introduces Giuliani. There’s mention of Rudy’s crime-busting, budget-balancing ways—and, of course, September 11. “Rudy Giuliani,” says Dawson, “is known around the world as a symbol of the resilience of the American spirit.”

In seven minutes and change, Giuliani goes to 9/11. “Before September 11, we were playing defense,” he says. “President Bush said we can’t do that anymore. We have to go on offense. We have to go look for them and stop them before they come here and attack us.”

This may be the only place in Christendom where Bush is still popular. Everyone cheers. “The next president of the United State is going to have to continue to deal with this,” says Giuliani. “If you don’t think you’re going to have to deal with it, you’re not looking at the real world and you’re not going to be able to keep this country safe.” There’s more clapping (although it’s unclear which presidential candidate thinks the war on terror is about to end. Dennis Kucinich?).

Giuliani throws the crowd a few extra chocolates, parroting the White House line of Bush as Truman, a prophet who will be vindicated by history. It’s not until Giuliani has deposited as much 9/11 goodwill in the bank as possible that he addresses the real issue of the day. Dawson solicits questions from friendly faces. Eventually, someone asks Giuliani what his approach would be to judicial appointments.

“On the federal judiciary, I would want judges who are strict constructionists,” Giuliani answers. “I have a very, very strong view that for this country to work, for our freedoms to be protected, judges have to interpret, not invent, the Constitution.”

Down here, of course, constructionist is code for pro-life. Supporting constructionist judges while remaining pro-choice is a Clinton-quality triangulation: It keeps the pro-lifers at bay without a Romney-esque flip on abortion. Half the crowd whoops, half sit on their hands. No one boos, perhaps out of deference to 9/11.

But even 9/11 has its limits. Later, I do a little push-polling of my own. I ask Max Kaster, a local pastor and party chair for Calhoun County, a half-hour south of Columbia, what people down here would think of America’s Mayor if they knew he had moved in with a gay couple after separating from his second wife. “Really?” Kaster says. He fiddles with a lapel pin that combines an American flag and a cross. “I think that would roll a lot of people’s socks down.”

September 11 or no September 11, Rudy’s still vulnerable on social issues. No matter how skillful his pandering, there are those on the right who simply won’t vote for a pro-choice, pro-gun-control, pro-gay-rights candidate. Giuliani’s supporters like to point out that the South is trending more moderate. Still, Rudy is seeking an office that has been held by a centrist southern Democrat or right-leaning Republican southerner or westerner for four decades. The last president from the northeast was JFK.

It’s true that 9/11 gives Rudy credibility on Iraq, but not much. If the war continues to go badly—as just about everyone believes it will—Rudy’s pro-Bush, pro-surge stance, like McCain’s or anyone else’s, for that matter, could still derail him.

Rudy’s lack of experience is a weakness as well. The highest elected office Giuliani has ever held is mayor, and no one has ever made the leap straight from City Hall to the White House. The chatter among political insiders is that even 9/11 can’t cover that up. “There’s a reason Giuliani’s using 9/11 as an asset,” says Bob Shrum, political consultant to a half-dozen Democratic presidential candidates (not to mention David Dinkins). “It’s his only asset. He’s not even running on his mayoral record. He’s running on a few weeks. September 11 doesn’t change the fact that Rudy has no foreign-policy experience, and his foreign-policy record is limited to having the same position on Iraq as George Bush.”

Rudy’s campaign team is green in terms of national elections. His inner circle remains the same as that of a decade ago: Peter Powers, a longtime Rudy friend and former chief deputy mayor, lawyer Dennison Young, aide de camp and former chief of staff Anthony Carbonetti, and spokeswoman Sunny Mindel. Outsiders are viewed with skepticism, and Memogate, to their way of thinking, only justified that attitude. (Fingers were quickly pointed at Anne Dickerson, the campaign’s head fund-raiser and a former Bushie. She was summarily demoted to consultant.) Naming Mike DuHaime as campaign manager in December didn’t particularly impress political pros. Although talented, the 33-year-old DuHaime is not a proven winner. In 2000, he was deputy campaign manager of a failed New Jersey Senate run. In 2004, he ran Bush-Cheney’s Northeast campaign, which resulted in no breakthroughs and the switching of New Hampshire from red to blue. In the last cycle, DuHaime was the RNC political director in the year when the GOP gave back Congress.

