Morning breaks, and yellow school buses pull up outside the Corinthian portico of the Tweed Courthouse, the city Department of Education’s stately repurposed office building. For four-plus years, charter schools have been Chancellor Joel Klein’s most pampered pet cause. And now, after considerable hoo-ha in the press, a unique and controversial example of the genre had unpacked itself in his own ground floor.

Even for a charter school, the Ross Global Academy has an unusual—even loopy—vision: a Metropolitan Museum ambience wreathed with the joss-stick smoke of the New Age movement. “Educating the whole child for the whole world” is how the school frames its quest to turn its charges into global citizens of the 21st century. Ross Global’s recruitment material woos inner-city parents with talk of ancient civilizations, prophetic movements, and Ayurvedic nutrition. The curriculum is accessorized in the classroom with reproduction art: a discus thrower frozen in alabaster at the exact moment of achieving rhythmos in one corner, the lopped stone head of a Cambodian deity up on a shelf with the textbooks. A Ross Global student might read the Popol Vuh of the Jaguar Priests in English class, explore ancient Sumer via cuneiform tablets. A Ross Global student should not only ace the standardized tests blindfolded but also be able to compare Greek theater with Chinese opera. The children blog about organic produce. Instead of gym, there’s wellness.

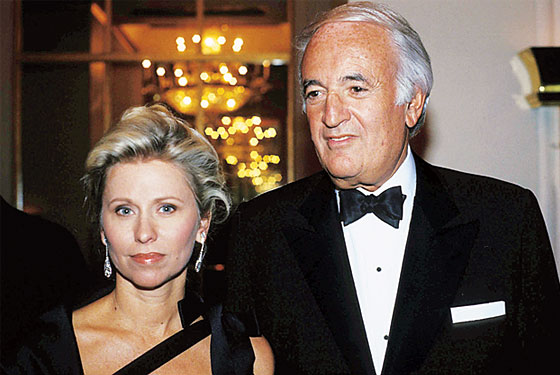

That is the idea, anyway, as sold to the city by Ross Global’s birth mother, Courtney Ross, the former gallery girl, documentary filmmaker, and interior decorator who is the latest edupreneur aiming to crack the urban-education conundrum. Mrs. Ross (as she prefers to be called) is the widow of Steve Ross, a man who dreamed globally, balloon-twisting a family funeral-parlor business into the Time Warner empire. A beloved boss, generous to distraction, he died in 1992 of prostate cancer, just as his wife had started homeschooling their only daughter, Nicole, an experience stretched to almost comic overadequacy by field trips to history-book locations all over the globe, instruction in the various social graces, and ad hoc seminars on art appreciation at her Park Avenue apartment. It wasn’t long before Mrs. Ross realized that schools could elevate her to a larger cultural governance. Sixteen years later, her East Hampton–based enterprise, now called the Ross School, has expanded into something of a Taliesin East, with a carefully pruned student body that has now graduated more than 200, some to schools like Brown and Yale.

But caring for a squalling-baby New York City public school like Ross Global Academy—its students essentially picked out of a hat—is a very different kind of challenge. By all accounts, it’s been a difficult gestation, made more so by what some might call the imperious ways of the institution’s own high priestess. Mrs. Ross has occasionally flashed her vengeful Kali side, wearing a garland of severed heads and holding a bloodied sword. By this past November, both the principal and the president at Mrs. Ross’s charter school had quietly vanished. In February, another principal went up in a puff of smoke after just a couple of weeks bobbing around the premises. The “ ‘chaos’ of a school evolving around its students helps them become poised for a world of constant change” is a tenet of Mrs. Ross’s philosophy.

Certainly, these were not the best of omens. But amid the chaos of Ross Global’s first months, Mrs. Ross was forging ahead. Out in the Hamptons, the very bosom of Mrs. Ross’s enterprise, the moms and dads of the East End gathered in December in the Ross School’s Center for Well Being, where her fourth annual Starlight Ball was just starting to jam. Flashbulb pops signaled that Mrs. Ross, their Texas-bred founder, the benefactor, as they often call her in conversation, was inside the perimeter.

