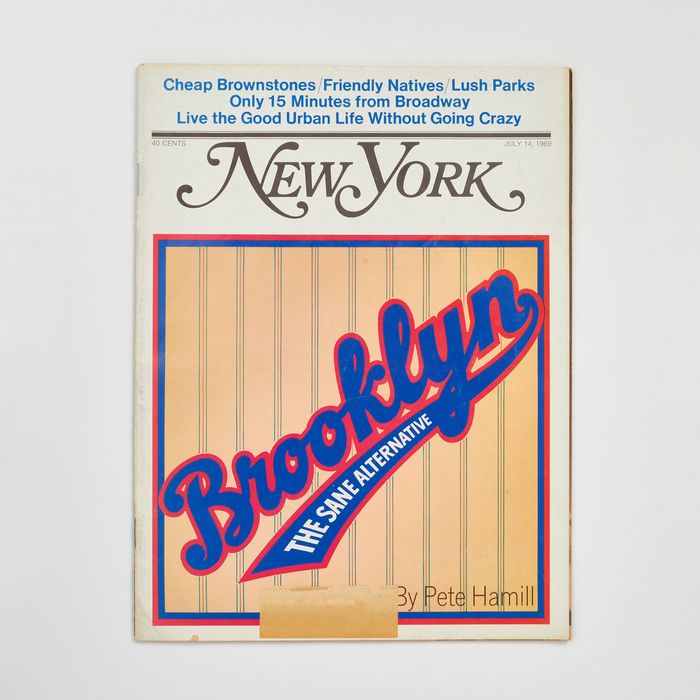

From the July 14, 1969 issue of New York Magazine.

One cold spring I found myself alone in Rome, in a small room high up over Parioli, trying to write. The words came thickly, sluggishly, and none of them were any good. I quit for the day. For a while I read day-old copies of Paese Sera, the Communist daily, and the Paris Herald, and then, bored, I turned on the radio, lay down on the lumpy couch, and, half-listening, stared out at the empty sky. The music was the usual raucous Italian stew, mixed with screaming commercials, and I fell into a heavy doze. Then, suddenly, absurdly, I came awake, as an old song started to play. She kicked out my windshield. She hit me over the head. She cussed and cried. And said I’d lied. And wished that I was dead. Oh! Lay that pistol down, Babe … It was “Pistol Packin’ Mama,” by Tex Ritter, and how it came to be played that afternoon, 20 years after Anzio, I’ll never know. But I did not think about the hard young men of that old beachhead, or about their war, or even about cowboys in flight from homicidal girlfriends. I thought about Brooklyn.

When I was a kid growing up in Brooklyn, “Pistol Pack-in’ Mama” was the first record we ever owned. My brother Tommy and I bought it for a dime in a secondhand book-and-record shop on Pearl Street under the Myrtle Avenue E1, and we played it until the grooves were gone. The week before we bought it, my mother had arrived home with an old wine-colored hand-cranked Victrola, complete with picture of faithful dog and master’s voice, and a packet of nail-like needles. It was given the place of honor in the living room, in the old top-floor right at 378 Seventh Avenue; that is, it was placed on top of the kerosene stove for the duration of the summer, and it was almost as heavy as the five-gallon drums we hauled home in the winter snow to feed the stove (steam heat, then, was a luxury assigned to the Irish with property). We thought that phonograph was a bloody marvel.

The purchase of “Pistol Packin’ Mama” was something else again. We did not really lust after hymns of violence; we weren’t country-and-western buffs (we always preferred Charles Starrett, the Durango Kid, who was all business, to the saps like Roy Rogers and Gene Autry, who played banjo as they rode after outlaws). It was something more complicated. We bought “Pistol Packin’ Mama” because it was the first hard, solid evidence we had until then about the existence of the world outside Brooklyn.

We studied geography in school, of course, with all those roll-down maps of the world, those dull figures about copra production, the uses of sisal and, of course, the location of the Holy Land. But Brooklyn was not on those maps. New York was, but to us, New York was some strange, exotic city across the river, where there were people who rooted for the Giants and the Yankees. Brooklyn was not there. Even Battle Creek, Michigan, where we sent a hundred Kellogg boxtops, was on the map. Brooklyn was not. The people who secretly ruled the earth did not recognize us, and we did not really recognize them. So to own a copy of that awful record was like establishing diplomatic relations with the rest of the world; “Pistol Packin’ Mama” had been a hit—broadcast from a million radios—and for Tommy and me to have a copy of it, to hold it in our hands, to turn it over (the flip side was something that went “Rosalita, you are the rose of the baaaanjo!”), to be able to play it at our leisure and not wait to hear it at the whim of those people who secretly ruled the earth—that was breaking out.

Lying on that couch in Rome, I had already learned that you never break out of anything, that it was ludicrous to think that you could solve anything by setting out on journeys. The last time I had gone there, Brooklyn had seemed shabby and worn-out: not just in the neighborhood where I grew up, but everywhere. There was something special, almost private, about being from Brooklyn when I was growing up: a sense of community, a sense of being home. But I hadn’t lived there for a long time, and when I did go it seemed always for a disaster: to see the corpses of men, baked by the heat, being carried out of the Constellation as it burned in the snow at the Navy Yard; to visit, like a ghoul, the mothers of dead soldiers; to cover the latest hostilities between the Gallo and Profaci mobs; to talk with the father of an eight-year-old boy who had pushed a girl off a roof in Williamsburg. Only the dead know Brooklyn, Thomas Wolfe had written. For a while it seemed that way. The place had come unraveled, like the spring of a clock dropped from a high floor. Nevertheless, that night in Rome I started getting ready to go home.