On the policy side of the campaign, Giuliani insiders speak reverentially about the candidate being put through “Simon University,” a series of informal public-policy seminars chaired by Bill Simon. Alas, Simon is perceived in his native California as something of a lightweight. His 2002 California gubernatorial bid was essentially a series of train wrecks punctuated by the release of a photo purporting to show then-Governor Gray Davis receiving a campaign check in his office, an illegal act. The only problem was, the image turned out to be from somebody’s home. In New Hampshire, Giuliani hired outgoing state party chairman Wayne Semprini as his state director. Semprini was party chair for only one year, just long enough for his party to lose two congressional seats and the statehouse. In Iowa, Giuliani has been slow out of the gate; his biggest announcement was the support of Congressman Jim Nussle. Like Simon, Nussle’s claim to fame was a failed 2006 gubernatorial campaign.

Money-wise, Rudy has lined up some top-shelf donors, including Home Depot founder and former New York Stock Exchange director Kenneth Langone, whose Wall Street connections could bring millions. He also has the support of Roy Bailey, a former finance chair of the Texas Republican Party who provided some of the seed money for Giuliani Partners. Last month, Bailey organized a Houston fund-raiser for Rudy that raised hundreds of thousands of dollars. In California, Bill Simon recently coordinated a series of well-attended fund-raising events as well. But John McCain’s alliance with Bush, reluctant though it may have been, locked up GOP rainmakers like Texan Robert Mosbacher and lobbyist Thomas Loeffler a long time ago. And because Rudy was relatively late to the table, he may have missed landing the support of potentially sympathetic high rollers like Henry Kravis. Still, it’s early in the game for everyone—no one has yet raised anywhere near the money they’ll eventually need—and money flows from poll numbers. Anyone who can get and maintain a lead still has enough time to raise a fortune.

If all of those issues weren’t enough, there’s also Rudy’s temper. Sooner or later, Giuliani will have to endure scrutiny—and lots of it—on issues he doesn’t want to talk about. September 11 may well have mellowed Rudy (friends insist it genuinely has), but it remains to be seen if he can avoid being baited into exhibiting the kind of behavior that once made Jimmy Breslin call him “a small man in search of a balcony.” Maybe not. In California, I asked Giuliani if he has, in fact, softened. He laughed dismissively, then said, “Is there a mellower version of me? I don’t know. Other people are a much better judge of what versions there are of me. I am who I am.”

When you see Rudy and Judi together, it’s clear the couple is in love (a point they may have made too forcefully in an over-the-top March Harper’s Bazaar photo spread). And while some people see Judi as too slick for Middle America to embrace, others say she softens him. Regardless, the Judi game is tricky. One way or another, seeing her reminds people of the infamous Donna Hanover affair (Rudy informed the mother of his two children that he was divorcing her via press conference), not to mention the fact that Rudy’s first marriage was annulled on the grounds that he unwittingly married his second cousin (his defense was that he thought she was his third cousin).

Even 9/11, Rudy’s alleged magic bullet, could prove problematic. At some point, Rudy will inevitably air ads featuring heroic shots of him at ground zero with a voice-over that sounds something like, “On America’s darkest day, one man stood tall.” But overplaying 9/11 in any way is not without peril. “With most presidents, there’s a modesty to their heroism,” says Brown University historian and former Clinton speechwriter Ted Widmer. “George H.W. Bush was a war hero, but he didn’t talk about it. Eisenhower never used it. You have to be careful not to overinflate it.”

