The inside of Wesley Autrey’s brand-new four-door Chrysler Sebring smells of aftershave, and the CD player is blasting The Best of the Gap Band. We’re squinting straight into a blinding rush-hour sunset, hurtling west on the Cross-Bronx Expressway, out over the George Washington Bridge, on our way to see Jason Kidd and the Nets get clobbered by Allen Iverson and the Nuggets. Wesley is behind the wheel; in the back is his 15-year-old nephew Elias, a basketball fan whom everyone calls La-la and who is glad tonight to be in on his uncle’s good fortune (if not his uncle’s eighties sound explosion). The car is a gift to Wesley from Chrysler, a loaner until he gets the 2007 Jeep Patriot he was promised in January on the stage of The Ellen DeGeneres Show. The tickets are a gift, too, from the Nets—season tickets for two years. When you’re the Subway Superman, some people just like giving you things.

Later tonight, we’ll talk about the downside of instant fame. But right now, Wesley is talking about the good things. Like Beyoncé. When he was on Ellen, the diva appeared to him in a vision—via satellite, actually—promising backstage passes to an upcoming show. Just thinking about Beyoncé, with the soundtrack to his younger years pumping on the Chrysler’s speakers, makes Wesley break into a sweet, wistful smile.

“I’m gonna meet Beyoncé?” he asks. “I can’t wait. I always tell my nieces and nephews I’d like to have a woman like Beyoncé.”

I laugh. But Wesley is serious. He’s making a point.

“She would be the ideal woman,” he says. “She’s got a good head on her shoulders, her own business. She’s someone I wouldn’t mind signing a prenuptial agreement with, know what I’m saying? What possibly could I do for her financially that she don’t already have?”

As we cross into New Jersey, Wesley talks about the emotions he’s cycled through in the past few months—euphoria, confusion, anger, disillusionment, hurt. It’s not that Wesley regrets throwing himself in front of a speeding No. 1 train to save the life of a stranger. He’d do it again in an instant, even if no one heard a word about it. And it’s not that he doesn’t appreciate the good things that have come from what he did. It’s just that the whole experience has proved to be a lot more complicated than he expected. “I thought I’d have fifteen minutes of fame and that’s it,” he says. “Hollywood? The political arena? Movie deal? Book deal? I’m just letting the good Lord guide me. I’ve never dealt with this.”

Wesley veers off the turnpike at Exit 16, the entrance to Continental Airlines Arena. The last time he was here, he tells me, he sat with the team’s owner. He rolls down the window.

“Wesley Autrey, subway hero,” he tells the attendant, flashing his tickets. “Where can I park at, so I don’t have to walk far?”

The attendant waves him through— “Up the hill to the left.” Wesley taps the gas pedal and laughs. “That’s the greatest thing about all of this. They recognize me!”

The arena’s lots are a maze. With every turn comes another gatekeeper. The next one waves him through. He’s two for two. “I love it!” he says.

There’s another attendant. “Yeah,” says Wesley. “Where can the hero park at?”

This one takes his time. He examines the tickets, then checks with a co-worker with dark sunglasses. The man looks at the tickets and slowly shakes his head. “K-20,” he says. Siberia.

For a rare moment, Wesley is silent.

Then La-la starts ribbing him. “Oh, my God! We are so far away!” he says with a teenage groan.

And Wesley just laughs his loudest laugh of the night and starts singing along again to the Gap Band: “I said oops-up-side-your-head, I said oops-up-side-your-head!”

