Don Imus has a cockroach’s knack for survival. Over four decades on and off the air, the down-and-out uranium-mine worker turned multimillionaire thinking-man’s shock jock has made an art form out of bouncing back. He’s had drug problems, alcohol problems, health scares, and career crises, but somehow, Imus has always managed to step back from the brink. In 1977, for instance, he was famously fired from his job at WNBC radio for his dissipated ways and did a stint at Hazelden, only to resurface at a new station, more popular than ever. But this time, it seemed, he was cooked.

It was Thursday, April 12, and Imus had been slow-roasting for a week, ever since he called the young women of the Rutgers University basketball team a bunch of “nappy-headed hos.” Imus had insisted he’d meant it as a joke. But pretty much everyone else, from Al Sharpton down, took it as a bald-faced racial slur, made all the worse for having been directed at a group of plucky young women who had done nothing to provoke Imus but play their way into the NCAA women’s-basketball-tournament finals. The predictable media frenzy ensued, followed by Imus’s suspension from his WFAN-radio and MSNBC-TV gigs and his shaky self-justifications and mea culpas.

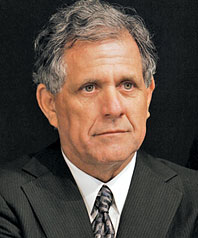

Now Les Moonves was set to fire the I-man, but he didn’t have his home-phone number. The polished, poised CBS president and the scraggly, cantankerous radio icon had never spent much time together. WFAN, which is owned by CBS, had made millions from Imus’s show during his twenty years on the program. And Imus had just signed a new five-year, $40 million deal with the network. But Moonves, a TV executive throughout his career, rarely ventured into the radio division. And Imus, whose signature cowboy hat and craggy face cast the original shock-jock mold back in the Transistor Age, had always operated in another universe, far away from the suits, playing by his own rules. The “hos” remark, of course, had changed all that.

Moonves had his assistant call WFAN to find Imus’s number, and Moonves reached Imus at his Central Park West penthouse at about 4:30 that afternoon. The conversation is said to have been brief and to the point. Minutes later, CBS issued a statement saying it was letting Imus go, with Moonves citing “the effect language like this has on our young people, particularly young women of color trying to make their way in this society.”

Imus wasn’t exactly surprised to get the call, but once it happened, he was shaken. He’d been counting on staying on the air at least for one more day. He was in the middle of his two-day radiothon to raise money for children’s charities, and the kids, in his mind, were depending on him. That night, he was going to meet personally with the Rutgers basketball team. After seeing them face-to-face, and asking for forgiveness, he thought perhaps he’d be able to turn things around. “Part of him said, ‘I can fix this,’ ” says Imus’s friend Bob Sherman. “You have to remember, he’s been a very powerful person. Mostly, he’s been able to control a lot about his life, even under some very self-imposed adverse conditions. The guy put himself in rehab and came back and went on the air—more than once. He thought an apology could take care of things.” But once he was actually let go, the enormity of all that had happened set in. “He felt less potent,” Sherman says. “He was amazed. It was shock and awe.”

A hermit even in the best of times, Imus mainly stayed home in the days after he was fired, playing chess with his 8-year-old son, Wyatt, and surfing the Internet. He planned to decamp to his ranch in New Mexico at the end of the month, the way he did every summer; everything else, he decided, could wait.

His close friends, meanwhile, kept wondering when Don would get mad. Privately, they say, Imus had taken a shot or two at Moonves. (“Imus knew Moonves was a weasel,” says one friend. The firing only proved it to him, the friend says.) But the chastened, repentant Imus that those close to him had seen emerge recently seemed like a stranger to them. When would he stop retreating and start fighting back?

Then, about a week after the firing, Imus called a friend on the phone, chuckling. The devilish rattle in his voice was back.

“Hey, I just hired the guy that defended Lenny Bruce,” he said. “Good luck, CBS!”

Don Imus, it turns out, isn’t cooked. Far from it. Hiring Lenny Bruce’s lawyer—the veteran First Amendment attorney Martin Garbus—was the first step in what appears to be an increasingly likely if improbable comeback. Officially, Imus is still laying low in New Mexico, overseeing his camp for kids with cancer and getting back to the land. But behind the scenes, Imus has been methodically engineering the resumption of his career.

