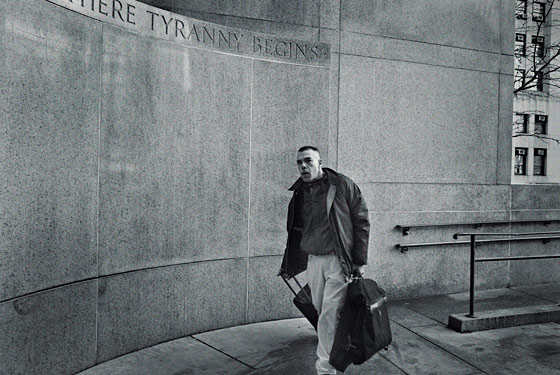

It was a frigid morning last December, and the disheveled man standing before Judge James Gibbons had made his way to the second floor of 100 Centre Street in a thin nylon windbreaker, ill-fitting designer jeans, and a pair of torn jackboots—something out of an old S&M catalogue—which he had accessorized with a wide leather cuff snapped on his wrist. At first he was trembling, as if from the cold. Then the trembling subsided, and his eyelids fell. Dr. Ramon A. “Gabriel” Torres, a near-legendary doctor in the fight against AIDS, had fallen asleep on his feet.

I remembered the first time I had seen him nod off in a crowded room. It was a decade ago, and Torres was the featured speaker at a meeting of top AIDS researchers to discuss a novel way to treat HIV-negative patients who suffered an accidental exposure—a needle stick or broken condom, or a night spent carelessly. At the time, Torres was the director of AIDS programs at St. Vincent’s Medical Center. He was a visionary, responsible for turning a conservative Catholic clinic at the crossroads of the epidemic into a leading research facility, pioneering drug regimens that saved thousands of lives, and bringing AIDS care to homeless New Yorkers, the accomplishment for which he’s best known.

Back then, I supposed that he must have been overcome by exhaustion. Shaken awake by applause, he walked to the microphone in his Armani suit and gave a presentation with all the gravitas befitting his reputation. But he made no sense whatsoever. His words were English, individually well formed. They just didn’t seem to fit together.

When I mentioned this to a friend a day or two later, he said, “Oh, I know. Everybody knows.”

What they knew was that Torres had begun his long romance with drugs. I have since seen him stumbling blurry-eyed and shirtless through the Chelsea night—once I saw him coming out of a notorious West Side drug emporium. There have been reports of drugged encounters in bathhouses, dance clubs, and sex Websites, then arrest after arrest.

Despite numerous trips to rehab, he had squandered his standing among AIDS clinicians and investigators, surrendered admitting privileges, been locked out of his West 23rd Street practice, lost his Chelsea apartment and Miami Beach condo, watched his Fire Island home collapse into foreclosure. He’d accumulated ten criminal charges, some of them felonies stemming from, among other accusations, allegations that he saw patients while his license was temporarily suspended for practicing while high. The first of his trials is scheduled to begin next week. If convicted on all of them, he technically could get as much as 31 years in prison, although somewhere between two and seven years is much more likely.

On the morning he dozed before Judge Gibbons, a simultaneous hearing was taking place in absentia to strip him of his medical license permanently.

“I can’t be in two places at one time,” Torres had whispered to me when he first arrived in court. He showed me a pink slip of paper from the Office of Professional Medical Conduct, then folded it back into his front pocket vacantly. It was the only thing he carried. “I already informed them by phone, fax, and letter that this is going on. But they wouldn’t change the date.”

Torres is one of the untold casualties of the epidemic’s aftershocks. In the decade since AIDS moved from a mostly deadly plague to a largely manageable condition, a surprising number of the frontline veterans of the most difficult years in the fight against the disease have seemed to lose their bearings. Many health-care professionals talk today of feelings of emptiness and disillusionment in the wake of the epidemic’s taming. Some have moved out of the field altogether. For others, drug addiction replaced drug research. Dr. Scott Hitt, the chairman of Bill Clinton’s AIDS advisory commission who died of cancer in November, was stripped of his license for drug possession and admitted to inappropriate contact with two patients. A few years earlier, Jeffrey Wallach, a city clinician with a huge AIDS practice, died of an apparent overdose after years of abusing steroids and other drugs. “I could probably name 50 other docs off the top of my head who were not as well known but were certainly as much on the front lines who have had all different kinds of issues and problems,” says Ken Fornataro, the executive director of AIDS Treatment Data Network, “and that’s just in New York.”

