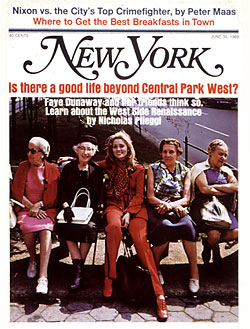

From the June 30, 1969 issue of New York Magazine.

Five years ago the West Side of Manhattan was considered such a dangerously blighted area that invitations to parties on Riverside Drive were often rejected, large rent-controlled apartments were voluntarily given up and even Chicken Delight wouldn’t deliver. Today, while many of the area’s most critical problems remain, an unmistakable mood of confidence has replaced earlier premonitions of doom. Merchants, real-estate men, bankers, theatre owners, city planners, restaurateurs, newsdealers and the trustees of private schools all agree with what Mayor John V. Lindsay admits privately: “The Upper West Side is probably enjoying more of a renaissance today than any other single neighborhood of our city.”

In the 64-block-long area west of Central Park between Columbus Circle to the south and Columbia University to the north, the evidence is visible. Not only are there new low-and middle-income housing developments now where the rubble of abandoned buildings and slums stood just five years ago, but hundreds of the area’s crumbling rooming houses have been renovated to accommodate increasing numbers of middle-class tenants, and even a few of the neighborhood’s middle-European rococo hotels have been steam-cleaned. The same kind of young, successful and relatively affluent middle-class families that moved to the suburbs 20 years ago and to the East Side 10 years ago are moving to the West Side today, and while the neighborhood still has an ample supply of teenage muggers, parading homosexuals and old men who wear overcoats in July, the over-all mood of the area seems to have changed.

More baby carriages are in evidence; young, long-haired lovers are sharing park benches with elderly socialists; hiphuggered mothers are getting fewer dirty looks from resident matriarchs; tall blonde girls in pantsuits are suddenly bouncing down Columbus Avenue; there are see-through blouses in the windows of stores that used to display black crepe dresses and pillbox hats, while borzois, miniature poodles and Basenjis are beginning to outnumber the mongrels. Some of the new West Siders have moved back to the city from the suburbs, others have moved to escape the high rents of the East Side or the small apartments of Greenwich Village, Chelsea and even Brooklyn Heights. Many insist the area offers better housing values, transportation (70 per cent of all Manhattan public transit is on the West Side) and park space (twice as much as the East Side). The West Side is flanked by Central Park on its east-and the 266-acre Riverside Park on its west. Having the two parks within four crosstown blocks of each other (nine blocks separate Central Park from the largely commercial riverfront on the East Side) has encouraged movement through the area, despite the fact that stories of muggings and burglaries cast a paranoiac pall over much of the community.

“I was ready for war,” one recent brownstone buyer said. “You know, German shepherd, barbed wire, burglar alarms, punji sticks, the works. But we were delighted to find that with a little caution it could be a relaxed place to live.”

Statistically the West Side’s 1968 crime figures place the area in the unenviable top third of the city’s 76 precinct-house totals. The 20th Precinct on West 68th Street and the 24th on West 100th encompass most of the Upper West Side, and their combined records show 36 homicides, 86 forced rapes, 8,478 burglaries, 1,097 felonious assaults, 3,233 robberies (muggings and stickups) and 6,762 larcenies (mostly pocketbook snatches) last year. The bulk of the West Side’s street crime today is the work of roving bands of 14-to-20-year-olds who mug, jostle and threaten their victims around or near the neighborhood parks during the evening and early morning hours. The effect of these crimes, committed, it sometimes seems, on everyone, or at least a friend or relative of everyone on the West Side, has been to create an atmosphere in which sudden noises produce quick frightened looks.

The Upper West Side is awake. A few years ago even flowers didn’t want to grow there,but today a $700 million building boom has (almost) everything coming up roses.

Business, of course, has joined and helped to stimulate the movement to the West Side. Flower vendors who set up their cardboard cartons at the top of the neighborhood’s subway stairs claim business is booming.

“Only a year ago,” Monroe, a West 86th Street vendor, said between sales, “flowers couldn’t live on the West Side.”

