Richard Stengel removes his jacket and rolls up his sleeves like a man readying himself for a stump speech. Tall and wanly handsome, with an off-center smile, Time’s new managing editor is facing a room full of 100 former editors, publishers, and photographers from the magazine’s venerable past. Largely white-haired, many balding, some hobbling on canes, not a few cupping their ears to hear, the members of the Time-Life Alumni Society are here to find out what brave new direction Stengel, 51 years old and eight months into his tenure, will take the 84-year-old weekly.

“The ultimate mission about sustaining Time is about greatness,” he declares from the podium. “One of the things we’re doing in the future is trying to be selective, go for the best. I believe that is what Time always was. I believe that is what will make Time great again.”

A former advertising executive, sitting in a darkened corner, raises his hand.

“Hasn’t Time magazine’s time passed?”

The room goes silent. “And you are an alumni of this society?” asks Stengel, getting a nervous laugh from the audience.

“It was launched 80 years ago!” says the man, before uttering a sentence that hardly needs to be spoken. “It was a very different world then.”

When it’s the faithful who are questioning the relevance of one of the oldest and most sacred magazines, you’ve got a problem. Of course, it’s a problem they’ve had for some time. The magazine started by Henry Luce and Briton Hadden in 1923 to condense a week’s worth of newspapers into a one-stop digest has been declared headed for the proverbial dustbin for at least twenty years, ever since the advent of cable news. But today, with the fundamental business model of publishing under assault as never before, even Time Inc. acknowledges that Time is at an “inflection point”—a corporate euphemism for the witching hour.

That is why the magazine is in the midst of what its publisher, Ed McCarrick, is calling a “revolution,” led by Stengel and the man who hired him—John Huey, the irascible editor-in-chief of the magazine’s parent company, Time Inc. Having spent their careers getting to this moment, neither Huey nor Stengel wants to preside over the death of a great American magazine.

After a long pause, Stengel manages an answer to the adman’s skepticism.

“Even twenty years after Life magazine stopped publishing, it was still one of the most venerated and recognized brands among Americans,” Stengel argues. “There’s a power and a value to that. And I think we can piggyback on the power of our brand, to help make it essential reading today.”

It’s an odd reference, given that Life has come to represent epic magazine death, proof that even the biggest brands can fall.

Stengel came of age at Time, incubating on the 24th floor of the Time & Life Building along with a generation of writers who now make up a significant chunk of the media Establishment. There was Walter Isaacson and Jim Kelly, who would become managing editors at Time; Graydon Carter, who would eventually run Vanity Fair; Kurt Andersen, who would head New York Magazine for a time (and now writes a column for it); Maureen Dowd and Frank Rich, who would become New York Times columnists. For that generation, Time magazine was still the Camelot of American media. To its readers, Time was then what it had always been: a savvy expression of Middle American values—optimistic, middlebrow, reliable. When Kelly went on a reporting assignment to a small town in Kansas in 1982, Time was so powerful an icon that people asked him to autograph copies of the magazine. “I felt like a demigod,” he says.

Kelly is the one who brought Stengel into the fold at Time. The two attended Princeton University together in the mid-seventies and studied under John McPhee, the venerated New Yorker writer. When Stengel got his entry-level job in the early eighties, the reporting system was the same one established by Luce in the forties. There were some 40 staff writers at the magazine and nearly 100 correspondents in almost 30 bureaus around the world, each of whom filed reports to a news desk that distributed them to writers, who in turn crafted them into stories. Staffers spent late nights hunched over Selectric typewriters, padding the halls in stocking feet, eating catered dinners, and closing the magazine in the wee hours of Saturday morning—essentially living and working together in the wealthy Eden of Time Inc., where little expense was spared.

After the magazine closed for the week, they decamped in dial-a-cabs to the Hamptons, where Kelly, Stengel, and Isaacson rented a bungalow in Sag Harbor dubbed “the Mouse House” because the woman who owned it collected dozens of mouse figurines. On any given weekend, media luminaries-to-be like Michiko Kakutani and Alessandra Stanley of the Times, former New York columnist and TV screenwriter Lawrence O’Donnell, and Evan Thomas of Newsweek could be found bonding at the beach.

