Someday, around a year from now, one of your friends is going to say to you, “Let’s go to the High Line.”

Now, this person might be talking about the High Line park, the well-publicized ribbon of greenery that’s being constructed on an abandoned elevated rail line in far west Chelsea, running north from Gansevoort all the way to 34th Street. Or your friend might be referring to the High Line neighborhood: the new skyline of glittering retail spaces and restaurants and condos, designed by brand-name architects like Frank Gehry and Jean Nouvel and Robert A.M. Stern, with names like the High Line Building and High Line 519 and HL23. Or your friend might mean the High Line Terrace and Lounge in the new condo tower at 245 Tenth, which promises prospective residents views over the High Line, along with “polished cervaiole marble floors.” Or maybe your friend wants to go to the Highline Thai restaurant on Washington Street, or the High Line Ballroom, a recently opened concert venue, which, starting May 9, will be part of the High Line Festival, an event curated by David Bowie and showcasing such snazzy right-now artists as Ricky Gervais and Arcade Fire. Granted, a few of these events will be barely within yodeling distance of the High Line—you know, the railroad—but no matter: Two of the festival’s producers, Josh Wood and

David Binder, chose the name less for a proximity to the High Line than for their philosophical alignment with the park. “The High Line is very much about aesthetics and design,” says Binder. “We’re trying to be as well.”

“Everyone in New York City has been so supportive of the High Line,” says Wood. “It’s probably the one public-works project that no one has anything bad to say about.”

Given all this activity, it’s probable that, like most New Yorkers, you’ve already heard of the High Line. It’s also probable that, like most New Yorkers, you’re only vaguely aware of what exactly it’s going to be. Maybe the last time you thought about it was in 2003, when Friends of the High Line—the nonprofit group that’s been fighting doggedly to save it for the past eight years—held an open design competition for creative suggestions as to its ultimate fate. The results were exhibited at Grand Central Terminal, and submissions ranged from a permanent nature preserve to a roller coaster. One of the winning entries was a 22-block-long elevated swimming pool.

So here’s an update.

First, the short version: The High Line is a brand-new park. In the sky.

Now, the longer, slightly more complicated version: The High Line is, according to its converts (and they are legion), the happily-ever-after at the end of an urban fairy tale. It’s a “flying carpet,” “our generation’s Central Park,” something akin to “Alice in Wonderland … through the keyhole and you’re in a magical place.” It’s also the end-product of a perfect confluence of powerful forces: radical dreaming, dogged optimism, neighborhood anxiety, design mania, real-estate opportunism, money, celebrity, and power. In other words, it’s a 1.45-mile, 6.7-square-acre, 30-foot-high symbol of exactly what it means to be living in New York right now.

But first, let’s start with the park.

If New York were in the practice of erecting statues to living people, you could make a good case that Joshua David and Robert Hammond should be cast in bronze tomorrow. You can almost picture their monument, too—perhaps the two of them smiling, arm in arm, hard hats on their heads—which you could unveil next spring at the projected opening of the High Line park. Or, instead, you could place that statue in the lobby of Craftsteak, the cavernous, warmly lit restaurant at the corner of Tenth Avenue and 15th Street, where I met Hammond and David for dinner on a recent rainy April night.

Walking along 15th toward Craftsteak, you’ll find as good a tour of the new Manhattan, pressed up shoulder to shoulder with the old one, as you’re likely to find. In one block I passed an auto-repair shop (“Foreign and Domestic”), the display windows of Jeffrey department store, a car wash right under the High Line, and a jam-packed opening at Milk Gallery, where well-dressed art-world attendees were lit up sporadically by the pop of flashbulbs. On Tenth, Escalades and limos sat idling with their blinkers on, outside Morimoto, or Del Posto, or Craftsteak, the massive restaurants drawing diners to their tastefully humble façades. As it happens (and this story has a lot of “as it happens” moments), Hammond, who is a part-time painter, has three of his works hanging in Craftsteak, and a huge painting by Stephen Hannock of the High Line, as seen from a nearby rooftop, is displayed in the restaurant’s main dining room. “We took him up on the building to help him get that vantage point,” says Hammond. “And we used an old photo taken from the same place in the thirties as a reference. It’s amazing that, besides the Gehry building”—which is visible in the painting as a skeletal shell full of lights, mid-construction—“how little in the neighborhood has changed.”