Now, just four months after he spoke the fateful words that all but buried him, Imus is said to be on the verge of announcing that he will be back on the air, perhaps as soon as January. People with knowledge of Imus’s situation say he’s been approached by as many as three major media companies. There’s a chance that the Garbus lawsuit, among other factors, could even bring Imus back to his old broadcast studio at WFAN, working for his old boss, Moonves. So how did a man who said something deemed so awful by so many find a way to come back so quickly?

The floor of Martin Garbus’s office is covered with piles of hardcover books—most of them thick tomes of history, journalism, and law. There are a handful of titles by Garbus himself, whose first star client, Lenny Bruce, branded both men as noble defenders of free speech. But on the stack closest to his desk, toward the top, is something Garbus picked up and read only recently: God’s Other Son, a comic novel published in 1994 by Don Imus.

Imus met Garbus for the first time when he walked into the lawyer’s office in late April. “He seemed very, very bright,” Garbus says. “Happy, satisfied with his life, good marriage, respects his wife. He’s very funny.” (According to one friend of Imus’s, it was Imus who approached Garbus.) Days later, Garbus went on a media tour announcing he was planning to file a $120 million wrongful-termination lawsuit on behalf of Imus against CBS.

Garbus announced that Imus’s contract not only allowed the shock jock to be risqué but demanded it, that his bosses at WFAN and CBS Radio were required to warn him at least once about his behavior before firing him, and that nothing Imus said on the air—not the hos quote or anything else—even came close to violating the standards of legal speech set by the FCC. The draft of the $120 million lawsuit demands that CBS honor Imus’s contract and pay him the $40 million owed to him under his brand-new five-year deal. The other $80 million in the proposed lawsuit is to pay for lost income for the charities Imus endorsed on the program.

Even without actually filing the suit (a step he still hasn’t taken), Garbus scored several points. First, he repositioned Imus as a victim, not a villain (Imus wasn’t the bad guy here; the suits who fired him without cause were). He also staked out the legal high ground in the CBS contract dispute, should the matter ever come before a court. The nappy-headed-hos comment, Garbus says, was clearly a joke, not a slur, and in no way falls into the category of prohibited speech. Firing Imus for the remark, he argues, didn’t just violate the terms of his contract—it was unconstitutional. Essentially, Garbus is deploying the Lenny Bruce defense. “Bruce had a joke where a couple of guys are sitting around playing poker,” Garbus remembers. “One guy said, ‘What do you have?’ and the other says, ‘I got two kikes, a wop, and a chink,’ and the other guy says, ‘Oh, I have three niggers, a dago, and a so-and-so.’ And he kept throwing out the words. He said, ‘If I use it in this context, you understand it’s a joke.’ He said that words don’t have any meaning. It’s the meanings that you impart to them.”

And what was the meaning of Imus’s comments? Before he was fired, Garbus says, Imus was saying ho on the air a lot, actually; not just about the Rutgers women but about his wife, Deirdre, a committed environmentalist he dubbed “the Green Ho.” It was like Lenny saying nigger, Garbus argues, because he was making it clear that there are people out there who use that word all the time, unironically—in Lenny’s case white racists, and in Imus’s case the hip-hop crowd. According to Garbus, when Imus said “nappy-headed hos,” he was being ironic—goofing on the pleasure white society gets from co-opting the lexicon of the black world. It’s a highbrow variation of how Imus’s producer-sidekick, Bernie McGuirk, who said hos right before Imus did on the air that April morning, explained the whole thing on Hannity & Colmes: “You know, we’re trying to be—or I was trying to be—cool.”

That argument, of course, doesn’t wash with everyone. In our discussion, Garbus brings up the book Nigger, by Randall Kennedy, the Harvard law professor, that explicates the different connotations of the word, depending on the context. He calls it a wonderful book. Unfortunately for Garbus, during the Imus controversy in April, Kennedy told Reuters that he found Imus’s comments “terrible and reprehensible … ‘Nappy-headed’ could be used in a variety of ways, it can be said lovingly or in a complimentary way, but Don Imus said it to express casual contempt.”

Garbus clearly doesn’t see it that way. “Nappy-headed hos is not nigger,” he says. “As I said, it depends on the context in which you say it. And that was Bruce’s point: It depends on how you say it and when you say it.”

And that’s your point in this lawsuit, I ask—context is everything?

“Context is a great deal of it,” he says. “I don’t know if it’s everything.”