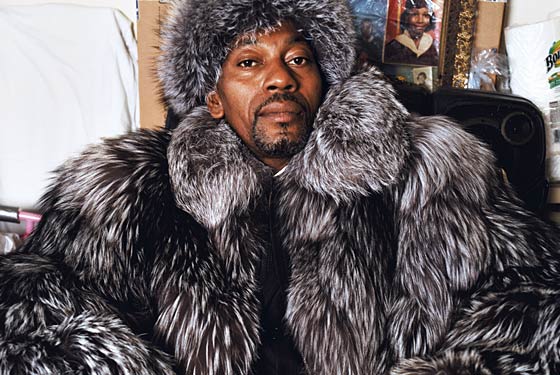

Being the Subway Superman, it turns out, is a lot harder than it looks. Yes, since saving 20-year-old Cameron Hollopeter after he collapsed and fell onto the rails at the 137th Street subway station on January 2, Wesley Autrey has been showered with adulation and no small amount of material goods. Donald Trump wrote him a check for $10,000. He was jetted for free to the Super Bowl. He’s received cars and vacations, fur coats and expensive meals. He’s been honored by Mike Bloomberg, Eliot Spitzer, and Hillary Clinton, and was singled out by George Bush at the 2007 State of the Union address (that’s when Wesley blew kisses to the nation that morphed into peace signs—the gesture became his trademark, and something everyone in Harlem, where he lives, mimics back to him now). He captivated the famously unsentimental David Letterman, and brought his little girls on Ellen. B.B. King literally dropped to his knees and thanked him for what he did. One woman on the street told him she was glad she didn’t abort her unborn child because the Subway Superman showed her that the world isn’t so cruel after all.

Those are the happy aftereffects of overnight megastardom. Then there are the crushing demands on his time, the friends and family looking for handouts, the money problems, the identity questions, and the lawsuit.

On a sunny Tuesday afternoon in March, Wesley Autrey is sitting on the couch with his sister Linda at his niece Quiana’s two-room apartment in the Bronx. Since reporters started staking out his tiny studio on Riverside Drive in Harlem, Wesley has used Quiana’s home as a sanctuary—somewhere to escape to without having to leave town. Wesley and Linda have always been close, but the last few months have made them closer; he’s come to rely on her and Quiana to handle his scheduling and a large part of his business affairs. “I don’t know what I’d do without Linda,” he says. “I’ve got to go somewhere and find an award for her.”

Before he came to the attention of half the Western world, Wesley was known to his friends and family as a modest, hardworking construction worker and something of the family patriarch. He was born in Pensacola, Florida, in 1956 and brought up on a farm in Alabama with an older brother and two younger sisters until he was 12, when the family moved north to Harlem. The second-oldest of four kids, he’s never not been the man of the house. His father, Robert Autrey Sr., also a construction worker, left the family when Wesley was a toddler, and while his devout Christian mother, Mary, never divorced him, Wesley hasn’t seen his father’s face for 30 years.

Wesley joined the Navy at 17; had a son, Wesley Jr., now 33, whom everyone calls Boo; and had his two daughters, Shuqui, now 6, and Syshe, 4, with a different woman, who left him when Syshe was a baby. Wesley says he would have married her, but she wasn’t interested. “I thought we had a great thing.” He’s determined to support his kids the way his father never did. “The world looks at black men as deadbeat dads,” he says. “But that’s not me.”

After the Navy, Wesley worked for the Postal Service, then switched to construction. Recently, he’d been working for an outfit called T&S Management on a school project in Williamsburg. A shop steward in the Local 79 Laborers Union, Wesley had achieved a certain amount of seniority but was still living paycheck to paycheck. To varying degrees, he supports not just the girls but also his mother, Mary, a retired school-cafeteria worker; Boo’s daughters, Jéahni, 10, and Wesli, 1; and his sister Lucile’s three sons—Erroll, 28, Darius, 18, and La-la—and Quiana’s 2-year-old boy, Keyon.

Wesley’s life of quiet working-class anonymity came to a full stop on January 2. What happened that day has already taken on the quality of legend: the man with the seizure on the platform; Wesley’s shout to a stranger to watch his daughters and his dive onto the tracks; the split-second decision to grab the man and roll into the 21-inch gutter between the bottom of the train and the rails; the train’s abrupt halt, its first five cars passing over the two men; the twenty-minute wait for the MTA to cut the power to the third rail. On Letterman, and later on Ellen, Wesley explained why he did what he did. “Fool, you got to go in there,” he recalled thinking. (“I like that your mind called yourself a fool,” Ellen said.)

