Mike Bloomberg may well be, as consensus opinion has it, a strikingly effective problem-solving technocrat, but there’s at least one area in which his administration has plainly, if quietly, failed: homelessness. The mayor walked into City Hall in 2002 vowing to end homelessness as we know it, and eventually promised to reduce the shelter rolls by two-thirds or more. Yet the numbers not only haven’t fallen, they’ve gone up. The most current estimates place 34,776 people in the shelter system, almost 4,000 more than there were at the start of his first term, with another 3,000 or more on the streets. During the last big homeless crisis of the eighties, by comparison, the shelter population topped out at 28,737. “If these were Ray Kelly’s numbers,” says Mary Brosnahan, the executive director of the Coalition for the Homeless, “the city would be in an uproar.”

Yes, the real-estate boom raised rents beyond the reach of many people, and Albany was slow to help the city build new low-income housing. But it was Bloomberg, homeless advocates say, who tried to radically reinvent the way the city engages with homeless people. Only in this case, his ambitious attempt at reform just didn’t work.

The roots of the mayor’s failure can be traced back to the early eighties, when judges in several major lawsuits effectively guaranteed the right to shelter here, making New York the only big city in the nation where no one who needs a bed can be refused one. From Ed Koch on down, every mayor has faced the seemingly impossible task of complying with the courts without bankrupting the city, only inevitably to fail. Bloomberg sought to break the cycle. In December 2004, he launched a radical new program called Housing Stability Plus, or HSP. Under this plan, qualified homeless families still got free apartments, only now they were paid for by the city, not the state or federal government, and the subsidy would disappear over five years. The idea was to take control of the problem and add an incentive to motivate people out of homelessness, and off the dole forever.

The HSP program quickly backfired. The city funded 10,000 new leases for homeless families, but as many as 60 percent of those leases eventually had problems—often because the tenants couldn’t afford the rent when their subsidy was interrupted. Critics say that many HSP families became homeless again, cycling back into the shelter system (though the city disputes this); Bloomberg, they say, was blind to how hard it would be for families to start improving their lives. By mid-2006, the number of homeless families was creeping upward again.

Last spring, the city scrapped HSP and replaced it with a hodgepodge of new housing programs. The new goal is to offer a menu of options tailored to an individual’s needs. One only gives apartments to homeless people who have jobs; another is for homeless people with fixed incomes from Social Security; a third offers short-term help for the recently evicted. It’s too soon to tell if these initiatives are working, but it’s clear that Bloomberg still intends to radically overhaul homeless assistance. “We’re not going to assume everyone needs a long-term subsidy,” says Robert Hess, the present homeless commissioner. “There are an awful lot of families that, given hope and a hand up, and an opportunity, will be just fine on their own and much happier for it.”

Perhaps the administration’s boldest experiment to date involves people outside the shelter system. Bloomberg has put particular pressure on Hess to get the numbers of street people down before the end of his term, and last fall, the homeless commissioner debuted a closely watched plan for people who sleep on subway grates or on stoops or in encampments. Where once the city would have offered a bed to street people only if they agreed to stop doing drugs or enter a mental-health program, now it’s offering them their own apartments first—a shabby but safe single-room unit, say—with no strings attached. The hope is that getting people their own home, however basic, will act as a gateway for them to accept additional help.

The city is claiming at least short-term results; the street-homeless numbers have dropped dramatically, and Hess argues that reducing street homelessness is a better measure of success than reducing the shelter population. But, of course, there are critics. Conservatives say the program is a handout that does nothing to discourage the root causes of homelessness. And although many homeless advocates support the program, some see problems in how it’s being applied. “In many places, they’re relocating vulnerable adults to substandard housing,” says Legal Aid chief attorney Steven Banks. “We’ve seen repeated instances of people having to return to the shelter system.”

From February 4 at 3 p.m. to February 5 at 6 a.m., photographer Jeff Riedel and I combed Manhattan and the Bronx to meet homeless New Yorkers. They weren’t hard to find. Here is a sampling.