The Ross School on the South Fork is the prototype Mrs. Ross hopes to photocopy into something of an empire. Out here, Ross is the only game in town, as far as private high school goes, for those who don’t want to go parochial or—Lordy mercy—public. Over the years, the Ross School has become the subject of obsessive Hamptons gossip. Some observed what was happening on East Hampton’s Goodfriend Drive and saw the cult of the Goddess! All shuffling about in those dress-code Japanese slippers! And in a sense, it was true—the Goddess has been at the core of Ross’s curriculum. Any Ross fifth-grader could tell you about the cult of the Goddess, identify the shift from the patriarchal society back to the matristic—it’s all there in the spinach-dip dialect of the course catalogue. Goddesses of all races, colors, and creeds were leading characters in the school’s mesmerizing spiral of cultural history, an innovative curriculum purporting to teach what was worth knowing—in order—since creation. On Charlie Rose one night, explaining her academy, Mrs. Ross thunked down a model of the spiral. It looked like something on the shelf in a gynecologist’s office. She called it “an artifact from our evolution.”

Though other women at the fund-raiser wore gowns, Mrs. Ross was festive-business in a glossy brown pantsuit, the smile warm and dimpled, and she had mastered the Clinton shake and shoulder grip. At 58 (she’s now 59), she was still a beauty, her face lacking the paint job that often comes with a decade’s redecorations.

They were all there to celebrate and support Ross’s glorious, whimsical homeschooling experiment that had evolved muscular legs. In 1991, the Ross School began as a tutorial service for Mrs. Ross’s daughter and her little friends. They wouldn’t just study the Great Wall of China—they would travel there. Its classroom consisted mainly of the passenger cabin of a Gulfstream, which was replaced within ten years by a compound of East Hampton buildings. Her project had become a swanky, architecturally significant ashram of higher learning out there in the woods.

But like any institution backed by a Carnegie or a Vanderbilt or a Rockefeller, the entire operation needed to be sustainable, like the organic food in the cafeteria that started a revolution in school dining nationwide and the Brazilian ipe paneling. A staggering philanthropy had been committed: To launch and support her school, Mrs. Ross had spent $330 million and counting, according to a board member. It was why she was presiding over this roundup of South Fork breeding pairs on a Saturday night in December, in a school gym surrendered to a klieg-light-trimmed chuppa and a creative caterer’s hoodoo.

And now: It was time to extend a very big welcome to “our visionary,” as Tim Kelley, the brand-new head of school, pleasingly described her. (There was usually a newish person in charge padding around, the ten-plus others having been discreetly dispatched by shining thunderbolt, gone for “personal reasons,” as it was sometimes gingerly phrased.)

“Look, what Courtney Ross has done here is pretty amazing,” says architect and Ross parent Daniel Rowen. “A lot of my clients are strong-willed people—Martha Stewart, Larry Gagosian, Ian Schrager. They’re not warm and cuddly, but maybe that’s not why they were put on this planet.”

And who among the local bien-pensants could question her commitment to educating the blacks and Latinos and Shinnecock Indians of the region? Every year, $1 million (or more) of her personal fortune is docked to pay financial aid for almost half her students. Of the first five graduating classes, 33 percent were the first in their families to enroll in college.

Husband Steve’s tan photo was a postage stamp in the Starlight Ball program. “Not much is known of Steve Ross’s interest in education,” Mrs. Ross rightly observed in her plucky newscaster voice. He was a financial savant who didn’t read books, say friends, recalling the phony gilded spines in the Potemkin bookcases lining the 10,000-square-foot Park Avenue double duplex he shared with Courtney, his third wife.

