This is deeply weird. For hundreds of miles, the central-Florida interstate has been lined with trailer parks and parched ranch lands. Switching to the two lanes of Highway 301 sends me along the broken-down main street of a town called Oxford, which is lined with single-story, mostly vacant redbrick houses, barbecue joints, and auto-repair shops, a reminder of the days when Florida was actually a part of the Deep South. Then, a right turn and authentic redneck suddenly gives way to invented oasis: 33 lush, manicured golf courses. Pods of new half-million-dollar houses, clustered behind security gates. Man-made lakes and streams gently burbling. This is the Villages, a 26,000-acre, three-county development with 68,000 residents, sprawling its way to a population of 100,000 in the next ten years. Calling the Villages a retirement community demeans the genius of the concept. This is nothing like the slabs-of-concrete condo towers and shuffleboard courts off I-95 around Fort Lauderdale or Miami where thousands of New Yorkers, like my grandparents, fled the Northeast winters after turning 65. The Villages is a dreamland for the active, well-off elderly, created by a Florida real-estate magnate who is also a powerful Republican fund-raiser.

The Villages’ “town square” is a brilliant piece of nostalgia, an idealized small-town midwestern crossroads circa 1954. There’s an old-timey movie house, prefaded copper roofing on the expensive boutiques, and fake historical markers on buildings like “Skip’s General Store.” Thousands of residents are strolling toward the central weathered-wood bandstand waving small American flags. Yet just when the atmosphere starts to seem oppressively cloying, I notice that many of the old folks gabbing beneath the palm trees are good and drunk. It’s the daily happy hour, and the open-air bars lining one side of the square are jam-packed. The Villages is Celebration crossed with Geezer Spring Break.

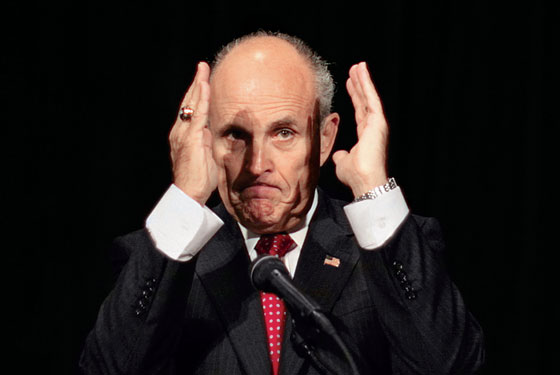

Now the wholesome, pleasantly toasted crowd is roaring: America’s Mayor has just climbed onstage. Rudy Giuliani peels off his navy suit jacket and rolls up his shirtsleeves, grinning so wide that every one of his suspiciously white teeth is visible. Six years of nearly nonstop speechifying, selling either his own book or George W. Bush, have made Giuliani a masterful campaigner. He still has that odd lisp, and his accent is irreducibly New York, so that the name of today’s state comes out “Florider.” But Giuliani is relaxed, confident, able to quickly incorporate whatever the moment may offer to the narrative of his own greatness. “I see a New York Yankee hat!” he says, to cheers. “And I see a Brooklyn Dodger hat! So I’m gonna tell you why I’m such a determined person and I fight so hard for what I believe in. You know why? Because I was born in Brooklyn. But I was born about one mile from Ebbets Field—and I was a Yankee fan. I was a Yankee fan in Brooklyn!” Laughter, applause. “My father … put me in a pin-striped uniform and sent me out to play with all the other kids in Brooklyn. Oh-ho! So I had to fight my way just to get to the candy store.”