Had Wesley ever given any hint that he was the type of guy who’d jump in front of a speeding train to save a stranger? No, but to those who know him best, his act of selflessness wasn’t really surprising, either. “We always knew he was this great guy,” Linda says. “The world is just getting to know the brother we knew all along.”

It took time for Wesley to recognize the magnitude of what had happened to him. At first, he wanted to go straight to his job in Brooklyn. “I didn’t think nothing of it,” he says. “If anything, I thought it was going to make the paper, but that would probably be it. I had a family to support and maintain, and in construction, if you don’t go to work that day, you don’t get paid.”

As soon as he was outside of the subway station, he realized this was bigger. The News and Post reporters were wrestling over who got to drive him to the hospital. Inside Edition and CBS wanted him to go back to the station and reconstruct what happened. Within a day, Letterman, Ellen, Oprah, Charlie Rose, and Montel were calling. Hillary Clinton wanted to make a resolution on the floor of the Senate commending him. Trump sent his check. The MTA offered a year’s worth of free subway rides. One guy stopped him on the street and handed him a $10 bill.

“People wanted to hug me, they wanted to kiss me,” Wesley says. “It was an honor and a privilege to save a man’s life.”

He did Letterman, then flew with the girls to L.A. for the Ellen taping. The show put him up at the Sheraton Universal under an assumed name—Clark Kent. There was Disneyland and the Universal Studios tour for the girls, and babysitting so Wesley could go out on the town. On the show, he got the Jeep, the Nets tickets, and the hello from Beyoncé. The girls got free iMacs. “These are usually the people I see on TV when I’m sitting in the living room,” he says. “These awards, and the gifts me and my kids were getting? It was all good.”

At the State of the Union, Wesley hung out with the president in the greenroom. “We took pictures and laughed,” he says. Wesley’s a Democrat, but “didn’t get into the political thing. I’m an honorably discharged veteran. He’s the president of this country.”

Soon enough, though, there were problems. The five-minute walk from his apartment to the subway took twenty minutes now. People stopped him for pictures, hugs, and solicitations for donations—“I need, give me, I want,” Wesley says.

On January 9, when Wesley came home from the Ellen taping in California, he wanted to go back to work (he’d taken what he had intended to be a brief leave of absence). But there was too much to do. The American Stock Exchange wanted him to ring the opening bell on January 11. Spitzer wanted him on the 16th. The union local was honoring him on the 17th. His niece Quiana grabbed him by the arm. “Uncle Wesley,” she said, “I think you might have to realize that the construction worker—he died on the 2nd. There’s a new you. The public wants this new you.”

Wesley’s new life started to feel like a job, and one he wasn’t well prepared for. “It’s scary. I’m not used to this constant fame. I have people pushing me straight in front of a podium with a thousand eyes on me. Everybody’s looking at you and wondering, What is he gonna say?”

Wesley became exhausted. He told Linda he lacked time to savor even a little of his good fortune. His new life was cutting into his weekends with the girls. “They don’t like that,” he says. “I don’t either. I try to explain, ‘Daddy’s got kind of a new job, and I’m trying to make things happen and maybe get a house and a better way of life.’ But they don’t understand.”

He started to worry about money. You can’t pay the rent with a Jeep. And given the value of some of the gifts, the IRS would be watching. A friend at the union told him people could sue him now. His custody and support arrangement with the girls’ mother could be called into question. He might have to think about setting up tax shelters, and trusts for the kids. “Some people think I’m a millionaire,” he says. “So I’m a little worried about my own life and even worried about my kids, you know—someone might try to kidnap them.”

Women were running up to him in bars, plopping into his lap—but fame complicates that, too. On Valentine’s Day, he got a call from a woman who dumped him fifteen years ago. Without skipping a beat, he asked where she’d been the last fourteen Valentine’s Days. “So it’s like that?” she asked. The conversation trailed off.

At the end of February, Wesley heard from Robert Autrey Sr. for the first time in three decades. His father had been living in Pensacola, in sporadic touch with Wesley’s mother but never with him.