The Brooklyn I came home to has changed. For the first time in 10 years, it seems to have come together. In Park Slope, people like David Levine, Jeremy Larner, Joe Flaherty, Sol Yurick have moved into the splendid old brownstones; the streets seem a bit cleaner; on some streets, citizens are actually planting trees again, with money they have raised themselves through block associations and block parties. Art galleries are opening. Neighborhoods like Bay Ridge and South Brooklyn now have boutiques and head shops. People who have been driven out of the Village and Brooklyn Heights by the greed of real-estate operators are learning that it is not yet necessary to decamp for Red Bank or Garden City. It is still possible in Park Slope, for example, to rent a duplex with a garden for $200 a month, a half-block from the subway; still possible to buy a brownstone in reasonably good condition for $30,000, with a number of fairly good houses available for less, if you are willing to invest in reconditioning them. Hundreds of people are discovering that Brooklyn has become the Sane Alternative: a part of New York where you can live a decent urban life without going broke, where you can educate your children without having the income of an Onassis, a place where it is still possible to see the sky, and all of it only 15 minutes from Wall Street. The Sane Alternative is Brooklyn.

Impressions can be backed up by any number of statistics. Today, Brooklyn is the fourth-largest city in the United States. It has more people than 26 states, contains one out of every 65 people born in this country. For 30 years there have been jokes about the tree that grew in Brooklyn; in fact, the borough contains 235,000 trees, which is a hell of a lot more than you will find in the high-rise ghettos of the Upper East Side. Brooklyn’s purchasing power in 1968 rose to $6,600,000,000, up $347,000,000 over the previous year. In 1967, wholesale and retail trade in the borough amounted to $5,400,000,000; there was a payroll of $2,400,000,000 for 704,800 jobholders. In a study called “The Next Twenty Years,” the New York Port Authority predicts a 7.7 per cent growth in jobs by 1985, while population will grow at only 2 per cent. According to a 1965 Dun and Bradstreet report, Brooklyn is now the nation’s fourth-largest industrial county, third-largest food consumer, and fourth-largest user of goods and services. The median income ($5,816) is still $175 less than that in Manhattan; but the median age of the 2,627,420 citizens is 33.5, lower than New York City’s as a whole (35) and lower than the median (34) in the metropolitan region that includes Westchester, Rockland, Nassau and Suffolk Counties.

But no set of statistics can adequately explain what has happened to Brooklyn in the years since the end of the Second World War. They don’t explain its decline. They don’t explain its renaissance.

For me, Brooklyn is the great proof of the theory that many of the problems of the American city are emotional. If you were born in Brooklyn, as I was, you learned something about this quite early. Through most of its early history, Brooklyn was really a kind of bucolic suburb, dedicated to middle-class values, solid and phlegmatic. Its citizens owned small farms. They opened small manufacturing plants, especially on the Manhattan side of Prospect Park, which is the section of Brooklyn that today most resembles the dark industrial image of the 19th century. When the subways pushed out past Prospect Park into Flatbush and beyond, Brooklyn became the bedroom for the middle class. Its first period of shock and decline came after the 1898 Mistake, when the five boroughs were united into Greater New York under the supposedly benevolent dictatorship of Manhattan. Until then, if we are to believe old newspapers, Brooklynites were proud and industrious citizens who planted their own trees, who gloried in their independence. Most of them opposed the 1898 Mistake; but the deal was pushed through the State Legislature by the Republicans, who thought that the large number of Republicans in Brooklyn would help them wrest control of the entire city from Tammany Hall. (In those days, of course, Republicans were in the tradition of Lincoln, not Goldwater and Thurmond.)

After the 1898 Mistake, some sections of Brooklyn started to change radically. In the 19th-century part of town, the poor Irish and the poor Italians started moving in; they filled the old-law cold-water-flat tenements; they ran speakeasies during Prohibition; some of them learned how to make money with murder. The poor Jews moved into Williamsburg and Brownsville, where they also learned something about the rackets. The respectable people, as they thought of themselves, fled to Flatbush and Bensonhurst and even out into the wilds of Flatlands. But there was a long period of stability that almost lasted through the Second World War.

The first cracks in that stability showed up during the war, when a lot of fathers were away fighting and a lot of mothers were working in war plants. Some Brooklynites had been shocked at the revelation about Murder, Incorporated, the brutal Brooklyn-based Jewish-Italian mob whose members killed for money. But when the teenage gangs started roving Brooklyn during the war, then some citizens thought the end was near (you could abide Murder, Inc., of course, if your other institutions—family, church, jobs—remained stable). In Bedford-Stuyvesant, the first black gangs, the Bishops and the Robins, began to assemble down on Sands Street; the Navy Yard Boys were already rolling sailors and shipyard workers; the Red Hook Boys came out of the first projects and the side streets around the Gowanus Canal; the Garfield Boys, from Garfield Place in South Brooklyn, expanded into the South Brooklyn Boys, and became the training ground for many of the soldiers who are now in the Brooklyn chapters of the Mafia. In my neighborhood, the Shamrock Boys became the Tigers, and they fought the South Brooklyn Boys with an expertise in urban guerrilla warfare (on both sides) that the Black Panthers would be advised to study. I don’t know if there ever really was a gang called the Amboy Dukes (I am told by buffs that there was), but Irving Shulman’s The Amboy Dukes became the bible for a lot of these kids; they studied the sayings of Crazy Shack the way the motorcycle gangs later studied Lee Marvin and Brando in The Wild One.

