In preparation for my move to Columbia County I sent an e-mail to friends. It had my new address and phone number, reassured them that while my new house didn’t have garbage pickup or mail delivery it did have running water, and tried to convey enthusiasm about my imminent move to the country. “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere!” I quipped, borrowing the line made famous by Frank Sinatra. It expressed cockiness, optimism, even a healthy dose of respect for the challenges awaiting me. It made me sound like I knew what I was doing. But I had been a city dweller for seventeen years, and underneath, I was scared as hell.

That first summer passed in a giddy haze. This is great!, I kept yelling at myself. Driving to the bank meant passing three farm stands. A traffic jam was more than two cars at an intersection. We’d bought a four-bedroom 1898 Victorian farmhouse on three-quarters of an acre, located on a quiet side street in a hamlet where the sum total of commercial offerings was a post office, a gas station, and a deli. It had an inground pool that was broken and full of frogs—their nighttime chorus was a welcome replacement for sirens and car alarms. My daughter quickly morphed into a nature child, running around the yard half-naked, catching baby frogs and naming them Buddy. I signed her up for swim classes at the lake at a cost of $20 per session—$2 per class! Our car-insurance premium dropped in half. Target was eighteen miles away, and it took exactly eighteen minutes to get there. My first favorite thing about upstate life was the math.

In retrospect, I can see that the downsides were there from the start. I just couldn’t acknowledge them. I was on a mission to acclimate, to assimilate, and in my driven, imported New York way, nothing was going to stop me. Our home was in an economically mixed neighborhood. The very first day, I marched my daughter up the street to a house where I’d seen kids playing. A passel of them tumbled around a yard strewn with bicycle parts and sun-faded toys. When they saw us, they fell silent and stared. I introduced my daughter, and an older boy offered to drive her around the yard in a red plastic motorized Jeep. She climbed in, and he careered around the yard, bashing into things and screaming at anyone who tried to climb in or displace him. I fought the urge to extract her, to discipline the kid’s reckless driving. After about fifteen minutes of this, she got out of the car and we thanked them and walked home.

The next day, they stood at the end of our driveway.

“How many people live in your house?” asked a girl.

“Three,” I said. “How many people live in your house?”

“Eleven,” she answered.

In the fall, I enrolled my daughter in a publicly funded preschool, a Head Start–like program that met five half-days per week. I chose it because all the private preschools met just three half-days per week. I got off to a bad start with the teacher. Maybe my helicopter parenting style rubbed her the wrong way, or maybe the fact that I showed up brandishing glowing reports from my daughter’s progressive nursery school seemed uppity. Whatever the reason, I had a hard time communicating with her. At the end of the first week, I asked how my daughter was doing. She shrugged, said, “Par for the course,” and walked away. I reeled. What did that mean? I asked for a conference and was blankly told, “We do conferences in January.”

I had better luck with the assistant teacher. She occasionally yelled at the kids and talked straight with the parents. It was from her that I learned my new social standing. I overheard her mention that she had New York weekenders living on her road. She said her husband called them “citiots.”

“Hey!” I protested. “I’m a citiot.”

Apparently, I was the only one at the preschool. Most of the parents either worked full-time or juggled several kids. One mom had, in addition to her 4-year-old, a 9-year-old and a 24-year-old. This was a form of upstate math I had more trouble grasping. I tried without luck to set up a few playdates. As the autumn stretched on, I grew increasingly isolated. My husband, a contractor, was still getting jobs in Hoboken and Jersey City. He’d leave the house Monday or Tuesday morning and return Thursday or Friday night. There was a playground down the street from us, but it was stocked with restless teens after school. People didn’t need playgrounds; they had their own damn swing sets. The weather was turning colder, anyway. I started to get a little desperate for friends.

STAGE 1

Feeling the urban squeeze.

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

I pinned my hopes on a dairy farmer with a son in the preschool. She was lean and kind of hot. She always showed up in work boots and dirt-smeared clothes, and she had gentle brown eyes. We took to chatting about the dairy business at pickup time. Finally, as Thanksgiving approached, I worked up my nerve.