Many of the new storekeepers who have moved into shops along Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues say that just a year ago they could not have survived. Jane Wilson, who in February opened a relatively expensive quality catering business called The Party Box on Columbus Avenue at 86th Street, admits that much of her business comes from the brownstone and luxury-apartment families who are as new to the neighborhood as she is. The bedpan, truss and traction medical supply stores that used to blanket the West Side have been replaced by youthful boutiques (Charivari, Free Expression, ICC Sound Union, Creations ‘n Things, The Looking Glass), bookstores, theatres, antique shops, and a proliferation of moderately priced Cuban, Japanese, Thai, Italian, French, Indian, Egyptian and Israeli restaurants. New stores, like a dazzling unisex boutique, have even opened in what was once a commercial no-man’s-land on Broadway between 105th Street and Columbia University.

Michael O’Neal, the owner of The Ginger Man near Lincoln Center, claims his restaurant and bar business has quadrupled in the last few years, and he does not attribute the entire increase to his white marble neighbor. “Lincoln Center used to be all there was on the West Side, but now the whole area has come to life. We plan to open a new place at Columbus Avenue and West 73rd Street this fall.”

Business on the West Side is increasing at such a rate that Stanley Zabar, of Zabar’s Gourmet Foods, long a West Side landmark at Broadway and 80th Street, plans to triple his store’s size in September when he moves the entire operation to new quarters two blocks north. “Just five years ago it was considered an adventure, a trek, even dangerous, to come to the West Side and shop in our store,” he recalled. “Shopping guides, newspaper stories and magazine articles were always knocking the neighborhood when they wrote about the store. That doesn’t happen anymore.” Theatrical producers Joseph Beruh and Edgar Lansbury felt so confident about the area that last month they opened the Promenade Theatre, an off-Broadway theatre, on Broadway at 76th Street. Their first production, Promenade, a musical by A1 Carmines and Maria Irene Fornés, was admired by New York Times critic Clive Barnes, who strolled over from his own West 72nd Street apartment to review it.

Perhaps the most significant announcement concerning business on the West Side came on March 18, when Alexander’s Inc., one of the city’s largest retail chains, revealed plans to build a $10-million, six-level, 230,000-square-foot department store and a 1,000-seat movie theatre at the corner of Broadway and 96th Street. A two-year study of the area, commissioned by Alexander’s, substantiated in statistics what many of the area’s merchants had begun to suspect. The West Side, the study pointed out, was in a state of transition in which more and more high-income people were moving into the neighborhood all the time, reversing the trend of the ‘50s, when the same kind of people were being drawn out of the center city. The survey also showed that Alexander’s would have access to a total West Side population of 800,000, including 360,000 Upper West Side residents, with a surprisingly high average disposable income of $3,970 when compared to the East Side average of $4,410.

Jason R. Nathan, the city’s Housing and Development Administrator, who recently led some municipal bond investors through the West Side renewal area, said even they were amazed.

“These men are really very important, very conservative cats,” Nathan said, seated in his office facing a Mobil Corporation street map of New York City taped to the wall.

“The truss and traction stores have been replaced by boutiques, theatres, antique shops and a proliferation of restaurants.”

“They were stunned by what’s happening on the West Side. They felt it was the most striking piece of city revival they had seen. I can tell you they were impressed.

“The success of the West Side’s renewal was always in question until about a year ago. In concept the area has a fantastic economic mix, ethnic mix, architectural mix. It has mass and scale. It was always worth preserving. There was simply too much there worth saving to subject the whole of it to the bulldozer approach.”

Businessmen and apartment-starved New Yorkers were not the only people showing confidence in the West Side boom, however. The board of trustees of the Calhoun School, a private elementary and preparatory institution founded in 1896, announced they were rejecting, after two years of consideration, a proposal to leave the West Side and merge with a private school in Riverdale. Irving Stimmler, a school trustee, said on May 18 when the announcement was made, “We believe in the West Side. We feel that once more this is the coming place. This is where the future is.

“It would have been so easy to move to the suburbs, a marriage of convenience with instant expansion. But the question really was, ‘Do we want to give up the ghost and become just another exclusive school catering to the upper classes?’ Most of our students are going to end up in the city, and how are they going to cope if they’ve been educated in the suburbs? We’re a city school. A West Side school. We decided to stay and fight it out here.”