“He had a mild heart attack,” Wesley says. “He ended up in the hospital, and his sister called my mom’s house, and I picked up the phone.”

Wesley called his father at the hospital. “I don’t hold no grudges.”

What did his father say?

“That he was happy for me doing what I’d done, you know?” Wesley pauses. “Then him, like everybody else, ‘I need, I want, give me.’”

“Never once did he say, ‘Are you all right? Are the little girls okay?’ He just said, ‘There’s a family reunion coming, and if you’re coming, bring me some of that money you got.’ That’s how that went.”

The day after the State of the Union, Wesley attended some meetings in Washington. He had decided he needed some professional help to manage his affairs, and his older brother, Robert, an accountant for FEMA, had found him a lawyer, James McCollum, and an accountant, Robert Davis, who in turn had recommended a PR consultant named Doris McMillon. McMillon told him she saw Wesley becoming a motivational speaker. She also had endorsement ideas. “I contacted the president of Subway to talk about maybe using him as a spokesperson,” she says. “You know—‘The next time you stop at Subway, pick up a hero.’”

Making money off his heroism had never been a priority for Wesley. But the president had just saluted him on national television, and he started to wonder if failing to capitalize on what happened wasn’t noble but foolish. It had been almost four weeks since Wesley had taken home a paycheck. He’d paid some bills but hadn’t even bought a new suit for the White House. What kind of a son and father would he be if he didn’t make the most of this? “I wanted to surprise my mom with a house,” he says. “There’s a lot of things I wanted to do. There was a possibility of that happening if a book or movie thing jumps off. And I’m dying to just get a house for me and my family.” He laughs. “And my dream car is the Bentley coupe. I can’t park it on the street. So I need the house first.”

McMillon accompanied Wesley to appearances on CNN and Fox News Channel, but when he came home from the Super Bowl on February 5, he decided he needed a new management team. “Somebody from New York,” he says. “Somebody that I could touch base with like that.”

The night after the Super Bowl, Wesley met his new team—and started his trip down the rabbit hole.

At different times in his life, Mark Anthony Esposito says, he has worked as a celebrity photographer, an Internet mini-mogul, a trial consultant, a Formula 1 race-car driver, a documentary filmmaker, a licensed investment banker, a rock and blues musician and music producer, an unproduced screenwriter, and an unpublished novelist. He also says he has a Ph.D. in divinity. He is in his fifties and solidly built, with aquamarine eyes and a tightly wound, slightly unhinged affect—Joe Pesci with a mod haircut.

On February 5, the day after the Super Bowl, Wesley was a special guest at the Citizens Committee for New York’s annual gala at the Waldorf-Astoria. Ray Kelly, Pete Hamill, Wynton Marsalis, and David Dinkins were there. So was Mark Esposito. He says he was there as a journalist, shooting a video documentary about another honoree. But he knew who Wesley was. He’d been following his story with something of a proprietary interest. Ever since the London Tube attacks, Esposito says, he had been fiddling with a screenplay about terror on the subway. He’d spent some time in Hollywood years earlier, taking a two-day filmmaking course. Now he had the idea to use Wesley’s true-life story as a jumping-off point to make his project more marketable. He introduced himself briefly to Wesley, but his partner, Diane Kleiman, did most of the talking that night.

In her mid-forties, with a striking head of long red hair, Kleiman is a former Queens criminal prosecutor turned Customs agent who is best known for declaring herself a whistle-blower against corruption and lax security in the U.S. Customs Department. Fired in 1999, she spent several years speaking out about her allegations (she was the subject of a 2003 profile in this magazine). Last year, Kleiman met Esposito through a mutual friend, and the pair began working together. Kleiman is a member of the New York bar, and Esposito is not; he has experience in the entertainment business that she lacks. In the past year, Esposito and Kleiman say they’ve worked on behalf of a Korean singer named Jung Min Kim, a Manhattan church that was in a lease battle with its landlord, and a doctor who was accused of sexual harassment. That night, after making her way past a throng of well-wishers, Kleiman introduced herself to Wesley.

