Joe Bruno has his loafers off in his vast sanctum on the New York State capitol’s third floor. He saunters around on the plush white carpet in dress socks. There’s a set of dueling pistols and pictures of himself in political postures, at groundbreakings or saddled up on one of his eight horses at a parade, in his Stars and Stripes cowboy shirt. Many of these pictures were taken a while ago, but Bruno, who will be 79 next month, somehow looks like he hasn’t aged. There are three golf clubs in his office and a green Astroturf mat against one wall. Bruno picks up a five-iron, checks his grip, pulls the club back slow, and rips a clean, full swing.

“Ohhh.” He stretches his back. “Ahhh.” He puts down the club. “See, that’s the problem. You should warm up when you do that shit. When you’re my age, you have to warm up.” He then plumps down in his cushy chair, picks up an empty water bottle from his desk, and wings it across the room at the garbage can.

Clank! A miss.

“Shit, first one I missed—first one I missed out of four,” Bruno says. “Now, that’s disturbing.”

Bruno is the most powerful Republican in New York. He has been the majority leader of the State Senate for twelve years, one of the so-called “three men in a room” who decided what, if anything, got done in Albany. The other two are State Assembly Leader Shelly Silver, a Democrat, and the governor, who was get-along Republican George Pataki until Eliot Spitzer came in, determined to change the way business was done in the statehouse. For the zealous governor, Bruno represents everything sclerotic and unprincipled in Albany. Spitzer’s been determined to get rid of him. Now, it may not be long before that happens.

On February 26, Bruno and the Senate Republicans lost a special election up in the North Country district, a rural swath of farmland along Lake Ontario that has been dominated by the GOP for 120 years. Money and manpower had been pouring into the area from both parties. The Democrats, led by Spitzer operatives, had a better candidate, a local dairy farmer named Darrel Aubertine, and a better machine. With this defeat, Bruno’s hold on the Senate has been reduced to one vote. All the Democrats have to do is flip one guy, or win another seat this fall, and they’ll have control. Says one Democratic operative: “If a cat has nine lives, Joe’s had 30. Eventually, it’s up.”

Up until last week, Bruno had been beating Spitzer in a war he says he never wanted. Bruno remembers the first time they met. Spitzer was attorney general. “I liked him. He was charming. Direct. Looked me right in the eye,” he remembers. He says they talked regularly during Spitzer’s campaign and “he says we’re partners, says we’re both going to govern together.” Bruno says he was shocked when Spitzer didn’t mean it. “I never saw the other side, that the man doesn’t think straight, that the man has a quirk in his mind. There is something wrong with his mind. He doesn’t think like most. He’s two-faced. He does not tell the truth. He looks you in the eye and tells you something that is totally untrue.”

In his determination to send Bruno packing, Spitzer did almost everything wrong. He was accused of using the state police to improperly obtain records on Bruno’s use of a state helicopter, and he didn’t help anything by allegedly telling a Republican lawmaker that Bruno was “an old, senile piece of shit,” especially at a time when Bruno’s wife, Bobbie, was dying of Alzheimer’s. Spitzer turned Bruno, once deemed a steward of Albany dysfunction, into a working-class underdog; in turn, the high-minded prosecutor-governor was redefined as a thuggish weenie. “He thought Bruno’s guile was easy to understand, but Bruno is defined by his ability to find creative ways to get through complicated problems,” says one source close to Spitzer. “These guys outdanced us on a lot of issues.” Until last week.

There are other things that are throwing off Bruno’s office putt. The FBI is expanding its two-year investigation of him. They dropped a new round of subpoenas on local labor unions to determine why some may have invested millions in pension money with a Connecticut firm Bruno worked for on the side, Wright Investors’ Service. Bruno insists he hasn’t done anything wrong, but he was worried that if the Feds looked long enough they could find something. “Who the hell knows if, inadvertently, there’s something there—that they uncovered, that they want to accuse you of,” he says. “That’s on my mind. I think, What the hell could they get somebody to say that I said or did? I know that’s what they try and do. They tried like hell to intimidate a couple of people.”

