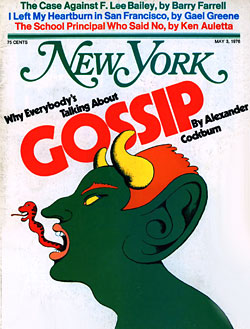

From the May 3, 1976 issue of New York Magazine.

“Never lose your sense of the superficial” was the peremptory advice once given his editors by Lord Northcliffe, the founder of modern popular journalism. They’ve been following his advice in England, more or less, ever since. In the United States, on the other hand, where journalists have a higher view of their calling, it looked for a while as though seriousness and deep purpose were carrying all before them: reporters discarded the brashness of The Front Page for the solemnity of All the President’s Men. But all is not lost. It’s become evident over the last few months that more and more members of the Fourth Estate are recollecting the essential meaning of their trade, which is to discover the inconsequential and get it into print.

The spirit of triviality lurking in the bosom of the average newspaper reader will never be quenched, and is indeed now blazing up more fiercely than ever before. For a decade the dark clouds of the Vietnam war, of Watergate, of the recession, seemed to obscure the landscape. Now, with a “recovery,” with the placid realities of structural unemployment and the prospect of a more or less steady run to the grave under either a Republican or a Democratic president, it is plain that what a large section of the literate citizenry is after is plenty of rousing chatter about other people. Gossip, in fact, has crawled out from under its stone and is now capering about in the full light of day.

There are, of course, problems with the word itself. In old thrillers the villain, advancing on the pinioned hero with whip and thumbscrew, used to say suavely, “Not torture, my friend. Shall we just call it … persuasion?” Something of the same coyness now seems to envelop the notion of gossip

Readers, hurrying home from the supermarket with copies of People, the National Enquirer, and the Star, tell you that they are just out for entertainment; reporters, bearing down on their victims, say they are after the facts; editors, with all due primness, tell you the public is now interested in personalities, and given half a chance will throw in a short lecture on the passing of the issue-oriented sixties. The truth of the matter is that they are all chasing after gossip, but like the old villain are too polite or are as yet unprepared to call the thing by its proper name.

“Gossip?” says Richard Stolley, managing editor of People. “We have expunged that word from our vocabulary. The term has held connotations of untruthfulness. If we’re asked to describe what we are doing we prefer to call it ‘personality journalism’ or ‘intimate reporting.’” That’s awfully nice for Stolley, perched atop a circulation for People which is now reaching 1.8 million. I hope he sleeps the better for having the notion of “personality journalism” tucked under his pillow. Readers, scurrying out to buy last week’s edition of his magazine, which has on its cover the words BARBRA STREISAND: FOR THE FIRST TIME, SHE TALKS ABOUT HER LOVER, HER POWER, HER FUTURE, presumably have a rather more zestful outlook on the situation.

Stolley is right, of course, in saying that the word “gossip” does have louche undertones. It is one stage nastier than “chatter,” one stage seedier than “investigation.” It’s poised between rumor and the real, between the stab in the back and the handshake, between tastelessness and the libel lawyer’s office. True gossip is only barely fit to print, is the rank underbelly of journalism. In the words of James Brady, vice-chairman of the Star, gossip is difficult if not impossible to confirm, but contains the elements of an accurate story. Gossip, in short, is nasty.

People magazine is right at the top of the ladder between decency and outrage. We find it near heaven along with the sedate chatter in the New York Times’s “Notes on People” section. A little below, we find “People” in the Washington Post “Style” section. Then down we go, past Suzy, Maxine Cheshire, Liz Smith, Herb Caen, Sid Skol-sky, Earl Wilson, WWD, Interview, “The Ear” in the Washington Post, Sally Quinn, Ben Bradlee’s memoirs, Rona Barrett, Cindy Adams, down, down into the caverns of the Star and the National Enquirer where spectral images of Jacqueline Onassis, Elizabeth Taylor, and Princess Margaret shriek for release from their eternal torment—a torment, incidentally, from which the entirely fictional French gossip sheet France Dimanche has just liberated Princess Margaret, since its headline recently announced LE SUICIDE DE LA PRINCESSE MARGARET.