Les Moonves is known to be highly committed to the success of CBS and equally concerned about his own image. Moonves fired Imus, his critics say, not out of any sense of social justice but only after it became clear that Imus was becoming a liability to the network and a personal embarrassment to Moonves (Moonves’s detractors note that he only cut Imus loose after seeing his rival Jeff Zucker, the president of NBC Universal, release Imus from his MSNBC simulcast). Firing Imus was supposed to be an unqualified win for Moonves and the network. Yes, there would be a short-term revenue hit, but top advertisers were already dropping out, and others were threatening to follow suit. By firing Imus, Moonves could prevent further damage to the network and come out looking like a man of principle.

Only it hasn’t quite worked out that way. After Imus was fired, the ground under Moonves began shifting. WFAN started losing money. A lot of it. “Imus used to sell spots for $1,500 that are now going for, like, $200,” one source says. While in the months before Imus’s firing his ratings weren’t where they used to be, the elite demographics of his audience meant he was still printing money for his bosses. “He was like a golf tournament toward the end,” says John Mainelli, a radio-industry consultant who until recently was the program director for a CBS-owned radio station. “He didn’t have big numbers, but he had so-called ‘quality’ numbers, politicians and high-income people.”

The station tried replacements for months, but none seemed to work. There were conspiracy theories that some of the folks at WFAN who had always disagreed with the decision to can Imus weren’t trying very hard to replace him. Fill-ins like Geraldo Rivera and John McEnroe didn’t generate much by way of excitement or ratings. In July, WFAN celebrated the station’s twentieth anniversary by running a “Best of Imus” clip show, during which Mike Francesa, the popular co-host of “Mike and the Mad Dog,” thanked Imus and said twice that he hoped that, come September, they will “be a complete team” again. In a Daily News online poll conducted in late June, 94 percent of respondents supported Imus’s reinstatement.

Perhaps more than anything, it was the lawsuit that changed things. No one at CBS will confirm it had an effect, but after it was filed, network executives began considering the unthinkable: bringing Imus back. Giving Imus his old job wouldn’t just help restore WFAN’s morning ratings—it would quite possibly cost less than having to go to court with Imus. What if, instead of fighting, CBS renegotiated to take Imus back at, say, half the $40 million? Or even a third? “They desperately need the revenue,” says Mainelli. “This is no secret. Les Moonves has said he loves the cash flow that radio provides, but it’s no secret he thinks there ought to be a lot more of it.”

What about the protesters? Wouldn’t the same tsunami of anti-Imus forces regather? Wouldn’t the advertisers boycott? Perhaps. But then Al Sharpton started telling reporters that he, at least, wasn’t necessarily against the idea of Imus’s coming back on the air. “The demand was he be fired from a job he routinely abused,” Sharpton told me in July. “There was never a sense that he be removed from making a living.” Where Sharpton goes, advertisers might follow: The door, it seemed, was cracked open.

Imus, his friends say, is burning to get back on the air. He wants to be a part of the conversation again, especially now. “He’d like to be around for the presidential race,” says Bob Sherman. He also feels pressure to sustain his charity work and to support Deirdre, who has benefited from Imus’s radio plugs for her line of ecoproducts and her own charitable causes. What a comeback is really all about for Imus, though, is not letting “nappy-headed hos” be his career epitaph. “He certainly doesn’t want to end on that note,” says a friend.

Over the summer, sources say, CBS and Imus began talking about a possible comeback (though neither side will confirm nor deny any such talks). At one point, sources say, CBS had also started negotiating with Boomer Esiason, another temporary Imus fill-in, to take Imus’s slot at WFAN. But as the weeks went on and no deal was announced, rumors began to circulate that CBS wanted to wait and see if the climate changed, making an Imus return more feasible. Imus’s friends, meanwhile, began whispering to Matt Drudge and “Page Six” that an Imus return was imminent. The gossip game got more interesting when rumors surfaced that Imus might instead sign on at another station.

Where else might Imus go? Satellite isn’t attractive to Imus the way it was to Howard Stern, according to one close friend. The money might be good, but “it would be a small audience, which would have an effect on his guests, and on his charitable work.” And both XM and Sirius (currently in merger talks) have budget issues. Sirius CEO Mel Karmazin loves him, “but Mel’s not going to hire him,” says a source. “There’s not much money to go around after Howard Stern.”