“Everybody at Time was so damned smart. We had a glorious time,” says Graydon Carter. “We got drunk constantly. We didn’t have any real adult responsibilities other than showing up at work. It was an amazing group, and we’re all still pretty much friends.” In fact, Carter still holds an annual dinner party for many of the people who worked for Time in those days.

Isaacson was the ringleader of the group, considered by everyone to be the man likely to lead Time someday. He never failed to attend the Saturday-morning media softball game, where he could rub elbows with Mort Zuckerman and Ken Auletta. When Isaacson eventually did become managing editor, he made Kelly his deputy (because, says Isaacson, Kelly made “the trains run on time”). But Isaacson was much closer to Stengel. Both had studied at Oxford as Rhodes scholars; both shared a taste for history and politics and a fascination with the Founding Fathers. Over the years, Isaacson became a mentor to Stengel.

Stengel and Kelly were close as well, until Kelly succeeded Isaacson as managing editor in 2001. The tensions emerged over the prestigious job of editing the “Nation” section. Behind the scenes, John Huey—then editorial director of Time Inc.—had decided that Stengel should rise in the masthead and encouraged him to pursue the position. But Kelly was reluctant to give it to him, according to an intimate, because he thought Stengel wasn’t managerially organized enough to oversee a ferocious presidential-election season. After a protracted search, Kelly eventually gave in but kept Stengel on a tight leash, micromanaging and rewriting him. Stengel chafed. Asked by another editor at the time how he coped with Kelly’s being his boss, Stengel said, “You just don’t be his friend anymore.”

Stengel had left Time on good terms at various intervals over the past 25 years—once to ghostwrite Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, another time to be a speechwriter for Bill Bradley. But when he quit in February 2004, it seemed like it might be for good. Stengel says he wanted to “run something,” and there was no clear path for him at Time to do that. Kelly had selected Steve Koepp as his deputy managing editor, and Stengel reported not to Kelly but to executive editor Priscilla Painton, two steps removed in the chain of command. So he packed up and moved to Philadelphia to become the CEO of the National Constitution Center, a nonprofit museum dedicated to the study of the Constitution, where he invited Isaacson to join its board of directors.

John Huey was not a part of the well-connected Time-magazine club. A former naval-intelligence officer from Atlanta with a feel for the flyover states (he co-wrote the autobiography of Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton and still commutes to Manhattan from South Carolina) and an indiscreet cutup once known for doing a James Brown impersonation given the right amount of bourbon, Huey runs straight against the tweedy Ivy League type. After an acclaimed run as managing editor of Time Inc.’s Fortune in the nineties, Huey had become the heir apparent for the top job: editor-in-chief of Time Inc. Moving to the executive floors in 2001, he developed a reputation for shaking up the old Luce culture—mainly by tossing out career editors at big magazines like Sports Illustrated and Entertainment Weekly. Huey famously overruled a longtime editor who thought putting George W. Bush on the cover of Time after September 11 was a bad idea, telling him, “What makes you think anyone gives a shit what you think?”

“A disturber of the peace,” says his friend Howell Raines, the deposed editor of the Times, but “a more agile one than I was.”

The place where Huey most wanted to shake things up was Time magazine. And although he was already functionally running the company as editorial director, Time was the domain where his boss, editor-in-chief Norman Pearlstine, gave him the least authority. It was a source of constant frustration. In the fall of 2005, as Pearlstine retired and Huey prepared to become the sixth editor-in-chief, he told a colleague, “I can’t wait to blow up Time magazine.” He was finally going to get the chance to make his mark on the flagship publication.

It didn’t take long. On the last day of November 2005, Huey took Jim Kelly out to lunch and told him he was going to hire a new editor to run Time. Kelly would get a job “upstairs,” in the corporate offices on the 34th floor. Given that rumors of Kelly’s imminent firing by Huey had been rampant since Huey became editorial director under Pearlstine, Kelly wasn’t surprised. But he wasn’t happy either. Kelly had spent every day of his career at Time and had run the magazine for five years, managing it through 9/11 and Katrina and earning four National Magazine Awards. He was fiercely protective of the magazine, and had a complicated and wary relationship with both Pearlstine and Huey over their meddling.

Huey disregarded any succession ideas Kelly might have had and told him he would be hiring outside the company—automatically discounting at least three masthead editors who wanted the job. He did, however, ask Kelly what kind of editor he might choose. Kelly said somebody with an even temperament.