In the pantheon of gossip it’s becoming clear that a certain shift in personnel is occurring. Jostling in among film stars, royalty, and international refuse of every description have come “media stars” and, increasingly, politicians. A certain widening of gossip’s focus is in fact taking place.

The most optimistic assessment of this new situation comes from a man who is in fact one of the true pioneers of a whole style of gossip—even though he resents the term. Lloyd Shearer started “Walter Scott’s Personality Parade” in Parade magazine in 1958. About 20 million copies of Parade are presently inserted into 111 newspapers across the country, giving “Walter Scott” a readership of around 50 million people. And each week, addressed to “Walter Scott,” come about 6,000 letters, mostly to get the facts straight about whatever piece of gossip happens to be on the writers’ minds: “Is it true that Henry Kissinger is a secret massage-parlor freak?” “Who is the French blonde whose name has been linked with Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands?” Each week “Walter Scott” gives them the facts.

The pleasure of his column, so far as I’m concerned, is that you can eat your cake (the gossipy question) and have it too (the factual answer). I asked Shearer if he detected a new trend.

“I don’t think gossip is on the increase at all,” he retorted. “We don’t traffic in gossip. Rumors and gossip originate somewhere else, and people write to us and ask if in fact something is true, and we spend a large amount of money and time checking it out among various sources. I think what has happened is that there has been a great growth of skepticism about people, which is understandable after the Kennedy; Johnson, and Nixon administrations. So there’s mounting interest in politicians.”

“… Gossip kept Watergate going and gossip seems to be seeing it into the grave: pain for Pat Nixon, pleasure for the people …”

Over the years, Shearer says, Parade has received fewer and fewer letters about film stars, once the staple of the column. “What has happened is that motion pictures are no longer the mass medium in America. Motion-picture stars were once the most colorful people in the world’. Now that television has surpassed and supplanted motion pictures as the prime medium throughout the world, the stars of television are very circumspect, because the people who sponsor them won’t put up with any nonsense. So you have in the mass-entertainment medium people who are not particularly colorful, not particularly maverick. I mean, what do you particularly want to know about Paul Newman? People know all about Barbra Streisand already, or they don’t care anymore. As a matter of fact there’s been a tremendous decline in the Walter Winchell type of gossip column. One of the reasons why the Los Angeles Times dropped Joyce Haber was there just wasn’t enough material. She had to use names that were fairly esoteric in Peoria, Illinois. So, as you get a more educated electorate and because of circumstances, the readers are more interested in politicians and publishers. People are not so much interested in gossip as they are in truth.”

This, you might say, is the up-side view of the whole gossip phenomenon. And, as if in testimony to such uplifting sentiments, the Sunday before last the cover of Parade presented Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein to its 50 million readers. Now Woodward and Bernstein—particularly in their recent investigative activities as displayed in The Final Days—have cast the whole matter of gossip in a particularly interesting light. Stimulated by Watergate, young people have been filling the nation’s journalism schools, eager to learn the tricks of investigation and then hurry on out to expose evil men and possibly also to save the Constitution. Ecstatic with high purpose, they doubtless avoid undue consideration of the thought that Watergate, if it started with the Dahlberg check, seems to be ending with the news that Richard and Pat Nixon did not sleep together for twelve years.

Woodward and Bernstein have naturally defended all the allegations in their recent book on the grounds (a) that they are true and (b) that disclosure of these truthful allegations is essential to the understanding of the political personality of Richard Nixon. Maybe so, but the fallout is pure gossip—as is plainly revealed by the cover on the Star last week, which bears the headline PAT NIXON DRINK AND SEX CHARGES: FRIENDS TELL INSIDE STORY. The Star, at least, knows where the game is at. So indeed, in a more tasteful way, did Newsweek when it first presented excerpts from The Final Days. Gossip kept Watergate going and gossip seems to be seeing it into the grave: pain for Pat Nixon, pleasure for the people.