That December night, the Ross School was honoring one of the mothers of the Republic, Christie Brinkley, and the ex-model wept like Miss America when Mrs. Ross handed over some roses. Later, Brinkley’s daughter Alexa Ray Joel would sing. Among the community’s scarce winter homesteaders, the Brinkley-Cook-Joel clan is handled with care, like a nest of endangered piping plovers. “Attention press,” reads a handout. “Please do not approach or speak to Ms. Brinkley’s children. You are permitted to film or photograph Alexa Ray Joel’s first song only.”

Always exquisitely attuned to her image, tonight Mrs. Ross made sure she was photographed with a Somalian refugee she’d recruited from Ross’s sister school in Sweden.

Those who know her well see Ross’s admirable commitment to diversity as rooted in her own past. “Courtney has a real southern sensitivity to overcoming the stain of southern segregation,” says her longtime friend the Reverend Jesse Jackson.

Mrs. Ross’s hometown, Bryan, Texas, is still a small town, dominated by Texas A&M University nearby. Her grandfather George Stephan owned the local icehouse and Coca-Cola bottling franchise. And when George Stephan died, his daughter, Courtney’s stylish, attractive mother, Gloria, took over as president.

Courtney’s father, Elbert Sale, was winkingly called “Chic Sale,” old-timey slang for an outhouse—somebody might say, “I’m going to the chic sale”—and almost certainly a nickname bestowed when he was an A&M cadet. It was Chic, a good ol’ boy whose hands by the end of his days shook so bad he could hardly light his smokes, who put junk-food-vending machines in A&M’s dorms.

For Gloria to be a CEO, running the business and giving orders, was an anomaly in Bryan. “She didn’t mind telling it like it was, and she’d cuss a little bit,” says judge Tom McDonald, who grew up with Courtney and her two sisters. The Sales were one of the richest families in town, charter members of the Briarcrest Country Club. The girls were sent to Holton-Arms, a boarding school just outside Washington, D.C. Of the three downtown movie theaters in Bryan, the only one that admitted blacks had a “colored” balcony. Those cotton plantations out along the Brazos River drew migrant workers from Mexico, some of them almost pure Indian, who came down from the Sierra Madre. West of town was a great big messy labor camp.

“She came out of an apartheid culture,” Jackson says of Mrs. Ross, “and she chose to overcome it.”

Ross Global’s demurely Delphic motto could be the inscription over Mrs. Ross’s own doorway: KNOW THYSELF IN ORDER TO SERVE. Mrs. Ross has been serving up culture for as long as anyone could remember. Steve Ross was dating Courtney Sale, the art dealer, but chucked her overboard to marry Amanda Burden, from one of the oldest of old-line Wasp families. After Burden left him, Steve came meeching back to Courtney. Epic spending ensued, much of it on art. In Mrs. Ross’s custody is one of the major assemblages in New York of French Art Deco and the best examples of Wiener Werkstätte in the country to be found outside of Ron Lauder’s Neue Galerie. When New York City determined Mrs. Ross owed back income taxes in 1993 and 1994, her collections alone were valued at approximately $68 million.

“I think one of the problems Steve had with his two other wives was that they weren’t the least bit interested in what he was truly good at, which was wheeling and dealing,” says one acquaintance. “But Courtney at heart was a wheeler-dealer, too. She would involve herself in areas someone like Amanda wouldn’t have dreamed of.” Courtney, who by this time was making documentaries about artists, sought the company of painters and intellectuals; Bill de Kooning came for dinner, but some of the others looked down on Steve, considered him a vulgarian.

Her pilgrimage to enlightenment began when Mrs. Ross, in a snit with Spence School, withdrew her daughter, Nicole, and, after a short stint in East Hampton public school, took tutors along on location with Nicole and a few other girls who soon joined them. They spent a little more than a year trekking to Paris, Berlin, London, and the Galápagos Islands, when they weren’t encamped in a studio Courtney had rented in East Hampton. But there were also overnights at her 740 Park digs, where the little girls wandered among her many prize de Kooning Woman drawings, the Lichtenstein, the Gorky, the Pollock, the pre-Columbian textiles, and were herded to museums, Broadway shows, and French restaurants. Mrs. Ross made sure they tried caviar and learned how to set a table with crystal. Her girls called her Courtney. “She was our friend!” says Alex Fischman, who started with Ross in the fifth grade.