“Could we visit the farm sometime?” I asked. “It’s so new for us, it would be really exciting.”

“Sure!” she said. “My son would like that.”

“Great!” I said. “How about next week?”

She thought a moment. “Well, deer season starts Monday, so it’s going to be hectic for a while.”

I felt myself deflating. “Why is that hectic?” I asked.

She turned those innocent eyes on me. “Because that’s when we get our meat,” she said.

My jaw dropped slightly open. “We freeze what we don’t use,” she elaborated. “We hardly ever buy meat at the supermarket.”

For the first time, I made myself confront the fact that in moving upstate, I had quite possibly done something stupid. The tremor of fear buried in my initial e-mail came a little closer to the surface. I was worried about myself. Maybe I wasn’t going to make it here, after all.

Then winter came.

New Yorkers’ striking out for the country is nothing new. Half the time, I discover that people I’ve assumed are locals just came here from the city a lot longer ago. My babysitter, a 2006 graduate of Kinderhook’s Ichabod Crane Senior High School, is the offspring of New Yorkers who arrived twenty years ago. A friend named Irene Mitchell got here in the mid-eighties—she grew up on Tompkins Square, living in an apartment inside the public library, where her father was the custodian. My husband and I hit it off with a plumber, only to discover his roots were in Union City. He and my husband stand around the kitchen swapping crazed-driving stories like college buddies.

But the new crop—those who’ve arrived in the past five to seven years—is different. We’re here because we couldn’t afford to stay. I did the math: My family had to move 135 miles from the city to get a four-bedroom house for under $200,000 in a district with decent public schools. Recent émigrés tend to be casualties of the real-estate boom, a weird spin on the white flight of the sixties: Instead of our rejecting the city, this time around the city rejected us. It flushed us out because we couldn’t keep up. It demanded more of us, in terms of our ambition and upward mobility and materialism, than we were willing to give. Maybe we owned an apartment, and it became worth so much money that we decided to cash out and grab a better life. Or maybe we missed the buying train altogether. Nick Raposo, a writer for children’s TV, and his wife, Ticky Kennedy, a stay-at-home mom with a Ph.D. in early-American literature from Yale, weren’t just squeezed out of the New York market—they were too poor for New Haven. They bought a mid-nineteenth-century farmhouse on seven acres in North Chatham, where they’re raising their three kids. “For the price of the farm, we could get a nice one-bedroom apartment in the middle East Side in, like, the Fifties,” he says. “Or a two-bedroom in one of those horrible college towers. I’m sorry—you don’t break your piggy bank for that.”

Heather Campbell, a marketing guru, and Jeff Andrews, an e-commerce manager, were “old-timers” in an East Village co-op building who grew dismayed as the neighborhood changed. “When we moved in, the building didn’t have a managing agent,” Heather says. “So we all did something. I was the treasurer—I paid the bills. We all knew each other and would hang out together. Now people don’t want to get involved.”

But Heather and Jeff’s disillusionment went beyond real estate. “I had my life perfectly planned up to the age of 35, and then I didn’t have anything planned after that,” she says. “I had everything I desired, and then all of sudden, I was like, ‘Oh, I did it. And actually I don’t like where I am.’ New York just wasn’t the same anymore. You get into this cycle where you have to keep this job you hate because that’s the only way you can afford the apartment you love. You’ve bought a place, you’ve got a mortgage payment—you can’t all of a sudden decide to change careers and start making $17,000 a year again. It got to the point where the sacrifices we were making in order to be able to live there negated the purpose of being there.”

Opting for the rural release.

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

On top of that, Heather and Jeff had decided not to have children. As more and more of their friends disappeared into parenthood, they found themselves the odd couple out. Hudson, with its walking-distance bars and gay population, glittered like a backwoods disco. So they sold their co-op and bought a 5,600-square-foot pink mansion on Hudson’s main drag, Warren Street, for $370,000 in the fall of 2005 (“The peak of the market,” Heather says ruefully). And they love it. “I think we have more of a social life here than we did in the East Village,” Jeff says.