Kleiman’s credentials seemed impressive enough to warrant a meeting, so Wesley agreed to host one. On Friday night, February 9, Esposito and Kleiman went to Quiana’s apartment in the Bronx to make their pitch. Over the course of the five-hour visit, Esposito presented himself as a show-business veteran who’d worked with Bruce Willis once and made deals in Hollywood as a matter of course. He was energetic and aggressive: Wesley wasn’t just a news story, he said—he was a commercial and intellectual property that could and should generate revenue. Wesley had to make the transition from hero to brand, and Esposito said he and Kleiman were the ones who would take him there. Wesley liked them, and decided to work with them. “They seemed real,” Wesley says. “They said they can make stuff happen.”

Esposito and Kleiman both say that they brought with them a four-page contract for Wesley to review. Wesley now disputes this, saying he never saw a contract that night. That following Monday, Wesley and the girls were expected at the White House again, for the Black History Month celebration. They agreed that Mark and Diane would join him there. Wesley was reaching what could be the height of his public profile. The time to strike was now.

For several weeks prior, I had been talking with Linda about interviewing Wesley for this story, and she had agreed that I could shadow Wesley in Washington and interview him there. On Saturday morning, I called her to finalize the arrangements, but she asked me to speak with Wesley’s new lawyer, Diane Kleiman—“just as respect.”

When I called Diane, she spoke of Wesley as if he were a stray puppy who needed saving. The people around him at the Waldorf “were like leeches,” she told me. “He was inundated. He looked like a fish out of water. I went up and said, ‘If anyone asks you for money, they should be paying you money.’”

Diane told me she was fine with my interviewing Wesley in Washington, but a half-hour later, she called back. She said Wesley would now cooperate only if the magazine guaranteed him the cover, a minimum word count, a particular release date, final approval of the text, and the payment of expenses. These conditions, she said, were articulated by her partner, “executive Mark Anthony Esposito,” whom Wesley would require to be with him at all times during the interview.

I called Mark. “Wesley is like a Hollywood star or athlete,” he said. “Wesley has signed over intellectual-property rights for film and video.” To do this story, Mark insisted, Wesley would need some sort of compensation and control over the final product.

I told Mark his demands weren’t realistic—that it’s against the magazine’s policy to guarantee its subjects covers, show them the story first, or pay them. He laughed and said he’d already lined up major magazines that were willing to pay; at one point, he threw around the figure $100,000. “Everybody pays something,” he said.

Before long, though, Mark radically lowered his price: He’d grant me access to Wesley, he decided, if I would pay for plane tickets to Washington for him and Diane. When I said the magazine couldn’t do that either, he said, “How about train tickets?” When I refused that, Mark vowed never to allow me access to Wesley. And if he didn’t like what I wrote, he said, he’d sue me. Then he hung up.

I called Diane. She tried a softer tack. “We didn’t think we were asking that much from you,” she said. “Even if you took $1,000 out of your pocket and paid us, and New York Magazine wouldn’t pay you back, this would be a big story for you. It would sell thousands of copies.” But then her tone turned: “We’re gonna be down there, and Mark is gonna be all over you if you try to get close to Wesley.”

Linda got a call from Mark on Sunday. He was furious, she says, that she’d considered letting Wesley talk to me without compensation. “It was like he was the husband and I had just burnt the pork chops,” Linda says. She started having doubts about Mark. “We’d have doors shutting in my brother’s face, opportunities shedding, because you’re showing him this snub-nosed, I’m-better-than-you, reach-me-through-my-lawyer attitude. My brother’s not like that.”

That Monday morning, Wesley woke up at his brother Robert’s house in Washington and realized he’d forgotten to bring Shuqui and Syshe’s dresses. The closest mall didn’t open until 10 a.m., and the family needed to be at the White House shortly after 12:30 p.m. He dashed to JCPenney and bought two matching canary-yellow dresses with stockings and shoes, then hightailed it back to Robert’s. “I think better when I’m on my feet,” he says, “just like I was thinking when I saved Cameron.”