Rendering: Hayes Davidson

Over the years, there have been other efforts to reimagine the High Line as a public space—as early as 1981, the architect Steven Holl proposed a project preserving the railbed, which he praised as “a suspended green valley in the Manhattan Alps”—but these were all lost in legal wrangling or dismissed as the idle noodlings of urban fantasists. Where Hammond and David have been successful, though, is in assembling a glamorous coalition of tastemakers, the right people at the right time, and convincing them that a neighborhood green space could be a win-win for everyone involved. From the beginning, they presented the High Line as a kind of industrial-chic anchor, a sculpture in the sky, in a blossoming arts district. Their save–the–High Line effort, which at first glance seemed impossible, now, in hindsight, seems inevitable, given how the High Line can appeal both to people’s rediscovered nostalgia for the city’s iron-age past and to that tingling, money-flushed excitement for tomorrow, in which every inch of Manhattan will be reclaimed and converted into an impeccably designed playground.

Together, the pair is unfailingly gracious and quick to deflect praise. They refuse to even really acknowledge what is essentially their victory lap. They share a bemused ambivalence toward all the profiteers now benefiting from the High Line’s prestige. Early on, they looked into trademarking the name “High Line,” but found they couldn’t, any more than you could trademark “Central Park.” Besides, they say, eight years ago, an overabundance of enthusiasm for the idea of the High Line was the least of their problems. David recalls an early City Council meeting they attended, along with socialite Amanda Burden, where their pie-eyed plan was so roundly ridiculed that, he says, “You really did feel like you were getting pissed on.” Then Burden rose to speak. “She rallied the most incredible response about how great it is that there are still dreamers in New York,” says David.

“Since when is dreamers a dirty word?” says Hammond.

It’s easy to see how, with their combined strengths, they went from stuffing envelopes in an apartment in Chelsea in 1999 to attending a groundbreaking ceremony in 2006 at which every politician within a hundred-mile radius—Hillary, Schumer, Nadler, Bloomberg—crowded the podium, smiling for the photo op. Hammond, who’s 37, used to work as a marketing and Internet consultant, and he pairs an artist’s eye with a salesman’s vigor for cold-calling contacts. David, who’s 43, is a former freelance journalist with a specialty in urban design, which came in handy while writing the High Line literature and eloquently articulating the group’s goals. They also share a strong interest in aesthetics. When I call them one day at their office and ask what they’re up to, David says, “We’re arguing about fonts.”

As it happens, Hammond and David met by accident, when they sat next to each other at a community-board meeting about the High Line in 1999. Both of them had hoped to connect with whatever Save the High Line movement was already organizing, only to discover that no such movement existed. After the meeting, they started talking and decided to form a group themselves. “Of course,” says David, “we didn’t realize we were stepping into a fight that had been in the courts since the early eighties.”

See, the High Line was built in the thirties to service the warehouses along the West Side. It replaced a Tenth Avenue train track that ran down the middle of the street and, with distressing frequency, ran down pedestrians. (The street was nicknamed Death Avenue.) No sooner was the High Line built, however, than train traffic slowed to a trickle, thanks to a double whammy of the Depression and the popularity of truck transport. The last train ran on the High Line in 1980, at which point it was more or less abandoned: a typical shard of industrial blight, left to rust and grow wild with weeds.

Conrail, the railroad that owned the High Line, wanted it gone. A consortium of local property owners, led by one of the area’s largest interests, Edison Parking, a company run by Jerry Gottesman, wanted it gone. The city wanted it gone. And the only reason it isn’t gone is that, essentially, no one wanted to pay to take it down. And so the High Line languished, untouched and off-limits, while legal battles over its fate smoldered for the better part of twenty years.

Which brings us to 1999, when Hammond and David met and formed Friends of the High Line. From the beginning, they knew they needed to invest their cause with a certain intangible downtown sexiness, to excite potential donors about the possibilities for this long-neglected piece of industrial detritus. They enlisted Paula Sher, a partner at the graphics firm Pentagram, to design a logo and a look for their literature. Then Hammond started hounding every notable and/or powerful person he could think of: gallerists like Paula Cooper and Matthew Marks, architects like Richard Meier, and the well-connected like Amanda Burden, who had a seat on the City Planning Commission. These efforts, of course, pleased no one who’d been entangled in the long battle to topple the High Line, least of all Gottesman, who was eager to build a FedEx depot on his property at Tenth and 18th. By this point, Mayor Giuliani had thrown his support behind the drive to demolish the railway. To prevent that, Hammond and David decided to sue. They needed $60,000 in up-front legal fees, so the Friends of the High Line held its first fund-raiser, in December 2000, at the Lucas Schoorman gallery in Chelsea. They sent out fliers, one of which ended up in the hands of Kevin Bacon and Kyra Sedgwick, who actually showed up at the party. As David remembers it, a newspaper also covered the event—and framed it the next day as a celebrity push to stop FedEx.