There is no way to know statistically if these stories are more prevalent among AIDS doctors than, say, oncologists. The playwright and activist Larry Kramer, for one, is critical of suggestions that AIDS pioneers have misbehaved disproportionately. But he admits he has heard anecdotes of doctors who made superhuman contributions during the darkest years of AIDS only to fall apart after 1996. “What do they do between 1985 and 1996?” Kramer says. “Huh? That’s eleven years—eleven fucking years. If you’re a doctor in the midst of all of that, and you’ve got hundreds of patients, and every one of them is facing death and is terrified, of course you’re going to crack up. You wouldn’t be a human being if you didn’t.”

Spencer Cox, an ACT UP veteran who founded a think tank called the Medius Institute for Gay Men’s Health, suggests that anybody who lived through the worst of the AIDS crisis has lasting trauma and tends to suffer elevated levels of drug problems, starting later in life. “These aren’t people who were ticking time bombs to begin with and then skidded off the road. They’re our best and brightest. I can’t tell you how many terrific, smart, hardworking, amazing people I know hit middle age and just lost it,” he says.

As Torres stood sleeping before Judge Gibbons, court clerks thumbed through paperwork frantically. Finally, the judge spoke, and Torres lifted his head. “I see there is an open bench warrant,” Judge Gibbons said finally. It turned out Torres had missed a court date on unrelated charges, one involving an alleged assault on a neighbor in his old Chelsea apartment and another alleging drug possession. Unbeknownst to him, a warrant for his arrest had been issued in October.

His attorney, Barry Agulnick, protested to the judge. “He believed that that case had been dismissed. Why would he skip?”

“The problem could be,” Gibbons interrupted, “that due to a drug habit, he’s amassing cases so fast he cannot keep track of them.”

He ordered Torres—“or Dr. Torres, if you indeed are a doctor”—held on $5,000 bail. It was a sum that Torres couldn’t produce. So he was handcuffed and led to the Tombs, where he would spend the next week.

“He’s hit the bottom,” said Agulnick. “Some guys catch a break every once in a while. With Torres, it’s never.”

The next week, Agulnick quit the case; he hadn’t been paid in months.

AIDS wasn’t yet on the horizon when Gabriel Torres set his sights on medicine. The oldest son of a sugarcane farmhand from Ponce, in southern Puerto Rico, Torres was lured to NYU in 1976 with a large financial-aid package to become the first member of his family to earn a degree. He went to Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons as a National Health Service Corps scholar, which requires young doctors to spend a number of years working with underserved populations in exchange for full tuition. Diabetes and nephrology were in his plans, not infectious diseases.

That changed in 1983, the year he arrived at St. Vincent’s to participate in a training rotation. As a gay man, he’d heard about the new scourge. But he was too deep in his books to notice the burgeoning human toll. By that point, over 1,000 people had died of what would come to be called AIDS, yet it was still possible to live in New York and be unaware that the city was the new pandemic’s epicenter.

Torres’s eyes were opened when he entered the intensive-care unit on one of his first rounds. Young gay men occupied eight of the nine beds. Breathing tubes animated their lungs, which were wracked by Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, a previously rare affliction that the Centers for Disease Control was monitoring as part of a mysterious new outbreak. Kneeling next to one of the beds, the frantic mother of a comatose Venezuelan patient was screaming at the boyfriend she’d just learned her son had, while banging her forehead against the floor.