Damian 3:30 a.m., Harlem William Thompson 5:30 p.m., the Bronx Lorenzo 9 p.m., the Bronx Connie 2 a.m., Upper West Side Nancy Quinn Midnight, the Bronx Lorraine Zier 5 a.m., midtown

Damian

3:30 a.m., Harlem

It’s known as the Bat Cave, a long alleyway at 134th Street and Broadway, just north of the Harlem Fairway store. In 2006, the city started clearing homeless encampments, including this one. Damian, 38, is one of a few people who have stayed. Tonight, the holdouts are drinking around a fire in a garbage can. Damian’s been living here for two years, and on the street for six. He collects cans for money and washes up at a shelter. He doesn’t sleep there, though. “Every time I got something valuable, they’d steal it,” he says. When his mother comes by the Bat Cave looking for him, Damian hides.

William Thompson

5:30 p.m., the Bronx

Chickens, dogs, and a cat or two roam around William Thompson’s secondhand trailer. They remind him of the North Carolina farm where he grew up. The 63-year-old former drug addict, cancer survivor, and widower has been living for more than a decade on a dirt lot on the Bronx side of the Harlem River. A neighborhood church owns the land; Thompson does mechanical work for local businesses to pay the church $75 a month in rent. His gas generator powers a small refrigerator and lights in his trailer, and a butane-fueled heater keeps him warm. But on cold nights, the butane often runs out while he’s asleep. His previous setup burned to the ground a few years ago. With fuel and food costing him more than $40 a day, Thompson’s $700 Social Security check doesn’t last long. Outreach workers tried for years to get him off the street, but he refused. The police roll by twice a night, so he feels safe. He even has a cell phone. Here, he says, “I’m free.” Just this month, however, Thompson agreed to move into a single-room apartment under the new city program that gives chronically homeless people housing, with no strings attached. Thompson says he’s getting old. “If I catch a cold, I’m gone.”

Lorenzo

9 p.m., the Bronx

Lorenzo is one of a handful of people who live in a shallow space below an on-ramp connecting the parking lot of Yankee Stadium to the Major Deegan Expressway. His section has a ceiling that’s four feet high; he spends most of his time in a sort of permanent crouch, or asleep on one of the mattresses he’s dragged in from the garbage. In the morning he lights a charcoal stove to make coffee and then leaves to collect bottles and cans. On a good day he’ll make $50, most of which, he says, goes toward vodka and beer. “This place isn’t dangerous,” says the 55-year-old Mexican immigrant, who says he started drinking in the sixth grade. “I thought about moving, but the alcoholism gets in the way. That’s the truth.” When city outreach workers first met Lorenzo, he was sleeping under another part of the on-ramp with an even lower ceiling. They had to crawl on their stomachs to talk to him. Now they come almost every night to check on Lorenzo and offer him a place to sleep. Sometimes he takes them up on it. Permanent housing is another matter. The social workers aren’t sure yet if he’s documented; if he isn’t, he’ll have no benefit checks that could pay for a place to live.

Connie

2 a.m., Upper West Side

“I have a lot of names,” says the man sitting under some scaffolding outside a vacant Upper West Side storefront at 2 a.m. Call him Connie, he says—that’s what his father called him. He left home early—his parents had issues, he says—and has been homeless most of his life. He avoids the shelter system and social services. “Paperwork, rules, questions. I prefer getting stuff on my own.” He lives on about $15 a day in panhandled donations. “It’s enough to survive if you can get free clothes, free food.” Until recently he lived near Tompkins Square, “but it’s more civilized here,” he says. The Upper East Side is where he gets the most static: “The cops don’t like it when you’re too close to the mayor’s place.” Connie says he doesn’t do drugs. “There never was a salesman that could entice.” Tonight, he’s eating a mound of moist coffee grounds from a paper cup, like it’s a scoop of ice cream. “El Pico coffee,” he says. “It’s good. It’s like a cough medicine—a multipurpose medicine.”