“They totally got it wrong,” says Hammond.

“But it was instant branding,” says David. “Just by luck, we were celebrity darlings.”

Gottesman, by the way, never did get to build that FedEx depot. That parcel is now destined to house a 35-to-40-story complex, developed by Edison Properties and to be designed, at last report, by Robert A.M. Stern.

Nearly everyone involved in the Save the High Line effort—from Gifford Miller to Amanda Burden to Edward Norton to Diane Von Furstenberg—will tell you about their hallelujah moment. The idea of a park on a railbed in the sky can be a little hard to get your head around, especially if your only vantage point is looking up from street level at its rusted, pigeon-shit-scarred underbelly. “But the moment Robert got me up there, I fell in love with it,” says Miller. “You’re in the clouds, as it were—on the level of the Jetsons.”

I first truly understood this phenomenon when I ducked through a hobbit-size door in the backside of a Tenth Avenue warehouse—and stepped directly out onto the High Line, between 25th and 26th Streets. Here, the railbed stretches off in both directions, resembling a lush, weedy boulevard unspooling over the city streets. I was accompanied at the time by Douglas Oliver, who owns the Williams Warehouse, along with a silent partner. A trim man in his early sixties, with curly, salt-and-pepper hair, Oliver was wearing a collarless black peacoat and a black-and-white ascot. Currently, his warehouse is used to store sets for soap operas; as we walked among the stashed sofas and upended, ornate lamps, he shouted to his superintendent, “Hey, Felix, where’s my favorite coffin?”

Then we all stooped through the door he punched in his back wall three years ago, and boom, there we were, on the High Line—a moment that felt like stepping through the back of the wardrobe, out into Narnia.

The High Line has always been closed to the public, so from the beginning, Hammond and David understood that—fancy brochures and professionally produced videos aside—they had to find a way to bottle and sell this hallelujah moment. A friend recommended they contact the photographer Joel Sternfeld, who had shot ruins in Rome. They invited him up for a visit. Sternfeld remembers his own High Line epiphany. “Suddenly, it’s green! It’s a railroad! It’s rural! Where am I?” he says. As he stood out on the railbed, mouth agape, Hammond whispered to him, “Joel, we need the money shot.”

Sternfeld worked on the project for a full year. “I could go up there anytime I wanted,” he says. “That was one of the greatest gifts of my life. I had my own private park.” On one afternoon, in 2001, he invited The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik to tag along, and Gopnik subsequently rhapsodized about the structure in a florid essay. “The High Line does not offer a God’s-eye view of the city, exactly,” he wrote, “but something rarer, the view of a lesser angel: of a Cupid in a Renaissance painting, of the putti looking down on the Nativity manger.”

As it happens, Edward Norton, the actor, whose grandfather was a visionary developer who helped save Boston’s Faneuil Hall, read Gopnik’s paean, and decided he should lend his name and support to the Friends of the High Line effort. He phoned them up and, later, became a public face for the group, appearing on Charlie Rose and speaking at events. “He’d say, ‘Look, there are a lot of people who want your money,’ ” Hammond recalls. “ ‘There are a lot of causes out there doing more important things—saving lives or educating kids.’ Then he summed it up in a way I always liked: ‘This is about optimism. This is about New York reinventing itself.’ ”

