The 22nd-floor conference room was packed tight. Stacks of documents and crusty takeout cartons littered the table. On Friday night, March 14, a team of Bear Stearns employees from the $1 billion Global Clearing division holed up in the firm’s Madison Avenue headquarters analyzing their operations until midnight. On different floors, other Bear employees worked to assemble financial information that could tell them how sick the firm really was. The greatest crisis in Bear’s 85-year history was careering out of control. In just five days, Bear’s stock had plunged amid rumors that the firm was out of cash. Perception is reality in business. The market had eviscerated the company, taking half of Bear’s value despite repeated assurances from Bear’s CEO, Alan Schwartz, that the company was in good shape, with a cushion of $17 billion in cash. With Bear on the brink of bankruptcy, JPMorgan Chase and the Federal Reserve extended a financial lifeline and prepared to buy Bear outright.

At the start of the week, Bear’s bankers and traders had begun to sense that something wasn’t right. Rumors of a looming “liquidity crisis,” in Wall Street parlance, spread through the financial system. “We started hearing information of certain clients getting skittish. It started with the small things,” one Bear staffer recalled. By Wednesday, with the stock down almost 20 percent and some banks refusing to trade with Bear, Schwartz, who was attending a conference in Palm Beach, Florida, went on CNBC to stanch the rumors. But his pronouncements had little effect.

Bear’s employees surely knew they were writing the storied bank’s obituary as the weekend dragged on. At Bear’s offices, bankers from JPMorgan stalked the halls, picking through the remains of Bear’s business divisions. Late into Sunday afternoon, Bear’s board, led by chairman Jimmy Cayne, feverishly negotiated the sale with JPMorgan’s CEO, James Dimon, and the Fed. Bear staffers, nearly all of whom had significant wealth tied up in the firm’s cratered stock, were left to wonder just how much Bear would fetch. Fifteen dollars a share? Maybe $20? Only a week before, the stock had been as high as $70, and last January, it peaked at $171. After all, their Madison Avenue skyscraper was reportedly worth more than $1 billion, and the company was projected to earn a profit in the first quarter. The sale to JPMorgan was going to be bad, but maybe they could get out of this with something. Anything.

Around dinnertime on Sunday, March 16, the sale was announced. Up on the 22nd floor, a pall descended over the conference room when the final terms popped up on Bloomberg Television. Bear Stearns, a firm with 14,000 employees, a constellation of offices around the globe, and profit of $2 billion, was being sold to JPMorgan for $2 per share—less than the price of a latte.

“It has got to be a typo,” one senior manager gasped. But it wasn’t.

Shortly after 7 a.m. on Monday, dazed Bear staffers arrived at the Madison Avenue headquarters to absorb the news of their firm’s implosion. They were instructed to call their clients and to begin the transition to be sold to JPMorgan. In the halls, staffers glared at people they didn’t recognize, wondering if they were JPMorgan bankers admiring their new prize. “I think JPMorgan should be rightly worried about stepping foot in the building until people cool down,” one employee said. Down in the lobby, a gallery of onlookers assembled. Real-estate brokers circled like vultures, handing out cards to potential customers who might need to liquidate their holdings. Tabloid reporters hounded employees for comment. One person taped a $2 bill to the front door. What at first felt like a funeral quickly transformed into a Manhattan spectacle, the operatic finale to an easy-money era.

Of course, banking is an up-and-down game. Earning the big money carries the risk that something might go disastrously wrong—“the nuclear scenario,” as one staffer put it. But even by Wall Street standards, the sudden and violent death of Bear Stearns was psychologically unfathomable. “We didn’t think it would ever be possible,” one senior banker said. Bankers who held down million-dollar-a-year jobs had their yuppie union cards stripped away overnight, and the enormity of the loss was hard to swallow. “I lost a lot of money,” one Bear staffer said on the evening of March 18. “It has felt like an Enron, but without the fraud.”

A pillar of Bear’s culture has always been the loyalty of its employees, who invested heavily in the company’s stock. Staffers owned about 30 percent of the company’s shares. One staffer noted that after the crash of 1929, Bear famously didn’t lay off a single employee. “Headhunters called me all the time,” one Bear staffer said on March 19. “I never called them back. I wanted to build a career here. It’s sad to see that go away.”

This wasn’t just rich traders losing their shirts. One Bear banker who left two years ago told me his former assistant, a 22-year Bear veteran, called him sobbing about the news. “She said, ‘I thought I was going to work here until I died. I love this place.’ It’s not about the stock for her. The human tragedy here is enormous.”

If death is followed by the five stages of grief, Bear staffers are deep into the anger phase. The Fed and Jamie Dimon are the prime targets of Bear’s ire. “He took advantage of the situation in ways that were not honorable, by allowing this deal to happen at two bucks and wiping out Bear’s shareholders,” one staffer said of Dimon. Others used the word cutthroat in describing his tactics. Many Bear staffers feel the Fed forced the fire sale to JPMorgan to prove a point. With millions of Americans facing foreclosure on dodgy subprime loans, the government needed to pin the housing meltdown on someone. After all, the Bush administration didn’t want to be seen as bailing out a bunch of wealthy Wall Street bankers at taxpayer expense. “They needed to show there was a victim,” a Bear staffer said. Fumed another, “The whole idea of a couple of people deciding we should go bankrupt to teach somebody—I don’t know who—a lesson? I don’t know how that serves anyone. They just transferred our wealth to JPMorgan.”