Upstate lures parents, too. It’s a magnet for high-achieving women who’ve decided that their best expression of feminism is to stay home with their kids. “I think it would have been hard to be an at-home mom in New York,” says Ticky Kennedy. “That would have been really stressful. So many fewer people are doing it there. Here, a lot of people are doing it. So it feels easier.”

As an at-home mom myself, I spent my first year here in a constant state of disorientation: too New York for the country, too country for New York. I’d revel in the less competitive atmosphere for my daughter, then gape in disapproving disbelief at the unsupervised kids pedaling bikes without helmets and the McDonald’s bags on the floors of classmates’ cars. I wanted to fit in, yet I refused to set foot inside Wal-Mart. What I’d taken for granted in the city was my innate ability to sort through the vast pool of humanity in my own neighborhood and zoom in on the strangers who seemed compatible and appealing: I’d strike up a chat with a mother, and within moments find out that, like me, she was an arts-related professional taking time off to raise her kid(s). I missed that easy camaraderie.

Meeting other transplants doesn’t always solve this dilemma. Yes, we share a city background—but it’s not necessarily the same city background. If there’s another Maxwell’s-graduate indie-rock chick north of the county line, I’ve yet to meet her. “I never had trouble making friends in the city, and I do have trouble here,” admits Elizabeth Powell, a leather-goods designer who moved to Claverack in 2004. “I feel like I haven’t found a niche.”

My first winter in Columbia County, I tasted madness. Snow shoveling was a four-hour ordeal. It was like I’d missed the memo. I didn’t have the right equipment, or I’d get the timing wrong. During one storm, I shoveled too early, and more snow fell, then thawed, then refroze overnight, creating a two-inch slick of ice on my driveway. I ended up chasing a plow guy down the street. Or I’d shovel too late, and the snow would get too heavy to lift. This is what it’s like working on a chain gang, I remember thinking.

With my husband gone most of the week, my daughter and I spent long hours together. Sometimes, I’d get hinky from operating on her mental level all day. One night, my husband called from a family gathering in Fort Lee. Happy humans chatted and chortled in the background. I could practically smell the pot roast. I whined about some random incident of the day. “Look, I’ve gotta go eat,” my husband said. “Don’t you hang up the phone!” I screamed. “You’re the first adult I’ve talked to all day!” At nights, after my daughter went to bed, I’d try to knock out some freelance work. One evening, I was trying to review a three-CD Nick Cave collection. It should have been easy—I’d been a fan for twenty years. Maybe that was the problem. I kept reflecting back on my carefree, beer-soaked indie-rock days. I remembered seeing Cave at the old Ritz on 11th Street. I was so psyched that I crawled out onto a girder holding up the balcony, just to be closer to the stage.

Now here I was, stuck in a dark, chilly, empty house. Outside, the wind howled. Moonlight reflected creepily off the snow. On the main road a quarter of a mile away, a lone car’s headlights flatlined across the window.

In a fit of defiance, or maybe just desperation, I grabbed a composition book and started sketching. I drew my desk, my computer, my pencil box. Then I drew my Frank Sinatra poster. Then, feeling oddly energized, I drew myself. I’d never thought much of my artistic abilities, but it felt good, just moving the pencil across the paper. I had a new purpose in life. The whole rest of the week I was preoccupied with sketching. I felt as though I’d liberated some long-repressed facet of my creative being. When my husband returned home, I displayed my accomplishments. He glanced at them quickly, then laughed. “These look like they were done by someone in an insane asylum,” he said.

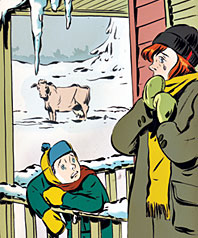

Discovering the rural reality.