When Nicole reached high-school age, boys were introduced into the biosphere. The school by then was undergoing a radical expansion as buildings were being unveiled one by one in the scrub oaks and pitch pines. The Skidmore graduate and self-styled interior designer set about testing her costliest theory yet, as quoted in the school’s brochure, that “beauty in the classroom affects the quality of the lesson.” One could evaluate the project through a Freudian prism, Mrs. Ross re-creating her girlhood, gifting a school—culture!—to a small town on Long Island, and running the entire ranch as its CEO, just like her mother.

“She was incredibly exacting,” says one builder. “You know that fire-breathing machine in Dr. No? I would come out of meetings with her, hold my arms out, and say, ‘Is my flesh still on me?’ ”

“She doesn’t like to hear no. If you said, ‘Courtney, you can’t do that,’ the response would be something like, ‘Oh, really? Let me show you,’ ” says Fred Stelle, the architect who did the master plan for the East Hampton school and was eventually fired, rehired, then fired again.

Says another ex-employee, “It was as if Donald Trump were a school principal.”

Atmospheric conditions permitting, she could work her charms on both sexes. “She kind of looks out of the side of her eye and smiles a sort of lopsided grin and lets her shirt fall open,” says one builder. “But she wanted to get the school finished, and she was very effective.” Wooing prospective architects, she’d offer to whisk them to Kyoto, to learn Japanese joinery! She appreciated an audience and was always scootering VIPs through, soliciting input and sharing ideas with the likes of New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger, Billy Joel, Oprah. When Bill Clinton stayed chez Spielberg, he dropped in to see Mrs. Ross next door on Georgica Pond. World leaders were discussing the Ross mission!

In 2000, Ross completed the spalike Center for Well Being at the school, geothermally heated and cooled, a ski-lodge fireplace on its ground floor, a koi pond in its basement. The local porch-rockers nicknamed it “the Canyon Ranch School.” This was what $1,000 a square foot looked like: Rain Head showerheads (and Ethernet ports) in the locker rooms. Automatic-flush toilets, labeled w.c. in the European manner. Hand-inlaid Mondrian floors in the school’s music room. Transporting the whale-rib-size roof beams required closing the George Washington Bridge to all other traffic.

The children do seem influenced by their surroundings—to the extent that vandalism is rare: Nobody’s drawn a bubble bath in the koi pond yet, and there’s a level of respect not seen at the average cinderblock high school.

In the kitchen, Ann Cooper, now applying her talents to Berkeley, California’s school system, hired restaurant sous-chefs, forged connections with local farms, and showed how any school could almost entirely eliminate all the processed gunk. (She was then asked to help overhaul New York City’s lunch program.) Jay McInerney says his twins, who attend the school, are lecturing him on organic produce, the benefits of better eating clearly filtering upward.

At the school and at home, Mrs. Ross’s staff would ebb and flow, often depending on the state of her personal liquidity—or mood. Mary Rozell was the director of Mrs. Ross’s personal art collection. Her lawsuit against Mrs. Ross is a keyhole glimpse of this politeia’s administration. Rozell claims she was fired after accusing Neil Pirozzi, the CFO of Mrs. Ross’s back-office operations, of sexual harassment. Informed that Pirozzi made provocative comments to her pregnant employee, Mrs. Ross allegedly said, “You never know, Mary, some men get off on that.” Rozell maintains Mrs. Ross cracked sex jokes before wrapping the meeting with, “What do you want me to do about it?” (Ross, through her lawyers, vigorously disputes the allegations in the suit.)

