D avid Wright is not a very good bowler. He would like you to know this, should you think that being a very good baseball player, which he is, would somehow translate to being a good bowler, which it does not. He admits to bowling frequently, bowling being one of the few leisure activities available in Port St. Lucie, Florida, home of Tradition Field, the Mets’ spring-training facility. He also has his own bowling ball and shoes, which, he knows, may look a little suspicious, like signs of a highly competitive personality, which is something many people (Wright included) talk about when they talk about Wright. But no, no—it’s not that. “It’s for hygiene purposes more than anything,” Wright says while tying his shoes at Superplay USA, a massive complex that contains a beer pub, an arcade, a laser-tag arena, a mini-golf course, batting cages, half the population of Port St. Lucie, and a 48-lane bowling alley. “I’m not like a hygiene freak or anything. I’m just not so into wearing other people’s shoes and sticking my fingers in things that strangers have touched.”

A bowling alley is a particularly fitting environment in which to spend time with Wright. At 24, he comes across as so wholesome that you suspect he was cryogenically frozen sometime around 1955 and thawed out three years ago, when he made his first start at third base in the major leagues. His friends note, almost apologetically, that he is unwaveringly polite and humble, and even those who hate him admit that … actually, scratch that. No one hates David Wright. In fact, when people talk about him, they tend to fall back on a certain refrain: “I’m sorry, but you’ve just got to love the kid.” To support this claim, they will point you in the direction of Wright’s smile, which seems to have transformative powers. Professional athletes these days, baseball players especially, are not expected to smile. They are expected to bemoan their contracts and question their teammates’ skills and act prickly with fans and lie about not using steroids. But when Wright hits a home run, or even when he doesn’t, and especially when he gets ragged on in the clubhouse for being such a pretty boy, his reaction is uniform: the pinched dimples, the flash of white teeth, the brown eyes sparkling—a random combination of muscle movements offering infinite branding possibilities.

Tonight, Wright is joined by John Maine, the Mets’ wiry 25-year-old pitcher, and Joe Hietpas, a 27-year-old minor-league catcher with a lumberjack’s build. On the team, Wright is closest with the younger guys, those who share his non-baseball interests (PlayStation, hip-hop) but have little in common with him when it comes to their careers. Midway through last season—which ended with the Mets one heartbreaking game away from the World Series and almost eclipsing the Yankees as the New York team—Wright signed a contract for $55 million over six years. It was a lucrative and symbolic declaration on the part of franchise executives: Wright is not merely a player with the talent to anchor a team, he is a star in the old-school mold, a galvanizer, pure packaged Americana. “There have been other kids in our organization who you latch onto and like, but then, for whatever reason, they don’t make it,” says Mets COO Jeff Wilpon. “David is the exception. I’ve been lucky enough to meet guys like Michael Jordan and Wayne Gretzky, and I believe David has that thing, you know, that same approach to the game that made them so addicting to watch.”

Everyone is settled in, prepared to bowl. Maine reaches into his back pocket for a tin of Copenhagen chewing tobacco. Hietpas orders a pitcher of Bud Light. “No thanks, I’m good,” says Wright, who is not a teetotaler but often talks about drugs and alcohol as if he were auditioning for a dare commercial. (“When you’re coming up, they have meetings with you about drugs, about drinking, about women. They hire these actors who come in and perform a bunch of scenarios. It’s pretty funny and basic, but it sticks in the head of someone who’s 18 or 19 years old.”) As the game starts, there is a subtle shift in Wright: He bounces on his toes, as he does when he’s playing third. He chides Hietpas—“The objective is to knock over the pins!”—but he goes easier on Maine, who’s bowling left-handed to protect his throwing arm. Finally, when it’s Wright’s turn, a smile comes over his face—the smile—as if he already knows what’s going to happen next. “That’s what I’m talking about,” he yells upon releasing the ball. Every pin topples in a perfect strike.