Throughout the hospital were other signs of the coming plague. The emergency room swelled with patients for whom there were no treatments, Torres said, with opportunistic infections so rare they didn’t appear in modern textbooks. “All around the hospital,” Torres says, “you saw Kaposi’s sarcoma and vascular dermatosis, a growth that turns your skin violaceous—it looks like you have grapes growing out of your skin, pendulous grapes; I mean your body is covered entirely with it.”

One man came in with a strange complaint: He looked and felt perfectly healthy, except that his ears were filled with the sound of a helicopter rotor—a symptom, it turned out, of AIDS-related cryptococcal meningitis, which produced intense pressure on his spinal fluids. “We thought he was malingering, but he was dead in a week,” he says. “I still remember his name.”

At the time, some city hospitals were refusing AIDS patients, shipping them instead to larger teaching facilities. Those that did accept patients often embraced draconian isolation policies. Back then I was working at the New York Native, the city’s gay newspaper, fielding calls from people stranded in hospital rooms where no doctors visited them and food trays were left outside the door—patients who were too weak to leave their own beds were sometimes left in their own waste. No hospital received more bitter complaints for more years than St. Vincent’s. “It was so completely insulting that this was happening in the Village, in the epicenter of gay life and the epidemic,” says Jim Hubbard, the co-founder of the ACT UP Oral History Project. “People would stream out of the ACT UP meeting and go and demonstrate at the hospital right then, because it was so awful.”

In this environment, it was also rare for medical students to set their sights on AIDS. Most doctors were terrified about contamination. Dr. Anthony Fauci, today the nation’s highest AIDS official, darkly speculated that transmission might occur otherwise than through bodily fluids. As a result, some doctors wrapped themselves in spacesuitlike protective gear for examining AIDS patients. Others refused to give medical attention altogether. A 1987 survey of doctors in training at New York City hospitals found that a quarter believed it was ethically acceptable to refuse treatment to an AIDS patient. It didn’t get much better over the next few years. As recently as 1990, when a million Americans were living with the virus and 100,000 were already dead, half of all general practitioners said they wouldn’t treat people suffering from the disease, given the chance.

That left the job to a small group of extremely young doctors, mostly women and social-justice types or gay men and lesbians. Says Ronald Bayer, a Columbia professor of public health who has compiled an oral history of AIDS physicians, AIDS Doctors: Voices From the Epidemic, “Here was a moment when only the avant-garde did AIDS, and they were excoriated by their colleagues.”

Among them, an “atmosphere of cowboy medicine” developed, Dr. Abigail Zuger, at the time a resident at Bellevue, said in Bayer’s book. Dr. Joseph Sonnabend—one of the most influential experts on the epidemic, co-founder of the groups that became amfar and the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America as well as a number of other national organizations—personally smuggled pharmaceuticals through Customs that the FDA had banned. “I can’t even begin to tell you what it was like,” he says. “The unbelievable was normal—it’s hard to conceive. It was like a state of siege, there was that sort of energy and hysteria.”

Torres fulfilled his obligations to the National Health Service Corps by taking a posting at the Wards Island Men’s Shelter, which St. Vincent’s ran under contract to the city. While there, the young doctor published studies in prestigious medical journals, mainly focusing on AIDS among marginalized New Yorkers. He conducted the nation’s first HIV-prevalence survey among homeless men, for instance, revealing the startling fact that 62 percent carried the virus—an early indicator that AIDS had jumped the boundaries of the gay community. Partly on the basis of that study, which made headlines in the New York Times in 1989, he was offered the top AIDS job at St. Vincent’s in 1990.

In truth, he had no competition. “Nobody wanted the job,” Torres tells me. At the time, the hospital’s AIDS office was in a storage room on the ground floor of the O’Toole Building, across Seventh Avenue from the hospital, according to Mike Barr, then a staff member. By all accounts, Torres attacked the challenge with unequaled imagination. St. Vincent’s had never been a significant research hospital, but Torres quickly saw a different way to develop the clinic. He began enrolling his patients in cutting-edge pharmaceutical trials, which not only gained them access to promising treatments but also produced an independent income stream for his clinic, at a time when drug companies were paying a lot for access to patients.