The residents of Manhattan’s Upper West Side make a yeasty polyglot society that is as ethnically diverse and economically varied as any area in the United States, with the possible exception of Honolulu. It is a neighborhood, or series of neighborhoods, where certain recently renovated brownstone blocks have already taken on the hushed tone of affluence, while around the corner young Puerto Rican men, wearing sleeveless underwear and religious medals, spend most of their Saturdays rubbing Simoniz wax into six-year-old automobiles. It is an area in which Mrs. Jacqueline Onassis sends her son to a school that is within a block and a half of a Japanese supermarket, an Israeli coffee house with a floor show, a gypsy palmist, a hardware store specializing in “Bueno Bargains,” an excellent Jewish delicatessen (Gitlitz), a pizzeria, a Lebanese restaurant (Uncle Tonoose) and a religious-articles store that sells evil-eye repellents, love potions and numerology books. (The window of the tiny shop holds a life-size statue of a saint, some votive candles and a Mastercharge credit plan decal.) It is an area that houses, besides many Russian, German, Polish, black and Puerto Rican residents, substantial numbers of Japanese, Chinese, Mexicans, Haitians, Irish, English, Dominicans, Norwegians, Swedes, Czechoslovaks, Austrians, Italians, Canadians and Midwestern Americans.

The West Side is an area of such variety that it appears as though some percentage of just about every ethnic, religious, economic and social group that ever lived there has stubbornly insisted upon remaining. In fact, in 1907 a charitable foundation built a 350-apartment tenement on West 64th Street for West Indian domestics, and today there are still 650 people living in those apartments, most of them descendants of the original tenants. The Upper West Side was first populated in the 1830s by wealthy New York Protestants who maintained bucolic summer residences near what is now Broadway and West 93rd Street. The area remained a predominantly WASP community (there are still seven Episcopal churches and a cathedral) through the Civil War and into the 1890s, when large numbers of Irish immigrants moved into the area to help build the Amsterdam Avenue steam elevated as well as the tenements along Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues. By 1910 the Irish were predominant, and Tammany politics and the dark mahogany bars of Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues (many are still there) ruled the West Side. The first Russian, Polish and German Jewish families began moving into the area about that time. To these people, most of them having moved from the crowded tenements of the Lower East Side, Chelsea and parts of Harlem, the West Side was the suburbia of the day. In the late ‘20s and early ‘30s the construction of the IND subway line created a tremendous building boom, despite the Depression, and it was during this period that many of the massive stone and brick apartment houses that line Central Park West, West End Avenue, Broadway and Riverside Drive were built. At approximately the same time in Germany the rise of Hitler and Nazi anti-Semitism forced many prominent and well-established German Jews to leave their native cities and flee to other parts of the world. Many who had relatives or friends in the United States moved to the West Side. By 1938 they outnumbered the West Side’s Irish population.

The West Side was the reception center for a forced emigration of professionals, the wealthy and the educated, and it gave the area a decidedly intellectual, middle-European flavor. The West Side never lost that quality, and there were always bookshops in the area, newspaper stands with foreign journals and magazine stalls crammed with little intellectual publications. As a result of this continued intellectual climate the area has always attracted writers, editors, playwrights and critics. Three months ago Lewis Nichols of the New York Times wrote: “An excellent case may be made out that the West Side of Manhattan, lying between Central Park and the Hudson, now has taken over from the Village.” Nichols attributes economics, the area’s large, well-constructed if somewhat faded buildings, its informal “sweater and chino” style, its spectacular Hudson River views, and Riverside Park as the main reasons for Isaac Bashevis Singer, Thedore Reik, Pauline Kael, Judith Crist, Clive Barnes, Roger Butterfield, Alfred Kazin, Frederick Morton, Joseph Heller, Eliot Asinof, Jack Gelber, Robert Lowell, James T. Farrell, Gerold Frank, Murray Kempton, Murray Shisgal and Jules Feiffer’s living there.