Nancy Quinn

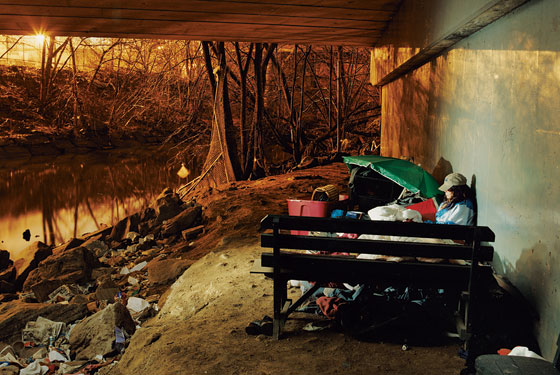

Midnight, the Bronx

For the past year, Nancy Quinn has lived on a long, narrow patch of dirt under a four-lane overpass in the South Bronx, a few feet from the Bronx River. To get there, she walks the length of the overpass, dodges two lanes of traffic, hops over a Jersey barrier, negotiates a steep hill of mud, and steps around a drooping chain-link fence. Her bed is an old box spring she found in the garbage, lined with a sleeping bag and a few comforters. She’s set up two wooden benches on either side of the bed, a plywood table where she eats, bins for her clothes, and a makeshift standing mirror. The river is her toilet. In warm weather, she washes in the river, too; otherwise, she uses a McDonald’s bathroom.

She wears clothes found in the garbage. Tonight, she’s got on a brown baseball cap with a Colombo Yogurt logo and a blue-and-white windbreaker. She’s 39 but looks older. Her hair is long, brown, and greasy, and her pale complexion is marred by a big bruise around her right eye. It’s a souvenir from a fight with someone she owed money. “I was getting something from a dealer, and he saw it and just punched me right in the eye. Broad daylight. I took it, and I walked away. I mean, what am I gonna do?”

It’s a cold night—we can see our breath—but under the overpass, Nancy’s warm. “I got, like, six blankets here,” she says, laughing and coughing at the same time. The river bubbles. The glow of a streetlamp shines on the water like moonlight. “The river’s peaceful to me,” she says. She’s been homeless now for almost four years, moving from place to place. She says she likes this spot the best, but as the night goes on, she talks about the sacrifices she’s made, the three children she rarely, if ever, sees—a teenager, a 4-year-old, and a 2-year-old. Talking about the children makes Nancy cry—long, low sobs.

Soon enough, though, she’s better. “I love to cry,” she says. It’s one of the reasons she won’t take Prozac. “When I’m on the mental meds, I don’t like the way I feel,” she says. “I’m not Nancy.”

This Nancy is a lifelong drug addict, a sexual-abuse victim, and a prostitute. For the past three years, she has awoken most days in the late afternoon with no money in her pocket. She says it’s safer to spend everything she has—you can’t get ripped off that way. She keeps a bottle of water ready to wash her face and brush her teeth. Once she’s cleaned up, she’ll comb the sidewalk outside searching for used cigarette butts—“floor models,” she calls them. “Nicotine is a bitch,” she says. “I’ve got to smoke some nicotine in me before I even try to make any money. Otherwise I’m a real crank. People don’t like me when I’m cranky.”

Then she’ll hit the stroll, up on Bryant Avenue. “I call myself a self-employed street vendor. My license is my HIV-negative paper. You know what I’m saying?” She charges $20 for blow jobs, $30 for sex, $40 for “half-and-half,” which means both. On a good night, she makes between $100 and $150. She spends most of what she earns on crack—$5 for nickel bags, $10 for dime bags. When she comes back to where she sleeps, the sun is usually coming up, and she’ll be “either high or wishing I was.” That’s when she likes to take a hit from her pipe and belt out “my rock and roll shit”: Guns N’ Roses, the Stones, Kiss. She’ll read for a few hours—Dean Koontz, the Bible, whatever’s around—until she’s wound down enough to pass out.

