Things were looking good. My doctor had gone through the test results and told me I was perfectly healthy—except my breathing was a little shallow. That didn’t surprise me. I’d been smoking for twelve of my 32 years, and my father died of lung cancer in his early fifties. That’s why I was having my first physical in five years: I’d decided it was time to stop for good.

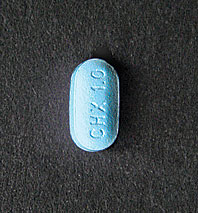

I’d heard about Chantix, a relatively new drug from Pfizer that blocks nicotine from attaching to your brain receptors. That way, you stop receiving any pleasure from cigarettes at all—even as the drug, snuggling up to those receptors the same way nicotine does, reduces withdrawal cravings and unleashes a happy little wash of dopamine to boot. Wonderful things they can do nowadays.

My doctor wished me luck as he wrote out the prescription, telling me it was the single most important decision I’d ever make in my life. I had the medication that night, 35 minutes after dropping into Duane Reade. While waiting, I gleefully chain-smoked Parliament Lights. One of Chantix’s big perks is that you can smoke for the first seven days you’re on it (most people take it for twelve weeks)—more than enough time, I thought, to say good-bye to an old friend.

I swallowed my first pill the next day before work. It was a beautiful fall morning, an almost obnoxiously cinematic day to turn over a new leaf. But by the time I was halfway to the office, I started to feel a slight nausea coming on. Of course, that is a common side effect, as are constipation, gas, vomiting, and changes in dreaming. These five symptoms were emblazoned in a large font on the patient-information sheet.

My stomach settled as I finished my first cup of coffee. I slipped into my boss’s office, proudly announcing that I’d just started taking Chantix. “You’ve probably seen the commercial,” I said. A CGI tortoise races against a sprightly CGI hare, while a paternal voice-over reminds us that quitting smoking “isn’t for sprinters … it’s all about getting there!” Clinical trials demonstrated a whopping 44 percent of patients were still off cigarettes after twelve weeks, the ad says. The tortoise winks knowingly.

“You know, I saw something about Chantix,” my boss said, sounding vaguely concerned. He tracked down the story on a CBS Website. It was a sensational report on Carter Albrecht, a Dallas musician formerly with Edie Brickell & New Bohemians. Albrecht had started taking Chantix with his fiancée, with seemingly dramatic side effects. She claimed he had had bizarre hallucinations that worsened when he drank. One evening, he attacked her, something he’d never done before. He then ran to his neighbor’s house and kicked at the door, screaming incomprehensibly. The neighbor was so panicked he wound up shooting Albrecht through the door, killing him.

I tried not to roll my eyes. It seemed obvious this was nothing more than scaremongering—perhaps Big Tobacco had launched a spin campaign. Millions of Americans were on Chantix. Why focus on the negative?

The next night, I nodded off listening to Radiohead’s In Rainbows, feeling a little guilty that I’d paid zero dollars for it. I had a quick blip of a dream: A dark, inky fluid was jolting violently from the corners of my ceiling, zigzagging its way across the walls and wooden floor in jerky sync to the music.

It was only a dream, though it seemed more immediate and visceral than my usual fare, which I rarely remember after waking up. The following night, things got even stranger. I fell asleep with Bravo blaring on my TV and dreamed that a red-faced Tim Gunn was pushing me against the wall. “But I always thought you were so nice,” I said.

By night four, my dreams began to take on characteristics of a David Cronenberg movie. Every time I’d drift off, I’d dream that an invisible, malevolent entity was emanating from my air conditioner, which seemed to be rattling even more than usual. I’d nap for twenty minutes or so before bolting awake with an involuntary gasp. I had the uneasy sense that I wasn’t alone.

I smoked a cigarette, then tried going back to sleep. But each time I started napping, I’d dream that something increasingly ominous—carbon monoxide? Vampires?—was sucking vital essence out of me. Soon the clock on my desk read 3:20 a.m.

The most unsettling thing about sleeping on Chantix is that I never felt like I was truly asleep. Some part of me remained on guard. It was more like lucid dreaming, what I thought it might feel like to be hypnotized. And it didn’t entirely go away come morning. As I showered, shaved, and scrambled into clothes, I tried to shake a weird, paranoid sense that I’d just been psychically raped by a household appliance.