“You mean not an asshole?” asked Huey.

“Yes, not an asshole,” replied Kelly.

Huey first offered the job to Daniel Okrent, editor of Life magazine in the nineties, the first public editor of the New York Times, and now a popular historian. An amiable, silver-haired 58-year-old, Okrent has a sharp eye for the internal goings-on at Time Inc. He and Huey have been close since the nineties, when Huey was at Fortune. Huey says he offered Okrent the job on a limited basis—a one-year tenure during which they would seek a permanent replacement for Kelly. Okrent turned him down. (Because, he says, he didn’t want to disrupt his laid-back writer’s life, which includes five months a year on Cape Cod.) But he did agree to take on a short-term consulting job helping Huey find a new managing editor.

With Okrent as his consigliere, Huey spent the next few months meeting with friends and business executives around the country, hashing out ideas with current and former Time Inc. people like Isaacson, Time political writer Joe Klein, and former Fortune managing editor Eric Pooley. Huey wasn’t discreet about the search, and names leaked to the press: Newsweek editor Jon Meacham, Slate editor Jacob Weisberg, and former Vanity Fair and New Yorker editor Tina Brown. The speculation caused anxiety among the Time staff, especially the prospect of Time’s being run by Brown, who, according to a source familiar with the matter, volunteered herself for the job.

Huey says Stengel was always on a private list he kept in his calendar book, but his name didn’t come up in earnest until March 2006, at least three months into the search.

In four conversations—one with Okrent at Le Bernardin—Stengel and Huey formed a connection over their mutual frustration with the pace of change at Kelly’s Time magazine, in particular the failure of Time .com to compete with online news competitors. (Stengel briefly ran Time.com in 1999.) Stengel laid out his case in a seven-page memo titled “The Overarching Question and the Answer”: “Does Time still matter? Is there a place for a weekly newsmagazine in the 21st century?” it asked. “In this teeming media forest, this buzzing, blooming confusion of modern media, there’s a need for a single iconic publication … It’s not unlike what Luce founded in the first place, a kind of news handbook that is a guide for people. Everything else out there is undigested information. Time is knowledge,” Stengel wrote. He then listed the following columns:

Other News Media

Information

Clutter

Opinion

Time

Knowledge

Clarity

Authority

Neither Stengel nor Huey told Kelly that Stengel was in contention for the job, although Kelly heard about it through other channels. When Huey finally told Kelly he had picked someone in April, he said simply, “It’s not an asshole.”

Huey didn’t choose a firebrand; in some ways it would have been easier for Kelly if he had. He had chosen another member of the club, Kelly’s friend and implicit rival. The decision couldn’t help but seem like a personal rebuke, but at the same time it was a relative show of respect for Time’s cultural traditions. After an exhaustive search, Huey had emerged not with a bold outsider with revolutionary ideas but with a reverent Time insider. As Stengel himself says, “I’m radical, but I’m not that radical.”

By the time of Stengel’s hiring, Huey must have realized that “blowing up” Time magazine was going to be tricky. He was finally at the top of one of the great American publishing companies, but he was beset by corporate intrigue and an especially difficult business climate. The entire industry was in a tailspin, and Time Inc.—with 23 percent of industry ad spending—was losing advertising to the Web. Layoffs were becoming a painful annual rite. And Huey’s boss, CEO Ann Moore, was under intense pressure to cut costs.

By all accounts, Huey had an uncomfortable relationship with Moore when he took the job. He was the defender of the old journalistic tradition at Time Inc., and she was known as the “Launch Queen” for creating the softer titles that have fundamentally transformed the identity of the company. A former president of the People-magazine division at Time Inc., Moore oversaw the creation of In Style and Real Simple. Perhaps predictably, she has become unpopular among staffers at the legacy publications like Time and Fortune, who believe she tends to favor her magazines in the corporate turf wars that invariably arise inside Time Inc. Even Huey was given to occasional griping about Moore behind the scenes, according to several people who know him (he denies it), in part to show his allegiance to the hardened reporters of the company. He proudly announced, for instance, that he doesn’t read Time Inc.’s women’s magazines, over which he also presides.