Now, standing on the landing of Oliver’s bricked-over loading bays six years later, you can hear the construction crews ten blocks south—that familiar sound of New York reinventing itself. The initial phase of the new park stops at 20th Street; Phase 2, from 20th to 30th Streets, likely won’t be done until 2009. Still, for Oliver, it’s not hard to envision the future. “I’m seeing a restaurant, maybe a gallery,” he says, then, gesturing to the loading bays, “All this could become glass.” He and his partner bought the building in 1978, for $75,000 cash down. Now he fields constant calls about selling. He’s been offered well over $100 million, but figures it’s probably worth more. He’s heard the building at Tenth and 15th that houses Craftsteak and Del Posto just sold for $150 million. Faith Hope Consolo, a retail specialist for Douglas Elliman, foresees a 12 to 15 percent rise in prices all across the neighborhood: retail, commercial, residential. Even modest properties are benefiting. A nearby space on West 21st, nestled literally right under the High Line, is currently up for rent. The broker also imagines a restaurant, a gallery. “It’s a really unique space,” he says. Ten years ago, he leased it to the auto-body shop for $20,000 a month. Now he’s asking $70,000 a month.

Oliver doesn’t envision selling, however—he’d rather partner with a gallerist or a restaurateur, do something “in the spirit of the High Line.” He recently spent $2 million to upgrade the building’s façade. Now he’d like to stick around to enjoy his good fortune. “These days around here, you see women in fur coats buying million-dollar paintings,” he says. “When I bought this place, the women in fur coats around here were usually men.” He was an early supporter of the Friends of the High Line, making what he describes as a “substantial” donation. “A lot of good’s come out of the High Line,” he says. “This is a gold mine. The landlords should be thanking them.”

In fact, even before the city announced, in June 2005, that it had approved the rezoning plan that would preserve the High Line and allow for new construction projects all along its length, savvy real-estate speculators had grasped the potential of a “High Line” neighborhood. The developer Alf Naman, who’d been circling the area since the mid-nineties, bought up about a half-dozen properties. “I saw what happened in Tribeca,” he says, “and I didn’t want to miss out here.” He’s now developing three properties, including a hotel that will look out directly on the High Line and a condo tower by architect Jean Nouvel at 100 Eleventh Avenue, with a bistro-style restaurant on the main floor. (Danny Meyer is rumored to be the eventual tenant.) André Balazs, the hotel impresario, who was also an early donor to Friends of the High Line, purchased two plots of land on either side of the track, near 14th Street, where he’s building a Standard Hotel. “We started construction before it was even clear who owned the High Line,” he says—a gamble that he says now is “looking brilliant.” His hotel will literally straddle the High Line, and in his ideal vision, Balazs will offer his guests direct access through a stairway from the hotel to the park—though the details of who can or can’t build entrances to the High Line, and what exactly those entrances might look like, and whether you can put patio chairs or café tables out on the High Line grounds, are all still being hashed out with the city. But Balazs is confident he’ll get his staircase. “This is going to happen,” he says.

Farther north, the architects Della Valle Bernheimer are building two new projects, one on 459 West 18th and one at 245 Tenth Avenue, and Jared Della Valle is still looking for other opportunities. “But there’s been a frenzy in the neighborhood,” he says, “to the point that properties are trading at a rate that doesn’t make any sense.” Some mid-block parcels are still coming on the market, as leases run out or reluctant sellers are swayed by the arrival of the money truck. “But the majority of the A locations”—meaning ones right on the High Line—“have already traded hands.” He mentions the one crown jewel that’s still available—a huge lot at 18th and Tenth Avenue, right next to Gehry’s building. “We put an offer on that,” he says, “but we dropped out when prices went through the roof.” Prices in the neighborhood have gone up 30 percent in the last year, and are now among the highest in the city, with some lots going for over $500 a developable square foot. I ask Della Valle how those numbers compare with other Manhattan neighborhoods. He pauses. “There’s not much out there. You’re talking Central Park West.” For developers, investing at those prices, he says, is “like Russian roulette, except there are four bullets in the gun instead of one.”