On January 25, Pfizer was able to share some good news: Japan—where 40.2 percent of all men still smoke—had green-lighted the manufacturing and marketing of its smoking-cessation drug. But a few days later, the Chantix news was less cheering. On February 1, the Food and Drug Administration warned that Chantix, which had fourth-quarter sales of $280 million (up from $68 million a year ago), could cause serious psychiatric problems, including suicidal thinking. Several weeks earlier, Pfizer had independently changed the small-print booklet that accompanies all drugs to say “All patients … should be observed for neuropsychiatric symptoms including changes in behavior, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.” (Previously the fine type had listed suicidal ideation as a rare adverse reaction.)

Now, after investigating an escalating number of complaints from doctors, patients, and health-care providers, the FDA was citing 34 suicides and 420 instances of suicidal behavior in the U.S. Couldn’t those cases have had to do with depression brought on by nicotine withdrawal, compensatory dopamine notwithstanding? Perhaps, said the agency, but some occurred among people who were still smoking while taking the pill.

Varenicline, Chantix’s chemical name, was approved by the FDA in 2006. In development for over a decade, it is the first smoking-cessation medicine designed to work specifically on nicotine receptors, and at first glance, it would appear that it performed quite well in testing. “At week 12, we looked at how many of the smokers didn’t touch a cigarette for the last four weeks of treatment,” says Dr. Anjan Chatterjee, a medical director at Pfizer. “Forty-four percent.” But the tortoise in the ad doesn’t say how patients fared later on. “About 23 percent still hadn’t taken a puff from week 9 to week 52,” Chatterjee admits. “So the relapse rate was about 77 percent.” Still, that’s not bad given that only 7 percent of smokers using the nicotine patch or gum are still off cigarettes after six months.

A total of 3,659 people were handpicked for the Chantix tests before it came on the market, an almost equal number of men and women, with an average age of 43. Nearly all were white, and the tests excluded anyone with a history of depression, panic disorder, heart disease, kidney or liver problems, alcohol or drug abuse, and diabetes. These exclusions aren’t mentioned in the original “Who Should Not Take Chantix” part of the patient-information sheet, which merely states that the drug wasn’t tested on people under 18. (Pfizer does tell patients they should let their doctors know if they have kidney problems or take insulin.)

For me, self-destructive fantasies began cropping up as cartoonish flights of fantasy—nagging chatter that became a little more concrete with every passing day.

Around 5 million prescriptions have been filled in the U.S. thus far. So why would so many groups have been excluded from the testing, particularly for a drug with such potential mass appeal? “In order to satisfy the FDA’s criteria, we have to isolate all the different variables that could affect the outcome,” says Chatterjee. “We can’t use very sick people or people who would not tolerate the drug.” An FDA spokesperson acknowledges this: “It’s not unusual to exclude people with major medical or psychiatric illnesses from some clinical trials,” says Susan Cruzan.

“When they tested the drug, the sample they chose simply isn’t representative of the people they’re targeting,” says Dr. Daniel Seidman, the director of Smoking Cessation Services at Columbia University Medical Center. “By excluding drinkers, you’re artificially inflating your results, potentially. I run a clinic, and two out of three [smokers] I see have a psychiatric or mood problem. None of these people would have been part of the original trials.”

Public Citizen, a consumer-advocacy group, recommends that people not use Chantix—or most new drugs, for that matter—for seven years. “The first seven years are when problems will occur,” says Dr. Sidney Wolfe, editor of Worstpills.org.

“I remember hearing that argument,” Chatterjee said, a few weeks before the FDA’s new warning was issued. “And it’s just so illogical. If no one uses the drug for seven years, there’s no one to report experiences at the end of seven years—so you’re exactly where you were at the beginning.”

While I was on Chantix, I didn’t scan Websites for news about it. As my dream life continued plunging into strange and increasingly grotesque territory, I did think of Carter Albrecht a couple of times, but his story still seemed strictly outlier, a freakish occurrence. As Chatterjee would explain, “What we know of the story has only come from the press. But the level of alcohol in his body was over three times the legal drinking limit in Texas. In the controlled clinical trial, these kinds of changes in behavior were extremely rare, occurring almost as often as the placebo. Based on the tests, we have no evidence of any kind of consistent relationship between Chantix and aggressive behavior.” Nor was the rate of depression any different between those taking Chantix and those on a placebo.

It wasn’t until after I’d stopped taking Chantix (and switched to the patch) that I would read about other cases, ones in which violence was directed inward rather than out. In December, Omer Jama, a TV news editor in the U.K., slashed his wrists and died, a few weeks after going on Champix. (In the U.K., Chantix is known as Champix, but the FDA objected to that name because it was “overly fanciful and overstates the efficacy of the product.”) Shortly thereafter, a 36-year-old welder hanged himself after completing a thirteen-week Champix regimen.