Or September 11 could simply lose its power. Right now, 9/11 is about all most voters know about Giuliani. “He’s like McCain in 2000,” says Mark McKinnon, the former George W. Bush consultant who is now working with McCain. “He’s a vessel people are pouring things into.” But in time, that could change. “Giuliani has legions of fans in the Republican Party, including President Bush, John McCain, and me,” McKinnon is careful to note. “But I think the traditional physics of a presidential Republican primary will be difficult.” That’s a savvy political pro’s way of saying his opponent will get creamed when the press starts looking more closely at him. Then again, McKinnon allows, “Conventional wisdom could go out the door, and the celebrity Rudy justly deserves will allow him to soar above the usual fray, and he’ll be president.”

In the end, of course, elections are about matchups. Right now, Romney, mired in single digits, is not a factor, which means the bid for the Republican nomination for the moment appears to be a two-man race: Giuliani vs. McCain.

In certain respects, Rudy measures up well in that fight. Yes, the two men hold essentially the same position on Iraq. The difference is that Giuliani is linked with Bush at ground zero in all the macho swaggering ways. McCain is linked to Bush as a bumbling quagmire creator. McCain may have conducted the war better if he had been president and he may have been an articulate critic of the Bush-Rummy fiasco, but voters see him as part of the problem, not part of the solution (assuming a solution exists). To them, McCain is a Washington insider walking lockstep with a hugely unpopular president. For the time being, anyway, Giuliani gets the 9/11 free pass.

In the battle for the hearts and minds of the religious right and social conservatives, neither Rudy nor McCain will ever be accused of being a movement conservative. In 2000, McCain called Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson “agents of intolerance” for their role in smearing him in South Carolina. He’s since made peace with both men, and even spoke at Falwell’s Liberty University. Last week, McCain announced that as president he would support the repeal of Roe v. Wade. The move was viewed by some observers as the senator’s first direct reaction to Giuliani, an explicit statement to the Christian right that he is on their side while Rudy, despite his constructionist-judges talk, is still officially pro-choice. Still, true believers can carry a grudge, and they’ve never liked McCain. And Rudy can play the 9/11-crusader angle to try to counter his morally wayward ways.

In the end, however, McCain may have the more meaningful advantages. Not only do his fund-raising and campaign operations compare favorably with Giuliani’s, but McCain has done this before. He’s also got a heroic story of his own, and he can clobber Rudy on the experience issue (four-term senator, ranking member of the Armed Services committee, champion of campaign-finance reform).

But let’s say Iraq continues to implode, and McCain proves too tarnished by his association with Bush to survive the fallout. No other credible candidate emerges, and Rudy somehow convinces Republican America that his handling of 9/11 and his stewardship of the country’s bluest city qualify him to be their candidate for the highest office in the land. Let’s say Rudy wins the nomination. Then what?

Conventional wisdom suggests if a Democrat can’t get elected president in 2008, the whole party should just pack it in. Still, Rudy creates problems for all three of the current front-runners. His weakness in the primaries—his centrism—would become a strength in a general election (and he’d only tack further to the middle at that point). Rudy’s lack of experience would be mitigated by Hillary’s, Obama’s, and Edwards’s own relatively thin political résumés (leaving aside her time as First Lady, Hillary’s got just six years as a senator, while Edwards has only one term, and Obama is in his first term). In some ways, all four candidates are running on image as much as anything. And Rudy’s 9/11 pitch is at least as appealing as anything Hillary, Obama, and Edwards are selling.

Still, the defining issue will again be Iraq. If there’s no turnaround, there’s no Rudy victory, certainly not against Obama (who has opposed the war all along) or Edwards (who now calls his war vote a mistake). Ironically, it’s Giuliani’s erstwhile 2000 Senate opponent who gives Rudy his best shot. Hillary Clinton’s Bush-like refusal to say “I made a mistake” makes her somewhat more vulnerable on Iraq. Rudy, meanwhile, has been careful to leave himself wiggle room on the issue by saying that he recognizes the troop surge may not work (at the same time, to protect his right flank, he’s careful to insist that whatever happens in Iraq, the broader war on terror must go on). And despite the fact that she’s not the demon she once was to the right, Hillary’s very presence on the ballot will still drive many hard-right Republicans straight to the polling place.