Soon after, Mrs. Ross decided it was time to “restructure” the three-person art department, and Rozell was let go. In the suit, Rozell accuses a Ross employee of improperly hacking into her personal AOL account by supplying AOL with her Social Security number and her mother’s maiden name, allegedly allowing Mrs. Ross to read her e-mails. One of Ross’s executives maintains that the account was not a personal one but was paid for by Ross. Ross teachers often suspected their e-mail was being read. Asked in a deposition if she authorized employees to access e-mail accounts, Ross responded, “Not unless it had to do with the school … The school owns the e-mail.”

“If you weren’t loyal, you were gone,” says a former teacher there. “She was the Goddess. You had to obey, and if you disagreed, you were sent away.” Teachers who started out in the fall sometimes didn’t last through the spring. Students called this Mrs. Ross’s “spring cleaning.”

In the early days, Mrs. Ross would request meetings in the middle of the night, and call Nicole’s teachers on the phone during class, says former head administrator Marc Anthony Meyer. “I am a 24/7 person, and most people who work for me are 24/7 people,” Mrs. Ross explained in a deposition in the Rozell suit. Her duplex office, where she presided over meetings at Steve Ross’s old conference table, was completely finished when she changed her plans; everything was torn out and thrown in a Dumpster, says another ex-teacher. “That school ripped souls out of people,” says one former employee. “She’s a very difficult woman to be around.” (Still, Meyer calls her a visionary, crediting her with changing his ideas about education.)

In the city, Mrs. Ross appeared no less mercurial, flipping out when she discovered her art staff didn’t have an exact count of all her china, the Rozell action claims.

The curriculum on display at her new charter school has several parents. In 1991, Mrs. Ross went straight to the top of the pyramid—Harvard—hoping she might induce its legendary edu-school hierophant, Howard Gardner, to involve himself in her drawing-board project.

Gardner does not dispute the use of the word visionary in relation to Mrs. Ross. “People in Hollywood and people who are in these large multinational corporations think very big,” says Gardner. “Scholars are more afraid of making mistakes. We let our visions be clipped. She’s much bolder than that.” Gardner’s celebrated theory of multiple intelligences—if a child struggling with reading is really musical, there is surely a way to improve his reading by using music—has left its thumbprint on the school.

According to one of her closest curriculum advisers, Mrs. Ross’s quest to find a slick new curriculum for her school gained momentum when she saw the New Age magazine Yoga Journal sitting on the desk of a Hollywood friend. Inside was a piece about Ralph Abraham, one of Santa Cruz’s voguish chaos-theory collective, a Berkeley-affiliated mathematician who for several years lived in a cave in India and slept on the streets of Europe, nourishing his cortex with psychedelics. She got in touch with Abraham, who turned her on to William Irwin Thompson, the founder of the Lindisfarne Association, a kind of gorp-fueled think tank. Thompson was living in a log cabin on a remote Zen monastery in Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and Abraham and Ross set out on a G4 to try to persuade him to climb aboard.

Thompson had homeschooled his own son, but the former MIT professor had little experience with primary and secondary education. Ross captivated Thompson. “She’s not an intellectual, and she doesn’t pretend to be,” he says. “She’s modest and straightforward about that, but she’s very intelligent and imaginative and entrepreneurial. She’s so busy she can’t sit still and read a book from beginning to end, but that’s true of a lot of politicians.” Mrs. Ross sometimes has employees read aloud to her, and has paid for summaries of books.

It was Thompson who introduced Mrs. Ross to the ravishing concept of the Goddess, a controversial theory that enjoyed a moment of cosmic voguishness in the late eighties after primarily female fertility idols turned up at archaeological digs and some postulated that, early on, women had shaped a pacific course of history, only to be subverted by men. Even after boys arrived at the Ross School in 1998, students continued to be taught that women were the creators of culture—the progenitors of ceramics, botany, agriculture, medicine, astronomy—until a runaway system of conquest and perpetual warfare initiated by men displaced women from traditional authority and power. “I wanted to make sure the girls were empowered with the sense of culture, and everything wasn’t biased toward a military narrative,” says Thompson.