When he returned, Mark and Diane were at the house. They presented Wesley with the four-page contract. He had to get to the White House right away. Wesley signed the contract without reading it, and they left. “They were rushing me,” Wesley says. “The word was, ‘If we don’t hurry up and sign this, Wesley is going to be yesterday’s news, because when this Sean Bell case hit, that’s gonna knock you out of the box, so we need to do this—we need to sign these papers.’” (Mark and Diane insist Wesley had all weekend to review the contract and that he was eager to sign it.)

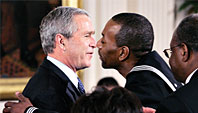

In the gilded East Room of the White House, Wesley stood beside Condoleezza Rice, Charlie Rangel, two space-shuttle astronauts, and a football coach. “I told him, ‘You’re a hero!’” the president said to the assembled guests and media. “He told me, ‘No.’ I said, ‘Wesley, I disagree, as do millions of our fellow citizens.’” Wesley, dressed in a Navy uniform, kissed the president on the cheek; the picture was picked up everywhere. Then, on Mark’s instructions, Wesley grasped the president’s arm and turned him so his back was to the audience—out of view of the camera crews—and asked Bush to pose for some snapshots with Wesley’s mother and the girls.

Mark took those pictures with his own camera. They’re his intellectual property. A week after the White House event, Mark applied to trademark the phrase “subway hero” and “subway angel American hero,” then registered the same phrases as book and movie properties with the Writers Guild. But those trademarks and titles aren’t registered in Wesley’s name. They’re in Mark’s.

The contract Wesley signed that morning in Washington wasn’t a management contract or a retainer. It was a partnership agreement, entitling Wesley to just 50 percent of “any revenues from any and all commercial exploitation” of his “name, personality, story and reputation” in the next three years. The other half would go to any potential producing partners, including Diane Kleiman and Mark Anthony Esposito.

On February 19, I had lunch with Mark and Diane at Odeon to try again for access to Wesley. (I’d covered the Black History Month event with a press pass from the White House.) Mark began the lunch by sharing more of his personal history (“I saw Jimi Hendrix have sex!” he said—twice), but he spent most of the meeting detailing the ways he had dreamed up to make money off the Subway Superman. He said he came up with the idea of dressing Wesley in a Navy uniform so that Bush would gravitate toward Wesley at the Black History event. He said he made sure that the family kept their backs to the media so that he had exclusive pictures. He also said that he and Diane believed that as a black celebrity, Wesley could keep his name out there all through 2008 by dangling the prospect of his endorsement in the presidential race. Mark’s plan: Come out for Hillary now, then switch to Obama next year, citing racial loyalty. Then Mark and Diane hinted that Wesley was concealing a secret about his personal life that would make his story even more marketable. They wouldn’t reveal what it was, they said, until the right offer came along.

A few weeks later, on March 1, at yet another meeting to wrestle over access, Mark suddenly seemed to imply that access was no longer a problem. I was free to talk to Wesley anytime, he said. He spoke as if he and Diane had never been an obstacle.

What I came to find out a few days later was that Mark and Diane had been fired earlier that week. Wesley and Linda had come to believe that Mark and Diane weren’t acting in Wesley’s best interests, and that the 50 percent share they had staked out for themselves was unreasonable.

But Mark didn’t seem to care about being let go. He had his trademarks, and he and Diane had their contract. “Wesley could be living or dead now, it doesn’t matter,” Mark told me. “He is an intellectual property now, and we are protecting our interests.”

On March 22, Wesley filed court papers against Esposito and Kleiman, accusing the pair of embarking on an “unconscionable scheme” that began at their first meeting. The lawsuit alleges that when Wesley met her at the Waldorf, Diane had said she wouldn’t charge for her legal services; that she falsely said she was an entertainment lawyer; that the duo promised nothing would be done without Wesley’s input; that they sprung the contract on him in Washington and took advantage of him. The suit also argues that Diane signed the contract a day before everyone else, giving Wesley the impression that she had reviewed it to make sure his best interests were represented—and that Diane misrepresented herself as Wesley’s attorney when in fact she was signing on as his business partner. He also claims that Diane never mentioned a section of the contract that makes Wesley pay for Diane’s legal expenses in any arbitration.