The gangs were wild, often brutal; there were more than a few knifings and gang rapes, and a number of killings, especially after the war, when veterans started bringing home guns as souvenirs; in shop classes in the high schools, students spent more time making zip guns out of pieces of pipe than they did making bookcases or pieces of sinks. The gun—especially if it was a real gun—became a thing of awe. The first time I ever saw Joe Gallo (they called him Joe the Blond in those days) he was in the Ace Pool Room upstairs from his father’s luncheonette on Church Avenue; someone, I think it was an old friend named Johnny Rose, whispered to me. “Don’t ever say nuthin’ about him: he’s packin’.”

The gangs started breaking up in the ’50s. First, the Korean War took most of the survivors away, all of those kids who had been too young for the Second World War. By the time they came home they were sick of fighting; they married, and some of them moved away. But while they were gone, something else had arrived in Brooklyn: drugs. What the Youth Board and the cops had not been able to do, heroin did. More of them died from O.D.’s than ever died in the gang wars. Prison took a lot of them, and for some odd reason, the ones who had managed to escape arrests and habits became cops. Only two really new gangs started in the ’50s: the Jokers and a gang from my neighborhood which called itself Skid Row. The Jokers lost a lot of members to drugs, and a few of them were involved in a brutal stomp-killing. I still see some of the Skid Row kids around. My brother Tommy was a member for a while; by the time he was in CCNY, three of the gang were already dead from heroin.

The whole terrible period of the gangs, followed by the introduction of heroin, changed a lot of citizens’ attitudes about Brooklyn. Those who had escaped the Lower East Side now started talking about escaping Brooklyn. Events seemed to have moved beyond their control. You could do the best you were capable of doing: work hard, hold two jobs, get bigger and better television sets for the living room, watch steam heat replace kerosene stoves, see the old coal stoves in the kitchens dragged out to be replaced by modern gas ovens, and still people in their teens were found dead in the shrubs of Prospect Park, their arms as scarred as school desks. “We gotta get outa Brooklyn.” You heard it over and over in those days. It wasn’t a matter of moving from one neighborhood to the next; the transportation system was too good for all that; it was out “to the island” or to California or Rockland County. The idea was to get out.

Leaving was made easier by four central factors in the period of postwar decline in Brooklyn. All, in their special ways, were emotional. The four factors: 1) the folding of the Brooklyn Eagle; 2) the departure of the Brooklyn Dodgers for California; 3) the long years of insecurity and the final folding of the Brooklyn Navy Yard; 4) the migration of southern Negroes, most of whom settled in Brooklyn, not Manhattan.

The Eagle was not the greatest newspaper in New York in its day; there were after all, eight others (the Times, Herald Tribune, News, Mirror, World-Telegram, Post, Journal-American, and the Sun) and for years Brooklyn had two other papers—the Citizen and the Times-Union. But the Eagle was a pretty good paper for what it was attempting to do, and all it ever really attempted was to cover Brooklyn. I used to deliver it after school, which is why one shoulder is lower than the other, but along with a lot of other people I used to read it. I don’t have the slightest idea what its editorial policies were, though I imagine they were conservative, since its owner eventually folded it up instead of submitting to the Newspaper Guild. I used to read the comics and the sports pages and odd features like Uncle Ray’s Corner, which was all about the lifestyle of the mongoose, and other matters. The best comic strips were Invisible Scarlet O’Neil, who had some kind of special vein in her arm which she pressed to become invisible, and Steve Roper, which was about a magazine reporter. Of the sportswriters, I only remember Harold C. Burr, who had a gnarled face pasted above his column and looked something like Burt Shotton, who was interim Pope of the Dodgers while Leo Durocher sat out a suspension, and Tommy Holmes, who joined the staff of the Herald Tribune after the Eagle folded.

But even though the Eagle was not a great paper, it had a great function: it helped to weld together an extremely heterogeneous community. Without it, Brooklyn became a vast network of hamlets, whose boundaries were rigidly drawn but whose connections with each other were vague at best, hostile at worst. None of the three surviving metropolitan newspapers really covers Brooklyn now until events—Ocean Hill-Brownsville, for example—have reached the stage of crisis; the New York Times has more people in Asia than it has in Brooklyn, and you could excuse that, certainly, on grounds of priorities if you did not also know that this most powerful New York paper has three columnists writing on national affairs, one writing on European affairs, and none at all writing about this city.

Without the Eagle, local merchants floundered for years in their attempt to reach their old customers; two large Brooklyn department stores—Namm’s and Loeser’s—folded up. If you were looking for an apartment or a furnished room in Brooklyn, there was no central bulletin board. School sports are still largely ignored in the metropolitan papers, as Pete Axthelm pointed out so vividly in these pages a few months ago about the great Boys’ High teams; Boys’ High is in Brooklyn, for God’s sake, in Bedford-Stuyvesant! How could you expect to get your reporter back alive? But the Eagle covered school sports with a vengeance, and the rivalries between various high schools were strong and alive. Today, they don’t seem to matter much; hell, even the old ladies who used to yank the Eagle from my hand to read the obituaries don’t have that consolation anymore.