It is a strange and unpredictable thing, the combination of forces required to turn a gifted athlete into a celebrity. Historically speaking, those who have made the transition in New York have been blessed with an intangible quality that links them, intrinsically, with the era in which they play. In the fifties, there was Mickey Mantle’s all-American grit. Then came Joe Namath in the sixties, the shaggy-haired playboy in a mink coat. Reggie Jackson’s style of play was perfectly in line with the city’s unhinged ethos of the seventies: He either struck out or hit a home run, always with a dangerous swagger. The eighties produced its share of rabid personalities—Lawrence Taylor, Mike Tyson—who, like the stock market, were destined to crash. Derek Jeter, of course, was and remains pure nineties—slick, telegenic, a winner—and it appeared that Alex Rodriguez was destined to inherit his mantle when he joined the Yankees three years ago. Handsome, bilingual, arguably the best player in baseball, Rodriguez—on paper at least—seemed created in a lab to please New Yorkers. But in person, alas, he is A-Rod: sulky and insincere and humorless, an incredible player who is almost impossible to root for.

David Wright benefits from a persona that perfectly dovetails with Bloombergian New York City. He is unthreatening, tourist- friendly, a bit corporate, but charming nonetheless. A modern-day throwback, he satisfies a retro craving for a time when growth hormones were injected only into livestock. (On the subject of Guillermo Mota, the Mets pitcher who tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs last year: “We were hoping he would be a major factor, and now he’s out 50 games. What good comes out of that?”) Given that some of the Mets’ brightest hopes peaked early (Darryl Strawberry, Dwight Gooden) or were overhyped (Alex Ochoa, Kaz Matsui) or suddenly forgot how to play upon joining the team (Roberto Alomar, Bobby Bonilla), Wright’s ascension has been especially restorative.

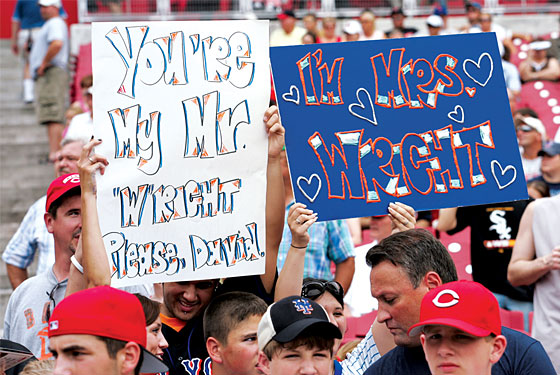

Wright’s greatest strength is that he’s an all-around player: a solid fielder, a fast runner, and an abnormally patient batter for someone so young. He is not, however, the most gifted athlete on the Mets—that would be Jose Reyes, the silky, Dominican-born 23-year-old shortstop. Wright and Reyes are often talked about in tandem, the young infielders who will lead the Mets into a new era. But much of the fervor has focused on Wright, for some obvious if unsavory demographic reasons. He receives hundreds of marriage proposals a year, and during any given home game, he can gaze into the stands at Shea Stadium and see countless young (and not so young) women wearing shirts reading mrs. wright. His hitting pose—arms flexed, stocky frame in a post-swing coil, tongue flapping—is currently featured on the cover of the popular PlayStation game MLB 07: The Show, and the think tank that advises Madame Tussauds about which celebrities to cast in wax—yes, such a thing exists—chose Wright to be the first Met to have that honor. In February, perhaps feeling the fever, or hoping to improve his image, President Bush invited Wright to dinner at the White House. (“Oh, man, it was incredible,” says Wright. “He didn’t take a single call the entire time.”) His endorsement deals include Vitamin Water, Wilson, and Delta Air Lines, which christened a plane “The Wright Flight.” And in the wake of a hot streak last June—winning the National League’s Player of the Month award, going to the All-Star Game, placing an unexpected second in the Home Run Derby—he appeared on the Late Show With David Letterman, the effect of which is best described in the following posting from the Wrightoholics blog:

Hello Everyone, Just a short blog entry before i go sleep on my David Wright comforter and On my David Wright pillow. David truly did inspire us all tonight on the Letterman show … He will be the new Derek Jeter of Ny and everyone knows what Derek did for the Yankees … We all know we dont want David anywhere else and if that does happen, I will … grow a long beard and live in the country style for the next 40 years and think what could have been, So mets dont do it.