The visible blight of the West Side could first be seen shortly after World War II. The citywide housing shortage that followed the war caused over-crowding, and the large apartments and residence hotels of the West Side were quickly partitioned into small apartments and furnished rooms to take advantage of the situation. The deterioration of the West Side actually began in 1939, during the World’s Fair, when the city attempted to alleviate a drastic housing shortage by passing a law that made it profitable to break up large apartments and reclassify one- and two-family brownstones into rooming houses. During the war the shortage worsened. Blocks that once held several hundred tenants now were jammed with thousands, and most of them were transients, troubled and lonely. The area’s traditional “mama and papa” landlords moved out. Speculators moved in. By the early ‘50s housing on the West Side had deteriorated to such an extent that Mayor Robert F. Wagner appointed the Mayor’s Slum Clearance Committee under Robert Moses to rebuild the area. This agency compounded the chaos of the West Side by turning over to unscrupulous housing “redevelopers” huge sections of the area for demolition while thousands of families still lived in the buildings. Little or no attempt was made to relocate the area’s predominantly low-income families when their homes were torn down, and many were forced to move in with relatives and friends nearby. Once demolished, the old tenements were often replaced by parking lots or luxury housing, but the most common practice among the “redevelopers” was to allow the condemned buildings they had appropriated to remain standing. From these constantly deteriorating buildings developers exacted exorbitant rents from desperate tenants while supplying no services, heat or maintenance. The Welfare Department began filling the furnished rooms and crumbling hotels of the West Side with the city’s most socially dependent and antisocial citizens. Soon junkies, prostitutes, the retarded, petty criminals, dischargees from state mental hospitals, young mothers with dependent children, the enfeebled, the blind and the destitute were all jammed into the squalor of a decaying neighborhood. As a result of that policy there are still 24,500 of the city’s 32,000 single-room occupants living on the West Side, and it was not until two years ago that the ‘first serious efforts were made to give these residents the kind of heavy-duty, concentrated assistance that they require.

Only the hardiest of city dwellers remained on the West Side during its period of blight—they, and their impoverished neighbors who had no choice. High crime rates, poor schools, indifferent bureaucrats, corruption and graft—all of the classic characteristics of urban disaster—were visiting the Upper West Side in the ‘50s. The result, however, was surprising. It created the most skeptical, municipally wise, politically organized, reform-conscious community in the city. West Siders became the nightmare of city bureaucrats. Citizen groups were formed, and soon there was very little about building codes, city officials, law enforcement, health regulations, education, welfare, relocation, the legislature, youth activities, real-estate assessments, political patronage, corruption and judgeships that they did not know. It was this community movement that became the basis of the Reform Democratic clubs of the West Side, which eventually replaced the Regular Democratic clubs. In Joseph Lyford’s Airtight Cage, an excellent book about the West Side during this period, he writes of these volunteer groups: “They were considered ‘bad news’ by many of the city’s bureaucrats and [were] incomprehensible to strangers. West Side activists talk of ‘skewed rentals,’ ‘title vesting dates’ and ‘inspectional coordination.’

“… Its decidely intellectual middle-European flavor has always attracted writers, editors, playwrights and critics …”

“They were sometimes so terrifying to bureaucrats that once a group called about the need for fixing some bathroom plumbing and the next day the city sent down 20 toilet seats.”

Lyford described the city’s “vast, informal machinery” at that time and the practice of funneling society’s disciplinary and health problems into the West Side. Just about every sector of the Establishment, he wrote, participated in running the machinery of urban decay or lubricating it: slumlords would rent to the dead as well as the living provided they got a good price. They received immunity from fire inspections, building codes, health regulations and rent control. City employees who collaborated in the arrangement got “gratuities.” The Welfare and Health Departments went along because they simply had no alternative. Judges slapped the slumlords on the wrist on those rare occasions when they were brought to court (in 1964 the average fine levied against a convicted slumlord was slightly over $18). “Approval of the system,” Lyford continues, “is given by business leaders who lead the fight against adequate welfare and housing; prosperous financial institutions that refuse to lend money for private investment in slum rehabilitation; foundations that avoid any significant commitment to abolition of the slum; labor unions that have abandoned the low-paid worker and practiced racial discrimination; and white and black political organizations that have a vested interest in segregation and race politics.”