Nobody really covers the Brooklyn Borough President’s office anymore (as I suppose nobody has covered the Bronx Borough President since the absorption of the Bronx Home News by the Post). Nobody covers the borough as a whole. When Hugh Carey announced that he was running for mayor, not many New Yorkers knew who he was, despite the fact that he is one of the most important members of the New York City Congressional delegation, and comes from the borough with the strongest Democratic party machine. He is from Brooklyn: nobody knows his name. (The void left by the loss of the Eagle has been increasingly filled in recent years by the weekly neighborhood papers, of which the Park Slope News-Home Reporter is by far the best I’ve seen. During the school strike, it ran the single best account of the anger and bitterness on local levels of any paper in the city.) In any other city its size, there would be at least two newspapers. Brooklyn has none.

The loss of the Dodgers was an even deeper emotional shock to the people of Brooklyn, because it affected so many more people than the Eagle’s demise did. Kids, for example. I remember an afternoon in the fall of 1941, when I was 6, sitting in the midst of a crowd of thousands on the steps of the just-opened central branch of the Brooklyn Public Library. A few days before, the Dodgers had won the National League pennant. All through the ’30s, they were the clowns of the league: an outfielder named Babe Herman had been hit on the head with a fly ball; three Dodger runners once ended up on third base at the same time; a player named Casey Stengel once came to bat, tipped his hat, and a bird flew out. But in 1941 they won the pennant, and Brooklyn welcomed them home like champions. All the schools were closed. There was a motorcade from the Brooklyn Borough Hall right up Flatbush Avenue to Ebbets Field, and in the huge crowds people were laughing and cheering and crying, lost in that kind of innocent euphoria that always comes when underdogs win out against all odds. (Imagine what will happen in this town when the Mets finally win a pennant.) All of them were there: Kirby Higbe, Hugh Casey, Dolf Camilli, Durocher himself, Pee Wee Reese, the great and tragic Pete Reiser: all of them smiling and waving in the bright sunshine. I was 6, and even I knew who they were.

Well, they lost the World Series that year to the hated Yankees, when Mickey Owen dropped a third strike. But nobody gave up on them. “Wait till nex’ year” became the perennial battle cry, and for the next 15 years they were one of the finest baseball clubs in the country. Then suddenly, with the stealth of a flat thief, Walter O’Malley took them away. They were still making money at Ebbets Field, despite the old ballpark’s rickety condition and despite television. Dodger fans, after all, were loyal. But the Dodgers, in O’Malley’s opinion, were just not making enough money. One barren spring, Ebbets Field was left empty and dark, the dugouts abandoned, the infield turning to brittle dust, the great greensward of the outfield gone brown and mottled, the bleachers, where so much laughter, joy and sorrow had been staged, whipped by a cold wind. Today the old ballpark is gone. Still another housing project is planted on its site, with only a brass plaque to tip a chiseled hat to a rowdy and innocent past.

The operative word in the whole matter of the Dodgers is innocent. Baseball was a sport then, and if you came from Brooklyn, baseball meant the Dodgers. There were always some nonconformists; I remember a guy named Jackie McEvoy who rooted for the Giants and Buddy Kelly, who later died in Korea, rooting for the Yankees. But the Dodgers really were “The Pride of Brooklyn” and Dixie Walker really was “The People’s Cherce.” This vast confraternity of baseball maniacs held that borough together in a very special way; first, they provided common ground: Italians, Irish, blacks, Jews, Poles, all went to the games. Second, they provided something to talk about that did not involve religion, politics or race. And most importantly, they helped refute the canards about Brooklyn that puzzled so many of us when we were kids: the tree, the Brooklyn accent, the William Bendix type in all the movies, etc.

Dodger fans believed in myths. They were romantics, of course, hoping that the impossible could be made possible, but often they settled for small victories. If the headline on the back page of the Daily News said FLOCK BEAT JINTS 3-2, then all was well with the world. It was no small surprise that when Bobby Thomson hit The Home Run off Ralph Branca to win the 1951 pennant for the Giants, several people in Brooklyn committed suicide.

I suppose that such emotions over a group of grown men playing a boy’s game seem rather ludicrous today. But the people of Brooklyn had this one thing, this one simple belief: that ballplayers were the best people on earth. And in the evenings, thousands of fans, literally, would walk across Prospect Park to the night games, past the Swan Lake and the Zoo and out onto Flatbush Avenue, joined together by this odd faith in people named Snider and Furillo and Campanella and Cox. They were part of an experience larger than themselves, something that involved gray scoreboards, Red Barber, peanuts, special cops, the Brooklyn Sym-Phony, the crowds on the streets outside, Gladys Gooding at the organ, the roar at the crack of the bat, Pete Reiser breaking his skull against the concave outfield wall, Snider dropping home runs into the gas station on Bedford Avenue, black men laughing with white men in the bleachers when Robinson took his jittery lead to second, beer, hot dogs, laughter. Laughter. The Dodgers were called Dem Bums, and the laughter came in part from knowing that they were not.