At its peak, the clinic had 40 studies running, worth perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars a year. “We had so much money that, quite frankly, it was hard to spend it fast enough,” says Mary Catherine George, the research administrator at the clinic. But spend it they did. The staff grew to include twenty nurse practitioners and fourteen full-time physicians, including psychiatrists and oncologists. They were investigating everything from ways to keep patients from getting pneumonias to the efficacy of the so-called D-drugs, ddI and ddC. St. Vincent’s joined vaccine trials, drug-“cocktail” trials, and studies of salvage therapies for people with multiple drug resistance. Torres became one of the world’s experts on the ways HIV medications alter body shapes of patients and the dual problems of HIV and TB infections, especially among transsexuals and the homeless, who remained his passion.

In fact, it was his work among New York’s most-forgotten communities that set Torres apart from other AIDS doctors. He forged outreach programs to illegal immigrants, intravenous-drug users, transgender patients, and even male prostitutes. This often put him at odds with hospital directors and the Archdiocese. Noel George, who was Torres’s senior research nurse for many of those years, says, “The hospital kept blocking research because they didn’t want condoms mentioned in the consent form.” When Torres wanted to conduct a study of treating people after inadvertent exposures, the hospital refused, arguing that it seemed to be promoting unsafe sex. “I was pushing the envelope,” Torres admits. “They were very uncomfortable about some of the things we were doing.”

But he was given unusual leeway because AIDS, thanks to New York State reimbursement levels, was exceedingly profitable for St. Vincent’s. On peak days, AIDS patients filled 120 beds, more than a third of the hospital’s overall capacity, with even more waiting in the hallways, according to Torres. “There was just mayhem. Gurneys everywhere, people with IVs in chairs, IVs running out of fluid. A nursing shortage. I mean those days were absolute craziness.”

There also was a staggering amount of suffering and death. Despite their efforts, every year close to a third of St. Vincent’s AIDS patients passed away.

Instead of being disheartened, Torres sacrificed everything for the clinic and his patients. Increasingly in demand as a public speaker, he folded his honoraria back into the operating budget. He hardly took vacations, or even a weekend away. “It was more stressful to try to go away than to stay and work,” he tells me. “Not only did I have a lot of patients in the hospital, but a lot of them were my friends. I couldn’t leave them.”

Torres’s ingenuity and passion for the work made him a kind of cult figure. I attended a medical conference once where he stirred up an ovation just by walking into the room. A small number of top AIDS doctors enjoyed similar acclaim. Paul Volberding, who directed the San Francisco General AIDS clinic and is a global leader in AIDS research and care, keeps a letter that reached his office mailbox from England though it was addressed simply to “Dr. Paul, San Francisco.”

“Of course these people got lost—I almost got lost,” says Rodger McFarlane, the first executive director of GMHC. “Nobody talks about it, but it was the most fun I ever had in my life. It’s like wartime.”

But even among his peers, Torres stood out. “There was no bigger star,” says Dr. Victoria Sharp, director of AIDS programs at St. Luke’s–Roosevelt. “The thing about Gabe was, he went to Columbia. He published. He was gorgeous—drop-dead gorgeous. And he was so humble. I mean, there was nothing missing.”

Or so it seemed.

Until the mid-nineties, Torres was as sober as one of the nuns who float through the halls at St. Vincent’s. He says he still doesn’t drink; wine gives him a headache. He claims to have smoked exactly two joints in his life, and has no desire to try again. But in 1994 or 1995, one of his friends offered him Special K, or ketamine, a horse tranquilizer then popular as a club drug. He experimented with it for a while. It was, Torres says, the perfect drug for a hopeless epidemic. “You just wanted to deaden yourself,” he says. “K anesthetizes the pain.” But the minute he felt the drug impeding his life, he declared it off-limits. Besides, there was much to celebrate all of a sudden. Beginning in 1996, new drug regimens Torres helped bring about abruptly changed the course of AIDS, ushering in the first good news in the fifteen-year epidemic. Almost overnight, people grew healthier and the daily inpatient population at St. Vincent’s dropped from 120 to 70, then 40, then fewer.