Ultimately, Thompson’s vision was out of sync with Gardner’s. Thompson believes Gardner stirred the pot with Mrs. Ross, telling her that “Bill Thompson is New Age,” and that if the school was identified as such, she’d lose Harvard’s respect. Gardner did find the curriculum New Agey. “But what I really thought was foolish was all that stuff about how everything came from matriarchies,” Gardner says. “How can we possibly know this?” He pleasantly allows that Thompson’s curriculum is impressive: “It’s important to have a backbone, even if it’s not one scholars are going to approve of.”

The faculty was skeptical that Bill Thompson’s curriculum would work. Following a strict chronological approach, one wouldn’t hear a whisper about America until the tenth grade—since America didn’t yet exist. The challenge was to find ways to discuss things that the chronology left out. Discussing slavery in Egypt, a teacher could draw parallels with slavery in the Deep South. Math and science were always problematic, since the major breakthroughs occurred in fits and spurts not neatly coinciding with key moments. Students wound up having deficiencies in math, which the school has been trying to rectify, with some success, thanks in part to Ross’s SAT classes. Mrs. Ross had always had her admissions department “choreograph the class,” as she phrases it, with purposeful recruitment of minorities and other students whose passions and potential might never be revealed by test scores.

At age sixteen, the school has been forced to grow up. Some of its proggy ideals have been flung on the pyre as Ross comes under pressure to teach to the test. The cultural-history classes used to go on for three hours at a stretch. Tai Chi every morning in the big gym with the entire school was discontinued so classes could start earlier. “My personal feeling is that Ross is under the thumb of the system,” says Roy Scheider, whose son Christian is a Ross junior. “They are fashioning themselves into a college-prep academy and not necessarily preparing children for life.”

Bill Thompson is no longer affiliated with the school: “The role of an architect is not to hang around the building and tell people how to live in it,” he says regretfully.

People who’d worked for Mrs. Ross claim she invested money in the search for Atlantis, but she is more than a dilettantish dunderhead with a vanity institute. Still, she does like her summits and symposia. She met her second husband, Anders Holst, at a ted conference in 1997, five years after Steve Ross died. A Swedish management consultant with soap-opera looks, he was nearly a decade younger and had been married with kids (“what Jung would call a puer eternis” is how Thompson pegs him). A year later, he’d moved to the States, and she was talking about doing a school in Stockholm.

Mrs. Ross appointed him her unpaid co-chair of the Ross Institute, and he worked hard to find a role for himself. They were wed in June 2000 in Florence’s Orsanmichele, which reportedly received $1 million for its restoration. A special libation was prepared, a blend of Armagnac vintages from the years she and Holst were born. Ten members of the First Baptist Church of Bridgehampton choir were on hand to sing a single song: “I Believe I Can Fly.” Holst compared the event to being awarded the Nobel Prize. But now, inspired by hanging out with Billy Joel and Mrs. Ross’s friend Quincy Jones, Anders Holst repackaged himself as the Sting of smooth jazz. Mrs. Ross prepared a studio for him and hired him the best sax backup guys in the business, but she viewed his music as a hobby, and he was spending an awful lot of time in Sweden, working on his songs. They divorced in 2005, after which Holst bought himself a $3.2 million penthouse loft on lower Broadway.

As her marriage was unraveling, Ross was plotting her advance on New York City. Finally, last spring, her people were ready to hit the Pentecostal iglesias and community centers of the Lower East Side to spread the word about her new charter school.

Mrs. Ross was restless: Chancellor Klein had promised her space at the nest+m school, the warm, welcoming acronym for New Explorations Into Science, Technology, and Math. The Nesters claimed that the reduction of classrooms in their designated gifted-and-talented school would increase their class sizes. They expressed concern over how the Ross Global kids who would share the building might “comport themselves.” It was easy to call the Nesters racist, as more than 50 percent of the students are white. But a trait of new charter schools nobody likes to discuss is the idea that the upper grades are sometimes stocked with kids who have bombed out of other schools or have just been “passed through the system.”