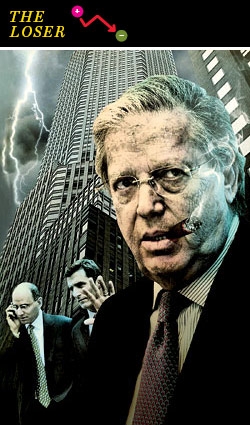

In Bear’s case, the bank’s outsider status worked against it. Smaller, scrappier, perhaps meaner than other banks, Bear Stearns prided itself on its grit and mettle compared to the coddled and polished competitors at Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley. Longtime CEO Jimmy Cayne relished his cigar-chomping image and the fact that he never finished college. In November, The Wall Street Journal reported that Cayne, an avid card player, even indulged in smoking pot during marathon bridge tournaments. Cayne denied the incident, telling the Journal, “There is no chance that it happened.”

If death is followed by the five stages of grief, Bear staffers are deep into the anger phase. Jamie Dimon and the Fed are the prime targets of Bear’s ire. Many feel Bernanke forced the fire sale to JPMorgan to prove a point. Some are wondering if the Fed and Treasury secretary Hank Paulson were only too happy to see Jimmy Cayne go down.

A decade ago, Cayne cemented Bear’s iconoclast status when he famously snubbed the Fed as it rallied other Wall Street banks to bail out the failing hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management. His peers felt betrayed, and the wounds never healed. “Other members of the consortium were upset,” said Robert Merton, the Nobel Laureate who ran Long-Term Capital. When Bear found itself backed into the corner last week, its pleas to the Fed fell on deaf ears. “They don’t have to push you, they just don’t have to help you,” Merton said.

Now some are wondering if the Fed and Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, who was then Goldman’s COO, were only too happy to see Cayne go down when his firm was the one in need of a bailout. “Did the Fed decide Bear Stearns had to fail to get access to the discount window?” one Bear staffer speculated. As evidence, Bear staffers point to the fact that shortly after the Bear-JPMorgan deal closed, the Fed began lending directly to other beleaguered Wall Street banks, a move that would have surely saved Bear had it gotten access to the cash.

Staffers also feel let down by Cayne and Schwartz. They wonder why the two didn’t seek help from foreign funds that bolstered flagging banks like Citigroup last fall. Or, when the run on Bear started last week, why didn’t they demand the NYSE halt trading? “This to me is the arrogance of Cayne,” another former Bear staffer said. “It’s him saying, ‘I don’t need help from others.’ This is just tragic hubris.”

“Jimmy is a real bridge player and poker player,” one former Bear executive said. “The fact of the matter is, Jimmy played his most important hand, and lost.”

Historically, Bear Stearns was a cautious bank. But, because it was smaller and less diversified than other Wall Street banks, Bear was vulnerable to a firmwide crisis if business turned south, and was especially weighted toward risky mortgage investments. And recently, when the firm began ramping up its risk in search of higher profits, Cayne’s outsider legacy was transformed into a liability. Just last summer, two Bear hedge funds melted down, forcing the firm to bail them out with $1.6 billion and leading to the dismissal of co-president Warren Spector, who oversaw the complex mortgage-backed-securities operations. Alan Schwartz, a well-groomed Duke alumnus who rose through the investment-banking division, was named CEO several months ago, when Cayne stepped down. But some wonder whether Spector could have averted the calamity. “If we had someone with his talent and caliber there, you don’t know how this would have gone,” one Bear vice-president said. “He had a very good handle on where all our exposures were.”

Behind the frustration directed at the Fed and Cayne, there is a growing perception at Bear that Schwartz might have done more to fight off the JPMorgan deal. “The firm put itself in a position to be susceptible” to a meltdown, one Bear employee remarked. “We were the smallest of the major firms. In a famine, the skinny guy dies.”

Others wondered why Schwartz, who was attending a conference in Florida, didn’t race back. “When Alan went on CNBC and it came up on the screen that he was in Florida, I thought, ‘That’s weird.’ ” “Why didn’t he come back?” said another staffer. “It’s like the president during a crisis. You need him in the White House.”

Above all, Cayne and Schwartz broke the Wall Street covenant between management and employees. “I’ll accept that you’ll be ridiculously overpaid; just keep the firm going so I can get paid,” a former Bear executive said. “That’s all you have to do. In the most cataclysmic way, they didn’t uphold their end of the bargain.”

On March 19, Dimon received a frosty reception at his first appearance at Bear’s Madison Avenue headquarters. “The meeting was not handled well,” one Bear banker familiar with the exchange said. Some staffers took Dimon’s message to mean, “We’re going to keep the top guys, and screw you if you’re not one of them.”

In the weeks ahead, Dimon and JPMorgan still have to close the deal and persuade Bear’s shareholders to approve the $2-per-share valuation. The contours of a brutal shareholder fight are taking shape. Last Monday, shareholders including British billionaire Joe Lewis, who owns 9 percent of the firm, and Private Capital Management’s Bruce Sherman, with a 4 percent stake, traveled to New York to meet with Bear executives. Schwartz angrily told one shareholder that Bear had been “knifed” and “mugged” by the deal, a sentiment shared by investors. “This is no different than someone putting a gun to your head and saying, ‘Give me your kid,’ ” one insider said.

On March 19, the day Dimon was making the rounds at Bear, Lewis issued a securities filing stating his intention to take “whatever action” was needed to block the JPMorgan acquisition and bring in a competing bidder at a higher price.

Whatever happens, thousands of Bear employees are going to be laid off. On March 20, Bear staffers received severance packages including payouts based on last year’s bonuses. Many aren’t waiting to find out. Staffers are polishing their résumés and working with headhunters to land new jobs. Indeed, even if the shareholders block the deal, it’s unclear what, if anything, will be left of Bear Stearns. “By the time a shareholder vote comes around, there will be nothing there,” one staffer said.

• Jamie Dimon & the Deal of the Century

• A Financial Moron Explains the Crisis