And when they left, the people of Brooklyn were shocked. As deeply shocked as they had been by almost any other public act in their time. They had given the Dodgers unquestioned loyalty. They had given the Dodgers love. It never mattered to the fans that the Dodgers also made a lot of money. Hell, they should make a lot of money. The important thing was the game, the field of play, the heroes. But O’Malley took them away. For money. Nothing else. Sheer, pure greed. And for a lot of people that was the end of innocence. Romantics are always betrayed in the end, and O’Malley did a savage job of betrayal.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard was crucial to Brooklyn for at least one very good reason: it gave us work. It even gave me work. In 1951, during the Korean War, I went to work at Shop 17 in Building 63 of the Navy Yard as an apprentice sheet-metal worker. The number of men working there had declined from a peak of 70,000 during the Second World War to about 40,000, but the Yard was still the largest single employer in the borough. I hardly know the boy I was then; in memory it was a rough wild time, with a lot of drinking in the saloons of Flushing Avenue, much laughter with welders, and kindness from various people who said I was a bloody fool to be working with my hands when I could still go back and finish high school. I had one great job, with a thin, coughing black man who was a welder-burner and who stopped working every half-hour to drink milk. He said it coated his lungs against the filings of burnt metal. He coughed a lot anyway. We were working on an aircraft carrier named the Wasp, which was being re-fitted to accommodate jet aircraft. All the old bulkheads had to be removed, to be replaced with sturdier walls. His job was to burn around the edges of the bulkheads with an acetylene torch. My job was to pile into the bulkheads with a huge 20-pound hammer and knock them flat. It was an orgy of sheer animal fury, setting yourself, swinging ferociously, beating and smashing those bulkheads until they fell, while the thin black man coughed and laughed. “You some crazy white boy,” he would say.

But all of us working there, even in the early ’50s, knew that the Navy Yard could not make it. To begin with, it was not a very economic place to build ships. It could be used for repair work, of course, but the big jobs—the new carriers, the atomic submarines—almost all went to private industry, or to shipyards where the workers were a little hungrier. In the Navy Yard you were a federal civil servant; it was very tough to get rid of you over small matters. The professionals at the Yard did a good day’s work, but for a lot of the people who saw it as a day’s pay, there wasn’t much work done at all. At Shop 17, they would punch in at 8 a.m. and immediately dash to the men’s room on the second floor. They would then grab an empty stall (not an easy matter), put an arm on the toilet-paper roll, and pass out for an hour. Later, they would go down to the floor, check out to the tool room, and spend an hour smoking. There might be a little work done, but by 11:30 it was back to the men’s room to start washing up for lunch. After lunch, the pattern repeated itself, except that washing up to go home often started at 4 p.m., a full hour before checking out. There was something beautiful about the sheer audacity of those malingerers, but it also spelled the doom of the Yard. The 70,000 dwindled to 10,000 and finally to none. When Robert McNamara finally ordered the Yard closed, there was great public hand-wringing; nobody who ever worked there was at all surprised.

In addition to the loss of immediate jobs, there were other things involved for the people of Brooklyn. Many small factories and businesses lived off the Yard as subcontractors. In the immediate vicinity of the Yard there were bars, gas stations, naval outfitters, whose lives were intimately involved. In the long years of rumor and uncertainty, many gave up and moved on. The workers themselves were wary of signing leases, buying homes, purchasing anything on credit; they simply did not know when the ax would fall. A number of smaller businessmen in Brooklyn felt that if the Navy Yard could not make it, with its natural advantages, its federal subsidy, then they never could make it. The Navy Yard, in the years of its decline, became still another emotional symbol. Brooklyn without the Yard was not Brooklyn. It was as simple as that.

The black migration hit Brooklyn harder than any other part of the city. There were pockets of Puerto Ricans in Brooklyn, clustered around Smith Street in Boerum Hill, around the Williamsburg Bridge, and out in Sunset Park. But the really large numbers of Puerto Ricans had gone to East Harlem and the South Bronx. The southern black man came to Brooklyn.

There were several reasons for this. It was far more difficult for a badly-educated rural black man to get an apartment in Harlem than it was in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Harlem was a society, the black capital of America, with its already well-defined institutions: churches, numbers runners, landlords, restaurants, artists, after-hours places, con men, musicians, etc. Bed-Stuy was much looser, much less structured. In Bed-Stuy you didn’t have to be hip.

Bed-Stuy was also easier to block-bust. A number of black real-estate operators (in addition to whites) made fortunes busting Bed-Stuy. They often employed white salesmen, who would purchase a house in a white street, move in a black family, and then start calling up everyone else on the street. Since many of these areas had two-family houses, or old elegant brownstones, this was much easier to do in Brooklyn than it was in Harlem, where old-law tenements were the rule. Less money was involved, and more heartbreak, especially for the unfortunate hardworking black man who thought he had escaped the ghetto only to find that it was coming out behind him.

So Bedford-Stuyvesant exploded. Whites began leaving by the hundreds. In places like Brownsville, they left because Brownsville had almost always been a slum, and the second generation that was making it did not see any need for further loyalty. Others simply saw the whole thing as hopeless: Brooklyn, which in their youth had been the city of trees and free spaces and security, was being torn apart by drugs and gang wars. The Eagle was gone, the Dodgers had departed: Take the money and get out while you can. There was racial fear involved, of course, but it would be too easy to explain it all away that way. It was race plus despair plus insecurity about money plus desires for the betterment of one’s children plus—the most important plus—the loss of a feeling of community.