In the face of such adversity the residents of the Upper West Side acquired a dynamic hardiness and a competitive spirit that is still very much in evidence. New residents soon learn to tolerate, if not join, their veteran West Side neighbors who blithely walk to the head of supermarket checkout lines, double-park their cars, ride bicycles on sidewalks, unleash their defecating dogs and beep their horns at traffic lights. It is a community of street participants. Curbside card tables line Broadway from West 72nd Street to Columbia University and dedicated petitioners snare, argue and shout with passersby about letting Biafra live, dumping the ABM and buying “scab” grapes. Assemblyman Albert H. Blumenthal, whose district takes in a 100-square-block area from about West 80th Street to West 100th, has 210 extremely active community organizations on his current legislative mailing list. “It is the most politically sophisticated district in the city,” Blumenthal smiled wanly. “During campaigns, or on the street, people come up to you and they know what you’re doing, what other legislators are doing and all of the subtleties of political life. For example, John Lindsay and I both won this district by the same percentage of votes, which means voters voted for him at the top of the line and then came down the machine and jumped over to me. The district’s voting patterns show tremendous discernment. It was the only white district in the city that voted by a large percentage for the Civilian Review Board.”

The West Side is a community in which aloofness is considered a sign of weakness. Busybodies abound. A gift horse on the West Side is considered Trojan until proved otherwise, and the announcement that Alexander’s planned to wheel in a department store was taken by many individuals and neighborhood groups as a declaration of war. In fact, on the night of a public hearing to consider zoning changes necessary before the new Alexander’s could be built, various West Side warrior groups were in the auditorium an hour early. About 120 local men and women listened quietly as a member of the Community Planning Board recapitulated what most of them already knew and then heard the department store’s lawyer tell them that Alexander’s needed the variance before they could build the store, that Alexander’s planned to employ between 750 and 1,000 people from the surrounding area, that the store would be built by fully-integrated union crews and that no residential tenants live on the proposed site.

“Anyone wanting to say anything, jot down your name,” Robert Schur of the Planning Board said after the store’s attorney spoke, and about one third of the audience rose and signed in.

A demure, round-faced black woman was the first speaker. She wore a blue pantsuit with gold buttons and a tan sweater.

“I think the promise of jobs is just an allurement,” she began, looking directly at the front row in which the store’s representatives were seated.

“Grave consequences will come to the neighborhood with the incursion of one large department store. Others will follow. Broadway and 96th Street could be as distressing a place to live as East 59th Street and Lexington Avenue with all that traffic and trucking that goes along with lots of department stores.”

She was cheered.

A young bearded man rose and said that both the Riverside and the Riviera movie theatres were being destroyed by the new store, even though Alexander’s planned to build a new theatre.

A representative of the West Side Hotel Association said Alexander’s would be a great asset to the neighborhood and would “attract desirable stores.” When he emphasized “desirable,” some of the younger people in the audience laughed and snickered.

A Puerto Rican man next addressed the crowd and said, “The Puerto Rican community has already had a meeting and we are opposed to Alexander’s move to 96th Street, and the reason was that this community needs more housing and schools. If they want to improve the neighborhood, why don’t they put up a school and call it Alexander’s the Great?”

A representative of the West Side Merchants’ Association rose and supported Alexander’s.

Another man, a local jeweler, followed and said, “In 30 years I’ve never heard of the West Side Merchants’ Association,” and then sat down.

Julia McCarthy, an attractive young woman with the Citywide Housing Coalition Committee, pointed out that the real danger with Alexander’s was not the traffic it would bring to the area, but the real-estate speculators. Most of the large, low-profit, rent-controlled apartment buildings around the site would increase in value, and it would not be long before lobbying speculators would gobble them up for commercial developments, thus evicting the middle-class and low-income families who live in them. She suggested that if the store’s zoning variance is to be given, a proviso that they build 200 public housing units above the store should be attached. She was loudly cheered by most of the audience.

The owner of an all-night Ping-Pong parlor on the proposed site explained that the new store would deprive neighborhood people of a recreational oasis. John Fiore, of the onsite EAT SHOP, said, “The stores they’re eliminating are the better stores. The best street is being demolished.” A young man explained that an ecology exists in cities and that to dump a huge department store in the middle of a block could throw the area off balance just as surely as putting polar bears in beaver ponds. The meeting ended, as do most community participation meetings, with no concrete accomplishments to look back upon.

“Alexander’s plan to wheel in a department store was taken by many residents as a Trojan horse … a declaration of war.”