You would think that there would be more-ideal places to witness this zealotry than Port St. Lucie, a moonscape of strip malls and chain restaurants and palm trees that couldn’t be more psychically removed from New York. Exhibition games at Tradition Field are typically low-octane affairs attended by a few sunburned retirees and their distracted grandchildren, but during a recent matchup against the Cleveland Indians, the stands were full and raucous and peppered with fans wearing Wright’s jersey—No. 5—which last year outsold Jeter’s in the tri-state area, something that no one had done in eight years. Among them was Daren DeLuca, a barrel-chested 40-year-old from New Jersey, and his brother-in-law, Isaac Gomez. “Had a few days off and just figured I’d come down, check in on my boy,” DeLuca said. As they stared at Wright, bouncing on his toes over at third, a peculiar look washed over them, one unique to baseball and not seen on the faces of Mets fans in some time: Here were two men feeling intensely nostalgic for the present.

“I’ve been a fan of this team since the seventies,” said DeLuca, riding out his moment of Zen. “And how many third basemen have we had? We’ve had like a million. They come, they go, they don’t work out.” He took a salutary swig of lukewarm beer. Gomez nodded. “But not this kid, no. He’s gonna be a legend, you can just feel it. He’s clean. He’s the quintessential pro.” As DeLuca spoke, the Cleveland batter cut into the ball—thwock!—hitting a fierce grounder that took an odd hop, vectoring toward Wright’s face. DeLuca and Gomez rose to their tiptoes. The ball was bobbled, seemingly an error, but, hold on, Wright adjusted and made a hard throw to first, beating the runner by a few inches. “Ohhhwaaa!” DeLuca shouted. “See that? Not the play. But see that smile? That’s what I’m talking about! That charisma! I’m telling you, man, he’s our Jeter.”

“Our wives love him,” added Gomez, for emphasis.

“Our wives want to marry him!”

“They really do!”

“Hell, I want to marry the kid,” said DeLuca, clinking bottles with Gomez. “I said to my wife—I said, ‘Honey, if I don’t come back, it means I ran away with David Wright.’ He’s helped bring the fun back to this team, okay? Which, believe you me, was missing for a long, long time.”

In 2004, when he was brought up from the minors in the middle of the season, Wright rented an apartment on the Upper East Side: a fine modern spread with astonishing views, which he tended to leave vacant during the off-season—preferring, like a college kid, to move back home to Chesapeake, Virginia, with his parents and three younger brothers. Most professional athletes are full-time nomads who spend half the year in buses and hotels and rarely live in the city for which they play. But to be a star in New York, you have to be more than a commuter, a fact that Wright understands. In December, he bought a $6 million loft in the Flatiron district, which he’s currently renovating, checking in constantly from Port St. Lucie to make sure everything will be ready by April 9, the day of his first home game. “Since I have literally just about no taste and no understanding of what colors go with what, I hired an interior decorator,” Wright says one day over lunch, his tone somewhat embarrassed. “Basically, I told her I wanted it to be the ultimate bachelor pad. We’ve butted heads a few times—she wants more color, I’m into the grays and blacks—but it’s been a pretty smooth experience.” When asked a question almost mandatory for wealthy, modern athletes—how many flat-screens do you have?—Wright uses both hands to count. “A lot,” he says, unable to remember exactly. “I was at the ESPN Zone—you know it? In Times Square? Anyway, I based my media room on how they do their TVs. I’ve got five in there so I can watch every football game.”