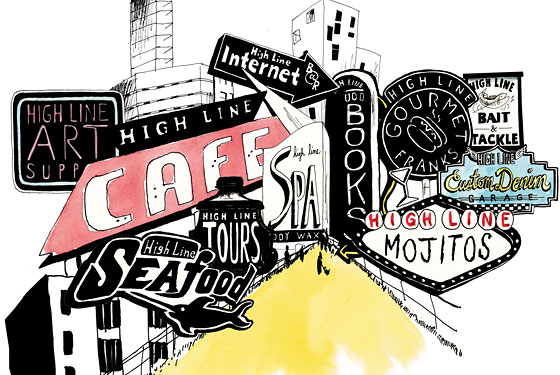

Of course, far West Chelsea, with its mix of low-income housing and hot-spot restaurants and galleries and supersize clubs, has long been a neighborhood in transition. But the arrival of the High Line—it’s a park! In the sky!—offers developers a glamorous, one-of-a-kind amenity to pitch to millionaire buyers. Balazs, for one, is confident he’ll recoup his investment, but he’s not so sure about those who got there after him. “There are parts of the High Line that have charm, and other parts where it’s really nothing more than a piece of steel running through a piece of property,” he says. “But the mere phrase High Line is now a buzzy phrase. So I think you’re going to find all sorts of worthless developments going up, where people will happily tag the name ‘High Line’ to their project, hoping to give an otherwise lackluster project some sizzle.”

There are three central ironies to the story of the High Line. The first is that, for twenty years, local property owners were the main opponents to the park-conversion plan. At the height of his battle with Friends of the High Line, Edison’s Gottesman launched a propaganda campaign. “They had one flyer that said, ‘Money doesn’t grow on trees, and last we checked, it isn’t growing in the weeds of the High Line,’ ” says Hammond. “Now the irony is, money is growing in the weeds of the High Line—for them, and they’re picking it.”

The second irony is that, despite all the good vibes and upbeat statements from politicians at every level of the food chain, the stretch of the High Line that runs from 30th to 34th Street, fully 30 percent of its total length, is still in danger of demolition. Its fate is more or less in the hands of the MTA, which owns the Hudson Rail Yards. The MTA wants to sell its land for maximum profit and, by all indications, is not planning to make preservation of the High Line a condition of the sale.

The last irony is that the rest of the High Line—the one that Sternfeld photographed, the one that sparks that reliable hallelujah moment in the hearts of one goggle-eyed visitor after another—isn’t being saved at all. In fact, it was doomed from the start. Hammond and David knew that, in order to rally initial support, they had to convince people that the High Line was worth preserving in the first place, and they did so with Sternfeld’s bucolic images of an untouched pasture in the sky. But now the High Line, by necessity, is being stripped to its foundations. The Friends of the High Line spent a long time trying to figure out if that original park could be preserved, but it just wasn’t feasible. “That landscape existed because nobody could go up there,” says David. “And to get people to go up there, you have to do something different.” The architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, who are designing the new park along with landscape architects Field Operations, initially submitted a plan using “flyovers”—basically, plankways that would sit over the existing High Line flora—but discovered there was too much industrial contamination on the site. “To let people go up there,” says Ric Scofidio, “we had to strip it.”

So when the new park opens next year, it will offer visitors a very different, essentially artificial experience. The park will ideally evoke the feel of the old, untouched High Line, which is now preserved only in Sternfeld’s loving photographs. Many of the same plants are being planted, some of the old rail track will be reused, and a concrete pathway will gently nudge visitors toward a similarly meandering experience as they travel from one end to the other. As for the new buildings around the High Line, that’s out of Scofidio’s hands. “Right now, a lot of the buildings along the High Line have blank walls, because there’s been no reason to open to the High Line,” he says. “If those blank walls suddenly become filled with balconies and windows, that’s going to change the atmosphere. But that’s going to happen. You can’t avoid it.” Hammond and David are more upbeat about the flourishing neighborhood. They react to concerns about all the radical changes with only a slight hint of weary defensiveness—like two researchers who’ve spent ten years trying to crossbreed a unicorn, and now they have to endure complaints about all the hot-dog stands popping up around the unicorn’s stable. “It’s very important for me to understand everything that’s happening here in the context of this much broader movement happening all over the city,” says David. “It’s just happening in a slightly different way here, because of the High Line.”

I asked Sternfeld if, having spent a year documenting the High Line in his own private park, he now felt mournful about its passing. He said, “Yes, no question about it. I feel really sad. It was beautiful. It was perfect. It was authentic. I wish everyone could have the experience that I had. But you can’t have 14 million people on a ruin.”