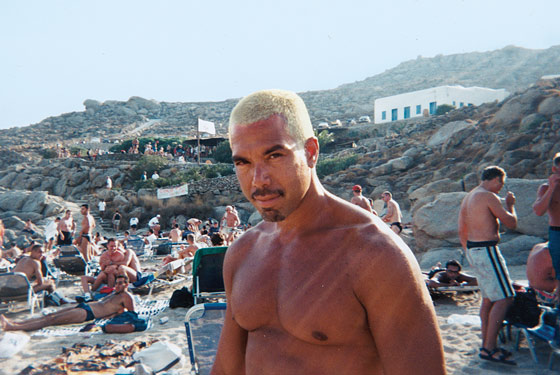

Soon, friends say, Torres was turning to crystal. It was a time when the drug—methamphetamine, long popular as working-class speed, with a following in rural America —was beginning to claim a foothold among urban gay men. Most weren’t reckless kids. “The biggest meth demographic is gay men who survived AIDS and are now in their forties,” says Peter Staley, an HIV-positive recovering addict. “I’ve always called it the perfect midlife-crisis drug.” Berkeley, California–based psychotherapist Walt Odets calls meth use an understandable reaction to the severe and repeated losses from the worst plague years. “This didn’t have some kind of clean ending,” he says. “I read a quote from Mike Nichols, the director, who said once, ‘That’s all blood under the bridge.’ That’s what AIDS is like.”

The drug quickly had Torres in a bind. “He was going through several thousand dollars a week on meth,” according to Darren Allumier, who was Torres’s boyfriend for ten years. “He’s always had this amazing ability to—what’s it called?—hold his liquor and drugs and still function normally. But at home, he was the complete opposite.” Allumier narrates a behind-the-scenes fall into addiction marked by sleeplessness, violence, and repeat calls to 911. It first came to a head one Friday afternoon when the two were leaving for Fire Island. The trip seemed to cause Torres great anxiety, stirring up insecurities about his impact as a doctor. He began to berate himself. “He took a fistful of keys and began pounding himself on the head and neck and back until he was all bloody,” Allumier says. According to both men, violence between them escalated over the following months, culminating in a final breakup in the spring of 1998, followed by endless ad hominems and, briefly, a charge of attempted murder.

“The foundation under him crumbled” is how Allumier sees Torres’s drug use. But Torres spins it in a more positive light. “I always say the crystal was for celebration, not to take care of my pain or whatever,” he says. “I was celebrating the fact that now everyone was living and not dying. It seemed like a reason to celebrate, and crystal was a perfect drug for that. You’ve got all this energy. You stay up. You dance.” He adds, “You wanted to feel alive.”

Simultaneously, the horizon for his AIDS clinic began to look bleak. Fewer admissions meant he was no longer the hospital’s rainmaker. And for a long time after the protease revolution, few new drugs entered into research. “Suddenly, we had no grant money, no research to pursue,” says Mary Catherine George. “We went off a cliff.”

The hospital administration began dismantling Torres’s program, relocating his physicians to other departments and putting the operation on a shorter financial leash. Similar constrictions were happening in other hospitals. But for Torres, it was a destabilizing blow. “I felt totally defeated,” he says. “It was tearing me apart.”

He responded with more “celebrations.” “It became the only way of escaping all this craziness,” he says. An acquaintance—a physician’s assistant who specializes in AIDS—watched mutely as Torres slid from losing his presentation materials at a medical conference, to appearing wasted at a gay bathhouse, to wearing sunglasses in his own office, rocking like a junkie. “I’ve been in recovery now for eighteen years,” says the acquaintance. “I would see doctors and other health-care providers who I knew at some gay event like the Black Party. They’d all be higher than God. There was part of me that in one respect was almost envious. I would say to my husband, how can these guys do it? How can they do drugs and still have a successful practice? And then, of course, they didn’t. It eventually caught up.”