If he’s indicted, he could get ousted, even if he’s innocent. If he’s convicted, he could go to jail.

For inspiration in this time of need, Bruno does what he’s always done: He recites a poem—“It’s Lord Byron, I think”—to himself. “Fight on, my men / I’m wounded but not slain / I’ll lie me down and bleed awhile / Then rise and fight again.” Then he repeats it. “You know how many times I’ve said that to myself when I’ve been bleedin’? That’s been my life. I bleed. I rise. I fight again.”

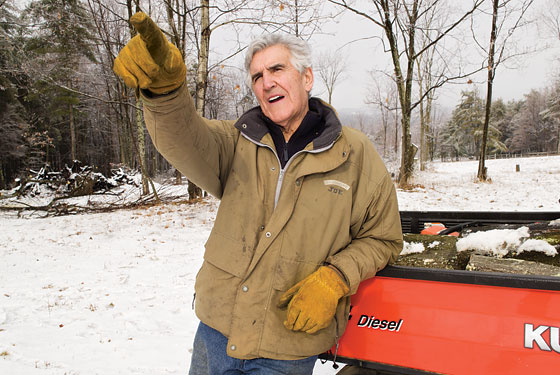

Bruno doesn’t come to the capitol if he doesn’t have to. He prefers to work from his farm, a 125-acre spread in the town of Brunswick, a twenty-minute drive away. His office is tucked inside a cozy A-frame cottage. He takes me in through the basement, which is where he keeps his speed bag, part of his early-morning workout. He straps on a pair of training gloves and starts to punch. First the left. Whap! Then the right. Thap! Then together. Then harder. Then faster. Bruno was his division’s boxing champion in Korea. He throws his punches from the shoulder, just like the pros do it, rocking in rhythm. Whapatathapatawhap …

“I’ve always been a physical person,” he says, moving on to the heavy bag, which hangs from the ceiling on a chain. “I’m just physical. If I couldn’t be physical, I’d be cooked.”

He is “indefatigable,” says former U.S. senator Al D’Amato, and Bruno’s stamina was a critical factor in staging and winning the “Thanksgiving Day Massacre” of 1994. The target was Ralph Marino, then majority leader. Marino “had lost his way,” says D’Amato, Bruno’s ally in the coup, and wasn’t supportive of their man for governor, Pataki. Not three weeks after Pataki won in November 1994, Marino went to his mother’s house for Thanksgiving. When he returned, he was no longer majority leader. Working the phones throughout the holiday, Bruno, D’Amato, and their band of loyalists had secured enough votes for Bruno to take over. It is the only time in state history that a majority leader had been overthrown.

Bruno developed a reputation among his allies as a playful, reasonable power wielder. “A leader’s leader,” says D’Amato. “His motivation is a sense of fairness.” He and Mayor Michael Bloomberg are golf buddies. “He’s a fourteen handicap. I’m a sixteen. He hits the ball pretty good,” Bruno says. “But I’d be a pretty good fourteen too if I played as much as he does.”

“He’s a decent golfer. Scrupulously honest in golf,” says Bloomberg. “He’s just the most honest, straightforward person you can meet. If Joe tells you he’ll do something, you can take it to the bank. When he disagrees with you, he will tell you. If he says he won’t talk about it publicly, he doesn’t. If it sounds like I like the guy, I do, and I respect him. He’s a working-class guy who worked for everything he’s ever had.” Bloomberg is one of the State Senate Republican’s most generous financial supporters; in turn, Bruno has delivered key political cover for many of Bloomberg’s projects, such as congestion pricing and gun control. “He’s just fun to be with,” says Bloomberg. Bruno makes them popcorn when they get together.

Even Bruno’s adversaries admit he’s got his charms. Says a Spitzer lieutenant: “For two guys who couldn’t be more different in terms of pedigree, they both share a love of the fight. What the governor doesn’t like are pussies, and Joe is definitely not a pussy.”