The next 45 minutes wander from gushy Ronald Reagan tributes to complicated plans for a 2,000-mile immigrant-repelling border fence to a discourse on the infallibility of the Founding Fathers. Central to it all, though, is Rudy the resolute, the lonely man tough enough to stick selflessly by his convictions, even when they’re unpopular, until he’s ultimately proved right. And the proof is his glorious success as mayor of the most dangerous, most corrupt, most Democratic city in the land. “Every candidate promises you lots of things,” he says. “The most important thing is, can somebody deliver? Can they get something done? Well, here’s what I have to offer: I know how to get things done. I did it in the place where it was really hard to do! Nobody, nobody really got anything done in New York about crime, about welfare, about the condition of the streets, about our economy, about bringing jobs to New York! Not only did nobody get anything done for a long time, most people had given up, and they didn’t think anything could be done!”

This is a disorienting notion—but the condescending attitude is completely familiar to any New Yorker. The city in the nineties was far from perfect. But were we really living in the hellhole of depravity and despair that Giuliani describes without ever realizing it? And was he the man who single-handedly tamed 8 million misbehaving New Yorkers, delivering us from an economic and physical nightmare? They sure think so out here in the real America: The chants of “Roo-dee! Roo-dee!” are drowning out Giuliani’s final words, and women are elbowing one another in pursuit of his autograph.

It’s the crucial second plank of his presidential platform, fitting snugly between the invocation of his September 11 heroism and his mocking of Hillary Clinton: Rudy Giuliani is the man who saved New York. His campaign TV ads are a perfect distillation of the strategy. Before Mayor Rudy, the city was a black-and-white jungle-land of sex shops, violence, and crushing taxes. After Rudy, New York is Oz: sunshine, happy young couples, and shiny gold-plated statues. The message, which Giuliani hammers in his appearances outside the city, is that he made big bad New York safe for the rest of the country. For the pitch to work, Giuliani has to demonize the city he inherited and claim all the credit for the improvements he left behind. The city itself is his original enemy.

The brilliance of this story line (for a formerly very liberal Republican) is that it is based more on “character” than on any specific policies. Giuliani is running for president not on what he stands for but on who he is: the one man tough enough to subdue New York.

Of course, Giuliani’s character is what the city knows best. New York knows Giuliani is capable of quiet grace—and of cheap cruelty. He shook the city’s political culture out of its lazy, reflexively liberal posture. But Giuliani’s personal character is defined by a parochial, boys-from-the-neighborhood attitude that’s far more old-school bossism than 21st-century globalism. That bunker mentality was useful when Giuliani was enduring the withering criticism that came with overhauling the city’s welfare bureaucracy. But it also underlies the ugly racial polarization Giuliani stoked. And his character includes the cronyism that created the Bernie Kerik debacle.

In the current production, the part of David Dinkins is played by Hillary Clinton, rampant crime is played by Al Qaeda, and welfare cheats have been replaced by illegal aliens.

So far on the campaign trail, the genial Rudy has been showing his face. The city saw plenty of that other guy—the nasty, credit-hogging, conflict-addicted, wife-humiliating Rudy. The man who tried to put himself above the law and stay mayor after September 11. And we know he’s still in there.

Lately, as he’s fallen behind Mitt Romney in early Republican-primary states, there have been flickers of the autocratic Rudy. That’s why the most important lines in Giuliani’s TV spots and speeches aren’t the ones about crime or welfare, but those about being tested in a crisis. Giuliani wants that phrase to be code for 9/11. And indeed, at the beginning and end of his years as mayor, when the city faced physical peril, Giuliani rose to the occasion. But New York, from all the years in between, knows something else about his character that maybe the rest of the country should notice: If a crisis doesn’t present itself, Rudy Giuliani can be counted on to create one.

Even as Giuliani runs away from New York, one fundamental thing remains the same as it was when he was shaking hands at subway stations in 1993: He’s running a campaign rooted in fear. In the current production, the part of David Dinkins is played by Hillary Clinton, rampant crime is played by Al Qaeda, and welfare cheats have been replaced by illegal aliens. The star of the show is still Rudy, the strongman who can protect the vulnerable, right-thinking citizenry. He’s promising to do for the country what he did for the city.