“I was celebrating the fact that now everyone was living and not dying,” says Torres. “Crystal was a perfect drug for that. You’ve got all this energy. You stay up. You dance. You wanted to feel alive.”

Many leading AIDS physicians acknowledge the trend among some doctors, which they consider understandable, given the circumstances. “If what happened to Gabriel is one response, there are of course many who responded in other ways,” says Sonnabend, who today is retired in London and, by his own assessment, mostly broke and lonely but untouched by addiction, though he has buried all but one of his ex-lovers and most of his friends. “How can I be unaffected by all of that? How the hell can I be? How is it possible? I’ve been quite hurt.” Dr. Donna Futterman, a veteran expert in adolescent AIDS at Montefiore Hospital, agrees. “If I was a gay man instead of a gay woman back then,” she says, “I would have been dead in five years.”

Doctors were not the only surprise casualties of the protease era. Many heads of AIDS groups and activists have tumbled into addiction, disillusionment, career crisis, or worse. After years of vigilance, many have recently contracted HIV, says the Medius Institute’s Cox. “Having worked in HIV seems to be a risk for recent HIV infection,” he says.

“Of course these people got lost—I almost got lost,” says Rodger McFarlane, the first executive director of GMHC (at age 26), who went on to found and run some of the city’s leading AIDS agencies. “Nobody talks about it, but it was the most fun I ever had in my life. I never got out of bed with so much energy and so sure of what I needed to do and surrounded by the coolest people, who became respected in our fields. It’s like wartime. When are the relationships so immediate, when are the stakes so high? When do you see the impact you as an individual can have and see radical change made? I mean, it was horrible. It was outrageous. And it seemed to take years. But look what we did! It’s historic shit. You don’t have that crack again. You bet these people got lost when they’re not that person anymore. I’m not talking about ego. You’re the hot shit in the biggest disease, and then treatment becomes available, and then what? Now you go to clinic every day and write prescriptions?”

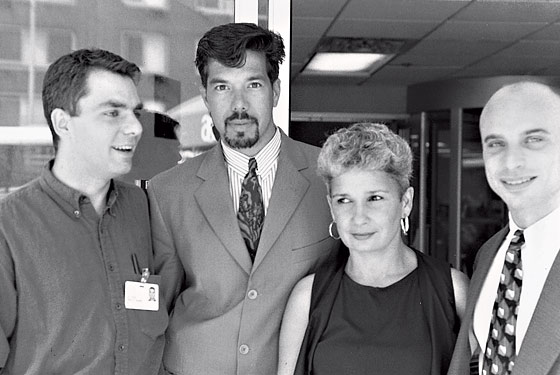

In early 1998, at the suggestion of his colleague Dr. David Ho of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, Torres agreed to meet with a wealthy entrepreneur named Bernie Salick, who planned to finance a flashy, holistic AIDS center on Irving Place, in a facility designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates. Salick offered him a star’s position there, more than doubling his salary to over $350,000—an enormous sum for someone who grew up as poor as Torres had.

The first thing Torres did after he took the job was buy a house in the Pines, and an apartment in Miami Beach—in cash. Every Friday during that first winter, he flew to Florida to party with a new group of friends, a life he’d never even dreamed of attaining. “I was making more money than I’d ever made and spending more than I’d ever spent,” he says. He almost never made it back to work by Monday morning. He sometimes missed Tuesday as well. “He would call me and say, ‘I’m in the tunnel,’ ” remembers Mary Catherine George, who followed Torres to the Salick facility. “I’d say, ‘Well, get the hell out of the tunnel and get into this office. There are patients waiting for you since yesterday.’ ”

In the middle of this slide, Torres’s mother lost her long battle with cancer in 2000. Her death sent him into a Niagara of grief, his friends say. “I was flatlines,” Torres agrees, crying intensely years later. “I was emotionally dead. I didn’t have aspirations to do much of anything.”