“I have grown to like him,” says Silver. “He is very warm, very good with people. He has tremendous patience with his conference.”

Bruno is chummy with Silver but lost patience with him decades ago. “The reason we have dysfunction in Albany is Speaker Shelly Silver,” he says. “That’s why. He will not govern. His style is to do nothing, hold you hostage, make you grovel, then trade you for what he wants. He kills everything.”

Silver’s response: “Tell him that is governing.”

Over time, Bruno’s politics have turned from Rockefeller Republican to radical self-preservationist. “I have had to get more moderate,” Bruno says. “You can’t be, in this state, an extremist. Not and survive.” Bruno’s most controversial, and productive, alliance is with the state’s powerful health-care-workers union, SEIU 1199. Bruno sealed this pact by taking then-leader Dennis Rivera on a horseback ride. “This is the reason they call me a liberal,” Bruno says. “Guess what? I’ve met thousands of these workers. A sick parent can break up a family. Make your life miserable. I know. I lived with it for eleven years. These workers are the lowest-paid people in the health-care-delivery system. They change bedpans. They change linen. In my heart, I feel it’s wrong to pay these people $8 an hour. So they call me a liberal. So what?”

Bruno has secured cash and provided legislative support for the unions; they, in turn, have served as foot soldiers for Bruno’s Senate races. “He basically out-lefted the left” by forming an allegiance with labor, says one Democratic operative who often went to war against Bruno. “A lot of what he stands for is repugnant to me, but as a practitioner of the sport, in the raw exercise of power thereof, the guy is a fucking master.”

Bruno’s own triumphs as a lawmaker have not been legislative. Asked what bill he’s most proud of passing, Bruno stops to think. “The lemon law,” he says. It protects customers from buying used cars that don’t work, and passed in 1983.

Ask him about his legacy, and he’ll point to his mastery of the pork process. “Take a look around Albany. Take a look around Troy. Take a look at the airport. Do you think that airport would be there if I wasn’t the leader?” he says. “You know how the airport got there? We’re trying to close the budget and Shelly wouldn’t close. So Pataki says, ‘What’s it take to close?’ Shelly says, ‘I need a library in Brooklyn.’ ‘How much?’ Shelly says, ‘$65 million.’ Pataki says, ‘Well, that’s all right.’ It was a $100 billion budget. So I said, ‘It’s not okay with me. I don’t have a single member in Brooklyn.’ ‘So what do you need?’ ‘I need $65 million for the airport.’ Pataki says, ‘Shelly, do you care?’ ‘No, I don’t care, as long as I get my library.’ Pataki says, ‘Good. Done.’ ”

Back at the A-frame, next to the boxing gear, there is, under a canvas cover, one of Bruno’s latest purchases: a Mercedes convertible, candy-apple red. “Isn’t she a sweetie? Got her on eBay.” Next to the car, past his bag of Big Bertha golf clubs, is a large, circular, retro-looking hunk of plastic and coils. It looks like a spaceship. It’s a tanning booth. His daughter Catherine once owned a tanning parlor. “I fire her up, pop in once in a while.”

Upstairs is an addition he had built: a solarium with sauna and Jacuzzi. Bruno dips his finger in. “I keep it at 104 degrees.”

There’s an office phone by the tub. Through the windows, you can see his land with the mountains behind the trees, framing the view just so, and the endless fences for his horses in the foreground. “Is that beautiful?” he says. “You sit here, at sunset, or sunup, and watch these horses grazing, chasing each other, running around. It’s just the prettiest thing you ever saw.”

Bruno grew up without any of this, in Glens Falls, a blue-collar town north of Albany. His father shoveled coal at a paper mill. “When I was a little boy, we had pony rides down the street,” he says. “Rides cost 5 cents. Never had it. I watched all the other kids, you know, climb on those horses. I promised myself I would always own my own horse.” His mother was sick when he was a child. She had a gallbladder infection. When the doctors operated, they accidentally cut her bile duct. Seven surgeries later, she passed away.