As Bedford-Stuyvesant expanded (any street that was occupied by blacks became Bedford-Stuyvesant, whether it was in Clinton Hill or Crown Heights), fear expanded. In Park Slope, across Flatbush Avenue from Bed-Stuy, real-estate operators started breaking up the fine old brownstones into black boarding houses. Most were occupied by transients, as boarding houses have always been occupied, and they simply didn’t care what neighbors thought about them. The streets became littered with broken bottles and discarded beer cans; the yards filled with garbage; drug arrests increased; hookers worked the avenues; there were knifings and shootings, and soon the merchants on Flatbush Avenue started folding up and moving away. No insurance could cover what they stood to lose. When the Peconic Clam Bar on the corner of Flatbush and Bergen Street closed up because of too many stick-ups, the game looked finished. The Peconic Clam Bar was across the street from Brooklyn Police Headquarters.

And then, suddenly, Brooklyn seemed to reverse itself. You still cannot get a taxi to take you from the Village to any neighborhood remotely near Bed-Stuy. But the borough has halted its own decline, stopped, brought the panic and the despair almost to an end.

Again, the reasons are complicated, and have certain emotional roots. The wound of the Dodgers’ departure seems finally healed; the arrival of the Mets gave the old Dodger fans something to cheer for, and there are no more of the old Brooklyn Dodgers now playing for the Los Angeles team. Baseball itself has declined in interest: it’s slow, dull, almost sedate these days, especially on television. Pro football excites more people in the Brooklyn saloons, and it is a measure of the anti-Establishment, anti-Manhattan feelings of Brooklynites that they all seem to root for the Jets (not all, of course, not all, but the romantics do).

Word also began to drift in from the suburbs: things were not all well out there. Those who left Brooklyn because the schools were overcrowded soon found that the schools were also overcrowded in Babylon. Those who fled the terrors of drugs soon found that there were drugs in Rahway and Red Bank and Nyack too, and that flight alone would not avoid that peril. There was cultural shock. A childhood spent leaning against lampposts outside candy stores could not be easily discarded, especially on streets where there were no candy stores, where the bright lights did not shine into the night, where the laughter of the neighborhood saloon was not always available. People started longing for the Old Neighborhood. “These people can’t even make a egg cream right.” “I tried to get a bits-eye-oh out here an’ it tastes like a pair a Keds.” When I would go out to California on various assignments, I learned that I would be serving as a courier from the Real World; guys who had gone out to Costa Mesa and San Jose and L.A. 20 years before wanted me to bring veal, real-thin-honest-to-Jesus veal cutlets so they could make veal Parmigiana the way it is supposed to be made. In the suburbs late at night, people would sit in their living rooms and talk about boxball, devilball, buck-buck-how-many-horns-are-up? (called Johnny Onna Pony by the intellectuals), ringalevio, and always, always, stickball. Remember the time Johnny McAleer hit three spaldeens over the factory roof? Or the time Billy Rossiter swung at a ball, the bat flew out of his hands, hit an old lady on the head, and went through the window on 12th Street? Remember the Arrows, and the great money games they had on 13th and Eighth? Nostalgia worked its sinister charms. The Old Neighborhood wasn’t much, but it wasn’t this empty grub-like existence in the suburbs, struggling with mortgages and crabgrass and PTA meetings and water taxes and neighbors who had never shared one common experience with you. A little at a time, people started to drift back. It was not, and is not, a flood. But it has begun.

For younger people, the suburbs seemed to hold a special horror. If you were a writer, and you were faced with a move to the suburbs, you would rather go all the way into exile: to Mexico or Ireland or Rome. You could not live in the Village or Brooklyn Heights, because the real-estate scoundrels had made those places special preserves for the super-affluent (you could live in those places, of course, but the things you would have to do to afford it would make it impossible to live with yourself). Younger people started looking over the neighboring terrain. They cracked Cobble Hill first, reclaiming a number of fairly good buildings. Then Park Slope started to open up; the boarding houses were bought for as little as $14,000, cleaned out, re-built and re-wired. That was only four and five years ago. Today, the prices are slowly being driven up, and the great fear is that the real-estate people will take over this place too.

The New People, as they are called, saw Brooklyn fresh. They had not known it before, so they knew nothing about its decline. Most important, they carried with them no old emotional wounds. Instead they saw it as a place with great broad boulevards like Eastern Parkway and Ocean Parkway (once, my brother and I walked out Ocean Parkway all the way to Avenue T because we read in the papers that Rocky Graziano lived there; we sat around on benches for hours, but we never saw Rocky, who was the middleweight champion of the world.) They recognized that Greenwood Cemetery, which contains the bones of such diverse worthies as Boss Tweed and William S. Hart, was one of the great urban glades, a spot with lush foliage, sudden hills, bizarre statuary (at night, when we were kids, we would sneak into the cemetery to try to catch the giant turtles which lived in its ponds; the ghosts sent us running). They know that the Brooklyn Museum is one of the finest in the country, with a great collection of graphics, a splendid African collection, some superb American Indian pieces, and paintings by Ryder, Jack Levine, etc. (we went there to see the mummies, to walk into the bowels of the mock pyramid, dreading the Pharaoh’s curse, remembering every terror of that great picture The Mummy’s Hand.) They know that Prospect Park is a masterpiece of landscape architecture, the park that learned from the mistakes of Central Park, which by comparison is bland and flat, and they know that during the Revolutionary War, George Washington had a command post in its hills (but they’ve never been inside Devil’s Cave, nor did they know what happened in the night in the shrubs along the Indian War Path, and they don’t know the spot where Yockomo was shot to death near the Swan Lake by Scappy from South Brooklyn, and they weren’t there the night that Vito Pinto dove into the Big Lake at three in the morning and found himself wedged in the mud three inches below the surface, and they never saw Jimmy Budgell come tearing down the horse path on a strawberry roan like one of the Three Musketeers). They know that the great arch at Grand Army Plaza contains a fine piece of sculpture by Frederick Remington, that there is an abandoned tunnel under the Plaza, that the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library is one of the best in the city (and when I was a kid I used to look up at the carved legend on the wall that begins HERE ARE ENSHRINED THE LONGING OF GREAT HEARTS … and spent one long summer hoping that someday I would be a Great Heart too and that maybe books were the key). They saw Brooklyn in a way that we had not seen it when we were young, and they saw it in a way that Brooklyn had not seen itself, perhaps, since the years before the 1898 Mistake. I just wish that they could have been there that afternoon at the now-shuttered 16th Street Theatre, when Tim Lee (now at the Post) and his brother Mike were taken by their mother for the usual Saturday matinee of three Republic westerns. At one point, a Superman chapter came on, and Mike Lee stood up, and shouted at the top of his lungs: “Hey, Ma! I can see the crack of his ass!” His mother beat him mercilessly with a banana that was part of the lunch, and then took them all home.