Since the High Line that you’ll walk on a year from now isn’t going to feel like the High Line you couldn’t walk on a year ago, let me try to lay out for you what your future hallelujah moment might feel like. At the south end, near the meatpacking district, the Standard Hotel, with its maybe-or-maybe-not staircase, will rise, bowlegged, with its trademark upside-down signage, eighteen stories above the park. There will be a satellite branch of the Whitney museum nearby. From the street, you can ascend the stairs to the High Line park and head north along a pathway of interlocking concrete planks. You can probably even bring a dog—as it stands, pets will be allowed on the High Line, but not bikes. (“The Hudson River Park is a fast park,” says Scofidio. “We envision this as a slow park.”) In early designs for the park, slim and stylish visitors are illustrated wandering idly through the sculpted grounds, among such oddball imagined details as a cantilevered grandstand on which people are seated watching 2001: A Space Odyssey. (Those elements—the grandstand, a proposed “water feature” that would have featured an urban beach—have since been discarded.) And as you walk, from time to time you’ll stand above an intersection, where you can enjoy a unique, unbroken vista from one side of Manhattan to the other; basically, the view you might get if you could stand in the middle of the road, not get run over, and be 30 feet tall.

As for the rest of the view, you can expect a veritable Disneyland of starchitecture, with ten new buildings currently rising and roughly fifteen more in development—some with access right to the High Line, some simply hugging its edge; some scaled humbly to the surrounding historical blocks, some potentially as high as 40 stories, and some that are new buildings built on top of existing buildings, like crumpled crystal top hats. One of the new towers, at 200 Eleventh Avenue, will offer “en suite parking” to tenants (basically, an elevator that will take your car from street level and park it directly outside your apartment), pending community-board approval; Madonna’s rumored to be sniffing around. Another planned tower will tilt over the High Line, stooping slightly at its midsection like a butler ushering you through a door. And all of these buildings, as you pass them, will feature walls of condos and lounges and restaurants with windows full of people looking down from their sparkling new towers at the High Line, and you.

What you’ll get, in other words, is a thoughtfully conceived, beautifully designed simulation of the former High Line—and what more, really, do we ask for in our city right now? Isn’t that what we want: that each new bistro that opens should give us the feeling of a cozy neighborhood joint, right down to the expertly battered wooden tables and exquisitely selected faucet knobs? And that each new clothing boutique that opens in the space where the dry cleaner’s used to be—you know, the one driven out by rising rents—should retain that charming dry cleaner’s signage, so you can be reconnected to the city’s hardscrabble past even as you shop for a $300 blouse? And that each dazzling, glass-skinned condo tower, with the up-to-date amenities and Hudson views and en suite freaking parking, should be nestled in a charming, grit-chic neighborhood, full of old warehouses and reclaimed gallery spaces and retroactively trendy chunks of rusted urban blight? Isn’t that exactly what we ask New York to be right now?

Think of all the big, less attractive developments—Atlantic Yards, the Jets stadium, Moynihan Station, ground zero—that have foundered. Yet the High Line went from impossible dream to construction in under ten years. After 9/11, Hammond and David thought they were sunk—who would care now about an abandoned railbed? But instead the possibilities of the High Line caught people’s imagination and stirred their ardor more than ever—and why not? It’s a tabula rasa, sturdy enough to absorb whatever idyllic vision of the city you endorse. It’s pastoral, yet futuristic! It’s exclusive in its aesthetics, yet accessible to everyone!

Don’t get me wrong: It’s impossible not to cheer the efforts of two guys who started with few allies and spent eight years of their lives fighting for a brand-new park. In the sky! What a great idea! Who doesn’t love a park? And the High Line, as it existed, could not be expected to continue to run like a rusted bridge, untouched and unsullied, over the roiling crosscurrents of abundant money and development fever and relentless, transformative good taste—not in the New York we live in now, not in this city, where every parcel is coveted, every square inch monetized, even in the air. In order to persuade all the property owners to sign over their rights, the Department of City Planning, led by Burden, used the tool of allowing the owners to transfer their development rights to surrounding properties. Then they rezoned parts of West Chelsea to allow for new, larger developments. This plan includes provisions that will, in theory, encourage the mid-block galleries on the cross blocks to stay, in the hope that the galleries won’t be run out by new stores and residences, the way they once were in Soho. It’s a good plan. It even won an award. As Faustian bargains go, it’s pretty honorable, given that everyone—the preservationists, the developers, the neighbors, the weekend visitors—seems happy. For the most part. Well, almost everyone.