His first job was at a bakery. He carried trays of pastries to the factory workers for their morning shifts. His pay was what they didn’t eat. In school, he was a failure. “They sort of kicked me along, you know? I told Sister Rose Madeline I wanted to be an altar boy. She laughed at me. Nothing worse. She said, ‘He’s too dumb.’ ” On summer afternoons, he learned to box. A middleweight met him in the park. “He’d get down on his knees and I’d circle around him and he’d wear out his pants circling on his knees. He taught me to punch straight and lead with your left. These kids that used to bloody my nose, I kicked the shit out of them.”

That’s about the time he met Barbara—known as Bobbie. He was 14. She was 13. They met one night at the YMCA, playing Ping-Pong. This was 1947, and Bruno’s job was driving an ice truck. Her father was a surgeon and chief of staff at the hospital, and didn’t approve of him. “Her father said the only way he’d agree to our getting married was if I would live there while I was in college.” He enrolled in Siena College and drove the ice truck to class.

Bruno’s break came when the owner of the ice company wanted to sell his route. “I begged. Give me a chance. Pleeasse.” He did. “I worked five in the morning till ten. I was making over $300 a week. More money than I seen in my whole life. When I went and got her engagement ring, I had dollar bills. I was laying them out, they were soaking wet from the ice.”

After Korea, he came back and sold encyclopedias and frozen-food plans door- to-door. “These were one-night closes, no callbacks.” Customers pushed him out of their houses. When he rang, they dumped water on him from upstairs. “That was really my training in politics,” he says. “Selling. That’s what life is.”

The tour of his farm continues to the living room. A hospice nurse walks in. She had been upstairs, taking care of Bobbie. “Saddest thing you ever saw in your whole life,” Bruno says. “I don’t think she weighs 85 pounds. I don’t think she knows me anymore.” It was January 6, a Sunday. Bobbie died the next evening. They had been married for 57 years. “She gave me my chance,” Bruno says. “She believed in me.”

Bruno started out a businessman. He bought and sold horses. He co-founded a high-tech phone company, which he was hoping to sell and make millions from. He joined the young Republicans because he believed in less government and felt the wealthy crowd would be good for his business. He could sell them stuff—stuff they could show their wealthy friends. “I always had it in my head, like owning a horse, that I wanted to be in public service,” he says. “I wanted to do things for people.”

“I used very bad judgment. Paid all my attention to the Senate. Let all my business interests go,” Bruno says. “Twelve years ago I was worth a hell of a lot more than I’m worth today.”

In 1969, he volunteered for Perry Duryea’s campaign for Assembly. Bruno was such an efficient foot soldier that Duryea, who became Speaker, offered him a job as special assistant for personnel. Then Bruno ran for county chairman and won. Then a State Senate seat opened up, and he ran for it and won. To date, Bruno has won sixteen straight elections, and the friendship of people like Donald Trump, who lets him use his Mar-A-Lago estate in Palm Beach for fund-raisers.

Sometimes he spends more than he raises. In 2006 and the first half of 2007, Wayne Barrett, an investigative reporter at The Village Voice, found that Bruno spent $55,000 on a Mar-A-Lago fund-raiser and raised far less. Committee receipts also showed a remarkable $92,000 for meals and meetings at Albany institutions like Jack’s Oyster House in the same period. Within that lot, there were receipts for $18,225 at the Saratoga Raceway, mostly filed during the summer racing season, from the track, every other day.

“I don’t think Joe Bruno has paid for his own lunch since he came into power,” Barrett says.

But Bruno says this is how he gets things done. “I’m campaigning year-round, you might say,” he says. “I’m right in my own district. Every time I go into a restaurant, I’m shaking 20 or 30 hands.”