Wright says he was always a “displaced New Yorker,” though it is because of his relationship to the city’s sports teams more than to the city itself. As a kid, he was a Giants fan for reasons that offer a glimpse into his competitive nature. “My father was a Redskins fan, so I picked one of their biggest rivals,” explains Wright with a laugh. “I basically looked for any excuse to compete against him. That’s just how I am. Always been that way. Can’t explain it.” As has been noted by many a sentimental sportswriter, he also grew up cheering for the Norfolk Tides, the minor-league team that, at the time, served as a farm club for the Mets. When Wright talks about New York, he has an endearing tendency to sound like a man trying to memorize a tourist brochure: “Just living here, I feel like I’ve become more cultured. The museums, the people. In Virginia, where I grew up, it was a very conservative town. Just take the food in New York. I don’t know if I’d ever had sushi before I came here, but in New York, every other place is a sushi restaurant.” So the city has changed his worldview? “Oh, yeah, definitely. I drive a lot faster and more aggressively whenever I’m back home. And people will sometimes call me out for slipping in the New York accent. And talking too fast. People back home say I talk too fast now.”

Many have noted that Wright, despite his age, is preternaturally savvy with the media. Indeed, in person he is accommodating but distant, a touch mechanized, someone who never strays from the lessons of those “How to Behave” sessions years ago. His locked-down quality comes, perhaps, from being the son of a cop: He learned early on to stay in line, do things right, lead by example, keep himself in check. “I’m really careful about making friends, about who I surround myself with,” he says. “Most of my friends are people I’ve known since I was a kid. I don’t have an entourage or anything—I like the show, but I think they’re kind of absurd. I just make sure I’m around people I can trust.” Remarkably, given that he’s come up in a tabloid era, he seems to have immunized himself to scandal: Search far and wide on the Internet, and you’ll find a few snapshots of him doing shots with some friends (reportedly St. John’s students), but nothing more. This requires vigilance. Any misstep, no matter how small or well intentioned, has the potential to backfire. A minor stir was recently manufactured, for instance, when Wright told reporters, half-seriously, that he’d switch to any position if A-Rod were to leave the Yankees and come to the Mets. Last year, he unwittingly spawned a low-grade controversy when he was approached by someone on the field asking him to film a promotional spot for the “Salvation Miracles Revival Crusade.” Though dubious-sounding, he assumed it was franchise-sanctioned and obliged. “Hi, I’m David Wright,” he says perkily in the spot. “I invite you to the ‘Salvation Miracles Revival Crusade’ with Dr. Jaerock Lee at Madison Square Garden…,” at which point the screen cuts to an image of a man holding up his crutches, having been healed by Dr. Lee. “That was really my fault,” says Jay Horwitz, the Mets’ director of public relations. “There’s so many people on the field, and David’s so accommodating. Most guys won’t even bother, but he doesn’t like saying no to anyone.”

In the clubhouse, Wright is both rabble-rouser—towel-snapping the guys who still seem half asleep—and diplomat—speaking pidgin Spanish with the Dominican contingent. Being someone often referred to as one of “New York’s most eligible bachelors” makes him an irresistible target for friendly mockery, which he takes in stride, sometimes preemptively striking first. With Tom Glavine, the team’s patriarchal 41-year-old pitcher, Wright jokes, “Hey, man, I was a huge fan of yours when I was in elementary school.” To which Glavine has a stock rebuttal: “Look, you’ll be lucky if you’re still playing at my age, and you won’t look as good as I do.” Paul Lo Duca, the starting catcher and wiseacre-in-chief, has made it a priority to keep Wright in check. “He thinks every woman in the world is in love with him, so we give him some shit, keep his feet on the earth,” Lo Duca says. “I tell him that if he was a garbageman, not a single woman would notice him. Glavine always says, ‘When I was your age, every woman loved me too. It’s not you, it’s the uniform on your back.’ ” Wright, for his part, has a well-rehearsed comeback. A woman flirts with him, the guys give him hell, and he says to the guys, “Hey, she can’t help it. She’s only human.”