The term suicidal ideation looks pretty dead on the page, and if you were ever to experience such a symptom, it’s unlikely you’d pick up on it right away: “Here comes that damned suicidal ideation again. I had better call my physician.” For me, self-destructive fantasies slowly began cropping up as cartoonish flights of fantasy—nagging, almost imperceptible chatter that became a little more concrete and domineering with every passing day.

A week into my Chantix usage, I started to feel as if the city landscape had imperceptibly shifted around me. Mundane details began to strike me as having deep, hidden significance. The neon arch above McDonald’s: The lights blinked on and off in some sort of pattern, and I needed to crack the code. One of my co-workers was messing with some papers: What is he trying to imply with all that damned crinkling? Sitting in the subway: A man hurries to get inside. His hand, holding a cup of coffee, gets stuck in the closing door. I watch the hand wriggle. The lid bursts open and steaming brown liquid hits the floor. Fingers twitch and splay. Coffee splashes in crisscrossing slats through the subway car. It was a sign—something bad was going to happen.

It felt as if the essential barrier between reality and my imagination had eroded. Was it because I wasn’t getting enough R.E.M. sleep, so my dream life was rebelling, pouring into daylight, insisting to be attended to, one way or another?

Meanwhile, smoking cigarettes had become an exercise in futility. At work, I’d put on my coat, head out, and light up—but there was no pleasure to be found, just a truly nasty taste.

One afternoon, I was typing away at advertising copy, and as I did so, I began to wonder how I had succeeded in fooling myself that my life had any sort of value at all. Writing? Sure, it was what I’d wanted to do since I was 6—but at the end of the day, who cared? Maybe I should just go downstairs and leap in front of a tour bus. Or launch my head through the computer screen. All this seemed logical, but also weirdly funny, even at the time: I could see how crazy these impulses were, I could recognize them as suicidal clichés. But I couldn’t make them go away.

I’d wake up with my clothes on, music blasting, and strange half-eaten sandwiches lying on the floor that I had no recollection of buying.

A few minutes later, they did, and I thought, Who was the depressed seventh-grade goth girl who had just muscled into my brain? I hadn’t thought of suicide in any serious way since I was a teenager, and that had just been adolescent posturing. I had no interest in killing myself—that’s why I wanted to quit smoking in the first place.

Seidman, who has seen only a handful of patients on Chantix, says that “one guy said he was having waking nightmares—actually experiencing nightmares while he was awake.” Last week, Dr. Mary O’Sullivan, the director of the Smoking Cessation Program at St. Luke’s–Roosevelt (who, like Seidman, says she has no ties with Pfizer), saw her first Chantix patient with “suicidal ideation.” This “was quite a shock,” she says. “He had no background in mental illness, no underlying tendency to depression.” However, before then she had “given it to well over 200 patients without a single side effect.” And she still believes that in terms of smoking cessation, “it’s been a miracle drug.”

“I haven’t seen suicide in patients, and I haven’t seen psychotic breaks, either,” says Dr. Elliot Wineburg (also no Pfizer affiliation) of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. “But as far as people successfully quitting smoking, I also haven’t seen great results.”

My own, spectacularly unscientific survey of people on the drug was equally mixed. “It’s getting easier by the day,” says Nicholas Bullock, a 27-year-old art director. “And the nausea has stopped as well.” Others said Chantix worked but left them feeling temporarily lobotomized. Chris Masters, a 26-year-old investment-firm manager, began experiencing “daytime hallucinations. In the car, I’d feel my cell phone vibrate and roll the window down.” On the way to a wedding in the country, “I decided I would plow into a herd of sheep if the street I was looking for didn’t come up soon.” And then there’s Elizabeth McCullough, a 48-year-old musician. “Chantix made me desperately suicidal, just crazy,” she says. “I joked to my friends that Chantix was the ultimate quit-smoking drug, because when you kill yourself, there’s no chance of relapse.”

Since the FDA’s announcement, those hare-and-tortoise commercials seem to have disappeared from the airwaves. Is the voice-over being retooled? “Yes, we’re currently updating our branded campaign in order to reflect the changes to the label,” says Francisco Debauer, a Pfizer spokesperson. “In the meantime, we’ll be airing our unbranded ad in TV and print”—the My Time to Quit campaign, which never mentions Chantix, but directs people to a Website that eventually leads to them to another, which does.

The drug would appear to be at a crossroads—perhaps the worst, rarest adverse reactions have been reported, perhaps more cases are still to come. Pfizer says no lawsuits have been filed, but there are certainly injury lawyers hungrily putting up Chantix Webpages. Smokers who want to quit are left with a more difficult decision—and the strong advice, if they do take the drug, to be on the lookout for mood changes.