Thereafter, people all over the city began to notice that he was falling apart. At a GMHC dinner at the Waldorf featuring Lainie Kazan, according to a witness, his head fell comically into his dinner plate before friends dragged him outside. Eventually, the rumors got so bad that Brian Saltzman, one of his partners, confronted his friend. “I said, ‘I don’t know what’s going on. I haven’t seen you impaired, but there are these allegations. If there is anything going on, I suggest you call the OPMC,’ ” Saltzman remembers, referring to the Office of Professional Medical Conduct. “He absolutely denied there was any problem.”

In an unrelated twist, the posh private practice was going bust anyway. A third partner, Todd Yancey, had been accused of inappropriate sexual contact with a few patients, one of whom committed suicide—he reportedly left a long note blaming Yancey for his depression. The family threatened legal action. Yancey agreed to retire his license, acknowledging he could not defend himself against the charges, and Bernard Salick shuttered the practice soon thereafter.

Next, both Saltzman and Torres headed to Beth Israel. But Torres’s downward spiral continued. One lunch break, he fell asleep in his car—for three hours—and missed a string of appointments, resulting in a suspension for suspected drug use (he takes issue with this characterization, saying that his “somnolence” was owed to “overusing Benadryl” and that he hadn’t used crystal for several days before the incident). Following evaluation at Marworth, a Pennsylvania rehab facility, he was allowed to return on the condition that he submit to random urine tests, but he tested positive five weeks later. He remained on medical leave from the hospital until he resigned on October 11, 2001.

He didn’t quit using, though. Instead, he applied for a number of jobs, including at St. Luke’s–Roosevelt with his old friend Dr. Victoria Sharp. She recalls the day he showed up for an interview. “My secretary said, ‘My God, this guy looks like he’s on drugs.’ He looked terrible.” After receiving him in her office, Sharp expressed concern without mincing words. He rebuffed her. “Quite frankly,” he tells me, “I didn’t think it was any of her business.” She later called a meeting of other top AIDS experts at the bar at the Carlyle to discuss an intervention, but nothing seems to have been done. Later, Torres was offered the job of medical director at Housing Works, the agency for homeless New Yorkers with HIV. At the time, I was on the board of directors. In a bitter fight with the co-founder, Keith Cylar, I argued against putting Torres in a position where lives depended upon him unless he was demonstrably rehabilitated. The offer was rescinded.

Finding himself unemployable, Torres set himself up in private practice in Chelsea, putting a drug-using administrator in charge of running the office and a transgender woman at the front desk. He never brought in enough money to make payroll. “I was able to keep it going by refinancing my Fire Island house every six months or so,” he says.

But there was still further to fall. In early 2004, Torres took himself to Miami for a circuit party, a big event on the gay social calendar. As he boarded his return flight the following Monday morning, agents found a crystal pipe in the pocket of his bomber jacket. “It belonged to this trick I picked up,” he told a friend. “It wasn’t even mine.” They threw him in jail until he could post bail. He was to return in a few months for a court appearance but missed the date by two days. “That’s Gabriel,” says his closest friend, Paul Shelby, a massage therapist. “If there’s a plane to catch, he’s going to miss it.”

When he finally appeared, the judge angrily dispatched him to a court-ordered residential rehab program for three months, leaving his patients stranded.

Meanwhile, back in New York, his office manager—an Israeli citizen named Joseph Kassous—apparently cleared out his personal and corporate checking accounts; siphoned $400,000 more from Torres’s good friend and patient, Baroness Rocio Urquijo of Spain; sold or gave away scores of forged Percocet prescriptions; and jumped bail after the police caught up with him (he’s still at large and believed to be in Mexico). Besides bankrupting Torres, the events touched off an investigation by the attorney general’s office into his prescribing patterns. “My name was found on bottles in all sorts of people’s houses—drug dealers, people who were arrested—all forged,” Torres says. “They came down on me like an earthquake after Joseph.”