Yet with the benefit of hindsight—and especially with the ongoing contrast to Michael Bloomberg’s lower-volume years as mayor—it’s possible to see much more clearly the places Giuliani deserves credit for helping to save New York. It’s now equally clear where the story he tells is more myth than reality.

You could hear the man thinking. In 1989, Rudy Giuliani was a famous prosecutor making the transition to political candidate. He sat for an interview with New York’s then–political columnist, Joe Klein, that was fascinating because of Giuliani’s willingness to think out loud and in print. Giuliani openly, humbly admitted to all the things he didn’t know.

Nice didn’t work for Giuliani. He lost that election, but he learned his lesson. The next time around, in 1993, he came out punching and never stopped. Not only was it a winning electoral strategy, but the pugnacity was a perfect fit for that moment in the life of the city. The crime tide had already started to shift, yet New York was still suffering from a widespread reputation for anarchy on the streets and lassitude in city government. Giuliani rammed, head first, into the entrenched interests. His pugilism produced great headlines, and spectacular results: Crime plunged, the homeless were made to disappear, and the city once again had someone emphatically in charge. Attacking—all the time, relentlessly—worked.

Taking control, however, was never enough for Giuliani. When a newspaper story gave passing mention to David Dinkins’s role in bringing Disney to Times Square, Giuliani raged in a press conference that he deserved the credit. But that skirmish was nothing compared to Giuliani’s war with the man who laid the foundation for New York’s revival and for Giuliani’s mayoral triumphs.

Bill Bratton came to New York from Boston in 1990, hired by the MTA to overhaul the city’s transit police. Four years later, the new mayor appointed Bratton police chief. The efficiency and aggressiveness of the NYPD increased markedly under the new leadership. And the department’s combination of street-savvy personalities and nuevo-thinking made for an irresistible, media-ready narrative. The murder rate dropped 74 percent. But murders also dropped 73 percent in San Diego; killings were down 70 percent in Austin, 59 percent in Honolulu, and 56 percent in Boston. None of those miracles, however, was accompanied by a cult of personality forming around the relevant mayor.

There’s now a large body of research indicating that crime would have shriveled even if New York hadn’t been lead by two self-proclaimed geniuses. The crack plague burned out just as Giuliani and Bratton deployed an additional 8,000 men and women in blue—thanks to President Bill Clinton and David Dinkins, Giuliani’s much-derided predecessor at City Hall. The murder rate had actually begun declining in 1991, under Police Commissioner Lee Brown, and continued to fall under his successor, Ray Kelly; Dinkins, however, wasn’t quick enough or deft enough to claim credit. Giuliani and Bratton took full advantage of the increase in manpower and were even better at exploiting the media attention.

Bratton was too good at it, at least in his boss’s view. Giuliani couldn’t stand Bratton sharing the spotlight and forced him out of the job months after the chief’s appearance on the cover of Time. Under Bloomberg and the reinstalled Kelly, crime has continued to shrink—even as crime rates have rebounded in other major cities and even though the current department is working with less money and fewer cops.

For his campaign to work, Giuliani has to demonize New York and claim all the credit for the improvements he left behind.

But the constant confrontations and Giuliani’s growing ego did more than drive away top talent from his administration. As the end of his time at City Hall grew near, he’d also lost nearly all his intellectual curiosity as well as his sense of humor. Or maybe he’d simply run out of worthy villains.

The senior citizens boo on cue when Giuliani uses the words Hillary Clinton and higher taxes in the same sentence. “The best thing to do, and I did this in New York, is to reduce the size of government and to reduce the amount of taxes that we charge you,” Giuliani says, to sustained applause. “People said it could not be done in New York. When I proposed doing it, they laughed at me! When I proposed doing it, the New York Times wrote editorials explaining how irresponsible it was.”

From the back, there’s a shout, loud and clear: “The New York Times sucks!”