Henry Marquit, chairman of the West Side Planning Board No. 7, which takes in most of the area, was pleased with the West Siders’ enthusiastic participation.

“We are having a renaissance up here, that’s true,” Marquit said, “but it is important to realize that this neighborhood is built upon a traditional base. This area has the best population mix in the city. An attempt has to be made to protect this balance, and the primary concern is housing.”

According to population projections of the Upper West Side based on 1960 census figures (72 per cent Caucasian, 15 per cent black and 13 per cent Puerto Rican), the area’s white population is expected to increase to 82 per cent by 1970. Keeping Manhattan from becoming a polarized borough of either rags or riches is something that many planners feel cannot be left to chance. Already, they point out, many of the Upper West Side’s residents are earning more than $15,000 a year, while the area still has an over-all unemployment rate higher than the rest of the city.

“People feel threatened,” Marquit continued. “The area could very easily become upper middle class like much of the East Side. Rent-controlled apartments are slowly slipping away. Well-maintained tenements with reasonable rents are becoming too valuable to remain as such. In addition, there is more to this ‘upper income’ business than most people care to admit. When it takes two paychecks to pay the rent, that’s not affluence. Many of us are convinced that the only way to maintain the area’s unique ethnic and economic mix is to get a master plan for the West Side to help shape its growth.”

Many West Siders agree with Mr. Marquit’s appraisal. City Councilman Theodore S. Weiss said that while he was delighted by some of the area’s development, he saw no guarantee that the renaissance wouldn’t continue until low-and moderate-income families could no longer afford to live there.

“In my building,” Weiss began, “which is uncontrolled, lease renewals have gone up 40 to 80 per cent. We lost six young families in six months. They could not afford to stay. On top of that is a very, very serious public safety problem. Schools present terrible problems to kids and they’re substantially worse in low-income areas where the system throws some of the most problem-ridden together. This renaissance can be misleading. It can be a rich man’s renaissance. A lot of East Siders have been caught in the housing squeeze themselves and the large cooperatives and brownstones and four-and five-bedroom apartments over here are becoming more and more tempting to them. The West Side is on the razor’s edge. It runs the terrible risk of becoming the East Side.”

The possibility that the West Side’s development may be running wild has not gone unnoticed by either Donald H. Elliott, the city’s planning commissioner; Jason R. Nathan, who heads the Housing and Development Administration, or any of the extremely active and knowledgeable local groups like the Lincoln Square Community Council. In the Lincoln Square area alone (Columbus Circle north to West 72nd Street and from Central Park to the River) over $358 million has been spent in commercial buildings and $321 million in luxury housing since the blossoming of Lincoln Center. (Land values in the area rose until today property in the Columbus Circle-Central Park West area costs $200 per square foot; Broadway between 61st and 69th Streets, $100 per square foot; 64th to 69th Streets between Central Park West and Broadway, $60 per square foot, and the Amsterdam and West End Avenue area from 59th Street to 65th Street is $35 per square foot. The increase has lately become so marked that property that now sells for $35 per square foot sold at $25 just one year ago.)

A private study of the area’s development was financed by the city’s Planning Commission and the Lincoln Square Community Council, and the report stated that while it is sound government policy to encourage private capital to renew areas that will attract white residents, “the local residents feel threatened by such renewal.

“New construction usually means displacement of the poor, the elderly, the Negro and the Puerto Rican, including many who are lifelong residents. The spectre is of a district and not a neighborhood; impacted with non-local institutions; filled with large buildings of high-income, childless occupants; congested and hazardous streets, and of an impersonal and over-whelming environment.

“For many West Siders, the East Side can’t be mentioned without comments about its ‘sterility’ and lack of community life.”

“Thus the basic issue facing Lincoln Square and the city is how to retain both the neighborhood’s social and physical diversity and simultaneously accommodate and control necessary new growth.”

Unguided growth could produce, according to some planners, a string of massive institutional buildings like schools, hospitals and cultural centers along Broadway from Lincoln Center to Columbia University. “It might seem far-fetched at first,” one planner said, “but remember that Fordham’s new building in Lincoln Center must be multiplied 40 times to accommodate the projected student population in 30 years. Columbia to the north has similar problems, and with the natural tendency of institutions to build near each other, Broadway could someday be lined with a wall of essentially alien and insular communities—because that’s just what such institutions really are.”