Whether Huey read them or not, Moore’s magazines were driving the profits of the company. People alone constitutes close to 40 percent of Time Inc.’s profit. By contrast, Time magazine brings in just 5 percent. And its profits, while still strong compared with most magazines, were on the wane. At the top of the dot-com boom, 1999, Time made about $95 million in worldwide profit; last year, it made about $50 million.

What’s more, the allies Huey had once had in the Time Inc. corporate hierarchy were gone. The former Time Inc. CEO and Alabama native Don Logan, who was Huey’s bass-fishing buddy, had retired from the upper ranks of Time Warner. Pearlstine, who helped Huey rise to the top of Time Inc., had left for a private-equity job. And just before Huey took over as editor-in-chief, Moore pushed out three of his remaining friends—Time Inc. vice-president Richard Atkinson, Time magazine’s president, Eileen Naughton, and the popular head of Time Inc.’s advertising sales, Jack Haire—in a sweeping set of layoffs meant to quickly balance the books. Huey was shocked and angry—and suddenly isolated. “This is war,” he declared to a friend, in his usual bombastic style.

“It was a tough personal thing, but this is business,” Huey says now, growing moody when I bring up the firings. He says he and Moore “had a frank and open discussion of those issues, and I also expressed my total recognition that these were her decisions and she has to do what she has to do.”

The colleagues Huey had left on the 34th floor weren’t his natural buddies: Moore herself and the new co-COO overseeing the magazines Huey cared about, John Squires, a reserved business executive from Idaho. “This is not a partnership he would have chosen,” says a friend of his. “He has no choice. He knows that.”

Looking on the bright side, Huey says the whole affair actually made things easier. Now there were fewer people to argue with over the changes to come at Time, even if there was no one left to watch his back either. “There had never been that unanimity on that before,” says Huey. “It was more complicated for a variety of reasons, and now it was pretty simple.”

What was simple was that something had to be done about Time. Huey and Moore both saw the problem coming. Time had long depended on a “rate base”—the number of copies Time tells advertisers it puts in readers’ hands—of about 4 million copies. Former CEO Don Logan, who made Time Inc. enormously profitable during the nineties, had told Time-magazine publishers to always protect that base, because it gave Time enormous advantage over Newsweek’s smaller circulation of 3.1 million.

But in the declining ad markets after 9/11, advertisers began scrutinizing the numbers and questioning whether all 4 million of those magazines were really being read, since many thousands of them were given away for free. As Time’s traditional advertisers—especially Detroit automakers—began pulling back on spending, it became increasingly difficult for the magazine to justify its rate base.

So Time decided to do something rare in the publishing industry: drop almost a fifth of its readers. That in turn set off a number of fairly drastic changes. The advertising revenue lost by shrinking the rate base from 4 million to 3.25 million would have to come from raising the price of newsstand copies by $1 and cutting editorial staff from the masthead. To meet cost-cutting targets issued by Moore, Huey hired McKinsey & Company this past fall to examine the editorial operations of Time Inc. so Huey could execute a mass firing earlier this year. The bloodletting eliminated some 50 people at Time, which saved the magazine about $6 million (though the company had hoped for more).

The cutbacks have clearly taken their toll on Huey. In early February, when he attended a meeting with the heads of other divisions of Time Inc., he was stunned to find that many other departments in the company hadn’t met their cost-cutting targets. According to people familiar with the scene, Huey grew red-faced and went into an emotional tirade, angry that he’d fulfilled his financial mandate but others hadn’t. “He was venting and screaming,” says a source. “He felt betrayed. He trusted that everybody was going to do what they said.”

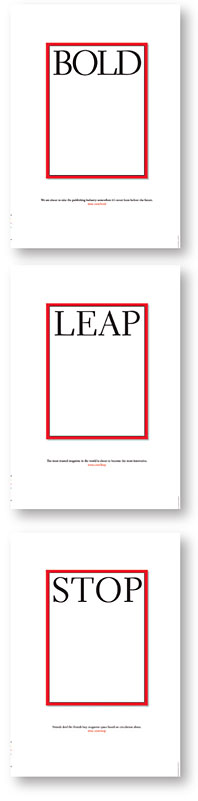

With pressure on the circulation front, advertising pages stagnant, and more cost cuts on the horizon, Time was going to have to make a leap to another business model altogether—a version of Time that could do a lot more with a lot less. It was not so much the blowing up that Huey had envisioned as it was a cutting back. Though that’s not how it was sold to the publishing community. Ads that ran in the Times and trade magazines touted a coming revolution: “We are about to take the publishing industry somewhere it’s never been before: the future,” read one ad. “The most trusted magazine in the world is about to become the most innovative,” said another.