“It was like something out of Les Miz,” says Barry Agulnick, who represented him in the investigation. “There is one particular investigator who has been after him for years.”

Ultimately, the investigation came to a close without charges against Torres, but not before the Office of Professional Medical Conduct opened its own probe. More than a year ago, it alleged that he had practiced medicine while intoxicated. It also alleged that he had misrepresented his history of administrative punishments on job applications, a serious violation of ethical code. Beginning on December 21, 2006, his license was suspended for at least twelve months.

Subsequently, he lost his Chelsea rental apartment following a protracted dispute with his landlord, neighbors, and city officials over his dogs (he was raising litters of boxer puppies in his tiny studio, where the floor was piled with feces). Last May, following a physical altercation with a neighbor over the matter, he was arrested and charged with third-degree assault. When he was frisked, police allegedly found a bag filled with powder. “It’s crystal meth, my friend, give it to me,” Torres reportedly demanded. Those charges are still outstanding.

Finally, last August, he was arrested in his office for practicing medicine while on suspension, a charge that involves multiple felonies, including grand larceny. Detectives searching his pockets say they found another envelope of crystal. He has entered not-guilty pleas on all counts, according to Darius Wadia, his new court-appointed attorney.

The total collapse of Gabriel Torres’s life and career has distressed the few people in the AIDS Establishment aware of his plight. “It’s just one of the biggest tragedies I’ve ever seen. This is a guy who had absolutely everything going for him,” says John Grimaldi, a psychiatrist who worked for Torres at St. Vincent’s and is now in practice in Memphis. “All of his colleagues are completely and totally heartbroken about this.”

Jonathan Tobin, who undertook important AIDS research with Torres as head of New York’s Clinical Directors Network, agrees. “Many people are alive because of him,” he says, “and many others died with a greater sense of peace and dignity because of him. I hope in his time of suffering people will come to his assistance with the same selflessness.”

The problem is, nobody knows how to help, or even how to reach him. “I would do anything I could to help him,” says Sharp. “I just don’t know what to do.”

Last fall, as his case percolated through the courts, Torres kept a low profile at his Fire Island home, which he had been trying to sell in order to stave off foreclosure. He lived there on and off, despite having no electricity or insulation, until mid-January, when a cold snap exploded twenty pipes throughout the house. (It has since sold for less than he owed.) He returned to New York with his remaining dog, a boxer named Usmail, a reference to the Puerto Rican fairy tale in which a postage stamp is misread as a proper name. To support himself, Torres was selling his sizable art collection a piece at a time over Craigslist; he has also sold his bed, among other furniture. Finally, he had to give up the dog to an agency for adoption.

Torres at first bunked in with his current boyfriend at an SRO in Times Square, until guards there blacklisted him. With no options left, he went to a city agency, which found him a strict SRO on the Upper West Side—through a program geared for homeless people with HIV.

It seems Torres had fallen victim to the virus in more ways than one. He has been HIV-positive since 2002.

“I was infected by my last boyfriend—it was conscious,” he explained to me awkwardly during a lengthy interview right before Christmas. “Well, not conscious. He was positive and I was negative and we were having unsafe sex.” Was that because he was high on crystal at the time? I wondered. “We were both sober,” he replied. “There is no one reason for every infection.”

“What was the unsafe sex about, then?”

He answered uncertainly. “Love?”

When I saw him a few weeks later, Torres came to my apartment dressed in a fine but faded leather fetish jacket adorned with tight lacework and scores of silver grommets. His eyes looked clearer, and he spoke more lucidly about his situation than he had previously. It had been some time since he last did drugs—either several months, as he said, or several weeks, as seemed more accurate.

And he had a little money in his pocket. He had sold his computer, which allowed him to buy belated Christmas presents for his sister’s children in New Jersey. The visit had put him in an upbeat mood. He had hope for his new lawyer and faith that he’ll get probation, not jail time.

“I’m functional,” he said proudly. But then he darkened. “I feel worse about the people I cared for. I feel that I’ve abandoned them.”