The good looks, the money, the ultimate bachelor pad: Comparisons with Jeter have become inevitable. Like Jeter, Wright entered the major leagues at 21 and is a pure product of his team: drafted and groomed when he was still a teenager. Growing up, Wright idolized Cal Ripken Jr., but Jeter has become his model for playing in New York. “He’s offered me some great advice,” says Wright. “He just says to remember who you were when you started playing and don’t change. It sounds simple, but it’s not. You wear the uniform, you’re under a microscope. He has his social life, but he’s also someone kids look up to. That’s a hard balance. I’m very conscious of what it means to wear the jersey, but at the same time, I’m a 24-year-old who likes to do what any normal 24-year-old does.” But Jeter, of course, is known for having dated a variety of high-profile women—Mariah Carey, Jessica Alba—whereas Wright can sound vaguely monastic on the subject of dating. “I don’t want to put them in the same category as drugs, but women can be a … a distraction,” he says. “I have to remember, baseball is the reason I have my apartment, baseball is the reason I’m on the cover of video games—baseball is what I do. I’m not saying I don’t ever … I mean, I go on dates, but I’ll just never let something like that become as important as the game. Not right now, at least.”

All baseball, all the time. Such unrelenting single-mindedness can come across as extreme—robotic, even—but Wright knows he has a critical year ahead. Having won their division for the first time in eighteen years last season, the Mets are no longer a team of just potential. This season, the expectations will be raised: Fans are less likely to be enamored of Wright the Phenomenon if it distracts Wright the Player, as some suspected it did when he fell into a minor slump during the second half of last year. “People say there’s a lot of pressure here, but that’s what I live for,” says Wright. “No one puts more pressure on me than I do.” Recognizing his evolving role on the team, he knows he has to graduate from boy wonder to bankable commodity, never mind his age. “It’s important to be a leader, especially to the younger guys,” he says, a statement that gives him pause. “It feels weird to say that—I mean, just a couple of years ago, I was one of them. I guess, in a way, I still am.”

A t Superplay USA, Wright has been spotted. A middle-aged woman asks if he wouldn’t mind signing … a framed poster that she apparently has been carrying around, hoping for such a run-in. A teenage girl asks him to autograph a takeout menu, another her boyfriend’s hat. “He’s too shy to come over,” she says, “but he was like, ‘I’ll kill you if you don’t get him to sign this.’” A clique of students from James Madison University take the lane next to Wright’s, and ask for a few cell-phone portraits. Because Wright is both so young and so polite—he takes ten minutes after every practice to sign autographs—people are more comfortable than awestruck around him. “Hey!” says a waitress, handing him a napkin. “Will you sign this even though I’m a Cardinals fan?” (The Cardinals won last year’s World Series after edging the Mets out of the playoffs.) For a moment, Wright pretends to be offended—brow furrowed, a shake of his gelled head—before scrawling: To my favorite Cardinals fan, the Mets rule!!! David Wright.

Between these sessions with his fans, Wright continues to bowl. Strike after strike after strike. He easily wins the first game, calling into question his earlier proclamation about being a mediocre player. “Yeah, this is pretty much how it goes,” says Hietpas of the drubbing. After a second loss, Maine and Hietpas lose interest and drift over to the arcade, where they start feeding bills into a free-throw basketball machine. Wright keeps an eye on his watch, making sure it doesn’t get too late. The team is playing the Red Sox tomorrow, and the guys have to be up at 5:30 a.m. At ten, Wright decides it’s time to call it a night. “Let me go round up these idiots,” he says, making his way toward the arcade’s blinking lights, where he soon becomes distracted by the prospect of a new competition. “Let me get one shot in,” he says, a grin coming over his face. “Actually, I think we’ve got time for a quick game.”