Finally, the lawsuit claims Diane and Mark were never working in Wesley’s best interests, citing two examples: that Diane tried to get a public elementary school to pay for an appearance by Wesley, and that Mark and Diane tried to get this magazine to pay for their airfare to Washington.

The day the lawsuit was filed, I called Diane. She was furious. She’d been taking calls from reporters all day. “His argument is, ‘I’m an uneducated black man who didn’t read the contract so the contract shouldn’t apply to me because my attorneys are smarter than I am’?” she asked. “I don’t need this shit in my life right now.” She insisted Linda was the one who wanted to charge the elementary school. “She told me, ‘Wesley don’t do nothing for free.’” (Linda denies this.) Diane also denies that she had a conflict of interest—she says it was clear she was his business partner, not Wesley’s lawyer. She also revealed that she was no longer on speaking terms with Mark. Now both Mark and Diane say they’re considering filing countersuits.

I asked if she thought 50 percent was a little too much to ask of Wesley. “It is actually extremely low,” she said. “Look at recording artists—they have all these people around them taking fees. In the end, they get something like 3 percent. Besides, Wesley didn’t have to do any work. He wasn’t paying any money. If we didn’t cut the deal, we didn’t get paid. So how doesn’t he benefit from that?”

I decided to ask Diane what the secret of Wesley’s life story was—the piece of his bio they were hanging on to, to exploit for a book or movie. She exploded. “There was nothing. We were making it all up. It was gonna be taking some of the stuff—like a fictional-type movie—and just taking some aspects of it and try to sell that into something that would make money. He had fifteen minutes of fame. There was nothing more than that. Nothing.”

The next day, Mark invited me to his apartment-office in Tribeca. When I arrived at noon, the TV was tuned to NY1 with the sound off. Every ten minutes, the same B-roll of Wesley would flash onscreen accompanying a report about the lawsuit. After a quick tour of his memorabilia cabinet—featuring photos of Bruce Willis (Mark directed a promo for the original Die Hard) and porn star Taylor Wayne (“She’s a friend,” he said)—Mark showed me a producer contract from fifteen years ago he signed with a singer. “I’m not some con man who read about Wesley in the news and jumped on this,” he told me. Then he showed me the trademark certificate for the phrase “subway hero” in his name. “I don’t represent Wesley,” he told me. “I am a partner with Wesley. He doesn’t own any of the intellectual property. I do.” Divorcing Wesley from Mark, Mark said, would cut Wesley out of any deal.

Mark has already written a movie treatment, which he showed me—Wesley’s tale, tarted up to be a Brad Pitt or Tom Cruise vehicle. It starts with an ex–Navy man named Wesley who saves a stranger on the subway tracks when a terrorist named Abdul stages an attack and kidnaps his children. In this version, the kids are a boy and a girl, and they turn out to be secret agents. Then they have electronic devices implanted in their heads. Wesley foils the plot in the end—and gets the girl too.

“He sues, he doesn’t get paid,” Mark said. “I’m so happy he sued it’s not even funny! He’s done everything wrong. Every single thing. They think they’re rap artists, and when the time comes they’ll not pay the man and that sort of thing. And when the time comes, he’s gonna be broke. He can leave. But he has to pay.”

On my way out the door, Mark was laughing. “I don’t mind even getting slammed in the press. Getting slammed helps my material! Don’t be surprised if Wesley and I are having dinner tonight. We might be doing this for the publicity! Don’t underestimate me. Don’t underestimate me!”

It’s Easter Sunday, three months since Wesley jumped onto the tracks, and the whole family is gathered at Mary’s tiny apartment on 135th Street. Later, there will be a turkey, but right now, Keyon and little Wesli are wandering underfoot; Darius is singing in his fine tenor voice; Wesley is grabbing a cigarette in the hallway with Linda and Quiana.