The Nesters liked to insinuate that Mrs. Ross and Joel Klein are personal friends, members of the same Hamptons clubs, and that Mrs. Ross has served on some boards with Klein’s hyperconnected wife, Sony’s general counsel Nicole Seligman. (“All untrue,” says a Klein spokesman.) Still, people talk about Klein’s ambitions to be mayor, and charter schools as a cause puts him in contact with the city’s deepest pockets.

In the midst of the protests last year, Mrs. Ross toured the school, expressing her preference for the classrooms on the east side. The Nesters maintained these were best ones, the best lit, overlooking the trees (all three of them). Mrs. Ross’s architect was measuring rooms with some ray-gun thingie, “and one of her little photo slaves was taking millions of pictures,” says Emily Armstrong, the PTA’s then-president.

This being New York City, the PTA took the Department of Education to court. When it came time for Mrs. Ross’s lottery, she arrived at what is locally known as the Chinatown YMCA—to an ambush. Children were screaming, parents were cursing and throwing water. toss ross posters thrust in the air depicted Mrs. Ross done up as Cruella De Vil or wearing a little Hitler scribble-mustache. (The Nesters called her an anti-Semite when she expressed her wish to conduct school on Saturdays, a common charter practice.) Klein has since cracked a few heads at nest+m, replacing the principal. After the Department of Education sent investigators to audit the PTA, its ringleaders resigned.

Reached by phone in the PTA’s office, Emily Armstrong was photocopying whatever she could get her hands on. “They’re treating us like Enron,” she said. Sitting just outside were men from the city’s Office of Investigations, wearing black trench coats. “Like the Gestapo!” screeched the PTA’s now-former executive vice-president Lou Gasco.

By June, Klein caved, and offered Mrs. Ross space in his building, the Tweed Courthouse. But Tweed had its own problems. Mrs. Ross had only about three weeks to get the space ready for the first day of school after the prior tenant, City Hall Academy, evacuated, but then the construction workers were pulled to work on the 9/11 memorial. On the eve of the school’s opening, she was there helping to deliver things, assemble bookcases, unpack books, put chairs together at midnight. As awe-inspiring as the space is, it is not designed to be a school. DOE employees have license to traipse through the space, and the children are obliged to pass through metal detectors.

Mrs. Ross’s architects were summoned: They grappled with how to carve every room in two with soundproofed walls that couldn’t touch the ceilings so as not to deny any teacher light from the sash windows. But for the most part, the revamp has been poorly reviewed by its tenants: An L-shaped classroom is fine in a private school but not in a public school, where teachers are compelled to see every kid at all times. The inner sanctums with doughnut-shaped tables where the children could wander off and read—that was the theory, anyway—can’t be used unless the teacher is literally standing in there, too. There are too many “perversion pockets,” as these areas are known in the public-school-building field. Insiders deemed it a battle of aesthetics versus pedagogy.

“We’re in survival mode here,” says one employee, adding, “Frankly, I’d rather be in Africa with a dirt floor.”

Mrs. Ross brusquely told the staff to stop whining. By September, the thunderbolts were flying. Ross Global’s first principal, public-school veteran Jon Drescher, who was telling people that Mrs. Ross needed to let the mechanism of the school work and stop making all the decisions—“This is my fucking school,” she was known to scream—was diagnosed with the stress-related illness shingles. Drescher departed a couple of weeks before school started, informed that, among other things, Mrs. Ross was irritated by his insistence on going to visit his Westchester doctor during teacher orientation in East Hampton.

Mrs. Ross at times seemed to be spitting nails at Terry Cook, her chief of staff of a single month. And after the school moved into the Tweed Courthouse, the school’s avuncular black president, Dr. Mark English, a man who’d taught at West Point and the National War College—the former commandant of West Point Prep, whose responsibilities included hiring faculty—was informed that his presence wasn’t wanted in the building. He was now to conduct all business from Mrs. Ross’s Soho offices.