She has one or two friends—a guy she called T came by as we talked and gave her a cigarette when she asked for it—but most of the time, Nancy is alone. “I have no pimp,” she says, suddenly giggling. “You want to hear something bad? You want to know who my pimp is? My stem is my pimp. My crack pipe.”

Outreach workers from the Citizens Advice Bureau, a nonprofit group that keeps tabs on chronically homeless people, come by every few nights to check on Nancy. She enjoys the visits—they’re like social calls to her. But when they’ve offered her shelter, she’s refused. She knows that shelters typically require people to stop using, or at least enter a rehab program or get counseling. “The thing is, when a person wants to get clean, they have to get clean for themselves.”

Last year, however, something happened that started to make Nancy think about getting off the streets. Her oldest son, who’s now 14, reappeared in her life. For a time, Nancy had been hiding from everyone, but her ex-husband and mother-in-law had found her and reached out to her on his behalf, and Nancy finally agreed to see him. He’s been to her place under the overpass a number of times since. She talks about her son like any proud mother. “Oh, my son is gorgeous—a beautiful young man with a beautiful heart.”

But seeing him also reminds her of how far she’s fallen. “My mother-in-law came to me a few months ago and said, ‘Nancy, he’s turning out just like you.’ ” Now she’s crying. “Like, there was this scare with him. My ex got called to his school because my son decided to cut himself and write something like ‘Die’ in blood on the school wall. My son sometimes feels like nobody gives a damn about him. And that scares me.”

Three weeks after I first met Nancy, the outreach team convinced her to accept a free room in an apartment house about a half-mile from the underpass, as part of the new citywide shelter-first initiative. Nancy told me she was tired; she decided to give it a try. The night the outreach workers handed her the keys, Nancy was thrilled. She loved the electricity, the shower. “As soon as I had the keys, I stripped naked and lay down on the blanket. I pulled my book out, and I was lying there reading, and the next thing I knew, it was the middle of the night.”

But at 2:50 a.m. that same night, Nancy was found with half a bag of crack near 180th Street and Morris Park Avenue. She was arrested and charged with a class-A misdemeanor, her 39th arrest on record with the Bronx D.A.’s office. At her arraignment, she took a plea and was sent to Rikers Island for seven days.

I found Nancy again the day after she was released—but below the underpass, not at her new apartment. Since she’d left Rikers, Nancy hadn’t gone back to her new room at all. She’d spent that afternoon turning tricks on Bryant Avenue. We sat by the river together, eating McDonald’s, and I asked her why she came back here, under the bridge. Before she answered, she asked if she could take a break. Then she lit her pipe.

“I don’t want to smoke there,” she said. “I don’t want to bring this there. I don’t want to bring that shit to my home, to my new home, and screw everything up again. I don’t want to do that.”

Then Nancy was crying again. “The things that I’ve done for this stupid shit,” she said. “I’m leaving one home for another.”

But she knows she wants it both ways. She wants to move to start a new life, but not if it means giving up her old life. Here’s how it works, she says: She’ll go to the new apartment after she makes some money and buys some drugs and food. “I want to get nice and high, I need something to eat, and then I can go there and lie down.”

Lorraine Zier

5 a.m., midtown

Lorraine Zier has been homeless since she moved here from Florida three years ago. For most of that time, she’s slept on a grate outside St. Francis House on West 31st Street. Early on, she took city placement in an SRO, but she says her neighbors argued all the time, so she went back outside. Zier makes some money from collecting cans, and she’s eligible for food stamps. An organization called the Midnight Run comes by and gives her clothes. When she wants a shower, she goes to a drop-in center. She gets free meals from several churches and synagogues. When it’s cold, she scrapes together $10 or $12 and buys a round-trip bus pass to Foxwoods or Mohegan Sun, where she can warm up inside the casinos for a day. “I don’t have enough money to gamble,” she says, “but they give you coupons to eat for free at the buffets.” Lorraine says her family drove her to the streets. “They resented me. They don’t care about me. They don’t love me at all.” Would she go home if her family found her and wanted her back? “No,” she says. “I do not love them. You can put that in there.”