Bruno’s point of view is that he could be richer than he is, if not for the Senate. Because of his increasing political responsibilities, he resigned from his phone company, and it tanked. This still irks him. “I used very bad judgment. Paid all my attention to the Senate. Let all my business interests go.” He’s convinced public service has cost him, requiring him to keep his investments in blind trusts that leave room for his partners to make mistakes. “I’m probably the only guy in a high political office that’s worth a lot less than when he took that high political office. Twelve years ago I was worth a hell of a lot more than I’m worth today.” Even his side gigs, deals with friends and investments, have bombed, he complains. “In the last twelve years, about every deal I’ve made I’ve lost money on.”

He was introduced to executives at Wright Investors’ Service by a mutual friend over a decade ago. His relationship with Wright is the subject of the FBI investigation. “I took a look,” he says, and found the company to be “small, neat, clean, pristine.” Bruno signed on as a consultant. “I provided the entrée. In that business, the biggest problem is access. I provided access.” Bruno, who makes $121,000 a year in salary as majority leader, believes there is nothing improper about steering people he does business with in politics to open portfolios at Wright. There was no quid pro quo, he says. If Wright wanted to meet with trustees of a union looking to invest pension money, Bruno would make the phone calls. “My pitch to them was, ‘If you like what they have to say, take it to the next level. If you don’t, say good-bye.’ ”

It’s an arrangement the Times editorial board has called “unnecessarily sketchy.” Russ Haven, NYPIRG’s longtime Albany watchdog, says Bruno has mastered the art of riding the “seams” of what he can do to make money on the side, but not break the law. “Ethical behavior is about actual conflict, but also the appearance of conflict,” Haven says. “For business and union people to be steered by a public official to a vendor could create the impression—on them and the public—they might get better access or continued access to what they currently enjoy, or something more. And that’s troubling.”

Bruno insists none of his consulting clients got special favors. “Guess what?” he says. “Some of the people I introduced them to lost. My biggest account invested over $120 million. They lost the whole thing. Why? Poor performance.”

It’s a curious argument. “It’s not the outcome of any outside transaction that’s the problem per se,” Haven says. “It’s the inference that doing business with Joe Bruno the consultant might help you with Joe Bruno the majority leader. It’s a variant of pay-to-play.”

When Spitzer came into office in January 2007, “most thinking people thought we were going bye-bye,” says Bruno. How could the Republicans win back any seats with their leader under investigation by the Feds for moonlighting as a consultant? Yet only one Republican senator spoke out against him. They remained loyal. Plus, many thought Spitzer was an obnoxious bully who could self-destruct. “He is our greatest ally,” Bruno says.

Bruno has an arsenal of stories about what he sees as Spitzer’s looniness. His favorite is probably the one where the governor accused him of “abusing” Senate Minority Leader Malcolm Smith through a parliamentary maneuver. “You know,” he says he told Spitzer, “Malcolm Smith has his head so far up your ass he can’t even see straight.” Spitzer “really lost it,” Bruno recalls. “He said, ‘You have just insulted the governor of the State of New York! I’m calling the New York Times! Mr. Bruno, get out of my office!’ ”

Bruno says he just sat there for a moment, then jabbed. “I tell Malcolm every day what I just told you and he laughs like hell. Call Malcolm.”

“ ‘I’m calling the New York Times!’ ”

Bruno says he just kept hitting back. “ ‘You know what your problem is? You’re a spoiled brat, an arrogant kid that never got over the fact that when you don’t get what you want you have a tantrum.’ And you know what he does next? He runs out of his own office! I’m thinking, Jesus, where the hell is he going?” When Spitzer returned, the shouting continued. Then Spitzer left again. “Now I’m thinking, Jeez, there’s something wrong with this guy. He’s shouting, screaming until he’s purple. He’s 8 years old.” Spitzer returned for a final time. Bruno remembers his orders from Spitzer: “Get out of here!”

Spitzer’s spokeswoman, Christine Anderson, says Bruno’s recollection is “totally false, and with each retelling his story becomes more embellished.”