Some of the more seasoned practitioners, well aware that gossip can cause pain, emphasize that they try to keep clear of inflicting such damage. Suzy (Aileen Mehle), for example, now appears in 89 newspapers going out to between 15 million and 20 million readers. Right at the start of her career she decided that the one thing she did not wish to confront for the rest of her working life was a roomful of people recoiling from her as at the sight of a viper. She also wished to keep her sources. “I knew about Princess Margaret and Roddy Llewellyn right from the start. Was I going to print it? No way!” So the nearest she’ll get to conceding any aggressive edge to her project—which she defines as “sending it all up”—is to say that “I give them the needle, but in a way that they don’t feel till three days later.” Nor does she particularly feel that anything much new in the way of gossip is happening. “Gossip is the juice of life, but we’ve always had it.” And, in a spirit of peace, off she plunges to her parties and her people.

Herb Caen similarly thinks that nothing new is going on. Caen, for those who have not sampled the unique pleasures of his column in the San Francisco Chronicle, is one of the best as well as longest-practicing gossips in the United States. “Gossip has never gone out. It’s another media hype. I started writing gossip in high school in 1930 and it hasn’t changed since then. That was 45 years ago. I told who was holding hands with whom in the parking lot and everyone wanted to read it. It’s still the same business. I don’t see any change. I think there were better gossips in the old days than there are now. The Los Angeles Times is trying to get by without Joyce Haber, but people are screaming bloody murder. Even though she was one of the worst, and very heavy-handed, people still wanted to read it. People look for something light. They don’t want to read the Time essay, they want to know what Princess Margaret was saying to Nureyev, which is why People was started.”

But at least Caen is prepared to accept the nastier side of gossip. “There’s gossip and chitchat. Chitchat is lighter in vein. Gossip should have some scandal to it. It’s got to be a little nasty. A little bit of going for the jugular. Otherwise, what the hell’s the point of it? I try to make it as nasty as possible, within the realms of good taste and the libel laws. There’s a little bit of the cobra in all of us. People is just a bore, no knife edge to it at all.”

And then Caen started talking about the British gossip columns. “They’re marvelous,” he shouted enthusiastically. “They’re tougher … my idea of what a gossip column should be.”

“Knife edge …” I wonder if people now gossiping about gossip, peering at Truman Capote fingering his stiletto on the cover of this month’s Esquire, really know what might be in store for them. They could, of course, recall the manipulative savagery of Walter Winchell—blackmailing his subjects and touting stocks. But they might also peruse some of the British newspapers today, or—to be really thorough about the job—go back through the newspaper archives to the late 1950s when the art of the British gossip column was at its height.

In 1961 Penelope Gilliatt—the novelist, screenwriter, and New Yorker film critic—concluding a drive from London to Sussex in the company of the playwright John Osborne, climbed from the car to view their secret trysting place in the quiet village of Hellingly. Her pleasure was marred by the sight of a Fleet Street gossip columnist climbing out of the trunk of the same car, where he had—at great personal danger—secreted himself during the drive from London. The columnist forthwith proceeded to take photographs. From the hedgerows sprang other columnists also in pursuit of evidence of the Gilliatt/Osborne liaison. Osborne was married; so was Gilliatt, to Tony Armstrong-Jones’s best man. The couple retired—for the duration of their stay—to the sanctuary of the cottage, later to be informed by the neighbors that these same neighbors had been offered large sums for news of “quarrels” and other domestic commotion.

Gilliatt had made the mistake of writing a fierce expose of gossip columnists in Queen magazine in 1960. This was around the time that three journalists from the William Hickey column in the Daily Express had striven, in a couple of cunning ways, to enter a private party thrown by J. Paul Getty. One had disguised himself as a member of the band; the other two had hidden in the shrubbery and at an appropriate moment had emerged in full evening dress, clutching champagne glasses filled from a quarter-bottle brought along for the purpose.

It was also around the time—as related by Gilliatt—that the gossip writers had become angered by the refusal of the wife of one cabinet minister to reveal her private country address. A reporter telephoned her townhouse, pretending to be her child’s godfather, told the housekeeper that he had a present that he wanted to get to the child, and on hearing that the nurse was going down to the country the next day and would take it, waited outside the house and followed her to earth.