After he stops laughing, Giuliani playfully pretends to take offense. “Now, now—we don’t talk that way! We don’t say bad words! We’re the party of family values! The way we say it is, ‘The New York Times is incorrect.’ And they are! I lowered taxes in New York 23 times! Nobody had ever done it more than once. I did it 23 times! Nine billion dollars!”

Now it’s Giuliani’s turn to be incorrect. The city payroll ballooned by 25,000 during his tenure. Eight of those 23 tax reductions came from Albany. A ninth, by far the largest, originated in the City Council—and Giuliani fought it, tooth and nail, for nearly two years. The truly rich irony in that episode, the expiration of a 12.5 percent surcharge on personal income, is that it’s the same tax Dinkins, with the help of Council Speaker Peter Vallone, added to hire more cops. Some of Giuliani’s tax reductions seem purely symbolic, like slashing the levy on “coin-operated amusement devices.”

Even conservative economists were disappointed by the gap between Giuliani’s rhetoric and results. “By big-city standards, he has a reasonably conservative fiscal record—that he has inflated,” says E. J. McMahon of the Manhattan Institute. “The tax cuts enacted during Rudy’s tenure did, indeed, contribute to the city’s economic growth. But he funded the biggest increase in school spending that had ever been seen up to that point. He talks now about collecting more revenue with lower taxes—of course he did! The economy was booming!” When a recession started, Giuliani wasn’t able to adjust. His borrowing and spending helped transform the city’s $3 billion budget surplus into a $4.5 billion deficit—most of which piled up prior to September 11.

Giuliani’s other signature accomplishment is his slashing of New York’s welfare rolls. By making the city’s welfare-application procedures more rigorous, by requiring work in exchange for a check, and by combing for fraud, he trimmed the welfare rolls by 500,000 people. “Giuliani’s achievement was considerable, in some ways more impressive than what happened in other big cities, because the culture here is very averse to the assumptions of welfare reform—individual responsibility, a rejection of claims of disadvantage by people who are poor,” says Lawrence Mead, an NYU professor who is one of the intellectual fathers of “workfare.” “The ethos of the community groups was totally rejected by Giuliani. He did it without apology and without compromise. He didn’t even maintain appearances.”

But the rest of the story illustrates the sleight of hand Giuliani uses to embellish his record. “His welfare people matched the city data with the State Department of Labor data, and basically found that people were working already,” says Ester Fuchs, a Columbia University professor of public affairs whom Bloomberg hired to evaluate city government when he was elected. “So they found fraud, sent out letters, people left the rolls—and they were instantly employed!” Weeding out fraud is an inarguable achievement, but Giuliani makes it sound as if he also created a robust jobs program.

Locking up criminals and clamping down on welfare cheats played to Giuliani’s talents as a prosecutor. Issues that required patience and diplomacy, like fixing the public-school system, frustrated him to fury. Other agencies that Giuliani did control simply didn’t function by the time he was done with them.

“One of the most amusing things about Rudy is his crisscrossing the country speaking on ‘management,’ ” Fuchs says. “City Hall didn’t even have functional e-mail when we arrived—in 2002! You cringed when you looked at the capacity of agencies to really do what they were supposed to do.” Giuliani’s supporters trumpet his personal incorruptibility, but as mayor he larded his administrations with unqualified cousins and cousins-in-law.

Though the current building boom has been fueled by the surging national economy, City Planning Director Amanda Burden and Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff have been creative in finding ways to advance the cause—to the point at which many neighborhoods are cringing beneath the glut of high-rise construction. “The cupboard was totally bare [when we took over],” a Bloomberg economic-development official says. “The Giuliani administration’s view was that you improve the quality of life and economic development will occur. Up to a point, that view is correct. But we had to start from scratch on literally hundreds of different projects.” Bloomberg’s impact on city life—from 311 to the smoking ban to public schools and massive infrastructure projects—is likely to be farther-reaching and longer-lasting than Giuliani’s. And Bloomberg still has two years left in office.