While there is no evidence to connect Spitzer to the FBI’s investigation, Bruno is convinced Spitzer is behind it. “Who do you think had the most to gain if I was removed or slowed down?” Bruno says. “I told the FBI: ‘I’ve got a lot of political enemies that would love to get at me, you gotta understand.’ They said, ‘We do, but we have an inquiry from someone with a lot of credibility, and we can’t ignore it.’ ”

Bruno pauses here. “Who do you think has ‘a lot of credibility’? The attorney general, maybe.”

Says Spitzer’s spokeswoman: “There is no truth to this story whatsoever.”

That’s not to say that Spitzer isn’t out to get him. “The way legislative bodies around the world have worked is that in one room you’re trying to collaborate, and in the other room you’re trying to fuck the guy,” says another source close to Spitzer. “You’re collaborating in your governmental duties, and you’re trying to fuck ’em wearing your political hat. And anyone who knows Eliot Spitzer knows he’s going to be political. So if Joe feels hoodwinked by that, he’s dumber than I think he is.”

Others have tried to save the relationship. D’Amato tried to make a powwow at his birthday party. Bloomberg tried to get them together on the golf course. Didn’t happen. “Eliot’s a tennis player,” Bloomberg notes. “Joe is not.” Bloomberg finds the deadlock nonsensical. “I’ve tried to explain it’s in both their interests that they both survive. Eliot doesn’t see it that way.”

The way Spitzer sees it, his survival rests with ousting Bruno. His destiny, even. “You’ve got a governor who came into office on the wings of angels,” says the Spitzer source. “He was the man. And his first year was defined by a scandal and an error. What he wants in years two, three, and four are results. He will not stand for this obstructionist Senate majority leader getting in the way of his results.”

When Bobbie’s condition worsened, Spitzer called. He came for the funeral. Bruno was worried that if he gave her eulogy he might cry, and how could he cry in front of all these people? But he changed his mind and did the eulogy anyway, and he was funny and sweet and he told the old stories about Glens Falls and people who were there said they laughed and cried at the same time.

Other than that, Spitzer and Bruno haven’t spoken in eight months. “The relationship is dead,” the Spitzer source says.

On February 27, the day after the North Country defeat, Bruno is back in his capitol-building sanctum. “We lost the battle, but we’ll win the war; that’s my statement, and that’s the way I feel,” he says. He is having lunch at his desk. “Oysters scampi. It’s just delicious, if you like oysters. I love ’em.” He is eating alone, and that is unusual. Bruno can’t remember the last time he had lunch by himself. He has just come from a press conference to defend his party’s poor showing, and reporters ribbed him about whether he still had any “fire in the belly” and wondered if a coup would form to oust Bruno or if, finally, Bruno would simply retire. “Everybody thinks about retiring,” he says. “Everybody thinks about doing something different.”

But not him. Not now. “I am so energized and so charged up that it’s hard for me to describe my feelings.” He says this, but his tone is flat and he’s chewing his scampi and the battle cry is unconvincing. Earlier, Bruno held a meeting with his fellow Republican lawmakers, half of whom were past retirement age, some older than Bruno. They had been so loyal to him in the past. This meeting was different. “An airing,” he says. “It was a loud discussion, a lot of people sharing points of view, which I invited.” Behind closed doors, the Republican lawmakers talked about what went wrong. Bruno gave a speech, to boost morale, and in doing so he recited his favorite, defiant lines: Fight on, my men. I’m wounded but not slain. I lie me down and bleed awhile. And rise and fight again.

This time, there was protest from one lawmaker. “Don’t talk about bleeding.”

The poem itself is not Byron’s. Its origins are unclear. It was probably first published in 1658, in a collection of traditional English and Scottish ballads. Titled “Johnie Armstrong’s Last Good Night,” it tells the mythic story of a regional warlord summoned before the king of Scotland. He arrives with his armed clan, intending to pledge his loyalty. But the king declares him a traitor. A battle ensues. Armstrong is stabbed in the back. He does not rise and fight again. And all his men die.