Gilliatt discussed such practices; the elaborate stringer and payoff system maintained by the columnists; their innumerable cruelties, inaccuracies, and snobberies; above all, their insane hypocrisy as they detailed the socio-sexual activities of the upper classes. Her article provoked bellows of remorse and surprise from press lords such as Beaverbrook and Rothermere. Some of the columnists were sacked, others directed to mend their ways.

Shortly thereafter, amid the final spasm of the Profumo scandal, the art of British gossip-writing fell into a long decline. In its place came the jocular muckraking of Private Eye, the biweekly satirico-investigative sheet. Rather along the lines of Lloyd Shearer’s present emphasis on people’s lust for the truth as opposed to mere gossip, Private Eye detailed the activities of politicians, newspaper people, publishers, and the like. The order of the day was investigative journalism, or at least satirically investigative snippets.

At the start of the 1970s it became clear that the most readable stuff in Private Eye was, as signed by “Grovel,” nothing other than our old friend Gossip in a fresh and somewhat tougher guise. “Grovel” was and is the work of Nigel Dempster, the man singlehandedly responsible for resurrecting British gossip-writing. At the age of 34 Dempster—who also writes a column in the Daily Mail—is flushed with triumph. He was, as he hastened to inform me the other day, the first person to reveal the full details of Princess Margaret’s affair with Roddy Llewellyn. He gained much notoriety at the time Lady Antonia Fraser joined forces with Harold Pinter, by listing her alleged previous lovers. On December 15, 1975, he predicted to the day the moment when Harold Wilson would resign. Unscrupulous, devoid you might say of all decency, he best expresses what gossip-writing is all about.

“I think American gossip is tedious in the extreme. It’s bad, it’s boring, and it’s about boring people. It’s not revelatory. It’s in no way intrusive. There’s nothing there that causes any distress, that causes any harm and dissension—which is what we should be all about. We are here to write about things that are not welcomed by the subject of our inquiries. American columns are nothing but puff P.R. jobs.”

“… Do people now gossiping about gossip, peering at Capote fingering his stiletto, really know what may be in store for them? …”

Dempster, announcing that he had just been soundly thrashed by a member of the British equestrian team resentful of his activities, warmed to his theme. “Gossip must be nasty, because it is per se what you would not wish to be heard and spread abroad about your good self. The targets are surely those people who sell themselves to the public, those people who wish to parlay and trade with the public. I feel that the public has a right to find out any aspect whatsoever of these people’s private lives. I go after privilege and I define privilege as existing for anyone with safeguards against the awful humdrum existence we are forced to lead, anyone who is elected to office, anyone who is in receipt of a title and uses it, anyone who uses the media to further his own ends, anyone who puts himself in the public eye for gain.

“My living doesn’t depend on anyone I write about. I made a conscious decision many years ago that I didn’t like a certain section of society, and as far as I’m concerned I’ve never had their society, their friendship, or their approbation and I’ve never sought it. That’s why I can write about whom I want. This way you don’t get those rather pathetic pleas to one’s better self, to one’s better nature—which I do not have.

“The one thing you’ve got to have in the gossip business is a target. In America there seems to be no taste, no instinct, no smell for it. There’s no inquisitiveness there. Watergate got out through people gossiping. Gossip is the color of life, the fine, bold strokes. By which I mean that you and I—the purchasers of gossip—find out what color socks Nixon wears or whether he sleeps with his wife.

“Our sort of journalism is grudge journalism. You only get tip-offs from someone who has a grievance of some sort. It’s all swordsmanship, in my view. I regularly get beaten up and things thrown at me. Two nights ago Harvey Smith [the horseman] hammered me into the ground. Last year I put myself up in a charity dance in front of all those idiots and they were able to throw pies at me. Ten pies at $50 each, and a dozen eggs at $20 each. I was in terrible shape for a while, but if you can’t take it, then don’t give it.”