Of course, there is a wild card. George Will recently called Rudy the best answer to “the seven-minute question”: Which candidate is most capable of analyzing and responding to a global crisis? It may be an awful stereotype, but if there’s another terrorist attack in the summer of 2008, a lot of suburban moms who may lean toward Hillary or Obama or Edwards will, in the privacy of the voting booth, pull the lever for Rudy.

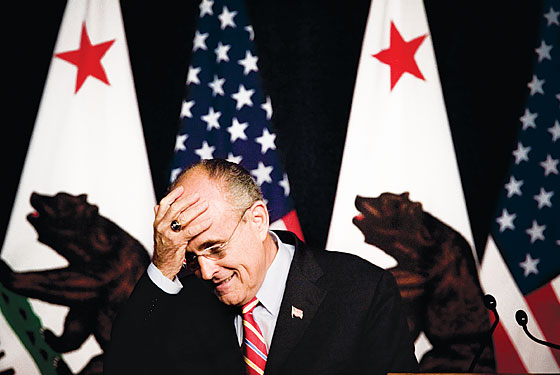

It’s a mid-February Tuesday, and Giuliani is in California’s Central Valley for the opening ceremonies of the World Ag Expo in Tulare, a.k.a. “The Greatest Farm Show on Earth.” With the Golden State threatening to move up its presidential primary next year to early February, California suddenly looks a lot more important than it used to. Rudy, in the midst of a weeklong trip, has already spoken to Silicon Valley tycoons, keynoted the state Republican convention, and smoked a cigar with Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Today dawns overcast, but eventually the sun pokes through, giving glimpses of an endless blue sky. Amid the almond fields, overalls, and talk of irrigation reform, no place in America seems farther away from that gray, dark pit in lower Manhattan.

Still, five minutes into his speech, Rudy Giuliani, casually dressed in blue blazer, black loafers, and a V-neck sweater, finds his way to September 11. The mayor begins by admitting he doesn’t know much about ag policy, but that he’s a quick study. What he does know, he says, he learned on 9/11.

“We depend on each other. I always knew that, but that really got into my heart, my soul, in a way I’ll never forget, on September 11, 2001,” says Giuliani. “You realize how much we depend on each other. We depend on you a lot for food for sustenance.”

Rudy’s taking 9/11 local again, and he keeps working it. He tells the farmers what they could learn from that day. “We made a mistake on energy. I just met two Marines who were wounded in Fallujah before I came in here. It is very frustrating in a way that goes deep into our heart; we got to send monies to our enemies to protect a lifestyle in America. We can’t let it happen with food. The American farmer is the most productive, most innovative farmer in the world.”

The crowd cheers. Giuliani continues with his standard “They are at war with us” speech. But today, he adds a new wrinkle. “It was a very, very strange accident of fate or whatever, but I was in London, a half block away from the first bomb that went off a year and a half ago. I was six miles away when the first plane hit the World Trade Center and one mile away when the second plane it. I’ve lived through these attacks.”

This time, the crowd nods but doesn’t clap. The London addendum hit a bum note. It’s as if Rudy’s trying to make himself out to be the Zelig of terrorism. For the first time, he might have overplayed 9/11.

By now, however, the 9/11 song is so familiar that Rudy quickly finds his way back to the beat. “They believe their perverted ideas are stronger than our belief in democracy, freedom, decency, and the rule of law.” He pauses and surveys the room full of fourth-generation Japanese farmers, tractor salesmen, and a lone bagpipe player. “And they’re wrong. Absolutely wrong.”

There is a standing ovation.

After his speech, Giuliani is golf-carted to a nearby exhibition to try out some of the new farm gadgets. He even screws in a few screws with a newfangled drill. For no clear reason, a Marine in dress blue is never too far from the mayor’s side.

“You’re gonna run, right?” asks a worried farmer. “Don’t let us down.”

“I won’t,” promises Giuliani.

Then the former mayor of New York, standing in a California farm field surrounded by tractors and a two-story-tall thresher, pulls out a Sharpie, and signs a few more autographs.