The revolution is essentially a two-part strategy: Huey and Squires agreed that the first thing to be done was to change the delivery date for Time. The magazine’s own internal research showed that people were more willing to read news in print on the weekends, after they’d trolled the Web for headlines all week. “That means you close the magazine in the middle of the week, and you’re giving up this idea of ‘There was a week, it had news, and here’s what it was,’ and it becomes more of something you do—more forward-looking, more contextual analysis,” says Huey.

Part two of the strategy—a natural outgrowth of part one—would be to focus on developing Time.com. “Time has millions of happy customers who pay to read it, and we need to keep those people happy,” says Huey. “But we also need to face the reality that people get their information in a lot of different ways now. When we break news, we need to break it on the Web and we need to get people used to going to it.”

The Web, of course, is where the entire news industry is looking for salvation. But Time has been slow to get off the starting line. Currently, Time.com attracts half as many visitors as its competitor Newsweek .com. Stengel’s missionary zeal for the Web was one of the principal reasons he was hired. To turn the site around, he’s put in place Josh Tyrangiel, a 34-year-old writer and editor at Time who was hired by Isaacson and wrote music reviews when Stengel ran the “Arts” section in 2000. Tyrangiel is caffeinated, fast-talking, and rarely blinks. “We need to set a course,” he says. “And the course is 24-hour news for smart people. It’s about saving people time by not burying them with information they don’t need. It’s about using the curatorial and the editorial things that have been in place at this magazine for 84 years.” Pause. “Eighty-three years? Years.

“I’m not a patient guy,” he adds. “I’m in the mood to get moving, and a lot of other people are, too.”

While it is hard to argue with shifting resources online, there is no assurance that Time.com will ever be able to sustain the version of Time that exists today. As it stands, the Web brings in just a fraction of Time’s revenue—enough to pay for a few columnists and some bloggers but certainly not a whole news organization.

In fact, no one knows if any of this will work. In preemptively changing its print strategy, Time executives like to think they’re making a quantum leap past arch-rival Newsweek, strategically isolating it as an old-line Monday news read. And perhaps they have. But it might not be enough.

“They’re fighting a rearguard action, but that’s how you lose wars,” says Mark Edmiston, the former Newsweek executive who is now managing director of AdMedia Partners. “All you can do is push away the day when the reckoning occurs.”

Then there’s the question of what sort of magazine Time becomes after the revolution. There is some confusion on this point. Over a glass of wine at Palio Bar on 51st Street, Stengel asks me to guess what the most profitable newsmagazine in the world is. The answer, he says, is The Economist.

A magazine of news analysis and intelligent opinion with a clean, easy design, The Economist is a model Stengel admires and wants to inform the new Time. Of course, The Economist has only about half a million readers in the U.S., and Time needs about a couple of million more readers than that to keep its profit margin up, assuming it’s not going to charge big money for a yearly subscription. (The Economist charges about $100 for a yearly subscription to Time’s $30.) And one can’t help but wonder if The Economist isn’t too highbrow for a Time reader sitting in the doctor’s office.

Stengel says he doesn’t want to dumb down Time on the presumption that people don’t like a smart magazine.

But what, I ask him, about the infamous editorial maxim, “Put the food down where the dog can eat it”?

“Whose line is that?” he asks.

John Huey’s, I tell him. It’s a legendary Huey line that has been kicking around Time Inc. for years.

Stengel has never heard it before.

Later, when I ask John Huey about The Economist comparison, he rejects it entirely. “If we aim it at The Economist audience, we’re going to be a lot smaller,” he says. “Well, that’s not the magazine we’re making. To say that we’re going down that road is not where we’re going.”

Stengel later amends his description: He didn’t mean Time would be smarter, just more “aspirational.” When I ask Stengel if he and Huey had discussed the “smart” point after I’d brought it up, he says, “I guess we talked about the ‘smarter’ argument. He’s a little sensitive about that. So many people in the media world equate smartness with a niche and dumbness with mass.”