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

If I’d known about all the other New Yorkers hunkered down nearby, I’d have felt better. I’d have realized my experiences weren’t unique. Hell, they weren’t even that bad. Sue Dixon, who moved to Columbia County four years ago, remembers her first winter. “When we moved here, it was February,” she says. “Which I thought was the tail end of winter, because I’m a California native. The day we arrived, it was beautiful. Then my husband went back to work, so I was here by myself. Two days after he left—blizzard. I had never shoveled snow in my life. I remember not even knowing where to begin. I didn’t have the wardrobe. I had my sneakers on. I would be outside for ten minutes, and I would be soaking wet. The tide had turned. It had gone from ‘Oh, everything’s going to be so wonderful and so amazing’ to ‘I hate this place with a passion.’ ”

Nick Raposo and Ticky Kennedy’s first winter was equally rough. “We were constantly hearing that it was the worst winter since, like, 1820,” says Ticky. “There was basically no school. We put our garbage out in December and didn’t see it again until April. It was unbelievable. And very cold too. You really couldn’t go outside. People walked around pale. Shell-shocked, stumbling around—like rickets. Scurvy.”

Megan Kane and Zohar Lazar, Brooklynites who relocated to an eighteenth-century brick house in Kinderhook, unwittingly chose the winter to renovate their third floor. “We had no roof on our house,” she says. “The average temperature that year was three or four degrees.”

“Our bathroom was this makeshift shower they put up for us,” says Zohar. “We could see the stars at night. We had a little heater—some sort of heater mounted on top of a barbecue propane tank. It reflected the heat forward. So if you were directly in front of it, you were burning, but if you stepped one foot to the side, you were freezing. It was very quick showers.”

Even mild winters can be difficult. Heather and Jeff’s Hudson mansion had been vacant for several years before they bought it. The first couple of months, they came up only on weekends. “Not only did we not have a furnace or any heat, we also didn’t have any running water, including a toilet,” says Heather.

“What did you do?” I asked. “Dig a hole in the yard?”

“You do three things,” says Heather. “You learn every public restroom in the area, and you schedule your errands around when you have to go. And then you buy camping supplies for the middle of the night. And then your nice neighbors let you use their bathroom.”

Coping with upstate contractors is no mean feat. “We had no hot water,” Nick Raposo recalls. “In the city, if you don’t have hot water, you call the super and the super takes care of it. Here, I called the company that had been doing our heat. I’m like, ‘When can you get here?’ They’re like, ‘There’s nobody here this weekend.’ We didn’t have hot water for four days. In the city, if there’s no hot water for a day, the entire building goes into revolt.”

There’s also the critical question of how to make a living. Well-paying jobs are scarce, forcing many people to endure long commutes back to the city they were hoping to leave behind. Sue Dixon happily gave up her career in interior decorating to devote herself to raising her daughter, but her husband, Bob Candeloro, couldn’t cut the money cord. So he makes a daily commute on the train from Hudson to his banking job in the city. It’s three hours door-to-door each way. “The first couple of years, he was staying down there part time, but it just didn’t work for us as a family,” she says. “So in the morning, the buzzer goes off at 4:15 and he gets on the train. That train, no one’s working. Everyone falls asleep. You will be thrown off if you dare turn on a light. For a while, he was taking the 7:10 train at night. To get home at ten, and unwind for an hour, and then to get up at four—it’s crazy. I’ve been reaping the benefits of living this very simple life. Bob has not.”

Heather and Jeff have a novel approach to making a living upstate: They don’t. They’re renovating their house themselves, with the idea of selling it and starting another rehab. Or maybe they’ll stay in the building and open a store on the ground floor. “Not a vanity shop, like, ‘Oh, I always wanted to do this,’ ” Heather points out. “We want to create a business the community needs.”

But that’s years away. Right now, they barely have a working kitchen. “In the beginning, we ate out a lot,” Heather says. “I was thinking I would have an ongoing consulting stream, but we eventually decided it wasn’t worth it. So that required tightening our budget a little bit. The one thing we had was a panini maker. People would invite us over for dinner, then we’d feel obligated to invite them back. So we’d invite them over for paninis. That’s pretty much all we ate all winter.”