Dempster, reaching his finale, delivered what was to my mind a fairly accurate version of what a lot of journalism and all true gossip is about. “I think human beings are unpleasant and they should be shown as such. In my view we live in a banana-peel society, where people who are having a rotten, miserable life—as 99.9 percent of the world is—can only gain enjoyment by seeing the decline and fall of others. They only enjoy people’s sordidness, their divorces, whether their wives have relieved them of $5 million, how their children turned round and beat the crap out of them. Then they suddenly realize that everything is well in the state of Denmark, that everyone else is leading a miserable, filthy life which—but for me and other journalists around—they would not know about. They see that those who obtain riches or fame or high position are no happier than they are. It helps them get along, and frankly that is what I give them.”

This sort of talk is, needless to say, a far cry from the encouraging noises made by purveyors of “personality journalism” such as Stolley. But Dempster—whose most recent coup has been to expose a Labor member of Parliament as a lesbian—talks of coming to the United States to run a syndicated gossip column. Perhaps he senses—as Truman Capote has sensed also—that the time is ripe here for true gossip. Dempster, a public-school boy in the twilight of Great Britain, is franker than many of his American counterparts about the realities of the trade: that almost all journalism in the end is gossip, and that the handmaidens of gossip are treachery, envy, and spite; that while many journalists may prattle on about the public’s right to know, they are in their bones talking about their own need to tell.

Maybe it is premature to set such a parallel between the terminal spasms of the British way of life and actual and impending ailments on this side of the Atlantic. The British, after all, have long had an obsession with the realities and intricacies of class and with the presumed drama inherent in the sex lives of public figures. “Intimate reporting,” as Richard Stolley termed it, need mean little more than a democratization of polite chatter, spreading out from Hollywood to encompass every profession in the country. As Stolley put it, “so-called superstars are now being produced in practically every field.” This means in the end, I suppose, that the respectable reporters and researchers of People—constrained by large advertisers, good taste, self-esteem, and the libel lawyers—will ultimately be able to write “personality profiles” about everyone in the U.S.

It depends how far along the road we go. Yesterday’s idols become today’s chopping blocks. President Kennedy’s sex life gets laid out in Time magazine. Joan Kennedy goes to a sanitorium for a cure for alcoholism and a couple of fellow patients sell the story to the National Enquirer. In a spirit of tranquil expectation the readers wait for more, read—maybe with outrage—but still read.

Perhaps, in answer to such expectation, American newspapers will rediscover the gross popular tradition lost to radio and now largely kept alive by British and Australian journalists on the Enquirer and the Star. Perhaps American journalists will slowly descend again into the mire from the pinnacles of high-minded respectability, of status-sodden intimacy with the likes of Henry Kissinger. Perhaps publishers, sensible of the importance of newsstand and supermarket sales, will push them in that direction anyway.

“Gossip?” said Gore Vidal. “Gossip is conversation about people. In the United States there has never been actual discussion of issues whenever a personality could take its place. We do that because we can never examine the sort of society we live in. Therefore candidates are rated according to their weight, color of eyes, sexual proclivities, and so forth. It avoids having to face, let us say, unemployment—which is a very embarrassing thing to have to talk about. Anything substantive is out. Otherwise somebody might say this is a very bad society and ought to be changed.”

Defenders of gossip will doubtless controvert Vidal’s gloomy assessment, point to crusading gossips in the tradition of Drew Pearson—who fulfilled the gossip’s first function of simply daring to print the previously unprintable. The example of Pearson, the reporter-gossip, is a noble one and the sort of thing Lloyd Shearer evidently had in mind when he talked about people’s desire for truth. But I’m not so sure it has much to do with the general trend of gossip, which has something to do with simple curiosity, much to do with snobbery, envy, cruelty, the fostering of antagonism, knowingness rather than knowledge, the creation of coteries and a perversely heightened sense of the trivial.

Who knows, though? Maybe People magazine will successfully domesticate gossip in the way that the American mass media have domesticated so much else, and the readers in search of thrills will come upon only sanitized fun, mere pap to trundle home from the supermarket.