At Tenth and 18th, you’ll find La Lunchonette restaurant, which has been open there for nineteen years. By all rights, its owner, Melva Max, should be ecstatic about the High Line. From her front window, she has a beautiful view of one of the most visible stretches of the track. I point this out to her, but she can’t see it. All she sees is the 30-story condo tower she’s heard is going to rise in the vacant lot right across the street. “People say to me, ‘You’re going to be so busy, the restaurant will be full of people all the time,’ ” she says. “But I really don’t think these will be the kind of people who are going to walk out of their fancy buildings to come over here and have an omelette.”

Michael Sorkin, the architect and writer, who lives in Chelsea, is also in favor of the park. Who doesn’t love a park? “It’s going to be a great park,” he says. “But if it proves to be another really big nail in the process of making Manhattan into the world’s largest gated community, so be it. Let it be remembered for that.”

David hears those concerns and answers by pointing to Central Park: another entirely constructed landscape, buoyed by money but enjoyed by everyone. The High Line, too, he says, will be a public space that just happens to be surrounded by some of the most expensive real estate in the world. True—but unlike Central Park, the High Line isn’t big enough to allow you to ever truly escape that fact. Everyone, from park visitors to nearby diners to condo dwellers to hotel guests, will be invited to enjoy the High Line, but each from their own side of the glass.

As it happens, the High Line arrives at the exact moment when the legacy of Robert Moses—the imperious former New York City parks commissioner who had his own visions for the city—is being rehabilitated, or at least exhumed. Three separate museums this year mounted exhibits asking visitors to revisit his grandly imagined, and subsequently vilified, plans to remake New York into an expressway-laden megaplex, efficiently absorbing the daily swarms of auto-bound commuters. The most notorious of these schemes is the one that never got built: The Cross-Manhattan Expressway, an elevated highway that would have wiped out much of Soho and torn through the heart of Greenwich Village. Jane Jacobs, the feisty, elfin champion of small-scale urbanism, opposed, and eventually defeated, Moses, and her theories on lively neighborhoods with bustling sidewalks, with dry cleaners and diners and greengrocers, have been entrenched as conventional wisdom ever since.

Whatever you think of Moses’s legacy, there’s one thing Moses and the High Line have in common. We can look back now and see Moses’s work as an artifact of its time; a result, right or wrong, of his idea of the city, of what New York could, and should, become. The High Line, too—by which I mean the park, the neighborhood, the festival, the ballroom, the lounge—will one day look to us like a monument to the time we live in now. A time of great optimism for the city’s future. A time of essentially unfettered growth. A time when a rusted railbed could beget a park, and a park could beget a millionaire’s wonderland. And a time when the city was, for many, never safer, never more prosperous, and never more likely to evoke an unshakable suspicion: that more and more, New York has become like a gorgeous antique that someone bought, refurbished, and restored, then offered back to you at a price you couldn’t possibly afford.

The Life and Times of the High Line

1930s

Construction begins on the High Line elevated railway; trains deliver freight to local warehouses until 1980.

1980s

West Chelsea becomes notorious as a postindustrial wasteland, populated by body shops, truck yards, and transvestite prostitutes.

1984

Transportation consultant Peter Obletz buys the abandoned High Line for $10—allowing Conrail to avoid $5 million in demolition costs. The deal is later nullified.

1987

Dia Art Foundation moves to a warehouse in West Chelsea—and sparks an art-world migration that transforms the neighborhood.

1999

Chelsea residents Joshua David, left, and Robert Hammond meet at a community-board meeting and start Friends of the High Line.

2001

In his last days as mayor, Giuliani puts the demolition of the High Line in motion—but the plan is halted by a lawsuit brought by Friends of the High Line. (They lose the case but win the war—by converting Bloomberg to their cause.)

2001

After reading a story about the High Line in The New Yorker, Edward Norton contacts Friends of the High Line, and becomes a public face for the group.

2003

Friends of the High Line hold an open call for ideas; one of the winning entries is a 22-block-long swimming pool.

2006

Construction begins on the first phase of the High Line park—the railbed, pictured here in a Joel Sternfeld photo, is stripped to make way for a new landscape.

2007

The High Line Festival debuts on May 9, curated by David Bowie and featuring acts from Air to Ricky Gervais at venues as far-flung as Radio City Music Hall.

2008

The first phase of the High Line park is projected to open, stretching from Gansevoort to 20th. Meanwhile, the north leg of the High Line still faces possible demolition, pending the development of the Hudson Rail Yards.

SEE ALSO:

• The High Lining of New York

• The History of the High Line