“Mass class” is the needle-threading phrase Stengel has found to describe Time’s big, aspiring audience, which seems to mean a huge crowd of random middle-class people who are smart (but not too smart) and engaged (but not too engaged) and might buy a Toyota if they see an ad in Time—aspiring to be like readers of The Economist, but not so much that they’d subscribe to The Economist instead of Time.

Calibrating the message of what Time will be hasn’t been easy. At the alumni meeting, Stengel said, “The sense that Time originally had was it covered the waterfront. What we’re doing now is a little bit narrower.”

Despite Huey’s lip service to mass, Stengel has already given Time magazine a narrower and sharper editorial profile, with more covers about war and politics than usual and almost no pop culture (Anna Nicole Smith didn’t make the cut) or soft social reporting (like the ever-popular Jesus Christ covers). He has aggressively ramped up the opinion in Time, hiring established, brand-name white guys who telegraph wonkishness. There’s liberal columnist Michael Kinsley, Harvard history professor Niall Ferguson, Weekly Standard editor William Kristol, and of course Walter Isaacson. (Five of the seven members of Stengel’s in-house advisory group—dubbed “the Magnificent Seven” by Stengel’s secretary—voted against hiring Isaacson, according to people familiar with the matter. Stengel said, “I guess this is where I get to be managing editor,” and hired him anyway.) Time now reads more like Meet the Press in print, which is essentially what Stengel is striving for when he says he wants Time to “lead the conversation.”

The redesign, by former New York Magazine design director Luke Hayman for the design firm Pentagram, is scheduled to appear on newsstands March 16. It is also expected to signal a more serious magazine: sparer and less cluttered, with a smaller logo, heavier paper stock, and more use of black and white. “Classic,” says Stengel. There will be new sections reminiscent of older versions of Time (the front of the book, now called “Notebook,” will be rechristened “Briefing”) and a slew of new columns in what Stengel calls a “branded expertise mall,” including Joel Stein—“a god to people in their twenties and thirties,” says Stengel—on food and Samantha Power on foreign affairs.

The conundrum is this: Changing the formula risks alienating Time’s mass audience. But media is losing mass anyway, having slowly fragmented along social, political, and demographic lines over the past twenty years. Mass media like Time—along with network news—has faded in this environment because advertisers are following younger readers into niche media. Time’s own media critic, James Poniewozik, declared “the end—or at least the extreme makeover—of the mass-media audience” in 2003 in a story titled “Has the Mainstream Run Dry?”

In a fragmented world where news junkies tend to break down along partisan lines, Stengel starts to sound like Barack Obama trying to hold the middle ground. “Our readers live in red and blue states, they’re Republican and Democrat, they’re rural and urban,” says Stengel. “We mirror the demographics of America as a whole. The New York Times talks to people who already agree with all the things in the New York Times. I would argue that the bar for us is higher because we have a diverse audience. We’re not preaching to the converted.”

Despite distancing Time from the Times, Stengel hasn’t been shy about trying to steal its columnists away, including his old friend Maureen Dowd and Times foreign-affairs columnist Thomas Friedman. He also tried to get Times legal reporter Adam Liptak and Peter Boyer of The New Yorker. Problem is, none of them wants to work for Time. “Are they waiting to see what I’m going to do?” he asks. “Absolutely they’re waiting. But as we go forward, I think some will.”

Few—perhaps not even Stengel himself—can clearly see the magazine that will emerge. In the recent round of layoffs, a large part of Time’s old reporting structure was eliminated. Today, in the southwest corner of the 24th floor, under a set of clocks representing different time zones, the news desk that once received 24-hour reports from around the world is all but gone. Many of the bureaus represented by the clocks—Los Angeles, Chicago, Paris—have either disappeared or been downsized. And some inside Time worry that Stengel’s plan to use “laptop journalists” to travel around to news events—the magazine still has 30 international correspondents—won’t be enough.

“When the shit hits the fan and New Orleans is washed away or a plane hits a building, Time’s always been able to rear up and do amazing work,” says one Time staffer. “Those have been the moments that really counted the most. Does Stengel still want to do that? He hasn’t been tested on that level.”