Some of the forces responsible for the city’s rebound are largely outside the influence of mayors. “What has really enabled New York to be so resilient in the face of all these challenges—white flight, disinvestment, de-industrialization, global competition, 9/11?” asks John Mollenkopf, a CUNY professor of political science. “New York is trying to sail upwind against some fairly strong storms. Yet the population is going up, per capita income is going up in real terms. How did we do it? It’s kind of crass, but New York has continued to be a place where a lot of people can make a lot of money, which attracts one kind of talent. The corollary to that has been immigration. The city has been renewed by the continuing influx of diverse, energetic newcomers. It’s sad to see Giuliani turn from what he said on immigration as mayor, when he was very welcoming, because he senses the anti-immigrant winds blowing through the Republican Party.”

Sad, maybe, but not out of character. “It’s insulting to every New Yorker that he goes around the country talking as if he thinks he was the animal tamer and we were the animals,” Ed Koch says.

Especially when it was Giuliani who so often riled up the animals in the first place.

Giuliani arrived at City Hall at a pivotal moment in New York’s history, and his contribution to the city’s revival was enormous. Yet his true legacy is more attitudinal than programmatic. At a time when the city’s spirit and public image were taking a beating, he made an invaluably emphatic statement that New York was worth fighting for. The downside to Giuliani’s temperament was that when battles didn’t present themselves, he invented them or lost interest. So with murder rates plunging, Giuliani turned his sights on jaywalkers, hot-dog vendors, and sensation-seeking artists.

“In the second term as mayor, I think he got depressed,” Fran Reiter says. “The minute he won reelection, he realized it was the beginning of the end. With the exception of welfare reform, he stopped focusing on the big stuff.” Instead, Giuliani dwelled on the petty, even when it meant turning his back on loyal friends. One of them was Reiter, a Liberal Party veteran who served as a deputy mayor in Giuliani’s first term and managed his second winning campaign. Reiter then found herself on the outside of Giuliani’s shrinking inner circle, for reasons she says are still mysterious. She’s now backing Clinton. “Whatever issues I have with him, I believe Rudy saved New York,” Reiter says. “But I’m not convinced the things he did as mayor, and the way he did them, will translate well into the presidency. I know a lot of good people he pushed away. There’s a tendency for Rudy to personalize stuff and be unforgiving of differences of opinion.”

The litany of needless fights Giuliani picked as mayor is astoundingly long. Some of the confrontations at least had their origins in policy differences or political calculation. That category includes his battles with the Port Authority, over control of development projects, and with the Brooklyn Museum, which Giuliani smacked around in order to boost his conservative credentials for a prospective Senate race.

But even if a dispute had started over issues, Giuliani would escalate it into a playground contest of insults. His feud with George Pataki started with Giuliani’s saying “ethics will be trashed” if Pataki was elected governor, and it never really ended, descending at one point into a standoff over who should call and apologize first. Giuliani assailed Schools Chancellor Ramon Cortines as “precious” and a “little victim.” Sometimes Giuliani simply froze people out without provocation; for years, he refused to meet with mild-mannered Manhattan borough president C. Virginia Fields, who happens to be black. Other times, his anger just seemed disproportionate, as when Giuliani blasted the head of the Grammy Awards. Often, though, his tantrums were gratuitous: calling a Bronx schoolteacher a “jerk” when she dared to question his commitment to better schools, for instance.

Easily the lowest moment, however, came in March 2000. Three weeks after a jury had acquitted the police officers who shot Amadou Diallo, when emotions were still raw, Patrick Dorismond was killed by an undercover cop after saying no to drugs. Giuliani trashed the victim, releasing Dorismond’s sealed juvenile records and sneering—wrongly—that the dead man had been “no altar boy.”

“Rudy’s not a racist, but he loves to inflame,” says Ed Koch, a connoisseur of conflagration. “He loves to spit in your eye. It’s character, not strategy. He’s acted reasonably polite since September 11, and he can be very charming. But unless you’re a saint, an epiphany does not make a permanent change in you. And he’s no saint.”