The New People are part of the emotional cure. There are other, more practical cures under way. For one thing, the migration of southern blacks seems to have come to an end; it has at least been reduced to a trickle. More importantly, Bedford-Stuyvesant has been developing its own institutions. Quietly and steadily, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, which was started through the efforts of Robert Kennedy, has been working very hard at bringing jobs to the area. IBM has already announced that it will build a manufacturing plant there. Plans are under way to build a new Boys’ High. The city has committed itself to building a community college in the area. Through one of the two corporations set up by Senator Kennedy, a $75,000,000 mortgage loan fund has been put together and a job-training program for 1,200 persons is under way. With federal help, three firms (Advance Hudson Mounting and Finishing Co.: Campus Graphics Inc.; Day Pac Industries Inc.) have begun a $30,000,000 project of plant construction that will employ 1,435 people. Say what you will about the Black Panthers, they probably have a small point to make about ghetto businesses owned by whites: through reform of the insurance laws, more and more black businesses are starting in New York, the vast majority of them in Brooklyn. The development of the Black Pearl taxi system is an example of the building of institutions; let the white cabdrivers bitch and complain and issue dark warnings about cabdrivers in “gypsy” cabs who might have criminal records. The fact is, the Black Pearl cabs (and others not connected with Black Pearl) have made it possible for black residents of Bedford-Stuyvesant to travel the way a lot of other New Yorkers travel, and the money is staying in the area.

In addition, thousands of Puerto Ricans have settled in Brooklyn, in flight from the urban demolition that passes for slum clearance in Manhattan and the Bronx. There are now more Puerto Ricans in Brooklyn than in any of the other five boroughs, and they have brought with them their many virtues: the instinct to open small businesses, the almost visceral need to hold a family together, a sense of community. Sure, the Puerto Ricans play their radios loud, they play dominoes in the street and they drink a lot of beer out of one-pound bags (at a party once, someone asked my friend Jose Torres to go out for “24 bags of beer”). But for me, that has made Brooklyn a more exciting, more lively place. You can measure a city by the life in its streets, and the Puerto Ricans have brought life with them: abundant, rowdy and baroque.

It is true that parts of Brownsville now look like Hamburg in 1945. Entire blocks have been abandoned to the rats and the wind. Old temples from the days when this was a Jewish area are now boarded up, or have given way to Baptist churches. The Gym at Georgia and Livonia, where Bummy Davis used to train while the Murder, Inc. goombahs looked on benevolently, is now gone; a big sign saying FORTUNOFF’S FOR MAH-JONGG SETS covers the windows, and you wonder how many people in the neighborhood play mah-jongg these days. (Milton Gross from the Post lived around that neighborhood, and I wonder if he was there that day 25 years ago when my father took me out to watch Davis with a bunch of other fight buffs in somebody’s old Packard.) Near P.S. 174, there is one of those Mondrianesque cityscapes—blue, yellow, pink squares that were once the walls of kitchens and bedrooms, where people loved each other, and quarreled late at night, and cried angrily at the meanness of poverty, and then moved on. You can still see an occasional Dairy Appetizing store out there, and Carlucci’s on the Brownsville end of Eastern Parkway is still one of the best Italian restaurants anywhere. But there remains this feeling of walking through purgatory. Street after street has been leveled. Only later do you discover that much of this demolition is part of a Model Cities plan, and that those streets will again be alive with children, and perhaps even trees. (But where are all the people now? Where on God’s poor earth did they go?) In Ocean Hill-Brownsville (the school district, not strictly the neighborhood) there is a revolution of sorts under way. It is led by people like Rhody McCoy, his governing board and the Rev. John Powis of Our Lady of Presentation R.C. Church. They are working at the hardest part of any revolution: the part that goes beyond posture and mere defiance to accomplishment. They understand what the Board of Education and various other bureaucracies staffed by suburbanites don’t understand: that the key is community. If they lose, Brooklyn loses, the city loses, we all lose.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard seems to be on its way back. A group called CLICK (Commerce, Labor, Industry Corporation of Kings)—started by people like Stanley Steingut, Brooklyn Borough President Abe Stark and Congressman Hugh Carey—has joined the City of New York (mainly the Economic Development Administration, with the help of another Brooklynite, Commerce Commissioner Ken Patton of Park Slope), to bring the Yard back to life. They hope eventually to provide between 30,000 and 40,000 jobs in the Yard by attracting civilian investment. They have signed a contract with Sea Train Inc., which will employ more than 3,000 workers in its first 18 months. The Yard, which covers 170 acres, already houses several small companies, such as the Rotodyne Manufacturing Company, which employs 130 workers building industrial ovens. The city is processing dozens of other applications. It might not come back to even the last payroll (1963: $201,000,000) for quite a while. But the beginning has been made. The governing factor in the city’s decisions to rent space is that the space must be used for jobs. They will not rent space for warehouses, and have already turned down one request from the Federal Bureau of Prisons, which wanted 12 acres for a jail.