The mansion is job, child, and parent. It’s the mother of all home renovations: a three-story warren of raw walls, exposed ceilings, peeling paint, and loose wires. The second time I visit, on a weekday evening, the house is dark and I wonder if I’ve mixed up the date. But Heather and Jeff answer the door and explain that, since my first visit, several rooms have lost electricity. “We went out to dinner, came back, and none of the lights on the second floor worked,” Jeff explains. “We traced it to a junction box, and the little cap on the thing had actually fried. Melted. I’d never seen that before.”

“How long ago was this?” I ask, expecting they’ll say last weekend.

“Oh, about a month ago,” says Jeff.

Flashlight in hand, they lead me through front and back parlors, through side porches and sun porches, and many bedrooms. “We have periods where we walk around trying to find each other,” Heather says. “ ‘Hello! Hello!’ ‘Where are you?’ ‘On the staircase!’ ‘Which staircase?’ ”

In one room, tangled clumps of wiring hang between studs like strands of matted hair. Back downstairs, we arrive at central command, a room they call Germany.

“Why do you call it Germany?” I ask, the straight man in their absurdist comedy troupe.

“This Old House suggests that you set up a room that’s very organized with all your tools,” says Jeff. “They call it Germany.”

“And you set up a room that you don’t do any work in,” adds Heather. “They call that Switzerland.”

“Our Switzerland is in heavy retreat,” says Jeff.

“Switzerland is losing the battle,” agrees Heather.

I’m starting to love these people. They’re way more insane than I am. I glance at Germany’s ceiling and notice that it’s coming apart. Flimsy acoustic tiles, dating from an era of cheapo redos, dangle in midair. “One started to come down,” Heather explains, “and then Jeff started to take a little bit more of it down, and that involved large portions raining down.”

“So watch your head,” says Jeff.

I’ve lived through permutations of each of these challenges myself. My husband and I are doing the This Old House thing; for months, I washed my hair beneath a copper pipe sticking out of an unfinished wall. We’ve had the work drama—my husband’s still trying to establish himself upstate as a contractor, competing against better-entrenched locals and equally eager artisan-handymen transplants. We’ve had possums in the yard, randy cats in the garage, and a spider bigger than my fist in the kitchen sink. (My husband, in Jersey at the time, coached me over the phone: “Cover it with a dish towel, mash it with a potato masher, and throw the whole mess in the garbage.”)

Yet, for me, all of these issues pale in comparison to the central issue of assimilation. I can deal with bugs, a barn that a strong gust of wind could knock over, and even subzero temperatures, but the neurotic city achiever in me can’t stand to be unloved, misunderstood, or ignored. A remark made by a former New Yorker, the friend of a friend, recently found its way to me. She was discussing her decision to pursue options other than public school. “I visited the public school,” she said, “and I looked around and I thought, I just can’t assimilate.”

Like her, I’ve never had to assimilate before. I’m white, educated, and reasonably secure. The question of assimilation is even more acute for Elizabeth Powell and her husband, Eliel Mamousette, a multiracial couple with three young children. Columbia County is infamously monochromatic, unless you wander away from Hudson’s antiques district into a disturbingly segregated area of minority poverty. “I find it difficult, thinking about our kids,” says Elizabeth. “Everything I hear and read is that children of mixed race tend to consider themselves black. So how would we explain that disparity in Hudson?”

Reminding yourself why you moved in the first place.

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

Eliel—another commuter; he works in the Manhattan district attorney’s office—wonders whether he wants to sentence his children to an upbringing of standing out. “My parents moved here from Haiti,” he says. “We ended up in a lower-middle-class neighborhood in Spring Valley. Spring Valley being a bedroom community, it had a very wealthy middle class also, so it had a great public-school system. But the people who lived in my apartment complex were all black. I went to school and got tracked, and all of my classmates were white. So I’ve always had that experience in my life. I survived it, but when I think about the children, I start thinking, How will they define themselves?”