The Lincoln Square Special Zoning District was created, therefore, and empowered by the legislature to save threatened residential blocks, guide commercial development in the area and provide builders, through a complicated set of zoning concessions that could prove extremely profitable, with a realistic justification for incorporating arcades, galleries, pedestrian promenades and sheltered plazas for the public in the over-all design of their buildings. According to Richard Weinstein, director of the City Planning Department’s Manhattan office, the Lincoln Square Zoning District is “the most sophisticated effort by a municipality to build significant public works with private money.”

With the assistance of Hart, Krivatsy and Stubee, a New York- and San Francisco-based team of brilliant young planning consultants, the special zoning has the potential of turning the West Side into one of the most beautiful parts of the city rather than a jumbled horror. “It’s very simple, really,” one zoning expert said. “By allowing a builder to add five more stories to his office building, or so many more thousand feet of floor space, or any of a whole series of concessions or bonuses which will make this building more profitable, he agrees to incorporate a promenade or an underground subway entrance with open space and light.

Among other developments seen for the West Side as a result of the special zoning regulations is the leasing of air rights over the 90-acre Penn Central railroad yards between 59th and 72nd Street and West End Avenue and the river. There are already plans for extending Riverside Park south to 59th Street to meet the three new luxury piers planned for that location. The Department of Parks has allocated money for the rehabilitation of 13 blocks of the Broadway mall as the first stage in upgrading Broadway. There are plans to close West 63rd Street to traffic and provide a mall from Lincoln Center to Central Park. The local groups are currently engaged in a bitter struggle with a private developer who wants to erect a 42-story luxury apartment at that location with a 500-car garage entrance directly across the street from a school.

A less pretentious, though in many ways even more imaginative, piece of West Side design is a small playground at Central Park West and 67th Street. The creation of Richard Dottner, the playground bears no similarity whatever to the Robert Moses don’t-swing-on-the-swings approach to playgrounds. Dottner built a two-level tree house around the trunk of an old tree and a 10-foot-high pyramid of railroad ties with a slide on one side wide enough for three youngsters and lots of ways to get off without losing face if the slide proves too steep. There are smaller pyramids filled with ladders and tunnels and slides. There is a storyteller-in-residence, and tacked to the playground fence are drawings and notes for the band of mothers who organize the ad hoc activities and guard their young.

“Before the Adventure Playground and the new vacant-lot playgrounds,” one local woman said, “the playgrounds in the area were awful. They were like prisons. They were all painted those dull greens and grays. I’d watch bright kids go into those swing-and-seesaw horrors and be bored to death.

“Soon after we started over here, however, I began to notice that the playgrounds were getting more and more crowded. The Adventure Playground, for instance, is really much too crowded at this point, and one of the reasons, you might be interested to know, is that a lot of East Side mothers are sending their kids over here to play.”

For many West Siders, like this aggressive young mother, the scent of pride is in the air. The East Side can hardly be mentioned without gratuitous comments about its “sterility,” its part-time residents (“they’re off in Geneva or Palm Beach most of the year”) and its resultant lack of community life.

“We lived over there before we moved,” the woman continued, “and when I took my kids to the park I was surrounded by nannies who looked at me as though I had a disease.

“We used to worry about all that stuff. You know, about the West Side being a state of mind, a way of life. My husband and I were stupid enough to worry about it so long that when we finally moved we paid $65,000 for a house we could have gotten for $18,000 five years ago. As far as I’m concerned, if you have a family and want to live in New York, it can only be done on this side of town. If you’re a career girl on bennies or a millionaire, the East Side’s home.”

To the area’s new resident activists, builders and city planners, the next West Side Story will be very different from the last. It has been, after all, 12 years since Leonard Bernstein wrote his gang-war musical and six years since the Vivian Beaumont Theatre replaced the West 64th Street tenements in which the play was set. That huge, sprawling, alternate-side-of-the-street society filled with shabby, low-rent housing and Oscar Lewis runaways is changing fast. “In five years,” one city planner said, “the only dumpy little shoppingbag ladies you’ll be able to find on the West Side will be stuffed and behind glass at the Museum of Natural History.”