Mrs. Ross was always deciding she knew best, suggesting they start up a summer school before the location was even finalized. And for a time, she decreed that the fifth- and sixth-grade teachers instead of the students be the ones to pack up all their things and move from room to room at the end of each period. English lost the fight over the uniforms Mrs. Ross was demanding—including shoes and extra shirts that could cost students as much as $200 (25 percent–off gift certificates were eventually distributed). English disappeared the first week of November; not long before, he’d arranged for a photo to be taken of Chancellor Klein with the children when Mrs. Ross was out of the country, and some wondered if the two events were connected. (“If you don’t get the right person, you make the change,” board member Marty Payson explains.) In its first few months, Ross Global lost art, music, and Chinese teachers, a kindergarten teacher, and two sixth-grade instructors. A Ross spokesman maintains that the turnover has only strengthened the school’s programs.

In December, ready to call a public board meeting to order, Mrs. Ross slipped a priestessy, serapelike vestment over her shoulders and introduced Frank Marchese, a brand-new principal who’d started an impressive charter school once upon a time in Ontario. He seemed jittery. Later, after about two weeks full-time on the premises, he would find himself replaced by the woman on his right, Dr. Stephanie Clagnaz, now being introduced as the new assistant principal. “I feel totally secure,” said Clagnaz last week. “Members of the board have given me free rein and autonomy.”

What was transpiring below stairs at the chancellor’s office seemed only to validate teachers-union president and Klein critic Randi Weingarten’s most painterly nightmares about charter schools. Mrs. Ross had always insisted that the after-school and Saturday programs be free of charge. Money was somehow found to conduct them anyway. Mrs. Ross has already picked up the tab on a number of extras, including the decorating job, says Payson.

In August, before the doors opened, Mrs. Ross learned that 18 to 20 percent of the students were identified as having some sort of special need, an extraordinarily high figure. Mrs. Ross rose to the challenge, insisting on taking every child no matter the disability. Ross Global is having a time of it providing these services, and of course that affects what happens in the classroom. Some children have been disruptive and prone to violence.

A lot of baby schools wouldn’t have gone down this road. NYU’s Steinhardt School of Education dean and Ross Global board member Mary Brabeck cites the phone calls she gets from Mrs. Ross at night, the e-mails. “This is really hard work, and it’s so bloody punishing for people whose job it is to do it,” says Brabeck, applauding Mrs. Ross’s resolve. “But I think she gets great joy from seeing ideas come to reality in ways that make the life chances of kids better.” The Goddess has revealed herself here too, in the fifth grade’s study of the epic poem “Gilgamesh,” dramatizing the rise of the heroic male challenging the goddess of life to escape death, and in sixth-grade readings on the clash between a culture favored by Aphrodite, the ancient Near Eastern goddess of love, and a warrior society championed by the helmeted Athena, the new daughter of the patriarchy—otherwise known as the Trojan War.

“One thing that’s unwavering is Courtney’s commitment,” said Ross Global parent Elias Rodriguez. “Ultimately, this endeavor—from my perspective—is about helping two Puerto Rican kids from the Lower East Side.

“I usually don’t take lunch at twelve, but every once in a while I do,” continued Rodriguez, who works nearby at the Environmental Protection Agency. “There was one day in the fall—I was on the other side of the gate—and sure enough, both kindergarten classes were running around having fun. Courtney was out in the yard, just mingling with the kindergartners, out in the yard.”

“Jesus says, you tell a tree by the fruit it bears” is what the Reverend Jesse Jackson is reminded of when he thinks of Mrs. Ross. There she was, out in some yard behind a cafeteria, engulfed by a shrieking, giggling swarm of kindergartners. A Ross-school educator would call this one of Piaget’s meaningful contextual situations. Mrs. Ross didn’t have to be here: She could have been floating around on a yacht somewhere.