Not far from the Yard, the Pratt Center for Community Improvement is drawing plans for the revitalization of the entire neighborhood near the Yard: Fort Greene, Williamsburg, Bedford-Stuyvesant. Among many other plans, they hope to set up a series of nurseries along major bus routes leading to the Yard, so that working mothers from Bed-Stuy will be able to drop off small children on their way to work and pick them up on the way home.

Out in Flatlands, a new Industrial Park is being built on 96 acres, to provide 7,000 jobs, and three plants are already under construction. The Brooklyn waterfront continues to outstrip the Manhattan waterfront in construction of new piers and rehabilitation of old ones. Two new department stores are planned for downtown Brooklyn, and the Brooklyn store of Abraham & Straus has now passed Bloomingdale’s in net sales. The Downtown Brooklyn Civic Center is now complete, and if the architecture rather resembles Abe Stark Stalinist in manner, it is at least new and it functions. Coney Island seems to me to be in decline, with the amusement area shrinking, old saloons like Scoville’s gone, the old bungalows on the side streets battered away, many proud houses gone seedy and squalid. But I’m told that last year Coney Island had its best year financially since 1947. The 12-acre site of Steeplechase Park will become a public park backing on the beach, and the aquarium is planning a 5,000-seat whale and dolphin area.

The Brooklyn Academy of Music has gone through a real rebirth in the past two years, something that startles old Brooklynites who thought of the Academy as a shambling pile located down the street from the Raymond Street Jail, and given over to travel lectures about the sex life of West Papuans. Today the Academy has become the dance center of the United States, possibly of the world. And it is avoiding the Lincoln Center aura of gilded society and class distinctions by giving special rates and tickets to poverty agencies, so that young people from all over the city can see modern dance, often for the first time. For those of us who used to go downtown to meet friends coming out of jail, to pick up girls at the dances at the Granada Hotel, or to box at the YMCA gym on Hanson Place, it all seems very strange; not many of us ever throught that the Academy would be thriving and the Raymond Street Jail would be closed.

There remain real problems in Brooklyn. There is still desperate poverty in the slums. Many urban renewal projects are still exercises in urban demolition. There are still too many decrepit, aging public schools, and the parochial school system remains a fragmenting anachronism. Eugene Gold, the Brooklyn District Attorney and one of the best of a new breed of elected officials in Brooklyn, told me that drugs and violence remain major problems. “I would say that drugs contribute in one way or another to about 50 to 70 per cent of the borough’s crime,” Gold said recently. “I don’t mean simply arrests for pushing or possessing drugs. I mean, in addition, drugs as the cause of other crimes: burglaries, stick-ups, muggings and the rest. We have a drug problem in every part of this city. When I go into Bedford-Stuyvesant to talk to people, as I do as often as I’m asked, they have one concern: how to stop crime. How to stop drugs. It’s a real problem.”

My own observation is that heroin seems to have declined. Most of the old junkies from my neighborhood are either dead or in prison, and the ones who remain are thought of as freaks. But marijuana is everywhere, and pills are easily available. Unfortunately, this is not just the problem of Brooklyn. The suburbs have the problem too. Last year, when I was spending some time in good old right-wing conservative Orange County in Southern California, drug arrests among young people had gone up almost 50 per cent in one year. There is no way to escape drugs by moving out. In California, they even arrested Jesse Unruh’s son on a pot charge.

It seems to me that despite the problems, Brooklyn has become the only sensible place to live in New York. Much has changed since I was a boy, but what the hell. If you consider jars of mixed peanut butter and jelly as the final sign of the decline of a great nation, people my age think the same thing about that modern abomination, the manufactured stickball bat. It is, after all, a terrible thing to deprive a kid of the chance to acquire lore, and the lore of the stickball bat is arcane and mysterious. Nevertheless, on the first day of spring this year, with a high bright sun moving over Prospect Park and a cool breeze blowing in from the harbor, I bought one of the abominations, and a fresh spaldeen, and talked some of the local hippies into playing a fast game. It was the first time I had played since moving away from Brooklyn, and in one small way I wanted to celebrate moving back.

We played in the old skating rink at Bartel Pritchard Square, and the young lean kids with the long hair simply could not hit the ball. They might have been playing cricket. But the first time up, I smacked one long and high, arcing over the trees, away over the head of the furthest outfielder. On the old court at 12th Street and Seventh Avenue, it would have been away over the avenue, at least three sewers, and probably more. Standing there watching the ball roll away in the distance, I realized again that despite all the drinking, sins, strange cities, remorse, betrayals, and small murders, there was still a part of me that had never left Brooklyn, that wanted desperately to stay, that was still 14 years old and playing stickball through long and random days and longing to be a Great Heart. I hoped that Carl Furillo, wherever he was, was shagging flies with an honored antique glove, and hearing the roars in his ears from the vanished bleachers.

The next time up, I grounded out, but it didn’t really matter.