Wesley’s getting used to being recognized everywhere he goes now. “When you’re in the public eye, you can’t be mean,” he says. “I love people, you know what I’m saying? That’s why I did what I did for that man that day.” There are still scores of requests for appearances and interviews, but he and Linda have set limits now: No more than one event, appointment, or interview a day. The rest of the time, Wesley can rest, be with his family, be anything other than the Subway Superman.

Short of Beyoncé’s walking through the door, the woman thing is on hold, too. “I’m in no rush at the moment. I’ve been in the Navy, so I know how to do without a woman. You just have to put it out of your mind till you hit port.”

With Easter supper waiting, Linda says she is focusing on the spiritual rewards of what Wesley did—what he taught us all. “Wesley grabbed Cameron—grabbed him, touched him, squeezed him. We don’t do that anymore. Computers, cell phones, Palm Pilots—we don’t touch. I think there’s a message in that—bigger than a movie deal, book deal, you know what I mean? There’s a human message for all of us.” Wesley says he too wants to use his fame “for some good.” He is thinking of starting an after-school program for kids in his neighborhood.

But Wesley’s still not getting a paycheck, and pressure is still building for him to make money. “I’m on a leave of absence, but I have bills. I need an income. There’s fourteen, fifteen of us. I’ve got to make something happen.”

The catch is, the lawsuit hangs over everything. Signing a movie or book deal now could mean Mark and Diane would get half of the proceeds. Any lawsuit takes time, but now Mark and Diane are at cross-purposes, making everything, including a possible settlement, that much more complicated. “You got to have lawyers to watch the lawyers,” Wesley says (he says he’s happy with his new lawyers, who were recommended by his union). “Once the papers were signed, Mark and Diane just wanted to knock my family out. Everybody that me and Linda were on good terms with, they didn’t like. That didn’t seem ethical. And I didn’t feel good about them wanting to keep that 50 percent. To me, that’s greed. They were too greedy.”

About the best Wesley can do for now is keep his name out there for as long as he can. The family is appearing soon on Deal or No Deal. The producer of Heroes is talking about a walk-on. Subway is interested in the hero thing, too. Maybe he’ll be their next pitchman. Oprah still wants him—and has asked him to contact the Hollopeter family to see if Cameron is ready for a tearful reunion. No dice, yet. Wesley has visited Hollopeter in the hospital twice and has stayed in touch with his family on the phone, but Hollopeter has shown no appetite for being in the public eye.

I ask Wesley if he ever wishes he could have somehow saved Hollopeter but still remained anonymous himself. Which life does he prefer, the life of Wesley Autrey or the life of the Subway Superhero?

He’s silent for a long moment, then laughs. “That’s a Catch-22,” he says. Then he settles on an answer. “This is better. Now I’ve got a chance, you know?”

Wesley didn’t save a life to become famous, of course. It’s just that now, what’s the use of pretending none of this happened? “I feel like the black prince of America,” he had told me earlier. “I just don’t have the money yet.”

Recently, Wesley had business cards printed up. He hands them out everywhere he goes now. They read WESLEY AUTREY SR., “SUBWAY HERO.”

THE ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN

An anatomy of overnight celebrity.

January 2

Wesley talks with reporters after jumping on the subway tracks to save the life of 20-year-old Cameron Hollopeter.

January 3

Wesley recounts the rescue at the 137th Street subway station; receiving a $5,000 check and scholarships for his two daughters; and holding his Post cover.

January 4

Wesley receives the Bronze Medallion, the city’s highest civic award, from Mayor Bloomberg; accepting a $10,000 check from Donald Trump; and appearing on the Late Show With David Letterman.

January 8

Goes on set with Ellen DeGeneres.

January 11

Wesley rings the opening bell at the American Stock Exchange.

January 23

Wesley acknowledges George Bush after being honored at the State of the Union address.

February 10

Wesley soaks up applause at a Washington Capitals game.

February 12

The president hugs Wesley as he celebrates Black History Month in the East Room of the White House.

April 3

A free 2007 Jeep Patriot.

SEE ALSO: The Adventures of Superman