After a few weeks on Chantix, I had managed to stop smoking altogether—but it didn’t feel like a triumphant turn of events. I’d become rather reclusive, avoiding calls from friends, and basically just shuttling back and forth between my office and my apartment. I began to dread six o’clock; it meant I had to walk through the streets again. The subway was now out of the question; it made me too nervous. I stopped going to the gym, too.

I wondered whether Chantix was zapping my brain’s pleasure-delivery system to such a degree that not only did I find no reward in cigarettes, but I also found no reward in socializing, exercising, writing, or any of my usual self-stimulating tricks. I’d pace the floor, sit on the bed, channel surf, pace some more, try to read, but the room had a stale, sinking feeling. Maybe I should go and grab a drink—then at least I might be able to get some rest.

There was no warning against drinking while on Chantix, and even if there had been, I can’t say with any honesty that I’d have adhered to it. (I wasn’t taking any other medication, though.) But while I’ve had my fair share of dark and drunken nights over the years, what I experienced on Chantix was something else altogether. One evening, I steeled myself to go on a date, but after a few drinks with the guy, I abruptly burst into tears mid-sentence. The crying jag lasted about 30 minutes, with the thought I can’t do this anymore looping through my head. This was happening a lot lately, as though someone had spliced other people’s thoughts into the tape whirl of my brain.

Another night, at an East Village bar, an older man in a trench coat caught my attention. I chatted him up for a while, until I realized I was actually trying to go home with the shadow cast by a potted plant. With alcohol in my system, I was somehow able to take this hallucination in stride: “The man who got away … ” But that same evening ended with my taunting a skinhead who was improbably on the corner of Avenue A and 14th Street. “You must be lost,” I snapped. “Are you looking for 1993?” He ended up chasing me into a deli and saying he was going to murder me. (The guy at the register called the cops and the skinhead fled, so I’m fairly confident that he, at least, was real.)

I’ve blacked out a handful of times before, but now it wasn’t unusual to have five or six hours completely wiped out of my memory. I’d wake up with my clothes on, music blasting, and strange half-eaten sandwiches lying on the floor that I had no recollection of buying. One morning, I found an unopened container of dental floss in my coat, as well as a batch of business cards from people whom I couldn’t remember at all. Later that day I received a text message: “I had a great time meeting you … I could have talked to you for another two hours. :)” I have no idea who that person was.

Why didn’t I just stop taking the drug? I did consider it. But there’s something particularly dispiriting about quitting a medicine that’s supposed to be helping you quit smoking. I kept thinking that my body was still getting used to being on Chantix and off cigarettes, that I should wait until everything readjusted itself.

A few nights later, a friend invited me to a party and I reluctantly agreed. I was still avoiding my closest friends for fear that they’d notice changes in my behavior. But maybe I’d feel better if I stopped keeping to myself, for just a night. At the party, I tried to impersonate myself as best I could, but I found myself staring and nodding blankly, actually having difficulty understanding what people were trying to say, and getting oddly touchy at offhand comments.

I was offered a piece of cake on a plate and a fork. For the life of me, I couldn’t figure out the puzzle. How the hell were these pieces supposed to fit together? Fork. Plate. Cake. What sort of maniac would present me with something like this at a party? I abandoned the cake for a vodka tonic, which I drank in silent rage.

I left without saying good-bye. In the cab, I watched the city slash past the windows and was tempted to just throw open the door. Running up the stairs to my apartment, I barely had the door open before the crying started again. I sat on the edge of the bed, doubled over, and I felt severely ill, as though some freakish primal despair had finally been loosened from my stomach. The sensation was more like vomiting than any sadness I’ve ever experienced, and the shrieking sobs were punctuated by sudden jags of rage. Like a spoiled teenager, I’d suddenly uproot drawers from the bureau, push all the belongings off shelves with a sudden swat of the arm, smash a glass against the wall, and then the crying would take over yet again. Meanwhile, the room seemed to be pulsing and reverberating around me, and my eye would keep zeroing in on objects—the television, the AC, a pair of shoes—and feel as though they were somehow buzzing with life and gleefully watching me endure the biggest meltdown I’d ever had. I had somehow ruined myself, and suicide seemed like a good way to avoid the embarrassment of this fact’s being exposed.

The next morning, I called in sick to work and started cleaning up the considerable mess I’d made. I had to throw out a bunch of broken CDs, smashed glasses, torn clothes, ripped photographs, and the remaining boxes of Chantix from my medicine cabinet.

It was a good call, I think, the second most important decision I’d ever make in my life.