I try to remind myself that upstate-downstate prejudice goes both ways. As city people, we’re just as guilty of making generalizations about the kinds of people we meet up here and leaping to flawed conclusions. “We had an intern working for us, a girl from the local school who goes to one of the local churches,” says Kelley Drahushuk, a co-owner of the Spotty Dog, a Hudson bookstore and microbeer bar. “She was saying, ‘I don’t like gay men because they take away men from women who need good men.’ ”

I’m appalled. “That’s just ignorant,” I say.

But Kelley’s partner, Alan Coon, is appalled at me. “I’m not going to judge the way she was brought up,” he says. “She’s a terrific girl, and she was getting straight A’s in high school. I would never call her ignorant.”

“Her reality is just different than my reality,” says Kelley.

Sometimes living upstate is like being on a liberal-conservative talk-show panel, only instead of yelling at each other, we’re supposed to listen and actually learn from our differences. Moreover, I’ve discovered that despite the lack of racial diversity, Columbia County is hardly a monoculture. The term locals should be recognized as the vague slur that it is and dispensed with altogether. I’ve met non-city people who are better educated, more liberal, and more affluent than me. Others serve the community in ways that put me to shame—as firefighters, church volunteers, peace activists. And contrary to my New York friends’ dire warning, there are plenty of Democrats—our district just threw out a Republican incumbent and elected freshman congresswoman Kirsten Gillibrand. I’ve met longtime residents involved in alternative energy, water conservation, and open-space initiatives. Transplants don’t corner the market on giving a hoot.

Recently, I’ve been feeling hopeful about my prospects here. It occurred to me that someday, the newcomers will become old-timers. We’ll settle in and wreak subtle changes on the landscape and the population—one hopes progressive changes and for the better. Some of us may turn tail and run, but others are in it for the long haul. Sue Dixon got over her initial trauma. In 2004, she founded Dancing Moon Playhouse, a children’s art, music, and theater space in Ghent. Two years later, the town gave her the boot after serving her with code violations. Her idealism is undiminished. She envisions selling her current house, buying a new one, and building a three-story barn to house a bigger, more ambitious Dancing Moon, one that will offer “a great camp, outdoor space, and a gardening program.” “I love it so much,” she says. “It’s been a magical place for me.”

I wouldn’t get quite that dewy, but over the past several months, I have started to feel a lot better. After that initial adjustment period, I settled on a formula for making my new life more manageable. (1) Make frequent weekend trips downstate to visit family and friends. (2) Schedule those trips around stock-up sessions at Trader Joe’s. (3) Don’t try so hard to fit in. It’s not like I think I’m ever going to turn into a “country” person, but I did, after about a year, wake up to the notion that I needed to stay the same freak I’d always been and let the people around me take or leave it. On the upside, I’ve decided that my cultural interests could use a little broadening beyond the Guided by Voices catalogue. I’m rediscovering poetry, getting out to local galleries, and generally working harder to meet halfway the much wider variety of reference points I encounter. When I tell my upstate friend Donna that I have a crush on Pete Yorn, and she responds by telling me about the Styx, Journey, and REO Speedwagon triple bill she saw with her husband in Albany, I don’t panic—I get inspired. I slip her 6-year-old a CD of our family favorites, like “TKO,” by Le Tigre, and “Bathtime in Clerkenwell,” by the Real Tuesday Weld.

Around the time of my first anniversary here, the assimilation gods gave me a pat on the head. At the end of my daughter’s preschool year, the teachers staged a graduation ceremony. After giving diplomas to each of the kids, they handed out a few awards to parents. As one of the only at-home moms in the class, I’d ended up ferrying around kids who needed rides while their parents were working. The head teacher, the one who I thought didn’t like me, stood in front of the group.

“And the schlepper award goes to … Mrs. Salzberg!”

I stood up, beet red, and walked to the front of the room. The whole place burst into applause—all these people who I figured didn’t even know my name. Well, actually, they didn’t know my name. They assumed I had my husband’s last name. But that was okay. The teacher beamed and handed me a little plant.

I couldn’t have felt more proud if I’d won an Academy Award. I’d made it in the country. Barely.