Stengel is being tested on a lot of levels now. This is the biggest job he has ever had, and in some ways he is still learning how to do it. In January, Time published an exclusive story on the new iPhone, in which writer Lev Grossman tweaked Apple CEO Steve Jobs about his secretive access to the product (“I don’t call Steve, Steve calls me”) and suggested that Apple had “some explaining” to do about backdated stock options. When the story hit the Web, Jobs called Stengel to complain (as it happens, Apple is a major advertiser in Time, and Jobs is a good friend of Huey’s). Stengel reacted by immediately excising the offending paragraphs from the Web (they have since been restored). Then he had Grossman come into the office to rewrite part of the piece for the print edition. Grossman was infuriated.

“I feel bad about the whole episode on both sides,” Stengel now says, explaining that the flap resulted from a miscommunication. “I’ll take the blame in the sense that there was an understanding that I had with Steve, which I did not tell the writer and that was an oversight on my part.” The backdated-stock-options part of the story wasn’t eliminated, he argues, just moved into a sidebar that ran in the magazine. Still, Stengel concedes that it was a weak moment for the magazine’s journalism. “Maybe a little bit,” he says.

Stengel has also drawn criticism for his selection of “You” as Time’s Person of the Year, depicted with a novelty mirror on the cover. He was roundly mocked on Comedy Central’s The Daily Show for his appearance on CNN to promote the issue. “[It’s] you!” announced Stengel, flashing the cover before American Morning host Soledad O’Brien. “You! Me! Everyone!”

Stengel claims it was good for the magazine. “I loved seeing myself on The Daily Show,” says Stengel. “I thought that was great. Was Time magazine talked about more than it’s been talked about in any way in a long time? Yes.”

Not in a good way, of course. The choice was widely perceived to be a mistake inside the magazine. “Well,” Stengel told one editor, “we’re only going to make it once.”

When I last see him, Stengel looks tired, with bags under his bloodshot eyes. Overseeing the layoffs, changing the delivery date and the design simultaneously, he says, “was like doing a triple half gainer and then having to smoke a pipe at the same time.”

The revolution has been hard on Huey too. “It’s not easy,” he says. “It’s not easy and it isn’t always fun.”

Having climbed to the pinnacles of their careers, neither seems to be exactly enjoying the experience. “At the moment, none of us are happy,” says Stengel. “It’s more fun when you’re in an era of plenty rather than an era of scarcity, when you’re starting magazines.”

The stakes are high for both Stengel and Huey. Inside Time Inc., there is speculation that with the leadership at Time Warner about to change in the next year or two—with CEO Richard Parsons stepping aside for president and COO Jeff Bewkes—the magazine company might be sold. (One somewhat far-fetched scenario has Norman Pearlstine making a run for it with the backing of investment company the Carlyle Group, where he is a senior media adviser.) Time Warner spokesperson Ed Adler gives assurances that “Time Inc. is not for sale. We’ve made a commitment to transition and grow the company.”

But the chances of a sale increase if Time Inc. can’t show profit growth quickly. A person who knows him says Huey thinks about the possibility of Time Inc.’s sale “every day.” It is a motivating force. Huey tells me that he has “no idea” if Time Inc. will be sold, but he hopes not. He and Ann Moore have found common ground in their desire to stay a part of Time Warner. “We think it’s the best for the people here,” he says. “We think it’s the best for the magazines.”

Whatever happens to Time magazine on his watch—whether it grows wildly successful or withers away—will be the thing he is remembered for. And Huey knows it. “Do I consider Time magazine to have an outsize importance to me and in some ways to this company? Yes,” he says.

“This is about Huey putting his stamp on the company and being seen as a bold leader,” says a Time Inc. editor. “And there’s nothing more important to John than being seen as bold.”

Huey shies away from talk of his legacy. “If you want somebody who has a legacy, Jann Wenner has a legacy, he started Rolling Stone. Ted Turner has a legacy, he started CNN. I don’t think people who pass through these jobs … ” he trails off. “Ex-CEOs don’t mean spit. And neither do ex-editors-in-chief. That’s just the way it is.”

But Henry Luce has a legacy. And if Huey needs any reminder he need only look around him: He sits in Luce’s old office, built in 1958. Though he won’t be there for long. In a highly symbolic turn of events, Time Inc. plans to relinquish its storied corporate offices on the 34th floor to investment firm Lehman Brothers. Renting out Luce’s old stomping ground is just another cost-cutting measure in the fight to save the company he founded.