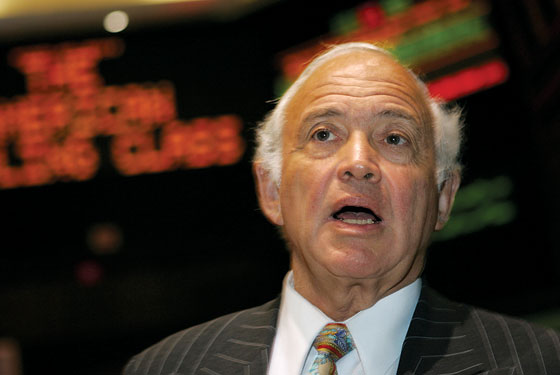

The three traditional radio companies, Citadel, Clear Channel, and Buckley Broadcasting, meanwhile, have all put out feelers. Citadel appears to be the most serious suitor of the three. It just bought WABC and the ABC radio network nationwide. Citadel is run by Farid Suleman, who was Karmazin’s No. 2 for many years at Infinity when Imus was a star there, and Suleman was the comptroller then. So he understands the money Imus generates. WABC in New York already has a successful morning team in Curtis Sliwa and Ron Kuby (and Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity later in the day). But one knowledgeable source says that putting Imus in that morning slot could increase the company’s revenue by as much as $20 million. “I think if Don was available, we would be very happy to see what we could do,” Suleman says. He sounds like he’s already got his answer to the inevitable “How can you justify this?” question already written. “What he did was wrong. But the consequences of what he did seemed out of proportion.”

Another possibility would be for Imus to strike out on his own—to create a syndicated program and sell it town to town, door to door. “He’d be working for himself,” one Imus friend says. “He’d own all his rights. That’s how Rush Limbaugh started.” Then there’s TV. There’s no reason why Roger Ailes wouldn’t want to talk with Imus—and one friend of Imus’s says he has heard as much (a Fox spokeswoman says she has no knowledge of such a conversation and that the network is not currently in talks with Imus).

In the end, several sources say, Imus will most likely reach a settlement with CBS and go elsewhere. A source close to Imus says Esiason, despite CBS’s flirtations with an Imus comeback, is almost a lock as Imus’s replacement on WFAN. “They’re going to announce Boomer soon,” he says. “But they also have to have an Imus settlement done in time. Because legally, if they hire someone while he’s still under contract, it worsens their position if they’re in a lawsuit.”

According to one knowledgeable source, the settlement deal on the table at the moment has the money worked out—not the $40 million Imus signed for but not nothing, either. There also may be a limited noncompete feature, requiring Imus to agree not to go anywhere else until January. The potential settlement is also said to include a non-disparagement agreement. “He won’t be able to say anything about Les or CBS for a number of years,” a source says. That clause, the source says, means as much as anything to Moonves.

There’s always the possibility, of course, that no one will hire Imus. For a new employer, taking him on would mean building an expensive new franchise around a 66-year-old shock jock who said something that many people still find unconscionable. “Someone’s going to have make an investment in him until he’s 71,” says one friend. “They have to believe that he’ll still be getting listeners six months after he comes back.”

Most of his friends, however, are certain Imus will be back. The only questions are where and when. “Willie Nelson told me that his favorite thing in his life since he was a little kid was to get into trouble and then get out of it,” says Kinky Friedman, the songwriter, columnist, and recent Texas gubernatorial candidate who is one of Imus’s best friends. “And I think the same thing can be said of Imus. The time he was fired from New York and sent down to Cleveland, for cocaine and alcohol and everything, I never thought I would see him alive again. When I said good-bye to him, I thought, ‘That is it. He will never come back.’ And he rose like a phoenix.”

If he does come back, will he return a changed man? “I don’t think he’ll give up his sense of humor,” says Michael Lynne, the New Line Cinema president who has been Imus’s friend for 35 years. “But I do think he’ll be more sensitive to the implications of words that are said on the air and whether they’re hurtful or not. Don has something meaningful to contribute in terms of creating a dialogue in our society—not just about politics or books but about race and diversity. I think he can be a force for good in that dialogue when he comes back.”

Imus has been cagey on the phone with Friedman lately, but nevertheless clear about what he wants to happen next. “He’s got a secret plan he mentioned, but he won’t tell me what it is. Of course, you don’t want to tell me anything, because I’m the town crier. He’ll be back. It’s his M.O., you know?”

In any case, he hopes so. “I call him a truth-seeking missile,” Friedman says. “He is totally ruthless about it. And, you know, we need this. Society needs someone like this. In that sense, he’s a lot like Lenny Bruce.”

Or perhaps, inevitably, he’s just Don Imus. “Here’s what you have to remember about him,” one friend says. “I love him, but he’s a really angry guy. A recovering alcoholic, okay? So he has demons sometimes.” That, his friend says, “can be difficult.”