Any discussion of Giuliani’s character inevitably leads back to two issues: his family and his friends. The significance of last week’s story on Politico.com about Giuliani’s jaunts to the Hamptons wasn’t the exposure of an accounting shell game; it was the reminder of the casual arrogance and viciousness that permeated Giuliani’s mayoralty. He ran up the public tab while pursuing an extramarital affair. The fact that Giuliani has been married three times may give pause to voters elsewhere. The city wasn’t so much troubled by the divorces themselves. What’s indelible and unforgivable to New Yorkers is the grotesquerie of Giuliani’s press conference dropping the news on Donna Hanover and a live television audience. The ugliness of that moment lingers, to many a distillation of his core ruthlessness.

The other key marker of Giuliani’s character is his New York inner circle—and its most infamous member, Bernie Kerik. The two met at a New Jersey fund-raiser in memory of Michael Buczek, a 24-year-old city cop. Buczek was shot and killed in Washington Heights just blocks from where Giuliani, with his then-friend Senator Al D’Amato, had staged an infamous buy-and-bust photo op at the height of the city’s crack epidemic. When Giuliani ran for mayor in 1993, Kerik got himself assigned to the candidate’s protective detail. Giuliani quickly promoted his friend from obscurity, first to deputy commissioner of the Correction Department, then two years later to boss of the city’s jails. These days, Giuliani defends Kerik by pointing to the reduction in violence at Rikers Island under his friend’s watch. While that’s true, Kerik ruled with an iron hand, racking up enemies and ethical messes, among them dating one of his female subordinates. When he married another woman, Kerik was accused of assigning corrections officers to staff the wedding.

Giuliani and Kerik grew ever closer, with the mayor serving as godfather to two of Kerik’s children. In 2000, Giuliani elevated Kerik to police commissioner. “Too many leaders overlook candidates with unusual résumés because of a failure of nerve,” Giuliani wrote in his 2002 book, Leadership. A willingness to hire people with interesting lives is admirable, and it’s a trait too often lacking in an American political culture scared of Drudge and Fox. But Giuliani goes further, enlarging his tolerance into an unshakeable faith in the genius of his own judgment. “By the time I appointed Bernie Kerik, I had hired so many people that I was immune to such criticisms … I believe that the skill I developed better than any other was surrounding myself with great people.” And once he’d become deeply invested in Kerik’s success, Giuliani ignored any facts that might contradict his perspicacity, as when the city investigations commissioner mentioned Kerik’s connections to a contractor with alleged mob ties.

There were plenty of dubious episodes on Kerik’s public record, including his order for 30 miniature commemorative busts of himself as commissioner. And we now know that Kerik’s sixteen months as police commissioner were busy with much more than crime-fighting: apartment renovations paid for by a contracting firm that was trying to win city business, the use of city detectives to do research for Kerik’s autobiography, and an affair with the publisher of that book, Judith Regan. Yet Giuliani stayed loyal to Kerik, and has only recently, and mildly, distanced himself from the disgraced commissioner. But there are some things from his New York past that Giuliani can’t shed. The relationship, still only partly understood, is an especially important marker in understanding Giuliani’s character. Maybe standing by Kerik so long is simply part of his code of loyalty. Leave it to Kerik, now under federal indictment, to give that bargain an especially sinister edge: In his Regan-edited book, Kerik wrote that he felt like a made man in Rudy’s mafia.

Gosh, there are more Republicans on this side of the room than there are in all of New York City,” Giuliani said at a campaign stop in South Carolina. “So I am really comfortable here.” In the reddest states, he uses the city as his foil. “I got elected and reelected honestly not because the people of New York City agreed with my ideas,” he says Down South. “They didn’t. They agreed with my results. You agree with my ideas.”

He’s painting himself as a citizen of picket-fence America. Long gone is David Garth, the prototypical New York adman who steered Giuliani’s first victorious mayoral campaign. Now Giuliani’s image is spun by consultants with vast experience in states that are very much not New York. The leader of his creative team is Heath Thompson, a Dallas-based consultant whose most famous TV ad ran in last year’s Senate race in Tennessee: The come-hither blonde whispering breathy invitations to black Democratic candidate Harold Ford. Scott Howell, another important media operative, has won U.S. Senate races in Texas, Georgia, and Missouri and learned his trade from Lee Atwater.

They’re trying to pull off the nifty trick of packaging Giuliani, the Yankees mascot, as being from New York but not of New York. Giuliani did indeed arrive at City Hall as a refreshing outsider to the city’s dominant political culture—he was a Republican in an overwhelmingly Democratic town, a prosecutor not a career politician, an outer-borough Roman Catholic in a Manhattan-centric, agnostic world. But that doesn’t mean he’s not a New Yorker. In fact, many of his character traits—his anger, his blind loyalty—come straight out of the tribal culture of New York’s old neighborhoods. On the presidential-campaign trail, Giuliani defines every issue and problem facing the country—not to mention his political competitors—as “enemies.” He sees an America besieged—by illegal aliens, by liberals, but most of all by Islamic terrorists. “We are the strongest country on earth, but we need a very, very strong military to protect us and to defend us,” he says in Florida. “And if I’m elected president of the United States, I will rebuild our military! I will make up for the damage that Bill Clinton did to our military!” Never mind what George Bush has done to our military.

Just then, there’s a murmur in the crowd. People are pointing at the sky behind the stage. An eagle is hovering against a backdrop of ominous gray clouds. “Oh, look at that!” Giuliani says. “I think he liked that message about a strong military!”

When the applause fades, he picks up where he left off. “We also have to be concerned about some specifics, like what do we do about Iran.”

“Nuke ’em!” comes a shout.

Giuliani grins. “If I’m president of the United States, it will be crystal clear we will not allow Iran to become a nuclear power. We will take whatever action is necessary to stop them! We will not take the military option off the table. We will not beg to negotiate with them. We’re gonna make them beg to negotiate with us!”

Giuliani says he wants to do for the country what he did for the city. Yet the tactics he used in New York are either inapplicable or irrelevant. Crime is down nationally, and Bill Clinton reformed federal welfare policy; lowering taxes seems extremely unlikely, especially if a recession sets in. What would certainly be transferred to the White House, though, is Giuliani’s character. He’s selling his strength of will as an indispensable trait in a tough world. But we know from eight years of firsthand experience that Giuliani’s strength would also mean degrading his enemies, a contempt for the press and Congress, a mania for secrecy, and the rewarding of personal loyalty at the expense of competence.

And instead of the NYPD, he’d be expressing his strength through the U.S. military. In the sultry Florida air, in the center of a retirement fantasia, Giuliani is suggesting he’d clean up Islamic terrorists like so many South Bronx crack dealers. He’s repeating one of his favorite phrases, that a President Giuliani would “keep us on offense” against terrorism. But it’s the way he says it that rings suddenly loud and clear. This was the man who told President Bush he wanted to personally push the button to execute Osama bin Laden. Anyone who was downtown on September 11, 2001, can empathize. But Giuliani has internalized one side of his hometown too deeply: the side that doesn’t just fight back but isn’t happy unless it’s in the middle of a brawl.

Giuliani’s well-worn anecdote about his boyhood bond with the Yankees is meant to show his determination in the face of pressure. But New Yorkers know there’s a less flattering interpretation. For most of Giuliani’s life, the Yankees have been the richest, most powerful, and usually winningest team in baseball. Yet the ultimate fan of baseball’s biggest overdog thinks he’s a brave, oppressed partisan of an underdog. Giuliani won back the city from the mongrel hordes—the descendants of Brooklyn Dodgers fans—and now he’s proposing to win back the world for America. But New York, more than anyplace, is wise to Rudy Giuliani’s game.